At the dawn of the 20th century, American men’s magazines were on the brink of their golden age. From 1900 to the late 1950s, the magazine was to be the premier source of entertainment and information for men, with unbelievably high circulation figures that reached into millions of copies. And with the curvaceous cuties came the comics.

One U.S. soldier returning from post-WWI Europe, Captain Wilford H Fawcett, began publishing his own magazine, Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang, in October 1919. Most likely inspired by the saucy Tijuana Bibles he’d seen handed around, Fawcett printed 5,000 copies of his first issue. After giving copies to wounded war veterans and all his friends, he shipped the surplus to hotel newsstands.

Any intention of publishing a magazine solely for veterans was quickly abandoned when the magazine’s circulation went stratospheric, allegedly “soaring to the million mark.” But as Wilford’s son, Roscoe K Fawcett, recalled, the figure may have been slightly exaggerated: “My father made a fortune on Whiz Bang. It cost only 4 cents to produce each issue… the cover price was 25 cents and the circulation was [only] around 500,000.”

Despite its popularity, Whiz Bang (the title was the nickname for a World War I artillery shell) was always considered somewhat disreputable, as was Fawcett’s down-at-heel Smokehouse Monthly, launched in 1926. As may be expected in a male humor magazine, many of the jokes concerned women, but there was a thinly veiled misogyny present throughout. This uncomfortable undercurrent continued throughout many other men’s magazines from the 1920s right up to the 1960s.

The content of Whiz Bang included off-color cartoons, limericks by convicts (usually on death row), fallen women, and gamblers. Captain Billy also printed hundreds of jokes about scanty costumes: “We call her bridge table because she has bare legs and no drawers.” Whiz Bang was never subtle nor sensitive. Racism was rife in the 1920s, as demonstrated by Captain Billy’s description of Rudolph Valentino as “the romantic wop.”

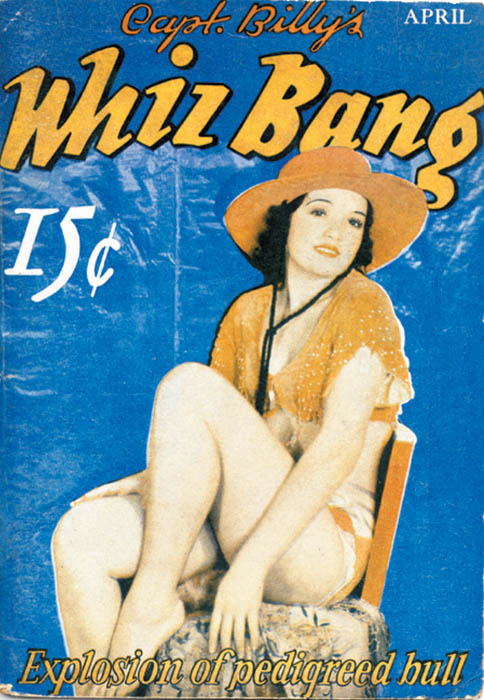

During the Depression, Fawcett reduced his cover price to 15 cents, added even raunchier jokes, and briefly experimented with mammary nudity—which kept the magazine going into the late ’30s. The profits from Whiz Bang funded many other Fawcett Publication magazines and comics. These would play a crucial role in the development of men’s magazines, combining cartoons with sexual imagery and bawdy “jokes”—creating the “gags and girls” formula that would become the staple diet for men’s magazines for the next 50 years.

Animator and Playboy cartoonist Dean Yeagle’s creation, Mandy, discovers some unexpected guests in her bikini.

Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang from November 1923. An “explosion of pedigreed bunk” that initially used illustrations of saucy ladies on the cover.

By the 1930s, Whiz Bang was struggling against competition from rivals such as Esquire, so Fawcett dropped illustrations in favor of photographic covers.

Whiz Bang’s “half brother” publication, Smokehouse Magazine, was launched in 1926. This cover’s line art was poor compared to Whiz Bang’s sumptuous full-color paintings.