CHAPTER TWO

Descendants of Art and Grace

Margo and I have been singing the same duet for years.

“My sweetheart’s a mule in the mine. I drive her with only one line, And as upon her I sit, Tobacco I spit, All over my sweetheart’s behind!”

She’s lying in the stirrups at the urologist’s office, and he is doing something unnamable to her urethra. She grips my hand, and I launch into verse two.

“My sweetheart’s a mule in the mines, way down where the sun never shines. That’s appropriate for the occasion, isn’t it, Mommie?”

The urologist smiles at us from between Margo’s knees but doesn’t pause in his task. It’s one of those “do whatcha gotta do” days all the way around. My part is to stay calm, provide entertainment and hold her hand against my cheek. The infrastructure from wrist to knuckles feels as fragile and weightless as the brittle armor left by the passing of a cicada.

“I have the skeleton of an autumn leaf,” she recently told a friend.

In general, Margo’s quite good-humored about the indignities that have come with her decline and always grateful to the caregivers who manage to do what needs to be done while making her feel respected and loved. There’s a point at which private bodily functions become acceptable conversation again, just like they are when there’s a baby in the house. Between toddlerhood and old age, we have the luxury of having everyone ignore the tone and timing of our wind passings and tummy functions, but a healthy bowel movement in the proper receptacle is cause for celebration when you’ve experienced a few of the unpleasant alternatives.

She doesn’t complain, but now and then, she shows signs of wear. During a recent “serial enema” (the term itself is an appalling reminder of Bette Davis’s assertion that “old age ain’t no place for sissies”), Margo said to the nurse, “Darling, I love your work, but I’m not sure how much more I can take.”

In general, Margo was always a progressive and good-humored pragmatist when it came to her personal health. (Her mother was the same. I remember my grandma Gigi quipping about feeling “half-assed” after her colostomy.) During the early years of their marriage, Margo and Frankie had hoped and tried, but years went by, and she didn’t get pregnant. Quite ahead of her time, Margo refused to be discouraged. In a day and age when women were trained not to question their family practitioner, she researched the science and went from one doctor to the next until she found a fertility specialist.

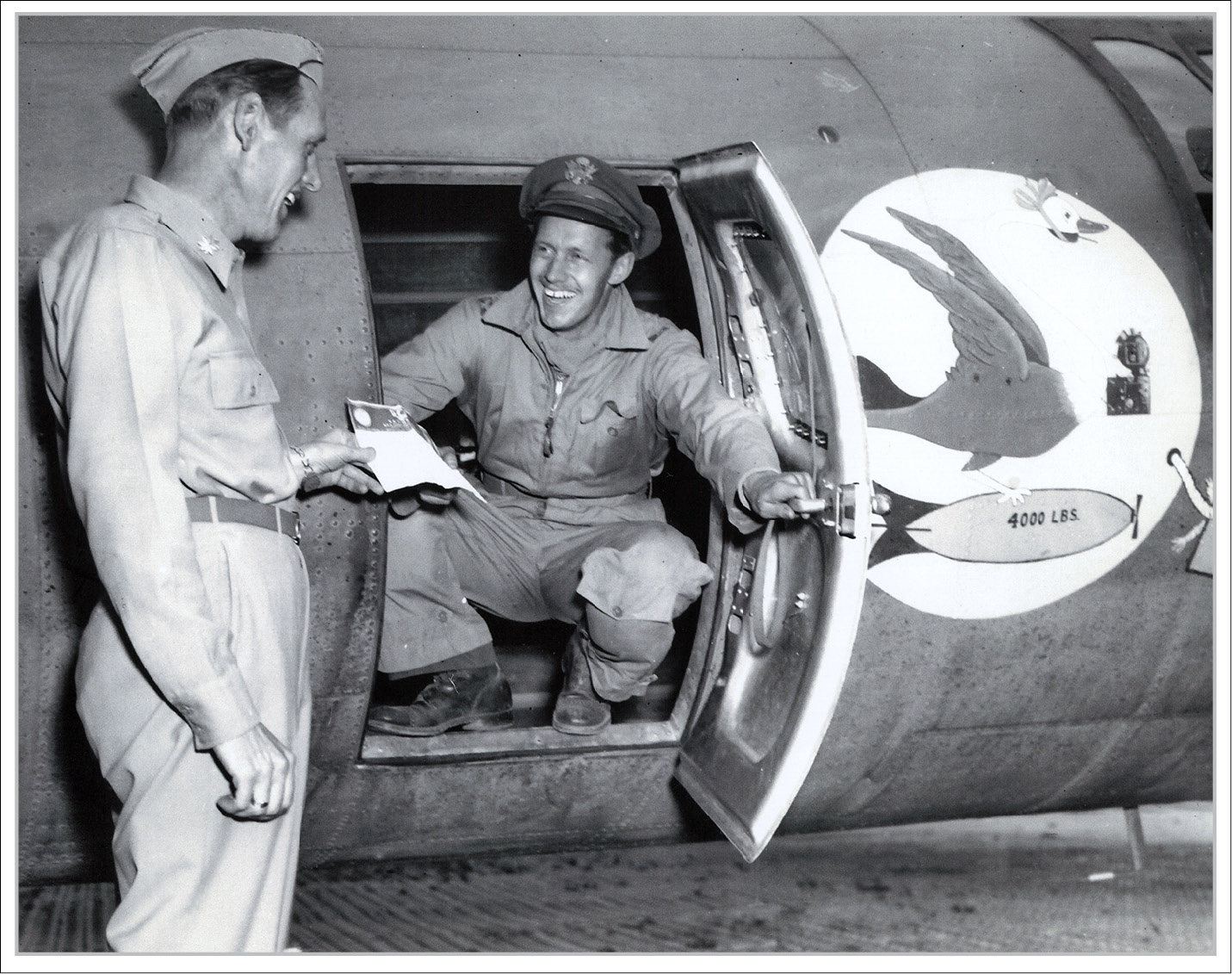

Frankie receives the happy news of my arrival on board the Swoose in Italy, September 1944. But Margo forgot to mention one small detail. (It’s a girl!)

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

They found out I was on the way just before Frankie left for the European Theater. He spent the summer flying missions out of Italy, I think. I can’t recite the timeline chapter and verse, but it was a grueling stretch during which Frankie and his comrades pushed through airspace, strafing and bombing a pathway for ground forces, mile by mile and at great cost, while Hitler and Mussolini slaughtered Jews, gypsies and resistance fighters below.

They started at two in the morning, Margo wrote later, with the briefings for the day’s mission. Next the long flights over enemy land through skies set with traps of death, then back to the base and the time to turn an exhausted body and anxious mind to the hours at his desk, administrative duties, trips to higher headquarters, and finally, the effort to grab a few hours of sleep before another mission would begin . . .

He had seen so much death today, he couldn’t imagine a birth.

On a bright September afternoon in 1944, as Frankie climbed wearily from the cockpit, he was handed this telegram:

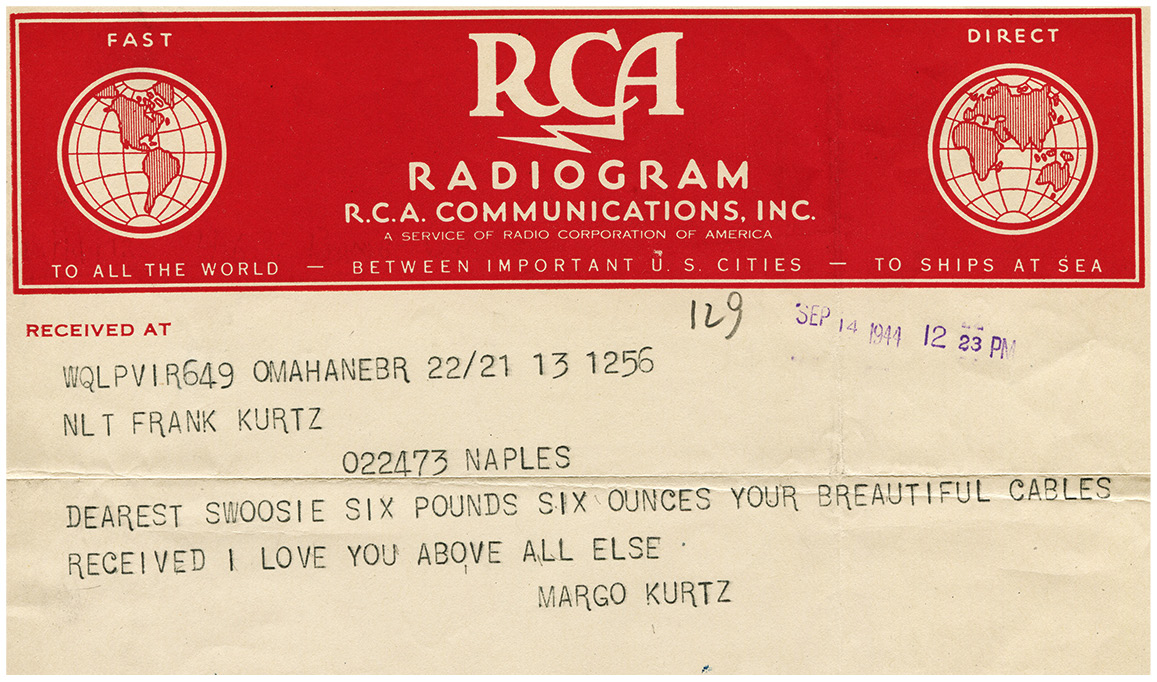

DEAREST SWOOSIE SIX POUNDS SIX OUNCES YOUR BEAUTIFUL CABLES RECEIVED I LOVE YOU ABOVE ALL ELSE

MARGO KURTZ

According to family lore, Charlie, the machine gunner, clapped Frankie on the back and said, “I’m going to write Red and Danny the news. I’ll tell them you finally managed to do something without our help.”

Frankie carefully folded the telegram away in his flight papers. When I found it in a box of papers and press clippings after Margo came to live with me, I was so grateful that it had been informally but lovingly archived. Oh, I do love that telegram, love that she made room for the words above all else in the scant 106 characters (thirty-four less than one is allowed on Twitter): Forget the punctuation, but don’t spare the poetry. That is classic Margoism.

Unfortunately, she neglected to mention whether their Swoosie was a boy or a girl, so Frankie dangled in suspense for another two days, happy but subdued by the gravity of this new assignment: fatherhood.

There are several apocryphal tales circulating about how I came to be named Swoosie. The Associated Press reported that I was christened Margo Junior and nicknamed Swoosie at the suggestion of an AP reporter at the hospital. Margo indulged that, but it’s clear from letters and accounts in both her books that she and Frankie intended all along to call me Swoosie. My birth certificate says Swoosie. I have no memory of ever being called Margo Junior, and I certainly never felt pressured to be her Mini Me.

The rote “How I Came to Be Named Swoosie” explanation I learned to recite as early as I could recite the alphabet: “I was named after a B-17 my father flew during the War.”

Looks fairly terse on paper, I see now, but I tried on various versions over the years, adjusting for length, pithiness and situational impact. At the end of the day, brevity is the soul of wit, isn’t it? Keep it concise. Tweak delivery as appropriate for the audience. The backstory about how the namesake of my namesake was the subject of a Kay Kyser song, “Alexander the Swoose,” or the wrap-up component about the Swoose ending up in the Smithsonian—why go there? I held all that on reserve for the inevitable Q&A period that always followed introductions:

“Was your little sister not able to pronounce Susie?”

“What nationality is that?”

“Were your parents drunk?”

Other FAQs ranged from eastern European lineage to good-luck charm.

Apparently, my parents—sober or not—were the only two people in the entire Sally-Mary-Ethel-oriented universe who thought Swoosie was a proper name for a person. It was repeatedly made clear to me that they were mistaken and that Swoosie was, in fact, a ridiculous name, which I came to hate. I hated having to repeat it at social gatherings and spell it out every year on the first day of school. Hated the raised eyebrows and suppressed snickers. Hated how everyone from the playground to the Emmy Awards consistently mispronounced it, rhyming it with “woozy” and “floozy” instead of “juicy” and “you see.”

“Swoosie,” one of my many elementary school teachers enunciated. “Are you sure, dear?”

And for a terrible moment, I wasn’t! For a moment, it actually seemed more logical to me that this name was the silly invention of my childish mind rather than a carefully considered, legally binding decision made by two responsible adults.

“Anything that sets you apart is an advantage,” Margo tried to tell me, and this did prove true later on, during my career, but during my school years, it was agony. Ninety extra seconds as the center of attention feels like a gift on film; that same minute and a half is a prickly eternity in a classroom full of fourth-graders. And as an added bonus (my fellow military brats will testify for me here), I often had more than one first day of school per year as my family relocated, freely and frequently, from one state to another.

I finally embraced the Swoosie of it all when I was about forty. It probably has been an advantage, but more important: I just like it. I can’t really specify a reason or catalyst. Don’t really need to.

“Because it is my name!” cries John Proctor in The Crucible. “Because I may not have another in my life!” That’s reason enough, I suppose. Anyway, somewhere along the line, I evolved into the nostalgic whimsy of it. These days, however, when I say, “I was named after a B-17 my father flew during the War,” I have to specify “World War II” because War with a capital W has been eclipsed by decades of skirmishes and analogies. I clarify it as a “B-17 airplane” because the Swoose is not the newsmaker it was back then when people were seeing her in newsreel footage before the Saturday matinee. Even then, I doubt that people understood what the Swoose meant to my father personally.

Frankie’s company had suffered terrible losses in the Philippines; more than 65 percent of his men were killed at Clark Field two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He’d watched a number of his comrades—his friends—burn to death on the tarmac, and he was forced to leave others behind when he and a strangled remnant of the 19th Bombardment Group eventually managed to escape to Australia. There they salvaged enough parts from an assortment of wrecked B-17s to cobble together a Flying Fortress. The Swoose. She was bulky but elegant with her grafted-on tail and riveted skin, their one chance at survival and only means of salvation. As long as they had her, they could fight back, and in that moment, fighting back was the only way to make those lost lives—and the almost certain loss of their own lives—mean something.

“Those scratches on her running gear were made by sand grains of Wake Island,” it says in Queens Die Proudly. “That little dent on her wing was made by a spent-bomb fragment the day the war began . . . The battle paint on her wings was blistered by the sun in the high skies over Java and nicked by sandstorms over the Australian desert. Of the very few to escape Clark Field, she is the only one to come home.”

California, 1934

When I was very small I was dreadfully afraid of horses. Then one day when I was five years old, my father picked me up and sat me in the saddle on top of a horse. I was as frightened as you would expect. But I stayed, and in time I rode, quite well, and loved it. At nineteen, it was all to do again. One quiet day Frank said: “Margo, I’m going to take you flying next week.”

I was suddenly very dizzy even being only a few inches off the ground in his little open Ford roadster. Fly? Out home in Nebraska I had seen flying circuses. I had seen planes crash. The mere thought of going up in one myself—oh, no!

Less than a week later my shaking body with choking stomach was lifted into the front cockpit of a small green plane. It took off, it gained height; I was sitting on the peak of a pyramid heaved into the sky by a frightful explosion. But then we came above the overcast, and somehow the blindfold which is ignorance was lifted from my eyes, all my senses came to, just newly alive, and I was drinking in the exhilaration, the intoxicating air which only airmen breathe. The small robin who first gets the feel of his wings—what a surprised yet natural confidence! Now I could turn my head and look at Frank in the back cockpit—now I knew I could turn without “upsetting” the plane.

He was smiling, and in the clear blue of these heavens, the message came to me so truly. He was taking me into his life, and this blue sky set the stage of my new horizons, and the story unfolded so naturally. Nothing was a burden now. In this plane I had lifted above the details, the worries and distorted comparisons—had put them in place. There would be no easy routes into these new horizons. But here was my realm, and here my way.

So you see, this isn’t the first time my mother has left the Earth.

Before they were married, my father taught her to fly. I have a photograph of her on the wing of Yankee Boy, the 120-horsepower aircraft in which Frankie—still a teenager—had already begun to make a name for himself as an aviator. Another photo shows her at the beach, lifted high above her brother’s head. Margo’s history is defined by an innate buoyancy that attracted and uplifted everyone around her.

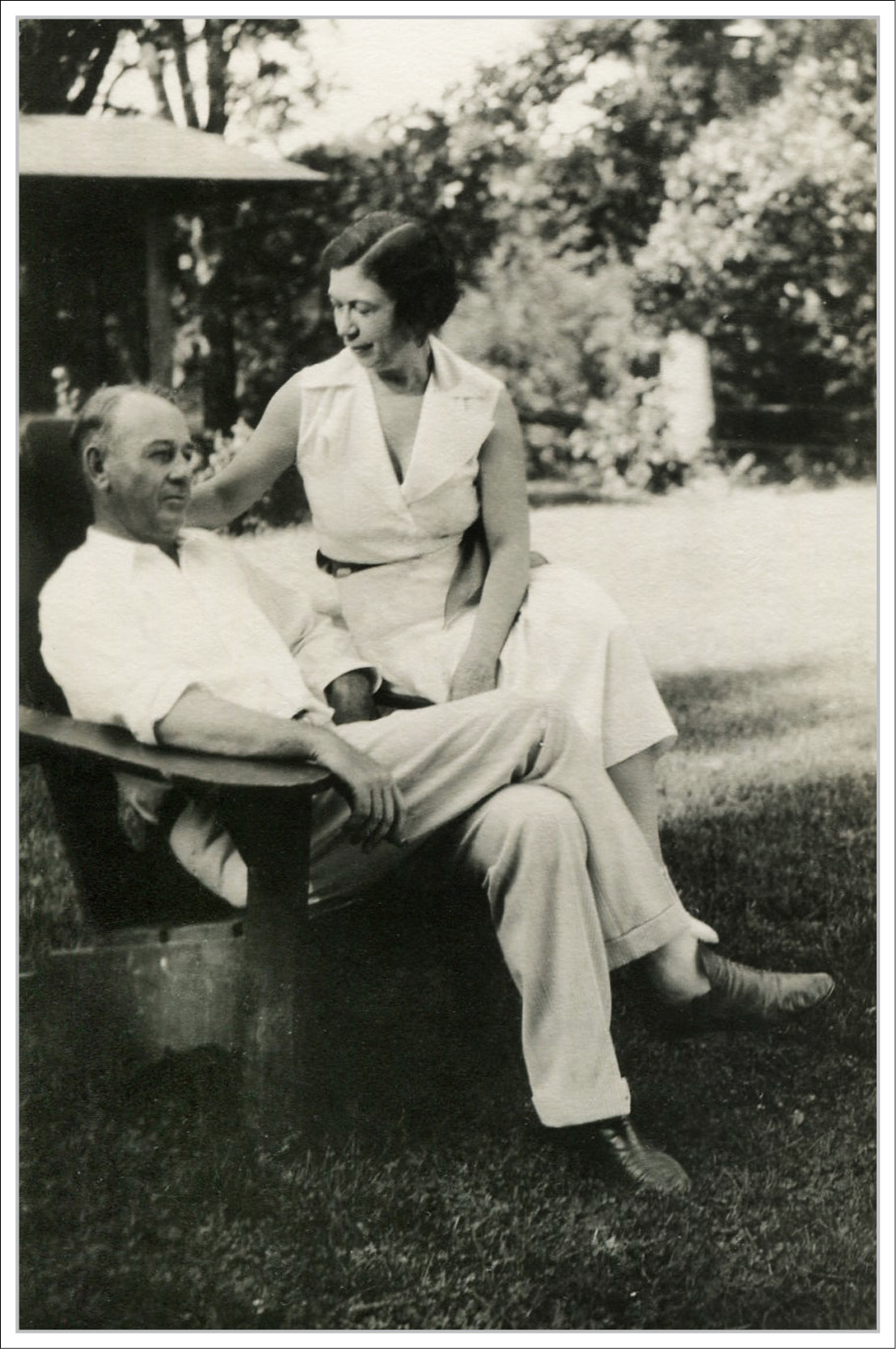

A certain amount of credit for that belongs to my grandparents. Their house in Omaha was the epicenter we circled back to over the years as military life kept us nomadic, and that was good for me, but in the bigger picture, I think it was Daddy Art and Gigi who set the tone of joy, love and acceptance pervasive in my upbringing.

During most of my first year, and off and on through much of my childhood, Frankie was overseas. Often Margo and I stayed with Daddy Art and Gigi, and I stayed with them myself while Margo trooped around the country on book and war-bond tours. Among my earliest memories is the comfortable impression of being on Gigi’s lap, circled in her arms, resting my head on her ample bosom while she played poker, chain-smoked Chesterfields and sipped Early Times bourbon from a tall glass tumbler. It’s a little ironic—or perhaps plain hilarious—that we were being held up as a Good Housekeeping–anointed example of the All-American Family. We were definitely not shaped like one.

My grandparents’ home was a comfortable two-story dwelling in a pleasant but not especially affluent neighborhood. If Omaha were L.A., this would have been Sherman Oaks, not Beverly Hills. Solidly middle class, but rich with stories. Family anecdotes were told and retold with great flare.

Among these was the tale of how my mother was born after Gigi (who had developed tumors, you see, after the birth of Mici, who was six weeks late, weighing in at a comic-strip-hippo-preposterous fourteen pounds) was told by Charlie Mayo of Mayo Clinic fame, “Grace, no more babies,” but lo and behold, when Gigi went back to the Mayo Clinic a few years later for the purpose of a goiter operation, Charlie Mayo said, “Listen, Grace, we can’t do the operation until after the baby is born,” to which Grace replied with a shriek, “Baby! What baby?” loud enough that she was heard clear down the hall by people who are undoubtedly still talking about it.

“So I was an accident,” Margo would say at that point.

“The happiest accident ever,” Gigi would assure her with a squeeze. “And then along came Bob and Homer, so after that, well, I didn’t pay much attention to the Mayo brothers.”

It had to be a goiter. The very word sounded fantastically, exotically grotesque, and whenever I repeated this bit of family lore to an audience of new friends, I made sure they felt every thyroid-constricting throb.

What a great story! Colorful characters—Dr. Mayo was even a celebrity of sorts—hospital drama, building suspense, a mad twist of plot, a happy ending, and that modest hint at the ongoing romance between Daddy Art and Gigi. It’s a great bit of theatre, as all good family anecdotes are, be they comedy or tragedy. I appreciated this as I went on to make my life and living among vibrant storytellers.

Frankie spoke to me very little about his childhood, and after he died, I was stricken by the realization that I’d missed my opportunity to question him about it. It’s not that the subject was verboten; it just didn’t seem to come up. Nothing was missing. There was no void where “his people” belonged, no occasion where their absence was felt. If anything, the two or three isolated side trips we made to visit Frankie’s mother brought into bold relief how intensely estranged they were. I vaguely remember her posing for a few obligatory snapshots, taut-lipped and cool-handed. Some years later, there was a passing mention of her death, but we didn’t go to her funeral.

Back then I knew only a few fragmented particulars about Frankie’s early years. I’d heard something about two stepfathers who beat him with belts, and apparently no one did anything to pursue him when he ran away from home at age ten. There was an anecdote about him selling fruitcakes that year during the holiday season; he wound up living off the stuff because he had nothing else to eat, and that was why, from that Christmas to his last, he couldn’t stand the sight, smell or mention of it.

Frankie related that anecdote as a funny fruitcake story. He was hilarious when he wanted to be, and let’s face it, fruitcake is always good for a laugh, so it was easy to slide by the fact that this was actually a story about a little boy who was hungry and homeless, thumbing rides with strangers, sleeping on athletic club floors, placing a heart-stopping amount of trust in strangers and scratching out his own little hardscrabble existence by dint of wit and industry.

Margo chronicled Frankie’s childhood and diving career in a second book, but it was never published. I didn’t even know about it until eight or ten years ago. She found the manuscript while she was moving or reorganizing or something and told me, “I’m going to do something with this. It needs work, but it’s pretty good.”

I encouraged her, but the weighty tome was well over four hundred pages, typed on that friable old-school typing paper people used after the war. Neither Margo nor I had any idea how something like that would translate technically or artistically to new-school publishing. The manuscript disappeared into the natural tides and eddies of household activity. When it resurfaced not long ago, I waded through it, wishing Margo was still able to answer questions about it.

The opening pages are kind of a treatise on the fact that we never know what to do with our heroes when we’re done with them. After the war, it would seem, Frankie was struggling to figure out where he belonged in the world. Perhaps this book was Margo’s way of helping him put all the embattled elements of his life story in perspective. She flashes back to his preteen years, during which he ran away from home and sold bicycles, magazine subscriptions and newspapers to finance shelter in flophouses and athletic clubs, where he met Johnny Weissmuller and others who mentored him as a diver. He traveled with aquatic exhibitions and “tumbling acts” and began to fly—all by the time he was fifteen.

Employing more spin than a turboprop, Margo let the harsh realities of Frankie’s truncated childhood slip away between the lines and transformed his story into a Fountainhead of idealistic dramalogue: Huck Finn meets Dale Carnegie in one high-diving heroic journey. Kindly strangers and well-heeled benefactors were rendered in fine detail while drunk drivers, deviants and absentee responsible adults were wistfully—even poetically—reduced to little more than a footnote. She devoted minimal typeface to the people who’d abused and neglected little Frankie; they didn’t deserve to be the subject of a sentence any more than he deserved to be the direct object.

I don’t know what my father thought of this book or if he ever even read it. Given his enthusiastic support for Margo’s magazine writing and for My Rival—and given how against nature it was for either of my parents to be discouraged—it seems odd that this second book was tucked in a drawer and never mentioned for fifty years. All I know is that Frankie chose not to share these memories with me, but he was undeniably scarred by his (cough) upbringing. From his perspective, the little boy in Margo’s book probably felt more desperate than spunky, because spunk is an entirely different dynamic when you’re the one schlepping your fruitcakes on the corner of Skid Row and Third.

In later years, Frankie did send money to his mother, but I remember that being done with a trudging sense of obligation—probably the same degree of concern he’d received from her during his childhood. Nothing good or bad was ever said about her as a human being, but her obituary offers a small keyhole. It was sent to Margo and Frankie by one of his older sisters (Vera, I think), who occasionally sent items she’d clipped from the local paper with obsessive precision, leaving not a millimeter of frivolous margin beyond the typeface.

Dora Fenton Kurtz, the obituary reports, died in 1975 at age ninety-five. She’d graduated from Palmer Chiropractic School, married Dr. Frank Kurtz in 1899 and had four children: a boy (deceased), the two sisters and “Col. Frank Kurtz of Los Angeles, who was the most decorated pilot of World War II, being pilot of the historic Boeing Bomber, ‘the Swoose,’ which is now in the Smithsonian Institute. He was also the only male Olympic medal winner to make three U.S. Olympic Diving Teams.”

Daddy Art and Gigi set the tone of joy, love and acceptance pervasive in my upbringing.

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

Not only does Dora’s obituary say more about Frankie than it says about her, it says more about his airplane than it says about her! We’re left to speculate about the story of her life other than a few basic stage directions (“Exit Dr. Kurtz; enter Stepfather One wielding belt.”), but Dora Fenton Kurtz graduated college at a time when less than 3 percent of women went beyond high school. There was a starkly divided highway between motherhood and career. Palmer was the first chiropractic college in the world, and she would have studied with its founder, Dr. D. D. Palmer, who originated chiropractic care as a health science and began a blood feud with allopathic medicine, and doesn’t that make you wonder which kind of doctor Dr. Kurtz was? Were they fierce competitors or ideological enemies? Apparently, there was enough chemistry between them to get her pregnant with four children neither one of them wanted to raise, but not enough to fend off the stepfathers.

No matter how you look at it, Dora’s life was a study in contrarianism, and it seems that Margo’s book did the best possible thing one could have done with all that. Perhaps it was her way of telling Frankie that if the people who should have loved you laded you with issues instead, you have to zip open that emotional baggage, unload the crap and spirit away whatever well-disguised blessings you can extract. If there’s a lesson to be learned or a quality to be mined, you stuff it in your pocket and leave the rest by the side of the road. You stick out your thumb and hope that love comes along to offer you a lift.

Frankie is living proof that we’re allowed to move on from the families that created us and create the families we need. I’ll never know if his childhood was the casualty of a culture war or the product of a moxie-meets-moment; what matters is that he survived it, physically and emotionally, and that it instilled in him the very traits that would empower him to physically and emotionally survive a war. What I take from all of the above is a sense of awe about the depth of love and breadth of caring Frankie was capable of, despite the meager rations he grew up on.

But this is where Margo comes in, and with Margo came Daddy Art and Gigi, who embraced him as their son, and all my mother’s siblings, and all my father’s Band of Brothers. And then came me. There was no lack of love in Frankie’s life, and that—above all else—is what defined my family.

Best-case scenario, one is born into a place of art and grace. Second best: one learns to rise above.

“My father was a remarkable man,” Margo tells Antonio, the beautiful Brazilian man who has arrived to keep watch over her through the night. “We five children, three girls and two boys, we loved Omaha. The kind of really important people all grew up there, so Omaha became famous for what it could offer. And so my father got all of us on board and got us working, and so we all took our place there, and we learned to fly and do other things too. My father wanted his five children to know how to do anything they wanted to do.”

It’s heartening when she gets talkative like this. That old war-bond tour energy lights her eyes. She has a good audience. Perry and Antonio and I listen without patronizing her, nodding and softly commenting once in a while. “Wow. Amazing. That’s very interesting.”

“We all got crazy about flying. And I even learned to fly and had my part around it. I had been flying. I had been flying as a youngster, but I’m one of five children, and we all learned to fly, and we all grew up in Omaha, Nebraska, which is about halfway from here to New York. And we grew up there, but I grew up in Omaha, Nebraska, actually, which is a good place to grow up. It’s good for people my age.”

Candidly, I’m not sure who else in her family learned to fly, but it’s quite clear in Margo’s book that her first time flying was that moment with Frankie and Yankee Boy. These days, Margo’s stories are a bit iffy on the facts, but they still have a lot of that old flare. In an odd way, the language of dementia seems to transcend the earthly bonds of the dictionary. The word “flying,” for instance. In the well-oiled mind, it means airplanes; in Margo’s story, it takes on the poetic connotation of a woman whose metaphysical feet rarely touched the earth.

One of the difficult dynamics for me to overcome as my mother aged was the compulsion to correct her when she called someone the wrong name, or forgot what year we were living in, or went off on a story that took a plot point from a book she read in 1958 and morphed it into an actual event that happened to her just this morning. Partly, I just like things that are correct, damn it, but moreover, I wanted her to stay with me in the here and now. I couldn’t bear to lose my touchstone, my sounding board, my trusted advisor in all things from love and work to which dish soap is least chafing to the hands.

From my perspective, the Q&A portion of the program was nowhere close to over. I still had much to learn from my mother, and the bitter lesson in my father’s decline was that I am not as talented a listener as I would like to be. I was convinced that conversations were made of words. If words lost their meaning and became malleable, communication was impossible. I didn’t know then that words are the trees obscuring the proverbial forest that shifts with the wind, creating a language of its own.

The willingness to let go of all that was a mountain for me to climb, and it’s a fundamental job requirement for anyone who comes into our home as a caregiver. This is one of the reasons I love Antonio; English is a distant second language for him, but he speaks fluent Margo. And I must admit, it doesn’t pain me to have this gorgeous young man hanging out with us for the evening.

“My husband keeps himself very fit. He’s a handsome man.” Margo pats Antonio’s well-muscled arm. “You seem to be in excellent health. You’re quite attractive yourself!”

I heartily agree as I take our cups to the sink.

“Good night, Mommie.” I lean in behind her, circle my arms around her shoulders.

“Good night, my darling angel,” Margo says.

Then she slips off to her bedroom on the arm of the gorgeous Brazilian, and I head up the stairs with a good book, thinking, What’s wrong with this picture?