Guido Crepax is probably best regarded as the capo di tutti capos of Italian—if not European—erotic comics, a healthy lineage that exists today in the form of greats like Milo Manara. Crepax was born in Milan on July 15, 1933 and studied architecture at the city’s University, though without any real intention of becoming an architect. “As soon as I started the course, I wanted to quit,” he said, and he worked as a graphic artist and illustrator while studying.

After graduating in 1958, he realized his true calling was in the world of sequential storytelling, and he made his comics debut in 1965 when he joined a new comics anthology magazine, Linus. He created the fantasy/ superhero comic strip Neutron, which featured a reporter called Valentina. This seemingly innocuous figure would become Crepax’s fictional muse and also his magnum opus. He drew her adventures over the next 31 years, eventually retiring her in 1996. Unusually for comics, Crepax aged her appearance over the years, as he was frustrated by the lack of realism in a medium where everyone was perennially young.

With her trademark short, black, bobbed hair, Valentina was visually based on the silent film star Louise Brooks, whom the artist admired greatly. Valentina’s adventures filled an impressive 25 volumes, including Lanterna Magica (Magic Lantern) in 1977 and Valentina Pirata (Valentina, Pirate) in 1980, the first in full color. Her adventures were a mixture of surreal spy adventures, fantasy, and science fiction. In later adventures her stories became more sexploitational as—like Jane and many other female heroines—she found herself in more and more compromising situations.

With her black, bobbed hair, Crepax’s depiction of “O” from The Story of O is very similar to his most famous creation, Valentina.

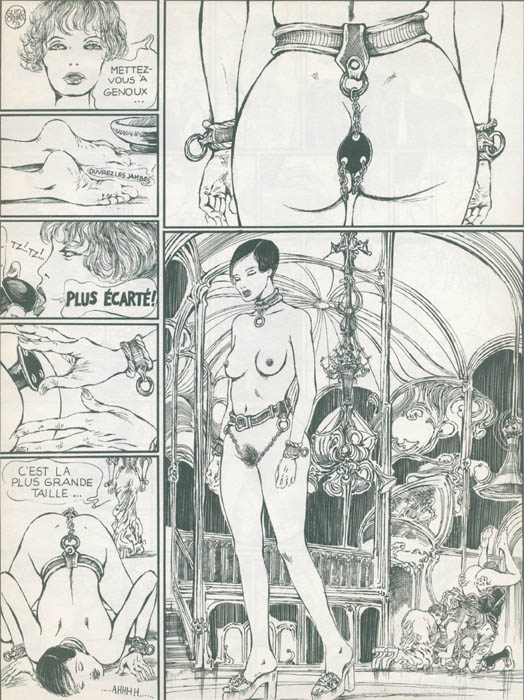

Crepax’s frameless montage from Justine contrasts the sensual beauty of the woman with the ape-like crudeness of the man.

But it was Crepax’s recurring themes of victimized girls, sadomasochism, submission, and domination that were his most controversial. After Valentina, he created other female heroines, such as Bianca in the series La Casa Matta (1969), Anita in Anita, Una Storia Possibile (1972), and Belinda in 1983. In 1978, Crepax adapted Marayat Rollet-Andriane’s infamous erotic novel, Emmanuelle, about a young woman’s sexual explorations.

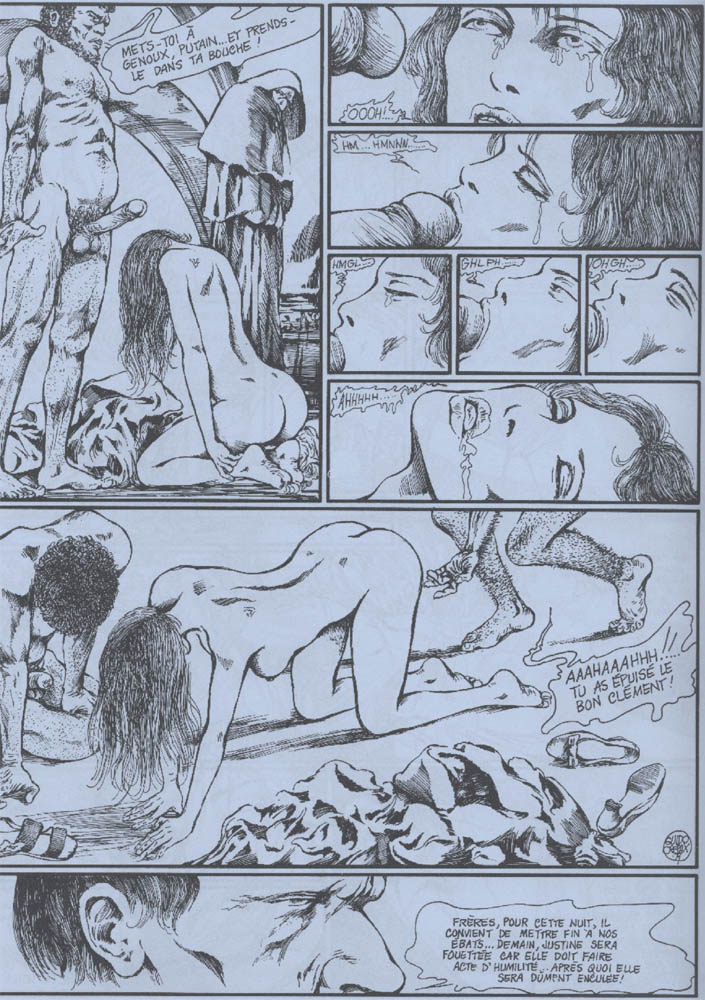

He also adapted numerous classic S&M stories, including the Marquis De Sade’s Justine (1979), Pauline Réage’s The Story of O (1975), and Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s Venus in Furs (1984). In them, willing female and male slaves are seemingly both brutalized and transformed by the experience.

Crepax drew slender, delicate, almost fragile girls, who had a will of iron. While most of his art was created using pen nibs dipped in ink, his fluid strokes gave the appearance of brush marks. It was his trademark elongated women and unusual page layouts that marked Crepax out from other artists. His comics feel more cinematic than most, often including pages without dialogue that simply feature a series of closeups of body parts, and more importantly facial expressions, all engaged in erotic bliss.

Crepax died on July 31, 2003 at the age of 70, shortly after completing his adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. He left behind a body of work that continues to influence artists from across the world—particularly America, Spain, and his native Italy.

A page from Crepax’s adaptation of DeSade’s Justine, which portrays the tragic life story of a young woman in pre-revolutionary France.

The Story of O recounts the tale of a Parisian fashion photographer who gives herself to an élite group of men in the ultimate act of female submission—a popular fantasy and an area in which Crepax’s art excels.