CHAPTER TEN

Degrees of Separation

Omaha, 1943

The first time I saw war was in a man’s eyes. It was a sergeant in the Air Corps, who stepped off a plane at the Municipal Airport in my city. I approached him as he came through the passenger gate. I said, “Sergeant Catarrius?”

His khaki uniform was dusty and spotted, and his leather jacket was worn thin and scratched raw. This sergeant had a thin face. Is Frank’s this thin by now? His eyes look off into the distance, somewhere, and they look hunted. Could Frank’s eyes look so hunted, tired, and frightened? Would I know them now?

I’ve heard lots of radio commentators talk about war, but their voices never sounded like this man’s. He doesn’t tell me the big picture of war, the percentages and the logistics that the Congressmen and the newspapers give. They tell me “intelligent” war, all the black and white facts of this new business we are in.

“They found us again in Broome, Mrs. Kurtz, when we landed in Australia. We felt safe at last and then at daylight, they came in again, a skyful of them. I’m used to seeing soldiers and officers bombed, after Clark Field and after Java, but to watch them bomb women and children who didn’t have a chance—to crouch there in a foxhole and watch their bodies cut to pieces. We are all very tired, Mrs. Kurtz.”

Right now I’m glad he doesn’t look at me—I’m not ready. And I know now, sitting next to this man who comes from war, the job at home is not only to get guns and equipment to the boys at the front, but we have to learn to be ready for these eyes. We need to be ready, to be ready for when they finally, someday, turn to us.

Will Frank and I ever look at each other again, or will he be looking off to the distance, somewhere?

“We are all very tired,” the sergeant said.

And this is how war comes to someone at home.

On Pushing Daisies, Ellen Greene and I played two synchronized swimming sisters. I was Lily, whose exotic backstory includes the loss of one eye. This was deeply affecting to me in a completely unexpected way. Late in his life, you see, Frankie had lost the vision in one eye and went through hell, but I never really understood the enormity of it until I got inside Lily’s skin. Sometimes a character’s secrets manifest from the outside in: Bananas’s bathrobe, the exoskeleton of corsets and lace in Dangerous Liaisons, the faux fur of the hooker in The World According to Garp, Honey’s catalog-clipped ensemble in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

The costumer placed Lily’s bedazzled silk patch over my eye, tilting the world just enough to make a difference in my balance, planting the seed of a vague but persistent headache. Having no depth perception is only one of the challenges, I realized. When I looked around the room, I could still see perfectly well, but somehow, wherever I looked, there was this palpable void looking back at me. Putting on the eye patch before every shot, I thought of Frankie, of the vulnerability to which he could never become accustomed and his anger at having part of himself so abruptly truncated. I remembered the ever-present sediment of bitter frustration that seemed to collect in him after that, and I put that into Lily.

Before this happened, Frankie was in tiptop health. A hale and hearty seventy-five, he was not thinking about retirement any more than I think about it now—meaning not at all. I went as often as I could to see him speaking, and he was a natural, which is not to say he didn’t practice. He put the same assiduous effort into preparing for these performances that he put into the old aquacades. Just as she had back then, Margo sat in as his coach, giving him notes and keeping him impeccably styled. He’d get up there in his signature bow tie and have the room in the palm of his hand. People lapped it up and loved him. Great delivery and rhythm. I definitely inherited my comic timing from him. Candidly, I cringed at some of his one-liners, but he always got huge laughs.

“So the psychiatrist says to his patient, ‘Do you ever talk to your husband during sex?’ And the lady says, ‘I suppose I could. There’s a phone right there by the bed.’”

You could almost hear the rim shots.

“They tell me Nixon is looking to buy a house in New Jersey. Hasn’t this poor man suffered enough?”

Frankie and Margo continued to visit me frequently during those years, and overwhelmingly my memories are about what fun we had. They were always my best pals and favorite cohorts, game for anything from the time I was a teenager, all uptake and liftoff. If I said, “Let’s go to Easter sunrise service at the Hollywood Bowl,” alarms were set and coffee poured into thermoses. Someone was always coming up with a great idea—visit Pasadena, tour a museum, hunt up a book—I don’t recall anyone ever saying, “Nah, not in the mood” or “maybe some other time.” We went to baseball games, movies, shopping. There was Randy Newman at Avery Fisher Hall and Bobby Darin at the Copa. There was even an Orson Welles sighting at the unfortunately named Tail o’ the Cock restaurant. We even went to Vegas a few times. (Frankie was a natural gambler who’d built his life on an addiction to calculated risk, and Margo, as you may recall, had grown up with poker players.)

In 1985, Frankie and Margo came to see me in yet another incarnation of The Beach House, and while they were in New York, Frankie suffered one of those little TIAs (a transient ischemic attack or “mini-stroke”) while he was brushing his teeth. He felt basically fine, but Margo noticed his speech had become oddly slurry. I had to do a matinee, so a friend took them to see a doctor—a star doctor who was supposedly the guy for this sort of thing, which was supposedly a fairly routine operation to clear the carotid artery. Why didn’t we get a second opinion? Margo and I grilled ourselves in retrospect. Why didn’t we insist he have it done at Mayo?

The operation was botched, the optic nerve severed. Frankie, who’d zealously guarded his health all those years, felt maimed, robbed and benighted. He still had good vision in his remaining eye, so he was able to continue driving and do all the things he was accustomed to doing—not to mention all the things I was accustomed to having him do for me. There was much to be grateful for. He was, overall, in stellar shape for a man his age. But this was a major thing. It changed his life, changed him. Sadly, I wouldn’t understand how deeply and why until thirty years later when Lily revealed it to me, quietly but without pity, long after Frankie was gone. In the same moment, I understood that I’m now capable of compassion I simply didn’t have back then.

Back then, as Frankie found his new normal, I was focused on my own plate-spinning act, steadily working, constantly traveling. I wasn’t ready to confront the fact that my father was getting old, that there might come a time when he would need me as much as I had always needed him. Frankie was happy to facilitate my denial. He liked being needed, being the hero, grounding me with wiry pragmatism, clotheslining me with an unsparing joke. He and Margo were both happily aware that their unconditional love was the steady fulcrum I needed as my life continued to seesaw between the ridiculous and the sublime.

Sometimes a character’s secrets manifest from the outside in. From Eighth Avenue to eighteenth century with Robin Williams and Glenn Close in The World According to Garp (1981) (top) and Glenn Close and Uma Thurman in Dangerous Liaisons (1988).

WARNER BROS.

In 1988, I was offered a part in the film of Dangerous Liaisons, which I kept turning down, until John Guare physically took me by the shoulders and said, “Swoose, you are doing this.” Glenn Close was on board, along with John Malkovich and Michelle Pfeiffer. I’d be playing Uma Thurman’s mother. People kept telling me I’d have a great time, and I did.

We shot in Paris for ten weeks. My French steadily improved as I settled into the pleasant neighborhood surrounding my hotel where I could see the Eiffel Tower from the bathroom window. The costume designer, James Acheson, who’d just won an Oscar for The Last Emperor (and would win another for Liaisons), did not cheat on a thing. He piled it on, layer by authentic layer: crinolines, corsets, hoops. It was easier to lean against a tree and close your eyes than to try to lie down for five minutes. Glenn had her baby girl with her, an adventure in itself, but additionally challenging when bending over to adjust one’s own shoe buckle was a three-man operation. Eyeing the narrow door of the Porta Potty in utter despair, she and Uma and I compared notes:

“We have an hour for lunch. Are you taking off your corset?”

“That’s like taking off your boots on an airplane. Don’t even go there.”

“Three words: Eat. No. Bread.”

“I won’t even go into what it was like trying to change a Tampax,” I told Margo when I got home. “On the upside, there was Courvoisier on the craft service table at lunch every day. You don’t usually see that.”

After that, I was flying back and forth between coasts, making A Shock to the System with Sir Michael Caine and The Image with Albert Finney. The two of them kept giving me messages to courier to each other:

“Albert, Michael says go fuck yourself.”

“Michael, Albert says same to you with love.”

(Joanne, the driven television news producer in The Image, was not an outside-in character; I did a research deep-dive with help from Don Hewitt and Mike Wallace at 60 Minutes and Peter Jennings, who let me sit beside him, just off-camera, while he delivered the evening news.)

I moved on to Love Letters onstage in New York, and one night John Guare dropped by the theater to bring me a script—his new play, Six Degrees of Separation—which I immediately consumed and loved. This character, Ouisa, so resonated with me: her intelligence and urbane wit, her willingness to trust and to be open to connection even after her trust has been shattered.

“It’s brilliant,” I told him (though I’m not sure I’d absorbed yet just how brilliant it really was). “I want to play the young black guy.”

I felt I had a good shot (at Ouisa) because the last John Guare play I was in was The House of Blue Leaves, and I’d won a Tony, so there was a happy history there. A love fest. Jerry Zaks was set to direct Six Degrees at Lincoln Center, and I had just done a staged reading of Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins for Jerry Zaks where I played Squeaky Fromme alongside Nathan Lane and Christine Baranski, which was a blast. Jerry took me out to dinner, which was pleasant enough, but the purpose was a bit murky. I had the disquieting feeling that I was auditioning, but I didn’t know what I was supposed to do.

Long story short, they cast Blythe Danner, and knowing I needed to vent, Frankie patiently listened to me unload about it at home in Toluca Lake.

“I appreciated that Jerry called to tell me himself, and if not me, yes, of course, I’m happy for Blythe, I love her, but . . .” I sighed. “Moving on. I’m just sad this play won’t be part of my life. I really loved it.”

“What else are you being offered?” Frankie asked.

“There’s an interesting pilot at NBC. They’re calling it ‘the Sisters Project.’”

Frankie and Margo knew well by now that there were always pilots being pitched, and I was rarely interested in doing one. My upscale New York theatre niche suited me as comfortably as my Upper West Side apartment. Back then, the toniest theatre folk tended to think of TV as slumming (unlike now, the golden post–Mad Men reality), but this script was literate, grown-up, and funny from the very first scene, which had the Reed sisters in a steam room discussing the possibilities of multiple orgasms, to the emotional dénouement, which had them crossing paths with their younger selves in the empty rooms of their childhood home. The characters were warm and flawed, struggling with themselves and each other. It was created by Dan Lipman and Ron Cowen, a playwright who’d won a Drama Desk and been nominated for a Pulitzer. They were trying to get Sada Thompson to play my mother, and even if they couldn’t get her, I thought, the fact that they wanted her was a good sign.

I was literally on my way out the door, when my agent called, telling me they wanted me for Sisters, and I should stay in L.A. and work it out.

“I’m on my way back to New York,” I told him. “The car is out front waiting to take me to the airport.”

He said, “Put your bags down. This is serious.”

I sent the car on without me, and Frankie and I sat at the kitchen table. He poured himself a glass of milk, took a yellow legal pad and drew a line down the center.

“Okay. Pros and cons.”

Right away, on the upside, I could see that if the show got picked up, I could be living at Frankie and Margo’s for the better part of five years. That was also a downside. Frankie had a my-way-or-the-highway approach to folding towels and parking the car, and I cringed to hear the way he barked at Margo for whatever little or big thing was out of place in his world.

An old joke he repeated over the years: “Sometimes I think you were born twins: Margo and an idiot. And Margo died.”

Somehow it didn’t sound so playful anymore, and at some point, Margo’s laughter at the old joke started to sound a bit off key. He had a way of asking the hard questions and compelling self-honest answers, and generally, I appreciated that, but diplomacy had never been his strong suit. His idea of tact was to preface his unvarnished opinion with “Now, this isn’t a criticism, but . . .” The starchier side of Frankie’s character wasn’t aging well. His impatience hardened to anger much more quickly than it did when he was younger. Frankie had the ability to inspire and enrage me like no one else.

“It’s a huge commitment,” I said, “but they’re offering me a good deal. My agent says they think getting me will help them attract some other good people, so there’s some leverage there.”

Frankie listed all that, and we went back and forth, bouncing thoughts and questions. At the end of the day, I decided to sign on for the Sisters Project. I went to bed feeling blessed and loved and lucky to have Frankie in my corner.

I was the first sister cast (Alex), so I had the opportunity to sit in and read with the actresses auditioning to fill out the quartet. Patricia Kalember, cast as Georgie, was the next Reed sister to come onboard, then Julianne Phillips as Frankie, so the three of us were there the day Sela Ward came in to read for Teddy. It was evident in that moment that the four of us had that elusive chemistry you always hope for. With lovely Elizabeth Hoffman as our mother, we dove into shooting the pilot episode of Sisters. There’s almost always a honeymoon period in the early days of a show, but I felt we had something beyond that. It was a mellowed, more mature version of an uncommon sorority I’ve experienced with only a few other ensembles over the years.

It’s a high-diving horse trick for writing to be as gentle and humorous as this and still be groundbreaking. That steam room scene is, in microcosm, exactly how the show eventually found its audience. First we hear voices through the heavy clouds. Girl talk. We can barely make out the sisters sitting close together, wrapped in towels. The girl talk eventually leads to comparing notes on multiple orgasms.

“I had five once,” says Alex. “New Year’s Eve, 1981.”

“What a memory!”

“What a New Year’s . . .”

The scene was a perfect vehicle for all the exposition that needs to happen in a pilot. Immediately we see Alex’s sterling pragmatism, Georgie’s earthy honesty, Teddy’s over-the-top bravado, and Frankie’s longing to keep up. We also get a sense of the pecking order. But as the sisters go their separate ways, something extraordinary happens: an unseen woman somewhere in the room softly says, “Eleven.” And another says, “Seven.” Voices ripple through the steam, each one as sensual as a glimpse of wrist bone, saying exactly what so many women were about to say in response to this show: You haven’t seen us, but we’re here. And we really do want to talk about all these things we’re not supposed to talk about.

The day before we finished shooting, Frankie called me at the studio. “Jerry Zaks is trying to get in touch with you.”

Blythe had left Six Degrees. “Due to a family emergency” can be code for all kinds of things, so my first thought was, I hope she’s all right. My second thought had a cynical edge I didn’t like feeling. Oh, so now I’m right for the part?

“I guess you heard we’ve had a little crisis,” Jerry said. “But I understand you’re in the middle of a pilot.”

“We finish shooting tomorrow. We won’t know for a month if we’re picked up, and if we are, we probably wouldn’t be shooting again until the end of the year.”

When we hung up, the tantalizing possibility of this play was hanging in the air again, but by the time the pilot wrapped, it was gone again. Long story short (I never heard the long version), they cast Stockard Channing. Six Degrees of Separation was hailed as the second coming, she earned the reviews we all envision in our sticky little dreams and was cast in the film, for which she would later earn an Oscar nomination. She really was magnificent in that role. I can’t tell you how delighted I was for her.

Seriously. I can’t.

It would be considered unbecoming to admit I ate my heart out. We’re supposed to air-kiss these things good-bye and graciously walk off the stage like smiling pageant hopefuls, and we do that for the sake of propriety and so we can remain friends, but the truth is, almost every single one of us is harboring a ravenously covetous creative tapeworm. Without it, we wouldn’t be in this business at all.

Moving on.

The Sisters pilot was shown to critics in January 1991, and the predictable howl went up about the opening scene—not in response to a lingering shot of a woman’s backside in silk panties, but about “all that orgasm talk,” which the producers had gotten past Standards and Practices and showed when I was a guest on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. Now they had to sell to advertisers and convince them that it would play in Peoria. As local affiliates started grumbling, Ron Cowen spoke up to defend what he felt was a “signature scene” similar to the roll call scene at the beginning of Hill Street Blues or the stand-up club at the beginning of Seinfeld. NBC’s president, Warren Littlefield, issued a good-humored statement: “Corporately, we believe in orgasms.” Disappointingly, when the dust settled, the shapely backside remained, but the intimate conversation between the sisters would be cut when the pilot aired in May. (It was later restored, and at this writing, you can see it in its entirety on YouTube.)

This was a different day and age in the television industry. We had no idea if we were going to get away with banter about orgasm or any of the other intimate subject matter being addressed or if audiences accustomed to a steady diet of MacGyver, Magnum, P.I. and Baywatch would embrace a thoughtful show about the kitchen cupboard wisdom, private triumphs and quiet disappointments of suburban women. On the upside, the show was different, which made it a creative joy. On the downside, the show was different, which made it a commercial long shot. When it was time for “upfronts”—a sort of flea circus in which the stars of all the network shows are marched before the media and potential advertisers in an effort to generate buzz—we Reed sisters gave it our leggy best. We would have preferred being heralded as one of the smartest shows on television, but if having the best gams got us picked up, we’d take what we could get for the moment.

Afterward, I had a break in my schedule, so Margo and I went to Hawaii to hike around the flowered trails and huddle like baby turtles under our beach umbrellas. The first day we were there, I was happily surprised when the Sisters line producer called to tell me we’d start shooting in October; the show had been picked up for six episodes.

When I called to tell Frankie, he predicted, “This show’s going to go for five years.”

“I don’t know. They’re not ordering a full season, but with all the tempest in the teapot, I’m grateful we had a chance to hit our stride.”

“Five years,” he said with certainty. “At least five, maybe six.”

In my ear at that moment, five years sounded like a long time. But we could discuss that later, I figured, because it’s human nature to think there’s always a lot of later lying around—until there’s not. A month or so after Sisters premiered, we celebrated my father’s eightieth birthday. As he predicted, the final episode would air five years later, just a few months before he died. I don’t know if I was imagining that he’d go on, invincible as ever, until I was eighty myself, or if I was simply incapable of imaging my life without him.

Or maybe it’s just something about Hawaii. When you’re there, you feel like you have all the time in the world.

“Frankie, Margo and I were thinking we might stay on here a little longer. Do you mind being a lone wolf for an extra week?”

“No, by all means, stay. You’re there. Make the most of it. Have a good time.”

The next day, Frankie called me at the hotel. “Jerry Zaks is trying to get in touch with you.”

Stockard was leaving the play to shoot a movie to which she had a previous commitment. They wanted me to come in and replace her for three months. I felt a jolt of No, thanks, I’ve just put one out, but I kept that to myself and told Jerry I’d think it over.

“What’s to think about?” Frankie said bluntly. “You said you wanted this play in your life. Then your pride got hurt. Which one means more to you?”

I could honestly answer, “The play.”

“Besides,” he harrumphed, “what’ll you do all summer if you don’t take it—sit on your ass?”

Part of my hesitancy was the fact that I’d never replaced before. It’s like you’re standing on the platform and they’re asking you to jump on a ninety-mile-an-hour train. Back in New York, I sat in the audience and watched Stockard, stole everything I could and made it my own before she left and I stepped in.

You bring your unique heart to the character when you replace another actor, but you have to fit into the play as everyone else has already rehearsed and performed it. There’s also an element of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”; it’s likely your predecessor—with the director’s input—will have come up with bits and business that just plain work. You learn as much as you can as quickly as you can and dive in without the benefit of a long rehearsal process. (I’ve often said I could happily spend my life doing nothing but rehearsing, if only someone would hire me for that.)

But the play! This play—having John Guare’s dialogue in my mouth again—it’s like biting down on a tuning fork. Painfully resonant. It rings in the head. You feel it in your jaws. Speaking of the young con artist who’s convinced her and her husband that he’s the son of Sidney Poitier, Ouisa says, “We turn him into an anecdote . . . ‘Oh, tell the one about that boy.’ And we become these human jukeboxes spitting out these anecdotes to dine out on like we’re doing right now. Well, I will not turn him into an anecdote, it was an experience.”

Human jukeboxes, spitting out anecdotes. It seemed to me, when I was young and had reached critical mass on the repetition of wartime stories, that Margo and Frankie were caught in a loop, reliving and reciting those glory days over and over. Put another nickel in the nickelodeon, out comes the story of Ole 99, the story of the Swoose—all that Greatest Generation lore—over and over until the war stories became as mundanely rote as the fruitcakes and aquacades and Gigi’s goiter. What did it even mean anymore? What had it meant in the first place?

“There I was in Okinawa with nothing between me and the cold, hard ground but one thin nurse.”

I will not turn him into an anecdote. It was an experience.

Luzon Island, 1941

Pearl Harbor was attacked before dawn, Philippine time, and Manila radio soon blared the news. That was what Frank awakened to, danger jerking him by the shoulder, shouting harshly in his ear, jerking him to the double quick.

Men at Clark Field who had been on the alert now for three weeks, tense, ready for whatever action, gulped breakfast and ran for duty, questions and orders crackling the air like static grown to explosions.

Is it rumor? A suicidal “incident?” The real thing—war?

Stop the camouflaging job on Ole 99—too late for that now. Load bombs. Keep the engines warmed up. Halt the bomb loading. Unload. Take on cameras for reconnaissance. Keep the engines warmed up. The news is true. It’s war. The Japanese will try to strike here—don’t know when, but it will come. Cameras ready? Go on with the camouflage. Engines ready. Wait for orders.

With Frank in the operations tent and the Ole 99’s crew standing by her, ready to start the great engines—it hit.

Japanese bombers roared over, a black V and then another, and more zooming behind them. There was nothing to do but take it. Frank lay with two others in a foxhole for one, and took the ruin that seventy Japanese bombers could hurl on an easy target. In the sudden eternity of a few seconds—a roaring thunder, piercing screaming whistles downward, a grinding quaking shrilling roar. The ground he was lying in pitched and heaved and quivered.

The thunder roared away to nothing, and the earth shuddered to stillness except the crackling of our planes burning. Then a hum. More planes. Fighter planes—our own, the men thought, and straightened to watch. The fighters swooped in low, with orange suns on their wings.

This time Frank dived into a big ditch with about forty others—another man collapsed into it, streaming blood, and died. The attackers, strafing with machine guns and cannons, tore over the field, circled, returned, again and again. Gunshot spraying the edge of the ditch. Burning planes crackling. Gas tanks gone, with hissing and shattering explosion. One Fortress near the ditch being systematically shot to bits. Mission accomplished.

Frank walked past the ruined plane, across the bomb-dug field, past more burned planes, scorching with the heat of their burning. Then over the crest of a runway toward 99, hurrying to see—

The twisted, crumpled, blackened skeleton of our plane. Four men, burned, under the plane. The crew lying on the other side of her, eight of them, sprawled in a crooked line, one by one where each was struck as they ran toward shelter: boys Frank had worked with and lived with and depended on for his life; our boys whom he had kidded and cussed and bucked up—lying dead by their twisted ship.

And they were still so much themselves, and after the first moments, Frank walked to the farthest one, Tex, his copilot, and lifted him in his arms and talked to him. He talked to each one, somehow, slowly, puzzling with them how this terrible thing could have happened, talking it to them over and over, reaching to pillow them with something, some kind of sense in this utterly senseless horror, and telling them this couldn’t be the end—whatever it took, we’d fight on and win, and Ole 99 somehow would be making the long flight, too, with all of us.

“Life,” said Truman Capote, “is a moderately good play with a badly written third act.”

This proved agonizingly true for Frankie. But if it hadn’t, I might not have known how to go about rewriting Margo’s third act. Or my own. That’s how I’m able to live with mistakes that were made.

My father’s last five years passed so swiftly. That time comes back to me now as an intense blur of work, play, accomplishment and airplane food. Through most of it, Frankie was going strong, still rocking that bow tie and motivating crowds for General Tel. Health conscious and fit throughout his life, he kept himself in condition as a point of honor. Now in his eighties, he could still dance, do handstands and drive like the wind. He refused to give in to the advance of gray in his receding hairline. The same colorist who kept me vibrantly red used to do his roots. Afterward, he’d stand and grin and declare, “I’m a new girl!”

It was harder to mask the cracks that began to appear in his mental and physical infrastructure. I see now that during those years, he must have been devoting a tremendous amount of energy to keeping up the heroic construct that had defined him all his life—and had, to a great extent, defined Margo, whose identity was so intricately woven with his. I saw my father as an immovable object; he saw me as an unstoppable force. For most of my life, that dynamic worked in my favor because Frankie and I shared common ground and goals, but Frankie and I could come to blows in a way I haven’t with anyone else in my life—probably because I’ve never known anyone else who was so like me.

When I decamped to my parents’ home in Toluca Lake where I would live while Sisters was being filmed at Warner Brothers, Frankie and I began to suffer something a friend of mine calls “proximity burn”—a series of small annoyances that are individually no big deal but collectively begin to chafe. This house was fairly small and seemed to be getting smaller by the day.

“Frankie.” As I sat in my room, trying to learn lines with my hands cupped over my ears. “Do you have to have the TV at top volume all the time?”

“Frankie.” As I walked in the door to find a porn video playing. “For God’s sake. Must you?”

“Frankie.” As I white-knuckled the passenger seat of his car. “It’s not an airplane. You can’t bank around the corners like that.”

Because I was home so little, we managed to keep a lid on things (with Margo gently interceding as needed) for the first two years, but the driving issue slowly escalated from a simmer to a rapid boil. Frankie had always driven like a fighter pilot: skillful and dynamic with a serious need for speed. He did not respond well to criticism (to put it mildly), but I was certain my employers at Lorimar would not respond well to my face going through a windshield. How were we to tell this legendary flyer that he was losing his mojo?

Eventually, we would have to sit him down intervention style and take the keys away, but for the moment, Margo and I returned to the slow simmer when Frankie grudgingly agreed to trade in his eight-cylinder gunboat for a smaller car with less horsepower. Honestly, I don’t think Margo was ready to give up on Frankie’s reassuring presence in the driver’s seat. We were used to being chauffeured and facilitated by our hero, and facilitating his self-denial was little enough for him to ask of us in return.

After the third season of Sisters, I did buy my own house (for those gentle readers who are thinking, Why the hell doesn’t she buy her own house already?), but it was empty and needed work before I could move in, and at the end of every fifteen-hour day, I was grateful to go home to people who loved me, even if we did occasionally drive each other crazy. Frankie and Margo were still my greatest allies and trusted advisors—and never once did either of them say, “Swoose, wake up and smell the eviction notice.” They liked having me there, and I liked being there. It wasn’t exactly the quintessence of Hollywood glamour, but I was never about the trappings of success. The greatest luxury I could imagine was to spend every ounce of my energy working a fifteen-hour day, crash on the foldout bed in my old room and fall asleep over my homework, studying lines for the new day that was scheduled to begin in a few hours.

We had running jokes about “You know your call is too early when . . .”

“. . . the moon is still up when you’re driving to work.”

“. . . yesterday’s hairspray has yet to wear off.”

Frankie had the best one, a souvenir of his flying days: “The last thing I did before bed at night was get up in the morning.”

Filming a television series (if not as life-threatening) can be equally life swallowing. The pesky problem of what to do on a Friday night is solved; you’re usually shooting straight on through till dawn on Saturday.

I was the veteran of the Sistershood, number one on the call sheet, and while that didn’t endow me with any particular responsibility or privilege, I liked feeling like the Big Sister. I prefer a jerk-free environment when I work and wanted the tone on the set to be about kindness, collaboration and a strong work ethic. I hoped my younger sisters would look to me for that, the way we all looked to Goldie to set the tone of happy productivity on the set of Wildcats.

Patricia, Sela, Julianne and I fell into step right away and became very close. We were acutely appreciative every time the show was picked up, and while we always hoped we’d be picked up again, we never took it for granted. More important, we didn’t take each other for granted.

Julianne introduced us to a favorite restaurant in Brentwood, and that became our Saturday night haunt—our version of the Reed sisters’ steam room, I suppose—where we talked girl talk, laughed until we cried (and sometimes cried until we laughed), and bonded over a single Death By Chocolate served with four forks and a round of vodka martinis. Julianne is generous, guileless and sweet, one of those people who’s good to everyone around her and hard on herself, on the Stairmaster every morning before dawn, working hard at not being the baby of the family. Patricia is wicked smart with a sharp sense of humor and a New York sensibility—which in combination with her prowess as a mom would, in my humble opinion, make her a great director. Sela had started out as a successful model, so I used to tease her, “I thought I was gorgeous when I was in the makeup chair, but then I walked onto the set and remembered—shit, Sela works here.”

People tend to project brotherhood when they see an ensemble of men, but they look at an ensemble of women and expect diva trips and cat fights. I won’t pretend that never happens, but it’s the exception, not the rule, and it didn’t happen here. Toward the very end, there was some of the aforementioned proximity burn, but I can honestly say that the four of us started as friends and parted six years later as sisters. Here again, I wish I could accommodate the tabloids with some sexy mudslinging, but these disobligingly good women provided me with nothing salacious to report. It may fly in the face of conventional wisdom, but the truth is, beautiful women can be smart, and smart women can be kind, and a sisterhood can be as decent and compelling as a band of brothers.

A movable feast of supporting characters came and went over the years. Ashley Judd played my daughter and was a darling soul, mature and savvy beyond her years. (I wish I’d had that strong sense of self when I was starting out.) Paul Rudd came on as her husband, and (to my horror) I found myself playing a spectacularly menopausal grandmother, complete with hot-flash-simulating special effects. George Clooney was with us when he was still an undiscovered natural wonder—a dreamboat who knew he was funny enough to get away with just about anything. (Is there anything sexier than the dreamboat/funny/occasional smartass combination?) Robert Klein came in to play my husband (the tax evader, not the cross-dresser), and I developed a serious crush on him. If ever a straight man could make me forget Nathan Lane, it would be Robert Klein. I laugh harder and think more during dinner with him than I do during The Colbert Report.

Filming an hour-long show every week demands a tremendous time commitment from everyone involved, but with Frankie and Margo’s tactical support, I was able to keep up the mad pace I thrive on, accepting theatre gigs and movie roles during every hiatus and sometimes even while we were shooting. During our first hiatus, I did Terrence McNally’s Lips Together, Teeth Apart with Nathan Lane at the Manhattan Theatre Club, a wonderful way to be reunited with Christine Baranski. While we were filming our second season, I did And the Band Played On for HBO—a gratifying gift of a role that took only one day but meant so much to me. I also did The Positively True Adventures of the Alleged Texas Cheerleader-Murdering Mom, with Holly Hunter and Beau Bridges, a gloriously fun film with the smart edge I love. They accommodated my Sisters schedule by packing three weeks of work into a few seventeen-hour marathon days.

In 1993, Margo’s sister Mici died, which was sad for all of us, but particularly hard on Margo. I tried to find time for her, but she understood that time was hard to come by. She went out of her way to make me feel free to leave, and I went out of my way to take her with me whenever I could. It made our lives immeasurably easier when Perry joined us. He’d been running a health food store in Laguna and bonded with Mici, who came to depend on him during the last years of her life. He was more than a trusted friend; he was her ally and aide-de-camp. It’s hard to précis Perry’s job description in ten thousand words or less: troubleshooter, office manager, domestic partner, travel cohort, colorist, archivist, accomplice, confidante, spin doctor, inertia disturber, dog wrangler.

There was a time when, if I needed someone to run interference for me on the phone, run errands for me while I worked late or run lines with me when I was cramming, I did what Frankie had always done: I depended on Margo. Perry stepped into her shoes somewhat, bringing a good soul and calming influence as friction between Frankie and me increased along with his need for Margo’s attention.

In 1994, I had the opportunity to work with Katharine Hepburn on One Christmas, a TV movie adapted from a trio of short stories by Truman Capote. I initially turned it down, telling my agent, “It’s impossible.” But when I mentioned it to the makeup artist on the Sisters set that day, he rousted me bodily from the chair and said, “Call him back! Get out of this chair, call back right now, and say you’ll do it. Are you insane?” I immediately came to my senses: this was overwhelmingly likely to be Katharine Hepburn’s last film. Of course, of course, I had to do it. And conveniently, I knew someone who’d been making impossible things possible from the time he was a teenager.

“Frankie.” It felt good to both of us when I turned to him for help. “Logistics issue. How can I commute between L.A. and North Carolina for a month or so?”

Truman Capote’s One Christmas (1994). I was incredibly honored to be with Katharine Hepburn in the last scene she performed on film.

NBC/NBC UNIVERSAL/GETTY IMAGES

He called in the sort of favor only flyers can call in. Two or three times a week, I bounded off the Sisters set at ten o’clock. Frankie was waiting for me in the car, and we sped to the airport in Burbank where the pilot, Frankie’s friend Clay Lacy, was pushing the time limit for takeoff. We flew away, leaving Frankie waving on the tarmac, the same way he used to fly away like a kite on Margo’s string. We’d lift off under the stars and drop by Texas for fuel somewhere in the night. I’d wake up in North Carolina (nothing could be finer) in the morning. I’d sprint to the hotel for a quick shower and haul it to the set to get into my meticulously tailored 1930s suits, hair and makeup.

Every day was packed with activity, because they knew I’d have to leave again that night or early the next morning. Clay and his copilot were waiting to fly back to L.A. and deposit me as the sun rose in Burbank, where Frankie was waiting to take me to Warner Brothers so I could start another day on the Sisters set. Sela and I were both nominated for Emmys that year, and Sela won, but before I had a chance to stew about it, I was back on an airplane to go make a movie with Katharine Hepburn, which goes a long way toward consoling a girl.

People shook their heads with a mix of awe and apprehension, but I felt energized and exhilarated. Frankie felt heroic again. (I felt a bit heroic myself a few times.) Margo kept us all blissfully on the tight schedule. This was the three of us at our level best.

In the last scene Katharine Hepburn would do on film, she and I are perched on a bronze brocade settee. “I’ve had a life of no regrets,” she says, “and that’s what I wish for you, my dear. A life with no regrets.”

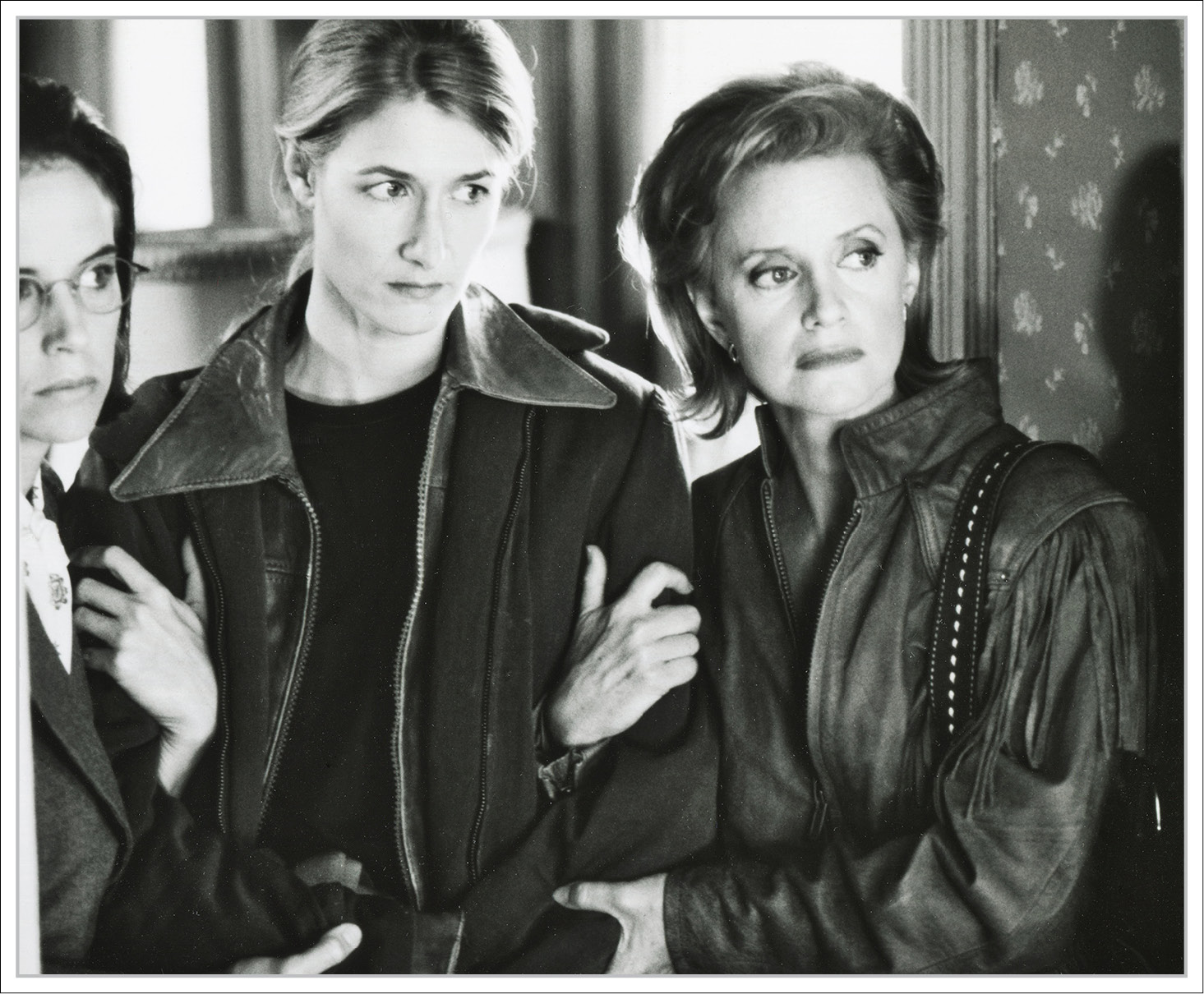

With Kelly Preston and Laura Dern in Alexander Payne’s Citizen Ruth in 1995.

MIRAMAX FILMS/KIMBERLY WRIGHT

A year later, during the hiatus before our last season on Sisters, I did an indie film called Citizen Ruth, written and directed by Alexander Payne (who later did Sideways and The Descendants) with Kelly Preston and me as militant lesbian partners, Laura Dern as a pregnant, confused, chemically dependent runaway, Mary Kay Place as our clinic-protesting adversary, and Tippi Hedren and Burt Reynolds as two Titans at the center of a pro-choice/pro-life controversy. One would not think it remotely sensible to attempt high camp comedy about abortion, but Citizen Ruth manages that while making a rather profound statement that caters to no political agenda and leaves neither side unscathed. The script was intelligently hilarious, and Alexander Payne is from Omaha, where we’d be shooting on location.

The shoot was grueling, especially for Laura, who was fearless and egoless and game every step of the way. The farmhouse where most of the action took place was freezing cold because all the electricity was devoted to sound cables, lights and consoles. Torrential rains created a sea of mud between the house and the no-frills trailers and craft service tent, where we ate grayish chicken thighs and broccoli stems almost every day. It could have been a misery, but it wasn’t. It was fun, and the movie is unlike any other movie I’ve ever done—or seen for that matter. It’s one of those unique creative projects, like Pushing Daisies and Cheerleader-Murdering Mom, where the script is the star. Roger Ebert praised its “reckless courage”; it ruffled some feathers, for obvious reasons, but I was proud to be in it.

While we were shooting, Frankie happened to be in Omaha for the annual meeting of Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, and we went to dinner at a local restaurant. When we first sat down, I was distracted, shifting gears after a long day on the waterlogged set. One of the producers stopped by our table, and as I introduced Frankie and the two of them chatted for a moment, I was stricken by the realization that something was wrong. Not rush-to-the-emergency-room wrong or even go-back-to-your-hotel-room-and-lie-down wrong. But distinctly off. It was like looking at the vacant farmhouse, strangely at sea on a muddy swale, drained of its electricity, fogged in and fragile.

During the labored conversation, it was impossible to ignore the subtle shift in Frankie’s personality or the more obvious gaps in memory and articulation. That night, I lay in the dark feeling sad and mystified. I tried to talk to Margo, but she did what she always did where Frankie was concerned; she kept up the brave face, assuring me everything was fine, changing the subject like a magpie moving on to the next shiny object. By the time I got home, my sadness had crystallized to a fear-based, childish anger. How dare he be vulnerable like that? How dare he change, as if I no longer needed him to be Frankie? This was not just some ordinary old man. This was the larger-than-life father under whose broad steel wings I’d been born, the majordomo that’s known as the honcho hippo.

When I returned to work for the final season of Sisters, I could feel the drift in my on-set family as well. We’d run our course, and it was such a good run, but contracts were coming to an end, and we were all getting restless, ready to move on. I’d been well used, and this show had given me so much. I was certain my sisters felt the same way, and I hoped that we would forgive each other for those moments when battle fatigue got the better of us. We all have moments when we see our sand castles crumbling, and we get a bit graspy, which can be as unbecoming as it is futile.

As the show drew to a close, articles were written about the groundbreaking subject matter we’d covered, the awards and nominations for acting, writing and editing, how the complexity of the characters had evolved and the significance of this show in the overarching genre of television drama. Patricia and I wondered wryly where all that laudation was when we really needed it—back in season two, when we were hanging by a thread and being dismissed as a Harlequin romance with tampon commercials.

Something I know because I grew up moving constantly: you learn, as a survival mechanism, to separate from the places you love best. The moment you know you’re leaving, there’s a devious little spin doctor on your shoulder, whispering, “It’s for the best. This place sucks.” And your need to feel okay about moving on begins to fill in the blanks, grasping every irritating detail, no matter how small, planting them like grains of sand in your shoe so that by the time you have to say good-bye, you’ve convinced yourself that what you feel is relief instead of grieving—until later on, when the grieving eventually demands its due. (Multiply that dynamic times ten thousand when applied to separating from people you love.)

At the end of the day, we were a family. We rose up for each other when someone was having a bad day. We pulled together—even through difficulties and the intrinsically competitive environment of the industry—to do the work that would only work if we did it together. It was a sob fest shooting the last scene. A major part of our lives was coming to a close.

The pace after the show wrapped was more relentless than ever, because now I was searching for a steady succession of smaller jobs to replace this one huge job, and Frankie, whom I’d always depended on for moral support and a strong sounding board, was the opposite of all that. During the last year or so of Sisters, the terrifying change in his personality progressed, circling tighter and darker until he was an absent, angry stranger who flew into a rage over everything and nothing. It was impossible to reason with him, impossible to ignore him, impossible to have a conversation with him, impossible for him to sit quietly.

He’d always been fastidious about personal grooming and hygiene, but now he entered a gray area where he was no longer handling it properly but angrily rejected the slightest insinuation that he might be slipping. If Margo or I gently inquired, “Frankie, do you need to visit the bathroom?” his embarrassment would instantly touch off a brush fire of indignant wrath. He was enraged that we would insult him so, that we would even suggest he was forgetting himself in some vital personal way. What kind of idiots—

Margo and I didn’t know how to bring in help when Frankie was so vehemently opposed to it, and the two of us were not emotionally or physically equipped to handle him, because he was not about to be handled by us or anyone else. After a series of upsetting incidents, the situation breached one evening when I found feces smeared across the walls in the hallway. In less than a moment, Frankie and I were engaged in a horrific screaming match. What the hell is wrong with you don’t you even with me what the hell is why why why would you where do you get off accusing even know what don’t you fucking talk to me like can’t deal with your shit you know goddamn well I did not then who did it nothing to do with—and more meaningless word storm. I wrenched a knife out of the block and cast it in the sink, not knowing if I wanted to stick it in his arm or my own.

“This is insane, this is insane.” I covered my face with my hands, wrecked and winded, clinging to the edge of a cliff. Margo stood between us, trying to keep things from escalating. I wheeled on her and said, “It’s him or me, Margo. I don’t want to leave you here alone with him, but I cannot do this anymore.”

Not knowing how to respond, Margo pulled into herself like a little box turtle. Lacking any coherent input from me or the honcho hippo, she flailed for the best solution she could think of and made the decision to move Frankie to a nearby rental house they owned. By nightfall the following day, she’d installed him there with comfortable furnishings, his favorite chair, and a TV he could blast to his heart’s content.

“So I’ve been exiled,” he said bitterly.

Margo begged him not to think of it that way.

“Put out to pasture then.”

“Frankie. You’ll see. It’ll be better this way,” I said. “We can all take a deep breath and figure out what’s best for everyone. We can talk about it later. When I get back. I have to go, but if you need—”

“I don’t.”

“Okay. Well. I need to get some sleep.”

Margo and I closed the door and walked home in the dark and cried in the resounding quiet. This wasn’t how anyone wanted this to be, but no one had ever brought up the subject of how we did want it to be. We were completely open with each other about so many things. I’d seen my parents naked as a child. I’d heard them fight and make up. They were well acquainted with all my personal and professional affairs. We had shared happiness and heartache of all the usual varieties. I could have asked Frankie and Margo anything, but it never even occurred to me to ask, How does this story end?

One morning he fell and struck the back of his head, and the injury was serious enough that the choice was made for us; he could never be left alone again. He was forced to allow full-time caregivers to come in. We found two male aids who were strong and dependable and willing to tag team in twelve-hour shifts. Frankie settled into an unhappy but functional stasis. Margo was deeply sad but remained tragically chipper, as if she was on a war-bond drive. Perry was Mr. Indispensable, my eyes and right hand at both houses while I was away on location. I felt rotten about the whole thing, but I did what I always had done, sunny skies or gray: I worked.

I went to Vancouver to do a remake of Harvey, which should have been better than it was. The script is classic. The director was a legendary Playhouse 90 alumnus. My costars were funny, funny men. It didn’t air and didn’t air, and finally did air, buried in some under-the-cellar time slot. Which was a mercy. Frankie and I watched it together, and I told him, “I knew it was slow, but I didn’t know it was that slow. Now I understand why they didn’t want it to see the light of day.”

Next box on the flow chart: playing the divorce attorney who goes up against the honesty-impaired Jim Carrey in Liar, Liar. This was a pretty beefy role in the original script, but while we were shooting in the courtroom, the director pulled me aside and told me that some of my scenes were being cut. I could make excuses, I suppose—the situation at home, the fact that I was exhausted because I was also shooting a TV show in front of a live audience that week. Bottom line, I was feeling a bit sullen and not “giving good set,” as we say, which is very unlike me and impossible to maintain when you’re on the set with someone like Jim.

So we were doing take after take of a heated little face-off:

HIM (TO MEG TILLY): “Now, let’s see. Weight . . . 105? Yeah. In your bra.”

ME: “Your honor, I object!”

HIM: “You would.”

ME: “Bastard!”

HIM: “Hag!”

We experimented with a variety of invectives.

“Hog!”

“Cow!”

“Hack!”

“Jezebel!”

Makeup people stepped in to blot us down, and the director, Tom Shadyac, came over and whispered in my ear. We started the next take:

JIM: “Weight . . . 105? Yeah. In your bra.”

ME: “Your honor, I object!”

JIM: “You would.”

ME: “Overactor!”

And then we were all howling with laughter, including Jim, who threw his arms around me. They ended up including this moment in a montage of outtakes during the end credits, and to this day, it’s what people remember most about my part in this movie. They shout out to me on the street: “Overactor!” Anyway, I’m certain there’s a metaphor there. Something about the unscripted moments in life and the efficacy of being able to laugh at oneself, or perhaps it’s as simple as “What goes around comes around.” I didn’t have time to process it at the time; I had to sprint back to the TV series—a short-lived sitcom called Party Girl with Christine Taylor, who’s terrific, but the show was one of those confections that seems to have the right ingredients until it falls flat in the oven.

I also had a recurring role on Suddenly Susan, playing Brooke Shields’s mother, and I was happy to be called in for that because I so enjoy being around her. She has a philosophical survivor’s-eye-view of life and the industry, so we laugh a lot, exchanging our war stories. Brooke told me she did an audition where she came in, set her purse down, read the scene. They said great and they’d be in touch, but as she got to the door, one of the producers said, “God bless you.”

“I knew I’d never hear from them again,” she said.

“I’ve learned over the years that I’m screwed if they say, ‘You’re a brilliant actress,’” I said. “It’s like they’re giving me a little something to take with me. Like a game show where they send the loser off with a lovely parting gift.”

I told her about a movie with Jane Fonda and Robert De Niro—Stanley & Iris—which was quite a meaty role when it was offered to me. I played Jane’s sister in the accidentally prophetic script about family members crammed into a small house, driving each other crazy. It was written by Harriet Frank Jr. and Irving Ravetch, who’d written Norma Rae, so expectations were high, even some dare to dream about the Oscars. We were rehearsing in Connecticut, and late one night, while I was out for a brisk walk around the chilly parking lot, I came upon Irving, who was also taking the evening air.

We greeted each other, and he said, “Great work today.”

“Thanks,” I said. “Great scenes.”

And then he said, “Just remember, whatever happens . . . you’re great.”

I instantly knew I was hearing the hiss of the guillotine right before my head rolled across the cutting room floor.

“Ultimately,” I said to Brooke, “there’s no good way to be told something you don’t want to hear.”

Another accidental prophesy.

In October 1996, I was in L.A., shooting a Lifetime movie called Little Girls in Pretty Boxes. Coming home from the set at dusk on Halloween, I carefully wove through the neighborhood. The streets were busy with trick-or-treaters, the sidewalks bobbing with flashlights. Suddenly Susan was scheduled to be aired that night, and I was hoping I’d get home in time to see it.

As I pulled into the driveway, I saw my manager waiting for me, and because I am the daughter of Frankie and Margo Kurtz, I felt an optimistic surge of excitement. I thought, “He must have great news! He came all the way over to tell me in person.” But then I drew close enough to see the expression on his face.

I ran toward him across the yard, saying, “Oh, God—not Margo! Not Margo!”

He shook his head. “Frankie.”

“And when that happens, I know it,” Truman Capote wrote at the end of his lovely Christmas story. “A message saying so merely confirms a piece of news some secret vein had already received, severing from me an irreplaceable part of myself, letting it loose like a kite on a broken string.”