CHAPTER FIVE

Why I Wasn’t at Woodstock

Yesterday, Margo slept until two, got up and ate a bit of breakfast, then went back to bed. When I tried to rouse her at dinnertime, she shook her head.

“I think I’m dying,” she said before she drifted back to sleep.

But today, when the home health nurse arrives, Margo is up, bright and happy, taking in an episode of Breaking Bad, which she likes to watch with the subtitles turned on so she can do the dialogue along with Walter White/Heisenberg and Jesse Pinkman.

“If you believe that there is hell, I don’t know if you are into that. But we’re already pretty much going there, right? Well, I’m not going to lie down until I get there,” says Margo Heisenberg, and Margo Pinkman retorts, “What, just because I don’t want to cook meth anymore, I’m lying down?”

“Sorry for asking you to make an extra trip,” I tell the nurse. “When I called last night, she seemed very low.”

She smiles an understanding smile. “It’s like a roller coaster. Only you’re not on the ride.”

But I do feel like I’m on the ride.

“No one else is gonna get killed,” Margo tells the television. “Yeah, you keep saying that, and it’s bullshit every time.”

“Hello, Margo.” The nurse gives her a warm hug. “Shall we check your vitals?”

“Oh! Aren’t you wonderful to think of that?” Margo hugs her back. “That would be a terrific thing for us all to participate in.”

“All right. You first, then Swoosie.”

“You know my daughter? Swoosie Kurtz? She’s beloved. Or beloved. That would be another way to state the fact.”

The nurse takes Margo’s temperature, pulse and blood pressure, then takes mine, and then she does Perry, who has arrived with his dog Boo.

Margo grasps my hand and says, “This is your husband?”

“Almost,” says Perry.

“Margo, I don’t have a husband,” I remind her.

“Oh, no . . . darling. Tell me he hasn’t died.”

“No, I’ve never been married.” But then I see that her eyes are on the door down the hall, and I wonder if perhaps she means Frankie.

“Interesting,” she says after a moment. “I thought maybe you’d like someone in your area.”

Twelve off-color comebacks cross my mind. Things that Joyce, my character on Mike & Molly, would say without hesitation.

There’s been a lot of speculation about my romantic life over the years, why I’ve never been married, and whether my sexual orientation is straight, gay or ambidextrous. In the minds of many, if a woman never marries, it means she was never wanted, or (if she was wanted but failed to appreciate it) she must be a lesbian. I was an attractive young woman, eminently credible as a suburban wife and mother onstage and on-screen, and I aged without much need for surgery—cosmetic or catastrophic. These days, I am a woman of a certain age who’s kept herself fit and healthy and turns out a good pony show on the red carpet. I have good teeth and some money.

Well, then, people wonder, what is wrong with her?

I know it would be terrific for the sales of this book if I were to come out as a lesbian in the next paragraph, so right here on this ten-meter platform of tell-all truth, I’d like to say that I am . . .

Sorry. I got nuthin’.

We all know there is no such thing as a tell-all, nor should there be, but the unfortunate whole-wheat truth here is: I am both straight and narrow. I haven’t been a nun, but I am almost that married to my work. And I tend to dress in black most of the time. (That’s what theatre people do; you won’t find a community that wears more black and watches less television unless your car breaks down in Amish country.)

I always knew that I did not want to have children and never felt compelled to analyze or articulate why. Getting married wasn’t something I actively did not want, but I was never fully available for it at any given moment. I was never fully available for anything that took me away from my work, and suddenly forty years went by, and I just sort of . . . forgot to get married. It seems to me that if one has to set a reminder on the calendar (“Pick up dry cleaning and get married before menopause!”), one is doing a disservice to the person being penciled in.

My mother had a choice, and she chose to make marriage and motherhood her life’s work. I followed in the career-consumed footsteps of my father. Candidly, it might have made things easier if I had been born a lesbian, because what I really needed was a wife like Margo. Do you have any idea the percentage of my income that has gone to the agents, managers, housekeeping staff, shrinks and stylists who do for me what Margo did for Frankie? I’m not complaining. Just reporting. It’s significant. Between my work schedule, my OCD/hermetic tendencies, the towering memory of my father and my ongoing devotion to my mother, I think I’d be a high-maintenance wife by conventional standards. I have periodically been an excellent girlfriend, however. I’ve been told by the best that I do a hell of a second date.

One of the many things I love about Margo is that she never questioned my choices, never pressured me to accommodate a man or the rote expectations of society. She has always known me so well; she must have realized early on that I was a better candidate for prima ballerina than I was for suburban housewife. She never pined for a grandchild or hinted that my biological clock was ticking. Or that it wasn’t ticking loudly enough.

My going out into the world as an artist required no act of rebellion; I never felt I had anything to rebel against. But I did go out into the world, God knows. I did go out into the world.

I graduated high school with honors onstage at the Hollywood Bowl and went off to USC, still a nonsmoking Sandra Dee prototype with a full-ride scholarship in place and my virginity intact. Time magazine ran a lovely photo of me striding across campus flanked by Margo and Frankie. The accompanying article, a few column inches under a piece about Marilyn Monroe’s will being filed for probate and just to the left of a breezy account of Jackie Kennedy’s recent yachting adventure in Capri, is mostly about the historic significance of the Swoose, how the Swoose got its name, and I subsequently got mine. The photo is captioned: “SWOOSIE & PARENTS: At 17, all swan.”

In that moment, I was an apt poster girl for women of my generation, suspended in glossy black and white between Marilyn’s cautionary tale and Jackie’s fairy tale. Not long after the photo was taken, I met Josh White, and he transformed my life.

Omaha, 1938

Before another Christmas came round, I had gone miles off our course. The weather aloft was too much for me, I’d come out of it, down, and goodbye forever to flying. The rough weather consisted of friendly voices, queerly misguided friendly voices saying over and over, “Margo, you are wrong to spend all your youth waiting for someone who isn’t ever going to do anything about it.”

“Margo, you’re not being fair to yourself—you owe yourself some fun, you should be dating some of these boys. You know, you’re only young once.”

“Margo, he’ll always put work, flying, everything ahead of you. Now, there is this young man, Bill, you know, he would always be so wonderful to you, and he would give you such security.”

I’d known how to fly above that weather for nearly four years; but somehow, now, it began to be too much. You see, the time was nearing June of 1938, when Frank would become a second lieutenant, a June that would be just perfect for getting married in, and why didn’t he ever speak of these things in letters?

Well, there came a letter, and it did have a June thought in it, an absolutely unlooked-for June proposal.

“I am going to request permission from the War Department for some special study when I graduate this June. I believe I can swing it. Of course, darling, there is the one bad point—it will keep us separated another year. But I know you won’t mind—it will be a wonderful foundation.”

It was enough to wither a girl’s heart.

For a while I dated the boys, but in the midst of the friendly voices, all so approving now, there was a kind of silence making me feel jumpy. Like when the hum of a motor has suddenly died, and you keep waiting for it to come on again.

I thought a typewriter might fill up this silence, and so I got a secretary job, but there were loopholes for silence even there. Then I thought the noisiest job in the world would be a kindergarten. I went back to college to study to be a teacher, and I went around in sober dresses and flat-heeled shoes, and thought about nothing except child psychology, for months.

Home for Christmas, and there was a warmth and coziness about the fireplace, and the family all around, and a tree with presents. It was a nice outside warmth, and that was all. I didn’t care—I didn’t care about anything.

On a cold afternoon I came home from a cocktail party, chilled through in spite of all the gaiety. And as I walked in the door, there in front of me was a burning red bouquet of three dozen roses, the kind Fred Astaire sends in the movies, and someone was handing me a card—“I’ll be with you this evening”—and I didn’t understand this card, but there was a little pinprick against my heart, and perhaps I did feel a little warmth beginning, inside.

I thought, well, it is a holiday, and why don’t I make myself look a little brighter? The sleigh and reindeer—that was an army bomber, and the “gift” which arrived with, oh, such a jingle-bell ring of the doorbell was a tall, handsome Air Corps lieutenant—how the silver wings shone!—whom I’d never seen before, and with whom I’d been at home forever.

It was nice to sit by the fire and feel really warm. After a while, Frank was looking into the fire pretty seriously, and saying: “I’ve tried all the ways I knew, to tell you, Margo, I love you, and if you don’t believe it now—just ask my Commanding Officer. He said, ‘For God’s sake, Kurtz, take a plane, and go back to Omaha and marry that girl so I can get some work out of you!’”

Except in cases like Frankie and Margo—those rare instances where one’s First Great Love actually sticks—I think the function of a first great love is to introduce us to ourselves, and then initiate us into the world of the brokenhearted. We go into it not even suspecting what we’re capable of and come out of it amazed at what we’ve already done. A first great love, if you’re lucky, follows the Bonnie and Clyde triptych: mutual cahoots-inducing sexual chemistry, a long spree of behavior that feels like getting away with murder, and a blaze-of-glory finish that leaves you both full of holes on the roadside. Josh White and I enjoyed all but the last of these, and two out of three, as they say, ain’t bad.

Josh came to the cinema department at USC after studying theatre and design at Carnegie Tech (Carnegie Mellon, in modern parlance). He was a native New Yorker with a very New York sensibility about theatre. He was wryly adorable with his Woody Allen glasses and Jewish idioms. He wasn’t much taller than me but was far more worldly and had a very urbane fashion sense. He didn’t mince words about my airy hair and cashmere twinsets.

“You’re very blond,” he said bluntly. “You might want to tone that down.”

One of my strengths as an actor, if I do say so myself, is that I appreciate good direction. I developed a thick skin and learned the difference between an ad hominem tear-down and a genuinely constructive critique. This was the best kind of criticism: the kind that confirms what you already know and challenges you to be true to yourself. When I tell people that Josh helped me shop for clothes, decorated my apartment, hooked me up with a haircut at Vidal Sassoon and bought me a black Rudi Gernreich swimsuit, they assume he was gay and I was deluding myself, but in fact, he was just one of the early 1960s avant-garde. He was interested in cutting edge art of all kinds, and the work of both Vidal Sassoon and Rudi Gernreich (who changed the world by inventing the monokini) certainly fell under that heading.

Margo enjoyed Josh’s quick wit and bookish brilliance and respected him as a curator of chic. They had in common a fabulous fashion sense. Frankie, on the other hand, had very little use for Josh and, in fact, persisted in calling him “Jeff” throughout the six years that we were an item. Josh (in Frankie’s mind) had never had to work for anything. Strike one. Josh was a political liberal. Strike two. Strike three always seemed to be lurking on the tip of someone’s tongue, which made it stressful to have the two of them in the same room.

Basically, they came from two different universes. Josh’s family was wealthy, and his father (a television producer) fully supported Josh’s varied artistic endeavors as worthwhile occupation. Frankie was a self-made man who perceived Josh as silver-spoon-fed, and while Frankie always backed me in my own artistic endeavors, he was profoundly uncomfortable with the fact that Josh took me on expensive vacations and bought me things, which might give the impression we were “shacking up,” and I was one tap shoe away from being a kept woman. I, of course, went all West Side Story—“But I love him! Nothing else should matter!”—which did nothing to ease the tension. It was the first of the very few times in my life when Frankie and I were at loggerheads over anything.

I convinced myself that my parents didn’t know that when I went to New York with Josh, I gave it up at the Waldorf (which is really not a bad spot to forfeit one’s virtue), because back then, the assumption was that a nice girl was a virgin until she got married. I certainly assumed Margo was a virgin until she got married. I’m not sure why we never confided in each other about this detail of our lives. All Margo told me about their wedding night was that she and Frankie checked into their hotel and realized they didn’t have a key for their suitcase, so Frankie had to call down and ask the front desk to please send a bellman to the honeymoon suite with a hammer and screwdriver.

(Get out of my head with the double entendres, Joyce. I mean it.)

They asked the elderly bellman to hang out with them and have a glass or two of champagne; so apparently, they weren’t exactly in a frenzy to be alone. In her book, Margo was appropriately circumspect about her sexuality, but she was candid about her longing when Frankie was away and her attempts to seduce him when he was too exhausted to seduce her. To me, in personal conversations, she added the detail that in their early months together, she lay in bed beside him, wide-eyed with fear she’d pass gas.

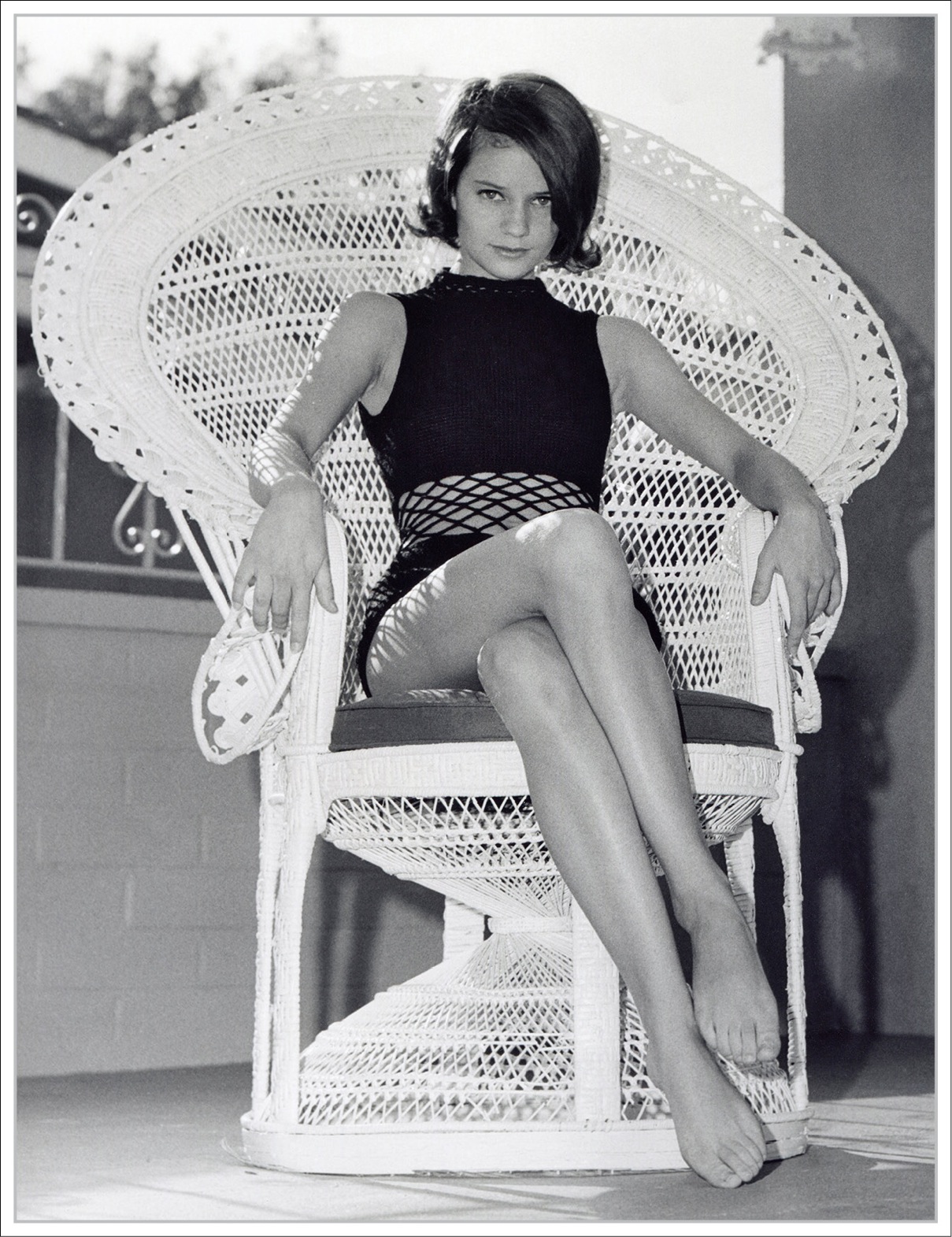

Josh wanted to photograph me in the black Gernreich monokini; I was as wisp-thin as a French model and a lot more pleasant to be around. He staged the photos in the backyard at my parents’ home in Toluca Lake, but from the look on my face, you’d think I was in Biarritz. There’s one where I’m sitting in a white rattan peacock chair with my legs crossed and toes pointed exactly the way they were in that photo of the four-year-old me on a white bench at the aquacade—except the sunny look on my face in that photo says “lucky me.” The sultry look on my face in Josh’s photo says “lucky you.” His presence is as evident as a tourist’s thumb in a snapshot of the Grand Canyon. If Margo didn’t know what was up when I got back from the Waldorf, she had to have known it when she saw that photo.

“If you want to do real theatre, Swoosie, you have to be in New York,” Josh told me, and here again, it was nothing I didn’t already know, but I had a full-ride scholarship at USC, where my parents were celebrated alumni. The suggestion that I might be better off on the other side of the country wasn’t well received. Josh helped me set up an audition at Carnegie Tech and went with me to New York. I was accepted, but I couldn’t feel any more enthusiasm about going there than I felt about staying in L.A.

Josh wanted to photograph me in the black Gernreich monokini; I was as wisp-thin as a French model and a lot more pleasant to be around.

JOSHUA WHITE

It’s funny that Margo and I both came to a turning point after two years at USC. We both left to be with our one true love. She left to follow Frankie; I went to the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Arts.

“Swoose, why not finish your degree here first?” Frankie pleaded. “You’ve got two years in, a full scholarship. This doesn’t make good sense.”

But it made perfect sense to me. (At least as much sense as it made for Margo to ignore all those well-meaning voices telling her she was crazy for waiting six years to marry someone who was likely to fly away and get himself killed.) But as the time of LAMDA’s Los Angeles auditions approached, I got very nervous—nauseous nervous, which was very unlike me—and I think Frankie saw that this was extremely important to me. As a friend says about her daughter’s tattoos, “It’s a part of her, therefore I love it.” Frankie turned that same sort of corner, seeing that this was the path from which I would not be swayed. He and Margo let me know they were ready to help me do what I needed to do.

Facing me at the audition was a tall, gaunt English actor, Alan Napier, who’d been onstage with Sir John Gielgud in the Oxford Players and on film with Orson Welles in Macbeth and would later play Alfred, Batman’s stalwart butler, on television. He was lovely, very encouraging, and I had a good feeling even before I got the letter. When I was accepted, it was like a dream. Or maybe like waking from a dream into real life.

My friend Dolly and I came up with a plan to see Europe on the cheap before school started. We bummed hither and yon, stayed in hostels and drank too much. Then Josh flew over to help me set up housekeeping, and I rented a pretty little flat where the lovely landlady looked just like Peggy Ashcroft.

“No wild parties,” she said curtly as I was moving in. “And of course, no blacks.”

I decided to move down the street to a place on Earl’s Court Road that was half the size and not as pretty, but also much cheaper and not as bum-stuffed (as they say). I was much happier there. Margo and Frankie never harped on it, but I was very conscious about spending their money. They were paying my tuition, and sometimes Margo would send me $20 in a letter, knowing I wouldn’t ask for it and could really enjoy nonessentials only if I earned them for myself.

Wherever I go in my career, I’ll probably never experience a paycheck that made me feel as rich as the $100 or so that I’d received for my blink-and-you’ll-miss-it on The Donna Reed Show. I just wasn’t good at spending anyone else’s money after that. I’m not extravagant by nature, and I liked being organized about my home and school budgets. My new apartment had a grand old claw-foot bathtub, but it didn’t have automatic hot water. You had to put in several two-shilling pieces and hope for the best, always emotionally prepared to shampoo under a lukewarm tap and rinse with ice cold. A few hours of power also required an infusion of two-shilling pieces, so I’d often wake up frozen to the bone because my electric blanket had gone cold, or I’d have to go off to class with only one side of my hair done.

All that aside, I was in my element and loving every day. The American Course was only one year, so I lobbied to take the English Full Course, which was two years. I’d left USC without graduating, but I hadn’t traveled all the way to London to go to school with Americans. I was elated when it was decided I’d be allowed to do the two-year, deep-dive into all the nuances of elocution, the grammatical structure of Shakespeare, all the guts and bones and feathers of the craft.

Michael Macowan was the artistic director at LAMDA back then, and he reminded me a lot of Mr. Ingle with his pugnacious energy and appetite for characters. One small exercise that made a strong impression on me early on: Working on Chekhov’s Cherry Orchard, one of the actresses was required to slap someone, but each time we came to that moment, she couldn’t bring herself to do more than sort of apologetically smack the guy.

“Look, just slap your own hand,” Macowan told her. “Give it all you’ve got.”

She tepidly clapped one hand to the other.

“Commit to the physical act,” he urged. “Go there. See what fuels it.”

She raised her left hand to the level of the actor’s face and slapped it hard. I could see the connection in her eyes, like lights turning on in an attic, and that spark of electricity arced for an instant with the actor facing her. She slapped him, and he felt it—not just physically, but truly, emotionally, viscerally. Not because it was a real slap, but because it was real theatre. The physical act did take her there, and she took her cast mate with her.

“Right then,” said Macowan. “Because we can’t wait around for you to feel it eight shows a week, can we?”

This simple truth has stayed with me throughout my career. Years later, during a table read for the movie A Shock to the System with Sir Michael Caine, a young castmate (who hadn’t yet learned that a hole is to dig and a table read is to read) kept pausing to ask endless questions about motivation and subtext. Finally, gently and gentlemanly, Michael said, “Tell you what, luv, it will all be revealed at the premiere.”

With all due respect to the Stanislavski purists, there are times when we’re onstage, and someone’s Uncle Horace is hacking up a lung in the second row, or a fire truck is screaming down the alley, or the person you’re in bed with smells like a bag of old hams, and you just don’t feel what your character is supposed to be feeling. Sometimes you feel like an actor who has sprained her ankle or lost her lover or heard some hideously funny remark made backstage.

Really, this is applicable to daily life as well. Isn’t so much of what we do based on a willingness to commit our presence to a given moment? The most challenging role I’ve ever played is the Unflappable Daughter who remains calm in any given crisis, even as my stomach crumbles into the rubble of suppressed panic. I can’t make things all right for Margo, and I can’t feel fine and philosophical about her decline; I can only commit to be here with her, and on good days, my willingness to do that creates an arc of energy. The lights go on in Margo’s attic, her joy reflects mine, and my joy becomes genuine.

To this day, so much of what I learned at LAMDA enters into my work (not to mention my daily workout), because it simply made sense to me. We were taught to engage both the physical center of the body, near the tailbone, and the emotional core of the body, the solar plexus. We stretched. We strengthened. We tightened down and loosened up every muscle including our vocal cords. We immersed ourselves in words, learning to deconstruct sentences in search of a playwright’s nuanced meaning, changing dialects as easily as we could change a hat.

For me, there was the added luxury of the British dialects that surrounded me. I was endlessly fascinated and entertained by the idioms and classically British understatement. My singing teacher, for example, used to tell the class, “That didn’t exactly ravish me.” (So many uses for that one!) One Friday evening, I was standing on the platform in the Earl’s Court tube station with my classmate Maureen Lipman, who became a very successful actress in the West End and on British telly. We had our heads together over a newspaper, deciding which movie to see, when a phone rang in a nearby phone booth. We looked at each other. Shrugged an unspoken what the hell? and Maureen stepped inside, picked up the phone and said in her inimitable British accent, “Earl’s Court Tube Station, may I help you?”

A brazen voice inquired if she’d like to suck his you know what.

“No, thanks,” she said. “I’ve just put one out.”

How could I not love such people?

My first year in London, Josh came over to see me during Christmas break, and we went skiing with his parents, who were welcoming and warm. They had a house in Klosters, Switzerland. I had not been skiing before that, and I have not been skiing since, but I wasn’t about to be the one left behind on the bunny hill.

The second year, I went with him to the Venice Film Festival, where his short film, The Sunflower, was being featured. We stayed at the Lido Excelsior Hotel, and he photographed me in my bikini on the grand staircase after I won third place in the Excelsior Guest Beauty Contest.

Josh and me in Europe, probably 1964 or so. Dig those Nehrus!

JOSHUA WHITE

We didn’t talk about anything that had happened in the past or would happen in the future. We were in love when we were together, and when we weren’t together, I was in love with whatever play I was in. I dated here and there, but wasn’t particularly bowled over by the Brits when it came to the romance department. I graduated from LAMDA with a general idea of who I was as a human being, in command of all that I had learned, and in awe of all that I had yet to learn.

“You need to come to New York,” Josh told me again, but he didn’t need to. I was already scoping out auditions and querying agents. While I looked for an apartment, it made sense for me to stay with Josh at his place in a great old brownstone owned by his father. So we were together again, together meaning together, as far as I knew, and that didn’t change when I moved into my own place just two blocks away. It was perfect. Josh was at 33 East 63rd, and I was at 33 East 61st, which meant we could see each other every day, but lights out would always find me comfortably tucked in with Javitz and whatever script I was studying.

New York had changed since I was a little girl swooning at the stage door. John F. Kennedy was dead; John Lennon was alive. Josh had started his strange and wonderful Joshua Light Show, combining all his strange and wonderful sensibilities—theatre, film, art, music, magic tricks, puppetry. Josh and his merry band called it “arcane arts” and “mixing the Druid fluid.” He burned and melted things in pots and pans, dribbled ink down a broken windowpane. He shot footage of my eyeball and projected it fifteen feet tall. The goal was to suck audiences and performers into one psychedelic surreality, a pitch-perfect chaos.

After three weeks at the Anderson Yiddish Theater with Moby Grape, Procul Harum, B. B. King and Big Brother and the Holding Company, the Joshua Light Show moved to the Fillmore East as resident artists, producing four culture-shifting shows a week for more than two years. A 1969 New York Times article marveled at their “Mondrianesque checkerboards, strawberry fields, orchards of lime, antique jewels, galaxies of light over pure black void and, often, abstract, erotic, totally absorbing shapes and colors for the joy of it.”

That article was headlined “You Don’t Have to Be High”—and believe it or not, we weren’t. I was usually doing a workshop or show off-off-Broadway. Sometimes as far off as Cincinnati. I did a lot of schlepping around to regional theaters during those years. But during the happy stretches of being home in New York, most weekend evenings, I’d arrive in Josh’s scaffolded kingdom backstage at the Fillmore East at half past eleven. The crowded space was populated with roadies, bandmates and icons: Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane, The Byrds, Grateful Dead, The Doors. The air was an asthma-inducing mélange of dope smoke, dust, mildew from the old seats, and fumes from the overheating airplane headlights and Franken-rigged slide projectors. While most people were trick-or-treating for whiskey and acid blotters, Josh and I sat on barstools near the control board, a couple of squares sharing a bottle of Coke and a box of onion crackers. Art was everything in our hardworking but adequately funded la vie bohème existence. We were utterly in love with each other and with our work.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, a marvelous play based on the novel by Muriel Spark, opened in London just before I left and quickly migrated to New York. I was cast as Monica in a summer tour. Our Miss Jean was played by Betsy Palmer, and we followed her from the Poconos to the Jersey Shore, staying in miserable digs that could hardly even be called hotels or even motels—these were summer camp shacks calling themselves cottages, often too ramshackle for real guests but plenty fine for us.

Every night, Miss Jean Brodie instructed her Little Girls: “Miss Mackay retains a picture of the former Prime Minister on the wall because she believes in the slogan, ‘Safety First.’ But Safety does not come first! Goodness, Truth and Beauty come first! . . . Benito Mussolini is a man of action, he has made Capri a sanctuary for birds. Thousands of birds live and sing today that might well have ended their careers on a piece of toast.”

And that—long story short—is why I was not at Woodstock with Josh, who was in his element, projecting his spectacular vision. I suppose I missed Woodstock for the same reason I forgot to get married: I had a show to do, and I was so happy doing it, truly, I never gave much thought to anything I might be missing. And now that I have given it some thought, I can honestly say, I don’t regret a thing. It’s fairly revelatory that in our six years together, Josh and I never once discussed the possibility of getting married. I saw it as one or the other: have my life absorbed by my work or have my life absorbed by another person. Those were the two role models that had been set before me. If I’d ever met someone I couldn’t resist marrying, I might well have ended my own career on a piece of toast.

I returned from the tour, exhausted but elated. I was so happy to wake up in Josh’s rumpled bed. But when I went into the bathroom, I discovered a cache of pink plastic rollers. The kind that gave a girl that purposefully messy Brigitte Bardot coif—a stunningly slutty version of Sandra Dee.

Blah blah confrontation, blah blah tears, blah blah I love you, but she’s easier to be around because you’re so blah blah blah. What does any of that ever mean? Especially when you’re in your twenties, and you think you know what complicated is, but in truth, you haven’t a clue. Sob story short, Josh broke up with me. Not to be with roller girl. Just to not be with me. All in the game, I guess. Many a tear has to fall and all that rot.

1968: Jimi Hendrix onstage with my all-seeing eyeball projected by the Joshua Light Show at the Fillmore East.

THE JOSHUA LIGHT SHOW

I continued working in another off-off-Broadway show. Josh called and called, but I wouldn’t answer. I was grateful to lose myself in eight shows a week. Standing in the dark, waiting for the time the stage manager calls places, I could feel my splintered heart beating. By curtain call, it even felt like love.

About a year later, while I was doing The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds, I ran into Josh one night, and he looked good. He was still everything I had fallen in love with, and there was a brief panicky moment when I thought he wanted to get back together, but as minutes dragged by, we just made a little pile of small talk between us, the way you make a little pile of crumbs and dog hair on the kitchen floor before you sweep it into a dust pan or whisk it out the back door.

“What are they paying you?” he asked.

“Sixty-five a week before taxes,” I said.

To his credit, he did not point out that I would have gotten more on unemployment. I didn’t care. The truth is, most of us weren’t even thinking beyond the next time the stage manager calls places. Any of us would have done that gem of a show for free if we’d been asked.

That’s how actors are hard-wired. “It’s worth it,” we tell ourselves, “You never know. Someone might see me. It might lead to something else.” I still tell myself that every time I do a table read in exchange for a swag bag or an animation voiceover just to run it up the flagpole of an interesting producer. As grateful as I am for all the opportunities that have come my way, I’m not sure I’ll ever shake off the feeling that I’m waiting for my big break.

Last year, during a spring pilgrimage to New York, I had dinner with Josh. He looked like a gently aged Harry Potter with his black-rimmed glasses and undiminished desire to do magical things. We talked about Margo and how our lives are now. Josh had become estranged from his parents; his mother was in an assisted living situation since his father had died. His wife of thirty-five years had died as well, but he’d reconnected with a woman he knew in his Carnegie days and was planning to marry her. He seemed happy, and I was happy for him.

“I came across the negatives for those nude pictures,” he told me over dessert.

“Nude pictures?” I coughed. “Nude pictures of me?”

“Don’t you remember? I sent you the contact sheet decades ago.”

“Oh, my God . . . those. Right, right.”

I’d stuck the contact sheet in a drawer and tried to forget. Now I focused on my fork and plate so I wouldn’t see in his face what he’d forgotten or not.

“I’ll send the negatives,” he said. “Just so you know there’s no funny business.”

A few weeks later, he sent them, enclosing several other photographs as well, including one of Jimi Hendrix onstage in sweaty ecstasy beneath an enormous projection of my eyeball.

Josh had taken me to Woodstock after all.