Erotica has a long, illustrious history, dating back to mankind’s earliest artistic endeavours, from simple fertility statues to scenes portraying every type of congress imaginable. From 5th century Greek urns and ancient Roman mosaics, to the Japanese shunga prints and Indian Kama Sutra of the 18th and 19th centuries, erotic and arousing art has held a very important position within the history of creativity.

So it is no surprise that as the human race has developed more sophisticated ways of expressing ideas, erotic art would be at the forefront. As simple illustrations started to develop into cartoon art, using speech balloons and sequential imagery to portray an ongoing narrative, the birth of comic strips would invariably be entwined with the birth of erotic comics.

But erotica has always been the preserve of the upper classes, and not meant for the plebeian masses, for fear it might “deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences,” as the Victorians put it. Obviously the upper classes were above such base desires and could appreciate the work purely for its artistic merit. This laughable attitude prevailed for decades, and coupled with the fact that comics and cartoons—erotic or not—had always been given short shrift by the intelligentsia, it meant that erotic comics were doubly dammed.

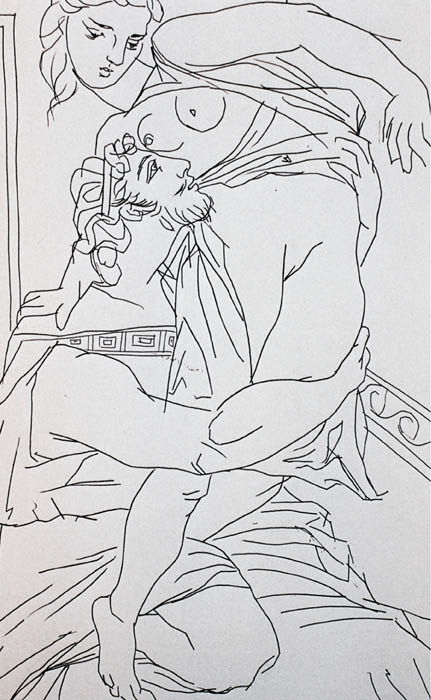

Viewed very much as “low art” for the masses, it is only within the last 20 years that a certain amount of respectability has been afforded to this mass-produced art form. Yet history reveals that fine artists have long been influenced by their less feted brethren. Pablo Picasso, for example, was a huge comic fan, and an avid reader of the New York Journal’s comic strip Katzenjammer Kids. The strip was created by German immigrant Rudolph Dirks in 1897, and inspired Picasso towards modernism. His own work wears its cartoon inspiration on its canvas, particularly in his more erotic work, such as his cartoon sketches Couple (1964) and the lesbian Femmes Nues a la Fleur (1971).

Pablo Picasso’s 1934 illustration of the Greek sex comedy, Lysistrata, possibly inspired by the great Aubrey Beardsley drawings created 40 years earlier.

One of Picasso’s earliest proto-comic experiments, The Dream and Lie of Franco, depicts an abstract General Franco waving his enormous phallus over Spain (in the 2nd panel).

In January 1937 Picasso etched the first six scenes of The Dream and Lie of Franco. In this satirical proto-comic strip, a bulbous version of Don Quixote travels on horseback, raping Spain with his huge phallus. The strip was an angry attack on Franco and the Spanish civil war, and acted as the template for his infamous painting Guernica.

In the 1960s, Pop artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein co-opted their childhood comic book influences and transferred them on to canvas, instantly “legitimizing” them in the eyes of the artistic elite and dragging comic art out the gutter. Lichtenstein’s reworking of the romance comics of the 50s told of unrequited love, and seething—but repressed—passions, and would adorn postcards and posters for decades to come. Yet the originals, by great artists such as Mike Sekowsky and John Romita Sr., remained dismissed for another 30 years.

Erotic comics have always had to battle with the tricky debate of erotica versus pornography. In a medium that has been long-regarded by the less enlightened as purely entertainment for children or the “educationally sub-normal” it appears an instant anathema to combine sexual imagery with comic books. Indeed, US-based Psychologist Dr. Fredric Wertham’s 50s witch-hunt against horror and crime comics completely missed the fact that the majority of the titles were intended for an adult readership. Not only that, but his own prejudices began to cloud his judgement as he started seeing sexual imagery everywhere, from the supposed gay relationship of Batman and Robin to the absurd view that “when Wonder Woman adopts a girl there are lesbian overtones.” Sadly, Dr. Wertham obviously forgot Sigmund Freud’s important caveat—“sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.”

However, there is no doubt that there is art contained within this book that some might regard as “pornographic,” that is to say, an “explicit representation of the human body or sexual activity with the goal of sexual arousal.” However, I would argue that everything included in here is in fact erotica—as defined as “portrayals of sexually arousing material that hold, or aspire to, artistic or historical merit.” The very fact that every piece of work here has taken someone with some artistic ability to create it, instantly elevates it above the average “skin flick” or hardcore photographic magazine. And I would vehemently refute that any of the work contained would ever “corrupt or deprave” anyone looking at it, as defined by the archaic British Obscene Publications Act. In fact, the deferring terms are quite meaningless and are an entirely Victorian construct, created to “protect” the prudish (and highly hypocritical) morals of the time. Today they are obsolete and we can regard these images without the prejudices that have plagued comic art for over a century. As the late artist Stephen Gilbert quipped; “The difference between erotica and pornography is simple. Erotica is what I like. Pornography is what you like, you pervert!” Or, more succinctly, as the Viennese architect Adolf Loos declared in his 1908 manifesto: “All art is erotic.”

“Ha! My smart-ass wife bet me you wouldn’t put out!” This Bill Wenzel cartoon appeared in Sex To Sexty #41 in 1972.

Bill Ward’s exquisite pencil drawn pin-up was the pinnacle of '50s sex sirens.