In 1932 a new “forces sweetheart” emerged, when Jane—created by Norman Pett—appeared in Jane’s Journal, the Diary of a Bright Young Thing as a weekly single frame in the London Daily Mirror.

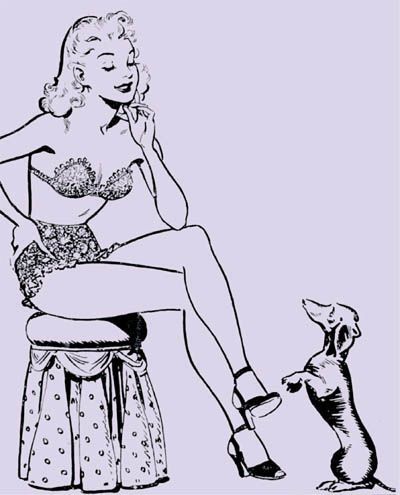

There’s an old truism that you should always write (or draw) about what you know, and Pett took this literally when he based Jane’s look on his wife Mary, who would model for him. Moreover, Jane’s constant companion—her dachshund Fritz—was based on Pett’s own dachshund of the same name.

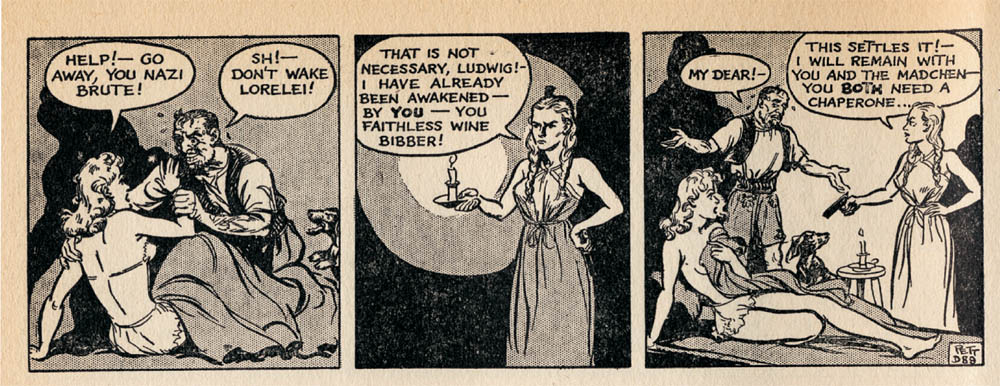

Starting out as a comedy about a society dilettante, the stories soon developed and Jane was often dropped into what would be called—in today’s cinematic censor-speak—“scenes of mild peril.” The danger she faced was often more of a farcical scrape than true menace, and it usually involved her losing items of attire.

In 1938, Don Freeman started writing scripts, helping to build the background story and continuity. That same year Mary Pett grew tired of posing for her husband and Norman discovered his second muse—the model and actress Christabel Leighton-Porter—at a life drawing class.

As war broke out across Europe in 1939, Jane began shedding more and more clothes, keeping up the morale—and everything else—of the British men fighting abroad. Until 1943, Jane rarely stripped to more than her underwear, but when an episode finally revealed her completely nude, the American newspaper, Round-up, apocryphally noted that the 36th Division of the British Army stormed forward six miles in one day in Burma. Consequently, the newspaper strip was deemed so important to the war effort that submarine captains were given copies of the Jane strips weeks in advance, so their crews didn’t miss out on any crucial developments.

Christabel Leighton-Porter toured the music halls with a striptease act as Jane, and she soon became as popular as the character herself. But the chaste side of Jane—her innocence—remained a key factor in her popularity. The strip was never smutty or vulgar, but somehow pure, harking back to the seaside postcard humor of the Edwardian era. In fact, sex was the last thing on Leighton-Porter’s mind. “I didn’t even think about it,” she recalled. “Wherever I have been, people have asked why it was so popular. It’s something I have never been able to answer. It was done in such a way that made Jane a real person. It was more about what you didn’t see than what you did. I was always treated with the greatest respect.” And when Leigh-Porter met the head of the royal household, the Lord Chamberlain asked her, “Tell me my dear, what do you do in your act?” “Well,” explained the real-life Jane, “at one stage I turn my back to the audience, take off my bra, and then cover my breasts with my hands as I turn around.” There was a momentary pause before the King’s aide replied, “You must have very large hands.”

In support of the war effort, Leighton-Porter stripped for her first nude photo session for the Daily Mirror just after D-Day, following in the footsteps of her cartoon sibling. After the war, the model went on to headline in the 1949 movie, The Adventures of Jane.

Jane, in a typical semi-clad pose with her pet daschund Fritz, drawn by creator Norman Pett.

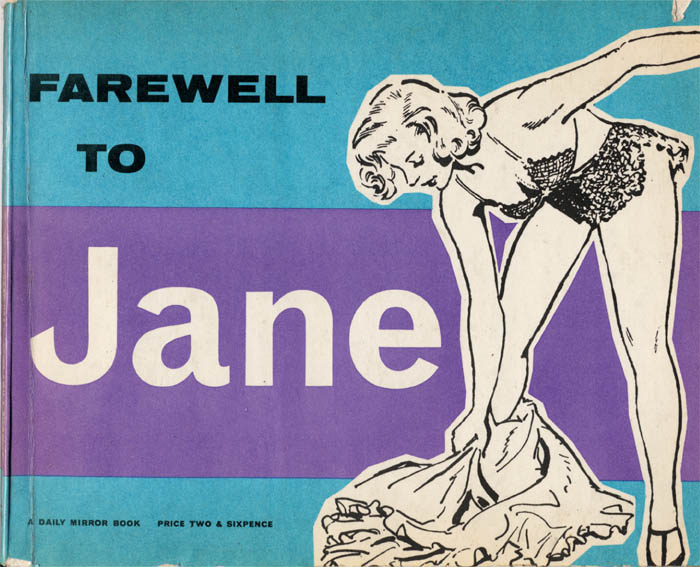

The Daily Mirror collected some of Jane’s earlier adventures into one volume in 1960, a few months after her last newspaper appearance.

Spurred on by the success of Jane, many other British tabloid newspapers tried to capture some of the glory. The Daily Express tried Paula by Eric R. Parker in 1948, while the Evening News published Judy by Julian Phipps on January 1, 1949. But none achieved the notoriety of their older sister.

In 1948 Pett was “retired” from the Jane strip and his assistant, Michael Hubbard, took over. Pett went off to create a rival stripping character—Susie—for the Sunday Dispatch, while Hubbard tried to update Jane with a Rip Kirby-style realism. But his changes fell on blind eyes and Jane eventually sailed off into the sunset after marrying her beau, Georgie Porgie, on October 10, 1959. Norman Pett died the following year.

The Mirror tried to revive the Jane strip several times, culminating in Jane—Daughter of Jane, drawn by Dutch artist Alfred “Maz” Mazure in 1963. Yet each time she reappeared she failed to capture the public’s imagination in quite the same way as her “mother.”

It was a further 23 years until Jane made another comeback, this time as a British television series starring Glynis Barber in the title role. The BBC’s 1982–1984 show used Pett’s drawings as backgrounds for the real-life actors to maintain the comic strip’s feel, and left the original risqué humor intact. Three years later, Jane had her final outing in the 1987 film Jane and the Lost City, directed by Terry Marcel.

Jane’s return after World War II, illustrated by Norman Pett.

Jane’s first completely nude appearance in a newspaper strip in 1943.

Jane fends off a lacivious Nazi captor in this WWII strip by Norman Pett.