CHAPTER NINE

Singing, Dancing and Schizophrenia

Omaha, 1941

So Christmas came. And on that day the headlines said: Manila Surrounded.

I knew, then, that there could be no call. So on Christmas day I drove around town and called on friends. I’d pop into a house here, and the family would all be together. They had just finished Christmas turkey and their belts were loosened. They sat around the tree while the children played with dolls. I knew each time I got inside one of these houses I shouldn’t have come. They were content before I arrived. Then the mother would nervously smoke cigarettes, and the father just sat there smoking his pipe. The girl would keep looking at her young husband, like she had something she shouldn’t have. And he was very uncomfortable.

It didn’t matter what we talked about, I could feel each one thinking, “She doesn’t even know if her husband is alive, but here she is on Christmas day so calm.”

I could know they were thinking this because not one could look at me straight in the eyes.

So I was an outcast everywhere I went on Christmas day. Finally I just went to my own room, our room with the K on the door. I spent the day writing Frank. And at night I drove past all the windows with the Christmas lights coming through in green and red shapes. We drove to the Post Office, alone, me and my letter. The corridors were very quiet tonight and dark.

Why is it that people are so uncomfortable with the thought of a woman who is, by choice or not, alone? It seems to waffle between suspicion and sympathy. Is she the witch or the widow? Or just waiting for Mr. Right? A solitary gentleman can be a confirmed old bachelor—or he can be the charmingly tardy Mr. Right—but a solitary woman must be Miss Havisham. I know the day is not far away when I’ll be living alone again, and I’m trying to be honest with myself about the period of adjustment, the painful reality of learning to live without Margo and our ad hoc family, but for many years, I’ve always been perfectly happy living by myself in New York, and I expect I will continue to be.

I love my New York apartment—the first place I’d purchased on my own. The building is an art deco monument, where you half expect to see Dorothy Parker step out of the ornate elevator. All the trims, tiles and inlays of the original design have been lovingly preserved or beautifully restored, an ongoing process that’s had its up and downs since Frankie found this place for me in 1982. Employing the wisdom of all his years in the real estate business, he marched me all over the Upper West Side, measuring square footage, testing pipes and grilling hapless superintendents. While Frankie skeptically clicked the feeble light switches in the dark hallway and pointed out cracks in the plaster, I opened the tall living room and bedroom windows, looking down on Central Park. I had no trouble envisioning my life here, and even though that original vision included Brent and Love, Sidney—neither of which remained when the plaster dust had settled—it wasn’t far from the life that in fact unfolded over the decades.

The neighborhood wasn’t as gentrified as it is now, and the apartment needed a lot of work, so the price was right. There wasn’t time to take a breath between Fifth of July and Love, Sidney. I was on set by day, trying to sort and pack the contents of the Diana Barrymore suicide chateau by night. Frankie stayed at the New York Athletic Club, where he still had privileges, and spent his days at my new place, barking orders at the housekeeper, measuring things, lecturing the workmen when they didn’t come up to his exacting standards, castigating the movers to be more careful with my things, even though I really had nothing of any great value. After a few days of this, I was ready to throttle him.

“Do you really have to make this so unpleasant, Frankie?”

“There’s a right way and a wrong way to get things done.”

“No there’s your way. Always. For everyone. Even if you have to shove it down our throats.”

I suppose we were ready to throttle each other, really. As I came into my own, I became more and more like him, and sometimes it seemed there weren’t enough cubic inches in the room for both of us. But he did get things done. With guilty relief, I’d show up every evening and see that another impossible task had been made possible: the plumbing, the wiring, the floors. He systematically transformed a crumbling mausoleum into a modern, well-kempt domicile where the kitchen cupboards were the correct height for my coffee cups, and the bathroom fixtures were the correct height for me.

Just as it all came together, we saw the announcement on Entertainment Tonight that Love, Sidney had been canceled. I remembered what a joyful surprise party it had been to see that Marigolds had won the Pulitzer. This was the evil twin of that moment. (It’s nice now that we have text messaging, which delivers unpleasant news like a surgical scalpel instead of a chainsaw.) We’d started so well. Cover of TV Guide. Great reviews. I was nominated for an Emmy both seasons. But, so it goes.

The Emmy Awards show was a much bigger production than the Tonys back then. We were shooting in New York, so I flew to L.A. for Emmy night. Margo helped me get ready, and my agent served as my date. Afterward, I flew home to my beautifully finished Upper West Side apartment and checked in with the answering service. Somewhere in the years since I’d first moved to New York, my paradigm had shifted from nothing yet to what’s next, and I was consciously grateful for that. Margo and Frankie joined me for a busy holiday in New York, then it was back to work in the new year. The fact that it was 1984 didn’t strike me as portentous at all. And when the answering service told me, “Mike Bennett called for you,” it didn’t even occur to me that they meant Michael Bennett the choreographer and director—Michael Bennett the revolutionary—who’d forever changed both the process and the form of the Broadway musical with A Chorus Line and Dreamgirls. I’d done a reading of a two-woman play for him several years before, so I recognized his gravelly voice when I returned the call.

“I’m working on this new play with music,” he said. “I’d like you to come down and do a staged reading of it. It’s called Scandal.”

He told me the script, written by Treva Silverman, who’d written for The Mary Tyler Moore Show, was “the best book written for a musical since My Fair Lady.”

“That’s huge,” I said, silently adding, if it’s true.

He believed it to be true in that moment; that was very clear.

“It’s about this woman—Claudia—her husband divorces her. Says she’s not worldly, not sexually sophisticated. So she goes around the world to educate herself. Goes to Paris, gets with a French waiter, there’s a Swiss lesbian, a ménage à trois in Italy, and the brilliant thing is, every sexual encounter is a big production number—singing, dancers, the whole thing—because this is how it feels to her as she discovers all these new aspects of herself. But in the end, she realizes that she still loves the husband. And the husband, who has a parallel journey, realizes he loves her, so ultimately, it’s a love story, but it hinges on the arc of Claudia’s personal evolution. Would you be interested?”

“Absolutely,” I said. “Who would I be playing?”

Michael laughed and said, “Claudia.”

I sat there for a moment, waiting for the apostrophe to drop. Claudia . . . ’s sister. Claudia . . . ’s best friend. Claudia . . . ’s bridesmaid who is never a bride. Truth be told, I was already calculating the comic potential of that Swiss lesbian. The last thing I expected when I picked up the phone—or pretty much any moment of my life prior to this one—was to be cast as the leading lady in the next Michael Bennett musical. I have a good ear and good pitch. I’d taken years of lessons and done plays with music. I could sing. But true Broadway divas like Patti Lupone and Kristin Chenoweth can sing. Different thing. I was closer to the Rex Harrison school; I sang like an actor. If critics compared me to the divas of Bennett’s world—or if I allowed myself to compare me to the singing divas of any world—well, as Ethel the Oracle says: “Compare and despair.” But to be in the room with true genius, I told myself, that was worth any amount of heartbreak.

“We’ll have a rehearsal day and do the reading that evening,” he said.

I usually think just about any show is great when I’m in the middle of it, but this show really was an unbelievable dream. Claudia is sharp, intelligent, funny, self-deprecating—not a Swoosie prototype, but a kindred spirit, and I knew I could joyfully play the hell out of her. Michael was as brilliant as I remembered, and here he was even more in his element, chain-smoking, striding around in jeans and sneakers with his shoulder-hunched gait, laughing his seductively abrasive laugh. We worked at 890 Broadway, Bennett’s legendary incubator. The tall windows were always full of lights, day and night, but the energy in the room palpably thrummed when he walked in and drained away when he walked out.

We powered through the long rehearsal day. I went home exhausted and got up the next morning with the flu. Distraught, I called Margo. “I can’t believe this. This is one of the greatest opportunities of my life.”

“Did you take your temp?” she asked, as a mother does.

“It’s over 102.”

“Okay,” she said without a trace of panic, “that’s not good. But you’ve performed sick many times. It’s part of the game. You’ll get a good kick of adrenaline. That’ll help.”

She talked me through all the voodoo we actors perform—vitamin B, gargling vodka—and our fervent little company performed the reading in front of the core people: Michael, his trusted advisors, lawyers, money daemons. Then I went home and collapsed into bed, utterly exhausted.

Michael called me later that night, and said, “Your reviews are in, and they’re raves.”

“Do you think they’re going to do it?” I asked.

“Honey,” he gently reminded me. “I am they.”

During the first six-week workshop, we focused on the book. Future workshops would focus on songs, dances, staging and putting it all together. It paid almost nothing and took up all my time. A lot of people were doing it just for the opportunity to work with Michael. Everyone in the world of New York theatre was well acquainted with the lore: his genius, his passion, his drug use, men and women he slept with, the gifts of prospect and gouts of verbal abuse he heaped on dancers in equal measure.

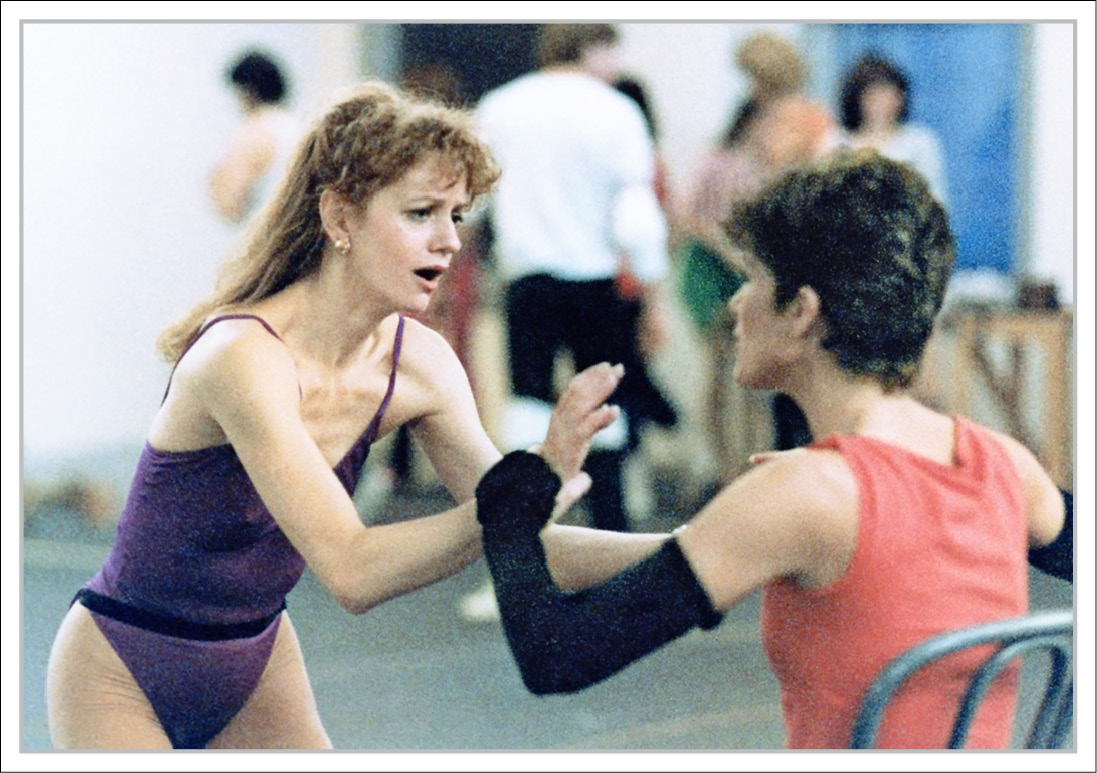

Rehearsing for Michael Bennett’s Scandal in 1984. I was infatuated with Michael and with the corps of beautiful young dancers.

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

Michael Bennett never did anything the ordinary way, and it felt like an extraordinary privilege to be around him. The working hours felt rarified: pure artistic motive, diamond insight, moment-to-moment challenge that left us wrung with sweat and satisfaction. His methodology (which you get a small glimpse of in A Chorus Line) was a total immersion that turned the rehearsal process into an all-consuming love affair with the show. I was infatuated with him and with Claudia and with the corps of beautiful young dancers—the best dancers in NY and therefore the best dancers in the world—who bore me aloft and passed me overhead. I was tossed in the air and caught with abandon, the way you’d toss and catch a toddler. I trusted them completely and loved being in their company. It was like hanging out with a herd of charmingly clever gazelles. Treva showed up with new pages and rewrites every day. During our time off (and by “off” I mean working on our own instead of on the clock), she and I spent many hours talking about the story, the characters, the nature of this beast we were giving birth to.

Almost every night, Michael would call me, smoking, talking hyperbole, saying intoxicating things like, “Watching you work today, I wanted to propose to you. You have line, love. A dancer has to be born with that.”

Fine, I told myself. Be smitten. But get it.

I knew what he was, and he knew that I knew; I wasn’t going to get sucked into the cult of Michael. But these were deep conversations that went on for hours. From May through December, as the workshops went on and our relationship deepened, I gave myself to the hyperbole, heart and soul.

After a few months of this, I went all Claudia and dove into a brief, tantalizing affair—this producer who sparked momentary fantasies about a show biz power couple with a house in Connecticut—so I was less than gracious when Frankie showed up unannounced one night. The sight of him in my space made me feel earthbound again. This was the part of the script where the sophisticated woman meets her unavailable lover in a dimly lit bar, not the part where the grinning ex-war-hero father drops by to change out the ballcock in her toilet tank. There was no way to explain to him that I was breathing differently at the moment, or that what I was doing every day felt like spinning straw into gold, and I didn’t need him coming around uninvited and ballcocking it up with a tank of reality.

“How long are you planning to stay?” I asked with a bit of an edge.

“Oh, a few days,” he said. “Maybe a week.”

“Well, which is it? I need to know.”

Frankie was no amateur with the verbal jabs, and he certainly didn’t spare my feelings when he was expressing his own, but in this moment, he just regarded me quietly and nodded.

“Okay. I’ll let you know.”

I disappeared in a puff of diva smoke, and when I came back, he’d gone, leaving a note that said, “I’ll be at the NY Athletic Club if you need me. Love, Dubby.”

“I feel horrible,” I told Margo on the phone. “I’m sorry. I just . . . I don’t know. I felt the need to speak up for myself.”

Margo was always the consummate Libra. Growing up, she was the middle child of five, and there were times she probably felt like the middle child still, masterfully finessing Frankie on one hand and me on the other in an effort to preserve the peace. She understood without judgment that I was feeling very important, at the center of this great endeavor. The buzzing had begun. Everywhere I went, people would honey up to me, wanting to be a part of Michael’s in-crowd of theatre elites, dying to know what was going on behind that closed door at 890 Broadway.

More important, I was doing some of the best acting of my life and dancing my ass off. Coached by Cleavant Derricks, I was singing this amazing Jimmy Webb music that had been specifically tooled to make the most of my voice. Michael didn’t hear me sing until Cleavant said I was ready, so it was a huge day when he finally came to hear me blow the doors off the Eleven O’Clock Number (as we say in musical theatre) “The Most Important Thing.”

Michael was revved on top of the world to have been proven right. He kept saying, “My Tony-winning actress—she can sing.”

I’d never been in better shape, vocally or athletically, and I’d never been so completely happy. Michael could be harsh; I’d hear him hamstring dancers with cruel remarks, but he treated me like a jewel on a pedestal. Like a star.

I feel a bit chagrined now. Perhaps, up there on my pedestal, I wasn’t getting enough oxygen to the brain. I was oblivious to any friction between Treva and Michael, largely unaware of all the little fights and love affairs that were constantly brewing and breaking up within the company. Some people thrive on all that backstage drama, but I usually forget to pay attention. When it becomes impossible to ignore—when it’s more than a good, healthy argument over creative difference, when it becomes sadistic or cruel or a power struggle—I flee to a neutral corner. Frankie and I chafed each other’s nerves at times, but I wasn’t raised in an atmosphere where people shriek and flail at each other. Personally, I find it disturbing, and professionally, I think it’s an annoying waste of time. The work is challenging enough when everyone stays unruffled.

Given a few weeks off during a chorus workshop, I went to San Francisco to shoot Guilty Conscience, a television movie starring Anthony Hopkins and Blythe Danner, who multitasks as one of my favorite people in the world and one of the finest actresses on the planet. This adroit little script was faithfully adapted from the play, a psychological suspense three-hander about a man, his wife and his mistress and their twisting plots to kill one another. It was a relief to earn a bit of money, and for the most part, it was great fun. There were a few episodes between Anthony Hopkins and the director, who was Welsh, I think, so maybe he reminded Tony of his father or something—I don’t know. The two of them would start thundering away, Blythe and I would look at each other, and one of us would whisper, “Let’s smoke.”

The movie was being filmed almost entirely on location in an enormous two-story house. Blythe and I cowered at the top of the ornate staircase, like children whose parents are fighting. We lit up cigarettes and chatted amiably while Tony and the director tore into each other below, Welsh accents echoing off the woodwork. I confided in Blythe about the heady world I was working in back home in New York. The Times had been preparing a piece on Michael for their Genius series. Treat Williams and I had been written up by Liz Smith and pictured in flagrante delicto in a People magazine spread.

“This is life-changing,” I told her. “I will never be the same.”

Famous last words.

Scandal was finally coming to full flower with sets, lighting and costumes. Costume fittings always make a show feel real to me; you don’t get to the point of fitting costumes until the production is an imminently happening thing. Michael’s shows were always designed by the great Theoni Aldredge, and I loved the miracles she did for my body. I was elated, finally standing there in Claudia’s skin. I was ready.

We knew we were going to be working very hard for a very long time, so a few of the dancers and I decided to go to Saint Bart’s together in January, and I invited Margo to come along. The weather was perfect, and we had a perfectly wonderful time the first few days. The fourth day, we were all lying on the beach, and one of the dancers went in to check with his answering service.

He came out to us, ashen, shaking. “You guys better check in. They told me Scandal is postponed indefinitely.”

We just gaped. I said, “That can’t—no—what—what exactly did they say? What were the exact words?”

“They said, ‘Scandal is postponed indefinitely.’ That’s exactly what they said. My agent told me not to turn down any work.”

The bottom dropped out of my life. The best analogy I can offer is being abandoned at the altar. With complete love and trust, I’d made a huge commitment, closed the door on other offers, and devoted myself to only this. A date was set, announcements made. I’d been fitted for the goddamn dress! Now here I stood, bereft and full of questions. This was before the days when anyone had cell phones. We were in this remote place; it was almost impossible to get a call through, and when you finally did, the operators all spoke French. The stage manager had left me the same cryptic message. No details. No reason. Just an unmistakable vibe of don’t call us, we’ll call you.

Thank God Margo was there with me. While I mourned, she held me and stroked my head. The next day, I sat in numb silence, and she set about the task of getting us home.

Michael called me after we got back. Put it all on Treva. Said she was making eleventh-hour demands, wanted casting and choreography approval. They were going back and forth through lawyers, barely communicating, so I begged him, “Let me talk to her. Please. We can still make this happen.” I talked to Treva, and she was in a baffled panic, scrambling to appease Michael without completely screwing her own interests. Rumors had begun swirling that Michael had had a heart attack or heart trouble of some undefined nature, and then that became the story: Michael’s heart trouble. Then it was, no, not that, something about the money. No, it was all that sexual overtone, what with this whole new awareness about high-risk behavior and everything. The only solid piece of information I got was that Michael had gone to London to direct Chess on the West End.

“You’ve given it all the time it deserves,” Frankie advised. “Shake it off and move on. Keep chopping wood.”

“Yes, why don’t I just do that?” I said bitterly.

Easier said than done. I was heartbroken. And I was angry. I turned forty during those workshops. The only thing that really changed was that I no longer laughed at the old joke about how, in Hollywood, they euthanize you when you turned forty. Nonetheless, this show took a year from the middle of my performing prime, and my dear, those days are numbered for an actress just as surely as they are for a professional athlete. We must carefully choose where to invest our time, because every day of our professional lives, time and gravity are doing their merciless thing. (My tits have migrated three centimeters to the south since the beginning of this paragraph!) There was no getting back that lost year, but the brutal financial blow meant nothing to me compared to what I had emotionally invested in this show. “Can’t forget what I did for love,” as the song says. It also says “won’t regret”—and it took me a while to get there. But Frankie was right. Bemoaning it served no purpose.

I took a nice part in the movie Wildcats, playing Goldie Hawn’s sister. It was like rehab or like a sojourn at a sanitarium, the way ladies sojourned back in the day if grief or consumption got the better of them. Goldie is generous and outgoing and has a vivacity that energizes the people around her. I quite idolized her. She had everything worked out, the way one does if one is good at being a movie star: snacks at the right time, warm coats, lots of water, inner peace. We were up early and eating healthy. Goldie had us all happily doing aerobics during lunch. Everyone was cared for. No one was on a pedestal. A lot of my scenes ended up on the cutting room floor, but I was so grateful for this healthy work experience. It was the unbuttered wheat toast and Pedialyte cure for my Michael Bennett hangover.

While I was on the set, I got a call from the producer of True Stories, directed by David Byrne of Talking Heads.

“Here’s the thing,” she said. “We can only pay union scale. And it’s a no-frills situation as far as—”

“I’ll take it.”

I got to marry John Goodman in bed. Who turns that down? (Turns out, Betty Buckley did, actually. I was their second choice and glad to have it.)

A while back, I saw Stockard Channing at some event or other, and when I asked her what she was working on, she said with a philosophical shrug, “The tide’s out right now.” Such a lovely way to put it. The work comes in waves. That’s something I love about this life. One night, you’re sitting there counting crickets, and the next morning, two opportunities are on the table, and you have to figure out how to fly back and forth between Hong Kong and exotic Alabama or make Sophie’s Choice and let one go. (Chatting on set several years ago, I told Elisabeth Shue how much I loved Leaving Las Vegas, and she said she’d been up for Waterworld with Kevin Costner at the same time. Talk about a rising tide . . .)

The key to happiness is learning to enjoy the quiet moments, using them to gather the strength you’ll need to enjoy your next ride on the rollercoaster. I’d love to say I finally have a handle on that, but I’d be lying. I go to a dark place sometimes when I’m between jobs. My family and friends have come to understand that I’m fully present in my work, so I suffer in its absence. Adrienne Rich wrote in her elegant poem about Madame Curie: “She died a famous woman . . . denying her wounds came from the same place as her power.” I’d like to think it’s a bit like that—to a lesser degree, of course—with tragedy and comedy instead of radium and polonium and a couple of Tonys instead of the Nobel.

Omaha, 1941

The other reason I kept imagining Frank near Manila was the phone call that rang in our house at seven o’clock on the morning of December 19.

“Margo, quick—quick, get up—the phone. It’s about Frank!”

And I stumble to the phone, asleep and awake in the same instant, almost, and the operator is reading me a message from Frank.

It’s from Manila, but there is no date. But I hardly miss that yet—it is saying, “Am doing all right under the circumstances.”

The second time I make her read it (I always do this, it’s such pretty music)—I realize, this second time, she has started the cable, “Beloved flower.”

Now you think these are rather soft words for a man who’s been dealing in cold blood. They are soft, and Frank doesn’t usually talk that way; but Frank said them over ten thousand miles for me to hear the softness. They told me a lot of other words.

These are quiet words, but I guess strong words are always quiet. And quiet words never seem to go away. It was Frank’s own voice, speaking in the cable, not someone else making up a message for him. That was something so sure to hold to.

But then, when I had been staying a long time with the strong things this cable let me know, I began to realize how much it couldn’t tell me, too. There was something very puzzling. After Frank told me he was “doing all right under the circumstances,” he said: “Wire Eddie’s brother.”

Why hadn’t he said anything about the rest of the boys?

Margo sits at the table, and I can feel her waiting for the other shoe to drop. The worst kind of curiosity. Not only is the answer out of reach, she’s forgotten the question, which is a mercy, because of course, all the boys were dead, burned alive on the tarmac at Clark Field just a few days after Pearl Harbor. This is one of those times when Margo’s bewilderment, as upsetting as that can be for her, is better than the memory that lies beyond the haze. The source of her uncertainty is nothing she can articulate, nothing I can guess at; quizzing her about it would only make it nag at her more deeply.

It’s uncanny how much her present state of mind resembles Bananas’s in The House of Blue Leaves. I gleaned bits and nuances from Margo’s mannerisms when I created this character, but I never suspected I was peering through a keyhole, looking at Margo’s future. Her poetic dementia.

John Guare’s darkly quirky comedy was workshopped at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in 1966 while I was off learning the London tube system. In 1986, Jerry Zaks was directing a revival, and when he called me to audition—I have to be honest here—I read the thing and didn’t understand it. I didn’t get the jokes or even the gist of the story, which involves a zookeeper who wants to have his schizophrenic wife (Bananas) committed to a mental hospital so he can run off to Hollywood with his mistress (Bunny) to pursue his dream of writing music for the movies. And their son, who has gone AWOL from the army, is planning to blow up the pope, who happens to be in town that day. Really, it’s the definition of “you had to be there.”

I was asked to read for Bunny, which was great with me. Bunny had more lines, bigger laughs, cuter costumes, lots of lovability. Bananas, meanwhile, spends half the play in a bathrobe, haunting the upstage windowsill and saying strange, arcane things like, “I can’t leave the house, my fingernails are all different lengths.” Until you learn to love the poetry of her, she has the potential to be rather sad. Obviously, Bunny was much more up my alley, so I worked up a few terrific Bunny monologues (of which there are many) and trouped off to the audition, where they did a complete 180 and asked me to read for Bananas.

“We know what you can do with Bunny,” said Jerry. “Would you mind reading Bananas? Take a few minutes—however long you need. Do the green latrine speech for us.”

“The green . . .”

Apparently, this is a monologue that gets done all the time for auditions and competitions. I was completely oblivious.

“Could you talk me through it?” I asked.

He talked me through it. I still didn’t get it.

The Green Latrine is a Buick that Bananas is driving in a dream, and she comes to an intersection where Jackie Kennedy, Cardinal Spellman, President Johnson and Bob Hope are all trying to hail a cab. Only two words in this monologue made sense to me: Bob and Hope. But I gave it my best shot.

My agent at the time, a very nice British woman, called and said, “Well, you’ve been offered Ba-nah-nahs.”

“I wanted you for your wrists,” Guare told me later.

The less poetic version: Stockard Channing was already on board, and given first choice of the two roles, she took Bunny, just as I would have done had I been in her shoes. Nonetheless, my friends kept telling me what a great play it was and what a great role Bananas is, and I knew the people involved would be great to work with, so I dove in.

At the first reading, my heart sank further. Stockard was terrific in this role and made the most of all those lavish monologues and big laughs. Our castmates, John Mahoney, Christopher Walken and Ben Stiller, were all familiar with the play. Ben (who was making his stage debut) had seen his mother, Anne Meara, playing Bunny in the original off-Broadway production. I alone was a House of Blue Leaves virgin and largely in the weeds.

“I’m so lost,” I told Margo that night. “I don’t know what I’m doing. I feel like I’m invisible. I can’t even tell you what this play is about.”

(Ironically, this is exactly what Bananas feels, so I was on the right track, I just didn’t know it.)

Margo said the perfect thing: “Why don’t you just quit?”

“What? No! I’m going to figure this out. Just because it doesn’t jump up and kick you in the head the first time you read it doesn’t mean . . . oh.”

Even over the phone, I could tell she was smiling smugly.

I lay in bed at night, turning the lines over in my mind.

I don’t like the shock treatments, Artie. At least the concentration camps—I was reading about them, Artie—they put the people in the ovens and never took them out—but the shock treatments—they put you in the oven and then they take you out and then they put you in and then they take you out . . .

Jerry Zaks’s direction was a master class: “Swoose. Swoosie, dahling. You’re the most normal housewife in Queens. Your husband works at the zoo, and you’re the most normal couple in Queens. With your first line—‘Is it morning?’—you just want to know if it’s morning.”

Throughout the entire run, Jerry continued to give all of us notes, which I lusted after and squirreled away for future reference. The breakthrough moment for me was when he said, “I need a sound from you every time she has a fit. Some ungodly, heart-wrenching sound. Then it needs to be a light switch change to a calm, serene ‘Look at me, I’m a forest.’ No transition.”

That night, sitting on my living room floor, I thought about the epileptic fit I had to do in Marigolds and about the night sounds in a zookeeper’s nightmares, and the sound reeled out of me. I have no idea where it came from, and I suspect my neighbors were equally baffled.

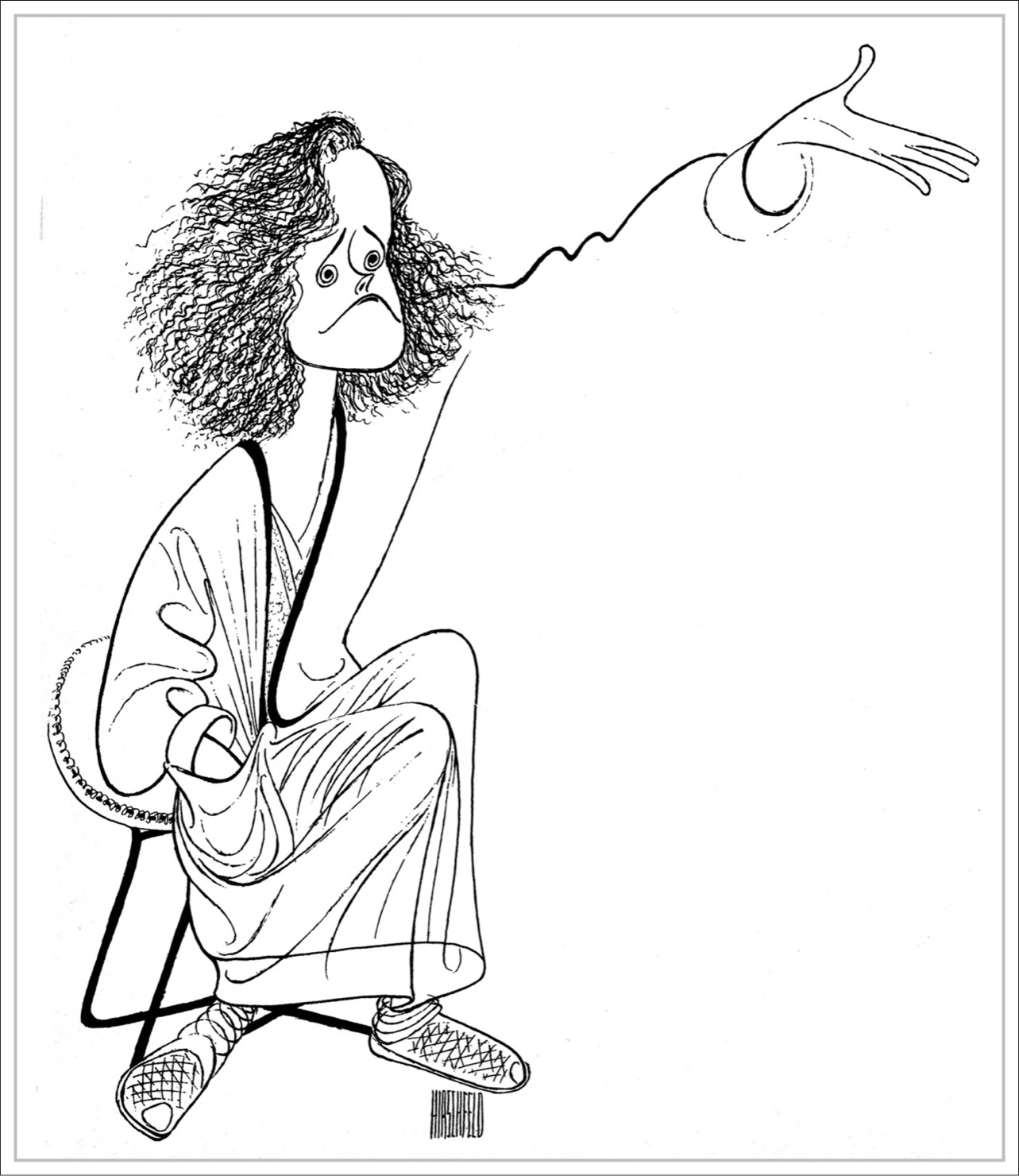

Al Hirschfeld’s heart-wrenching rendition of Bananas in The House of Blue Leaves

AL HIRSCHFELD

Ann Roth (who also designed my Eighth-Avenue-not-Park-Avenue hooker garb for The World According to Garp) tried about six dozen bathrobes on me to find the one with exactly the right amount of weariness in the nap and buttoned it one buttonhole off kilter, which set the you don’t have to tell us who you are tone.

I have to laugh now, because Margo’s favorite robe is her staple wardrobe item. We have to go through all sorts of machinations to get her into something else long enough to launder the thing, and there are times when this is not worth the stress. Last year, we all gave her robes on her birthday in hopes of getting a rotation going.

At the time of Blue Leaves, Margo was a healthy, young-hearted seventy, still sharp and ready for anything, but starting to display some eccentricities. Her classic one-shoulder shrug was an easy bit to steal. The rest was more instinctive, subconscious even, particularly—though I don’t want this to sound wrong—the scene where Bananas morphs into an eagerly affectionate little dog, guileless and cheerful, but with a vaguely dark under-current of insistent need. I certainly wouldn’t have said so to Margo at the time, but I’d seen flashes of that in her devotion to Frankie. For the most part they were the dynamic duo, but their marriage—like any other marriage—went through passages of imbalance, and in those moments, it was debatable who had whom on a leash.

It wasn’t until much later that I recognized how Bananas had inherited Margo’s longing to fly, her wistful remembrance of past glory days, her willingness to please coupled with an unwillingness to keep quiet about something she knows is not right. There’s her lonesome love for her distracted husband. She remains calm at his sudden outbursts, her flashes of anger and sadness firmly held at bay—until they’re not, and she suddenly turns on him with rage, standing up for herself. Maybe as marriages go, all that is just another day at the office, because in a kinder, gentler way, it was all heartrendingly familiar.

It’s uncanny how the lyric language of Bananas’s craziness foreshadowed the frangible reality Margo lives in today, and having lived in Bananas’s head for quite a while, I’m less frightened by Margo’s dementia now. I’m able to let go of the urge to correct and reorient her, because I get that she is perfectly oriented on the only plane that makes sense to her.

I felt fairly confident by the final dress rehearsal, and the first night of previews, I knew I’d found it. This play knows no “fourth wall”—the actors speak directly to the audience at times, and it doesn’t really work until the audience becomes part of it. Toward the end of the show, Walken’s character even says, “The greatest talent in the world is to be an audience.” The audience arrived, and I understood. This role was a turning point. Life-changing.

Tommy Schlamme and Christine Lahti came to a matinee, and it was so good to see them backstage. Tommy gripped my hand and said, “There’s someone here to see you.”

It was Michael Bennett.

I went cold and hot and weak and strong all at once, and the urge to get my arms around him won out. I suddenly realized I wasn’t angry anymore. I couldn’t remember when I’d let it go, but I knew it had been a while.

“How is your heart?” I asked him.

“It’s okay. How’s yours?”

“It’s okay.”

“You were spectacular. Did you see Frank Rich’s review in the Times?”

“No!” I clapped my hands over my ears. “I never read reviews while the play is running, especially if it’s a wonderful review. If the reviewer says, ‘I loved the way she tilted her chin,’ you’ll never get that chin tilt right again.”

“Honey,” said Michael, “lock yourself in the bathroom and read this one.”

He knew I wouldn’t—and I didn’t—but it was impossible to ignore the way the audience reacted; within a few days after we opened, we knew we’d be moved to Broadway in time for Tony nominations.

“I’m so glad this happened for you,” Michael said before he left. “If it hadn’t—honey, I would have slit my wrists. I felt like I owed you a year of your life.”

It meant everything to hear him acknowledge that and to see that it caused him genuine sorrow. He didn’t apologize or offer any further explanation. That’s not how this business works. We parted with Hollywood half kisses and the standard promises to keep in touch, but there was more emotion in it than usual, both sadness and affection.

Before the Tonys, Brent Spiner sent me a telegram: “I think your Tony’s going to have a twin sister.” He was right. Stockard and I were both nominated, and I won. (If that bothered her at all, she avenged the decision by getting cast in Six Degrees of Separation, which I coveted mightily. So goes the tide.) John Mahoney and Jerry Zaks also won Tonys, and the following year, PBS filmed The House of Blue Leaves for the American Playhouse series with Christine Baranski coming in for Stockard.

The show had a luxurious long run. We were a tight-knit cast and went as a gang to a nearby coffee shop after most performances. One night after the show, several of us walked out the stage door and across the street to see True Stories playing in the New York Film Festival, which was kind of a gratifying little Swoosie-palooza.

Things continued to ebb and flow. As the years went by, I was lucky enough to work with so many people that it was almost impossible to go to an audition or show up for a shoot where I didn’t know anyone. Every time was a reminder that the industry had become my extended family—especially the New York theatre community.

As the 1980s unfolded, the AIDS epidemic took a terrible toll on Broadway, especially among the dancers. The first of my friends to die was Peter Coffield, my castmate in Tartuffe and in the A. R. Gurney play The Middle Ages. This was in the fall of 1983. Gurney had gone to see him in the hospital, and he told me, “They said he had pneumonia. They made me put on this mask.” A few weeks later, we heard that Peter had died. We didn’t understand yet, but it was dawning. At first, there was fear—no one knew what this thing was, how it was spreading, why nothing was being done to stop it—then the gravity of it settled over us. The funerals and missing pieces, the dwindling numbers at the dance auditions, the disappearing directors, playwrights, actors and producers. It felt as if we’d lost an entire generation.

Of course, it eventually came out that Michael Bennett’s vaguely defined “heart problem” was in fact AIDS. He’d known it when the dancers and I went to Saint Bart’s. That was the real reason he’d pulled the plug on Scandal. Even if he could have gone on working for a while, sooner or later, the truth would have come out, and the meaning of the play would have been forever changed, tinged with an irony that undermined its buoyant spirit.

During the summer of 1987, word traveled through the grapevine that Michael had bought a house in Arizona, and he was dying. He called me in June and said, “Honey, I just got a brand-new car. Rolls-Royce. Top of the line.”

I heard his voice and started weeping. (I thought about this later during And the Band Played On; I play a character who’s told she has AIDS, and her first task is to comfort her sobbing husband.) Michael sounded fragile but still strong and acerbically funny.

“You should come and visit,” he said.

“I would love to see you, Michael. When can I come?”

“Soon. Don’t come now, though. It’s monsoon season.”

“In Arizona?”

“Yeah. This is not a good time. But soon.”

I was grateful to get the call from Michael’s longtime assistant two weeks later before I saw on the news that Michael Bennett, the revolutionary choreographer and director, the innovator who’d given us A Chorus Line—which was, at that time, the longest-running musical in Broadway history—had died at age forty-four.

“You say every character you play gives you a gift,” says Ethel the Oracle. “Did the fact that the show never opened take away Claudia’s gift?”

I have to ponder a moment before I honestly answer, “Almost.”

But with equal honesty, I can say that it would not be possible to be in a room with Michael Bennett for a year and not come away in some way blessed by his mercurial, unpredictable genius. I told myself that first day that it would be worth any amount of heartbreak. Famous last words. But from the here and now, I do see that I got more than I gave.

This character was so like me—same rhythms, same intellect, same slanted, slightly sardonic view of the world, my voice with a stage spin on it—as though it had been written for me, but it wasn’t. She refused to fall apart after her husband left her; she was proactive and chose to grow. I love the old saying, “If you fear the lion, walk up to the lion.” Claudia showed me how to walk up to the lion, and I never forgot.

The article for the Genius series in the New York Times never happened, but after Michael’s death, the writer, Barbara Gelb, wrote an important piece about Michael, “First, Last and Always a Dancer.” In it, she mentioned his mysterious, last-minute abandonment of a fully staged musical called Scandal, which had evolved, like A Chorus Line, “through a prolonged and painstaking workshop process.” She said, “I spent several months watching him ready Scandal for its Broadway opening, for an article that was aborted when the show was. Like the handful of others who saw it, I knew it would have been the best thing he’d ever done.”

Last night I had a vivid dream that I was standing in the California sunshine, and Margo picked me up and tossed me and caught me, the way you’d toss a toddler in the air and catch her and kiss her and set her down safely.

I woke up waiting for the other shoe to drop.