Irving Klaw was born in Brooklyn on November 9, 1910. Of his two brothers and three sisters, Irving was closest to his younger sister, Paula. Irving’s first business venture was as the owner of a book and photo shop at 209 East 14th Street in Lower Manhattan. By 1939, the photos were outselling the books, so Irving expanded the business and opened Irving Klaw Pin-Up Photos, which flourished after World War II. Paula had joined her brother’s enterprise at the start, and they sold publicity photos from Hollywood through their newly named Movie Star News mail order catalogue. Public demand for more fetishistic material soon drove them to set up their own studio above the shop. Customers would often ask Klaw for “specialist” girlie pictures, which they were unable to come by in the magazines on the newsstands, and he would create photosets for them.

An up-and-coming model—Bettie Page—met Klaw in 1952, just as she was starting to make her debut in Robert Harrison’s “gags ’n’ girls” magazines, such as Eyeful and Whisper. Page would eventually become a comic book icon herself, over 30 years later, thanks to the efforts of artists like Olivia De Berardinis and comic creators like Dave Stevens.

Klaw photographed Page in various states of bondage and most of the photos were sold on a lucrative subscription basis, with customers often making specific requests regarding the scenes and layouts. Many of the bondage scenes were inspired and financed by “Little John,” a customer and attorney who remains anonymous to this day.

Klaw’s photographs and films have a bizarre, fresh innocence about them, thanks to Page’s down-to-earth approach to the work: “I was not trying to be shocking, or to be a pioneer. I wasn’t trying to change society, or to be ahead of my time. I didn’t think of myself as liberated, and I don’t believe that I did anything important. I was just myself. I didn’t know any other way to be, or any other way to live.”

While Klaw’s relationship with Bettie Page—and their subsequent films and photos—are what the publisher is most famous for, he also published and distributed stacks of illustrated adventure/bondage serials by fetish artists Eric Stanton, Gene Bilbrew, John Willie, and others. These booklets had higher production qualities than the Tijuana Bibles, and were distributed by a more sophisticated mail order service.

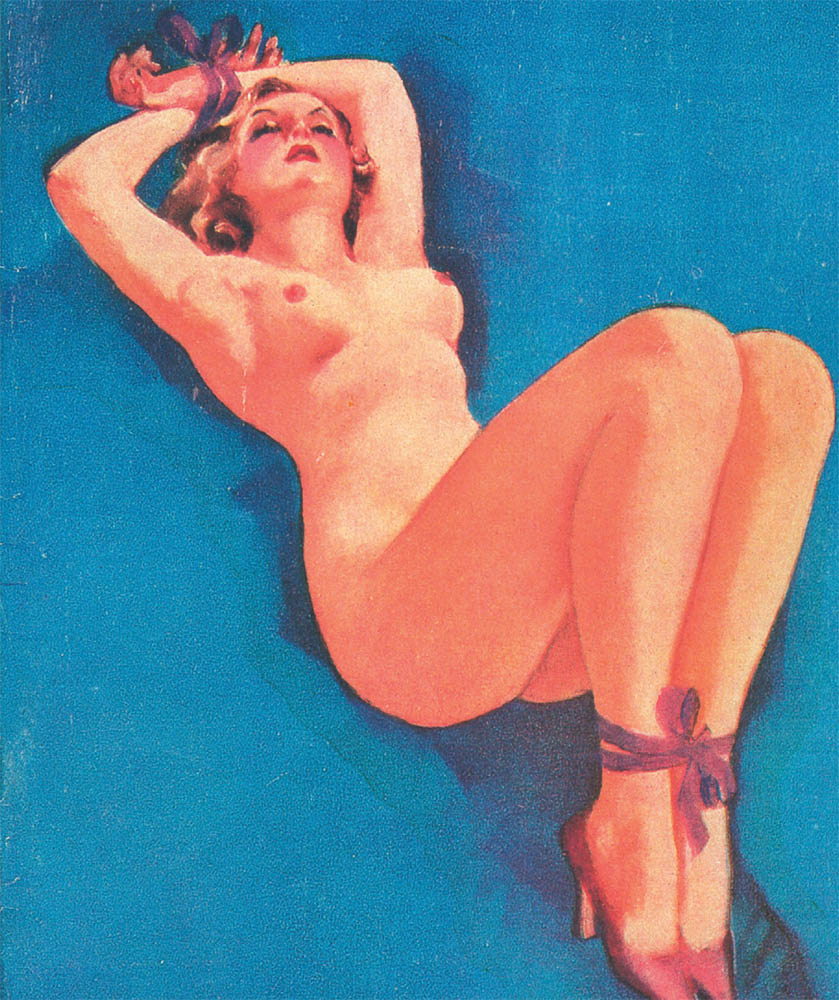

This beautifully painted cover from French Frolics magazine shows that there was an interest in bondage artwork as early as 1933.

A close-up panel of John Willie’s Sweet Gwendoline comic strip reveals the artist was equally adept in pen and ink as he was in watercolor.

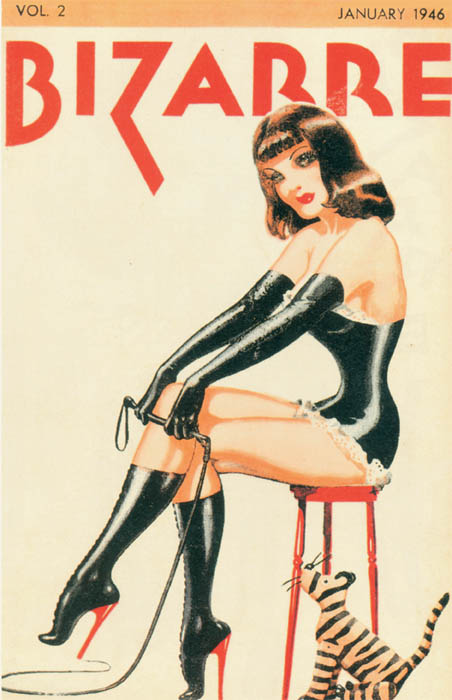

John Willie’s unique fetish-wear designs filled the pages of Bizarre magazine in the 1940s.

The cover to the second issue of Willie’s self-published Bizarre magazine.

By 1955, Irving Klaw was allegedly grossing $1.5 million a year, supposedly through mail order sales of his fetish movies, photographs, and comics. But that year also saw Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee (ironically, Bettie Page’s home state) came to New York with a Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, and he was out for blood. With the moral majority of 1950s America running rampant with “Red Scare” communist paranoia and public burnings of “evil” comic books such as E.C. Comics’ horror and crime titles, Kefauver set his sights on Irving Klaw’s sexploitation empire. The Kefauver Committee investigated ludicrous claims that Klaw’s material was directly linked with juvenile delinquency. The Post Office, joined the witchhunt and, on the advice of his lawyer, Klaw destroyed thousands of bondage pictures— in a bid for clemency from the judge. Fortunately, Paula Klaw secretly saved as many images as she could. Bettie Page never actually testified on Klaw’s behalf, and she was so disturbed by the government’s hounding that she quit modeling two years later.

Klaw shut up shop, but continued to supply mail order customers with material. Tragically, he found himself indicted on June 27, 1963 for “conspiracy to distribute obscene material” through the US Postal Service. Klaw was found guilty, and sentenced to two years in jail and a $5,000 fine. The verdict was overturned by the Federal Court of Appeals, and Klaw was released on a $10,000 “bail”, but by then he had wearied of the relentless legal opposition. The stress and strain contributed to his untimely demise in 1966, due to complications from untreated appendicitis.

Klaw always went to great pains to make sure his photographs contained no nudity as he knew this would make the material pornographic, and therefore illegal to sell via the mail. Models were even required to wear two pairs of panties so that no pubic hair could be seen. His comics were also undefined by existing pornography laws as they had failed to keep up with society’s fast changing peccadilloes.

“My grandfather never really understood what he had done wrong. He had never knowingly broken any laws and always paid his taxes. He was just a businessman,” wrote Rick Klaw. “For the remainder of his life, Irving Klaw would collect bondage images from wherever he could find them, hoping to redeem his reputation by demonstrating that others were producing similar images without legal problems.”

This page from Willie’s Bizarre magazine had this caption: “If you are handicapped, you can still make the best of what you’ve got.”

A “Pony Girl” by John Willie. The artist was drawing these fetish images as early as the 1940s, having been inspired by London Life magazine.

A rare, but beautifully executed watercolor by John Willie, one of Klaw’s contemporaries.