I Find an Answer

We spent most of Saturday on the beach, swimming and playing around the boats and rock pools. In the afternoon my father walked along the coast with us to a lonely bay with white sand, where we looked for shells. I lay on the hot rocks and gazed into a pool like a miniature garden, with starfish, sea anemones, waving seaweeds, and tiny snails. I thought God must be a wonderful Creator to design such fragile beauty.

On Sunday we were having breakfast on our little patio, and the church bells were pealing out all over the town.

“Daddy,” I said firmly, “it's Sunday. Can I go to church like I do at home, and can I have a Bible to read?”

“I'm afraid I haven't got a Bible,” he said, “and since the churches in this town are all in Spanish, you wouldn't understand a word. Besides, they're not the kind of churches you've been used to.” He hesitated, as though he had more to say.

“Lucy,” he said at last, “why do you want to go to church? Does it mean anything to you at all? Do you go just because Gran tells you to? And do you read your Bible because it helps you or makes a difference to you? Or is it because you've been taught it's the right thing to do? Think it out and give me an answer. I really want to know. I don't like people who just pretend to be good or religious, and I don't want you to be one.”

I stared at him. I knew that none of the answers I could have given would satisfy him.

Lola and the children had gone to Mass in their best Sunday clothes, and the bells had stopped ringing. My father seemed more breathless than usual, and I hadn't the heart to ask him to come to the beach, so I sat beside him and wrote to Gran. Then I went down to the beach to look for shells by myself.

We were invited to dinner at the inn kitchen where we gathered around the table under sides of bacon and bunches of herbs and garlic hanging from the ceiling. Several bottles of wine were drunk and everyone became very happy and talkative. By the time we finished, it was late in the afternoon. Sunday was hurrying past, and I had still found no answer to Dad's question, nor any solution to my problem. For the first time I felt really lonely, and I thought of the old woman up the hill. I would go to visit her.

“Daddy,” I said, “I'm going to visit an old woman who lives on the other side of those eucalyptus trees. Can I take one of our peaches to her?”

“Take her two, Lucy.” He picked out the best and put them in a bag. “I'm glad you're making friends around here. You'll be chattering Spanish in no time, and I want you to love Spain. Don't go far, and come back before sunset.”

I slipped out quietly in case the other children saw me and wanted to come with me. I liked being with them, and I loved Rosita, my amiga, but now I wanted to be alone. It was still very hot, and I was glad for the shade of the eucalyptus trees. I liked their smell, the rustle of their dry leaves, and the whirring sound of the cicadas that made such a noise but that I could never see.

I walked slowly, thinking about Dad's question. What did church really mean to me? I thought of Sunday at home—putting on my best clothes, singing the hymns as loudly as I could, making up stories and poems during the sermon and hoping it wouldn't be too long, Grandpa falling asleep and Gran looking at us out of the corner of her eye, the prospect of a roast for Sunday dinner, my favorite pudding, and a free afternoon. Did church really mean anything more? I couldn't honestly say that it did, except very occasionally, like on Good Friday or Easter Day.

When I came to the house at the edge of the vineyards, there was no one to be seen. They were probably all still having a siesta and would come to life at sundown. So I knocked rather timidly at the old woman's door, and it was opened immediately by her little granddaughter. I peeped in, and there was my friend sitting at the table, her glasses on her nose, reading her Bible.

Why? What did it mean to her? Something, I was sure, judging from the look on her face. Since I couldn't speak to her, I did a strange thing. I went straight up to her and put the peaches on the table. Then I pointed to the Book and repeated the word that the children at the inn said about a hundred times a day: “Por que?” Why?

She did not seem at all surprised. She just pointed to a word on the page, and I squatted down beside her to look. The word was Jesus. It was the same in English as it was in Spanish. She spelled, pointed upward, then said very simply, “Jesus es mi Amigo.”

Amigo—it was the word Rosita used when we walked down the road arm in arm and she introduced me to everybody. Amiga, because I was a girl, but the same word. “Jesus is my Friend.”—not someone in history, but near and alive. I suddenly realized as I gazed at the page that praying and Bible reading and churchgoing were no longer three roads leading into the mist. The mist was clearing, and the roads were leading to a bright center. They led to Jesus—not a person in a storybook who died hundreds of years ago, but Someone who was alive now. He was the old woman's Friend, and I saw no reason why He shouldn't be my Friend too. For I suddenly knew that this was what I had been looking for all the time … not words, or rules, but a Person.

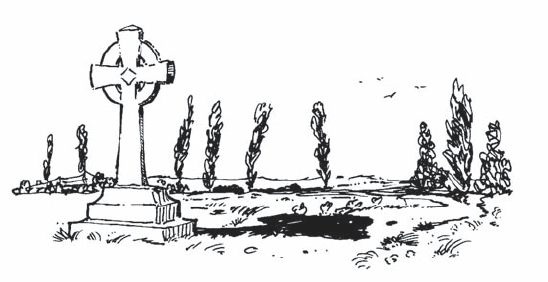

The discovery was so great that I wanted to stay near this old woman whose Friend was Jesus, but we couldn't find any more words in common. Somehow I found myself on the dirt track that led to the farm, and there in front of me was the stone cross, which now seemed very important because it was on a cross that my Friend Jesus had died.

“Thank You,” I said, looking up at it, and at that moment I knew what saying my prayers really meant. It was just talking to my Friend, saying thank You, telling Him things and knowing that He was listening. It was too hot to stay long near the cross, but I sat under an olive tree nearby and stared across at it and started to talk to Him. I asked Him never to let me tell lies again, and I asked Him to show me how to choose, and I asked Him to make my grandparents and my father like each other so that we could all be one family.

The stone cross cast a long shadow along the path, and in my imagination the dirt track, lit up in the mellow light of the sunset, seemed like the beginning of a new life. I could set out on this bright road with all my tangled, troubled past behind me and Jesus, my Friend, beside me. I loved Him and longed for a Bible, because it no longer seemed like a dull, old history book, but a Book where I could learn more about my Friend.

The sun disappeared as I came out through the eucalyptus wood, and the sky was streaked with crimson. Lights were coming on in the shops, and the town was waking up. My father was sitting at a table on the pavement having a drink. I sat down beside him, happy, hot, and thirsty, and he ordered me a lemonade.

“Daddy,” I said eagerly, “you know what you asked me?”

“When, Lucy?”

“This morning—about church and the Bible.”

“Oh yes. Have you thought about it?”

“Yes, and I know the answer. The old woman told me.”

“What? In Spanish?”

“Yes, and I understood. I know now!”

“Really? Do tell me!”

“I want to go to church and I want to read my Bible because … because Jesus is my Friend.”

I expected him to smile that twisty smile of his, but he didn't. He just looked at me, and then replied very gently, “In that case, Lucy, I'll get hold of a Bible for you as soon as I can, and if there's such a thing here, and if you're happy to go on your own, I'll find an English church service for you.”