Introduction: A Therapy Session About Tech

In this country, you need a license to do anything that might get you into trouble: drive a car; own a gun; get married.

But when it comes to technology, they shove you out of the nest without so much as a pat on the back. There’s no driver’s ed class for tech. There’s no government pamphlet that covers the essentials. Somehow, you’re just supposed to know how to use your camera, phone, e-book reader, GPS, printer, Web browser, e-mail system, and social network.

And that’s only half of the problem.

■ Why tech moves so fast

Every industry has a business model, right? A system of making money.

Sometimes the transaction is obvious: You hand over a bill, and you take home a jar of pickles.

Sometimes it’s sneakier: You pay only $50 for an inkjet printer, but you pay many times more for the ink cartridges. (If you do the math, you’ll find that printer ink comes out to about $8,000 a gallon. And you thought gas companies were greedy?)

Well, the technology industry has a little business model of its own, and it’s based on insecurity.

Yours, to be precise.

Every year, it introduces a new version of whatever it is you’ve bought. That software, that phone, that tablet. Of course, nobody forces you to upgrade to the new one, but you’re made to feel feeble and obsolete if you don’t. “What iPhone model do you have?” “You’re not still running that version of Word, are you?” “What generation iPad is that?”

This annual tech upgrade cycle has become so ingrained that the cell phone carriers invoke it with a slogan: “New every two.” Every two years, you’re supposed to want a new phone, a new camera, a new laptop. Otherwise, you’re a loser, right?

■ How featuritis happens

This annual insecurity cycle works out beautifully for tech companies. But there are two problems with it.

First, if we believe in “new every two,” we have to throw away the gadgets we bought last time. They have to go somewhere. The landfills fill up with the stuff, and those discarded gadgets leak some pretty toxic juice.

Second, how do you suppose the hardware and software companies entice you to buy their new versions each year? Two words: more features.

Each year, they pile on more and more and more features. More controls, more buttons, more bloated software.

Trouble is, if you slather on enough new features, you eventually wind up adding stuff nobody has actually asked for. Eventually, you make your product a monstrosity.

Consider Microsoft Word: At one time, it was a word processor. Today, it’s also a Web-design program, a database, and a floor wax. The average person uses about 6 percent of Microsoft Word’s features (and probably feels inadequate as a result).

These companies don’t seem to realize that people have lives. Most people have work to do, places to go, people to see, families. We’re not full-time technologists.

You can see where all of this is going. Eventually, you find yourself the proud owner of technology products that overwhelm you. Maybe you know enough to get by—maybe you don’t even know that—but you have the nagging suspicion that you’re not getting the most out of your tech.

Who’s there to teach you the features that matter and give you permission to ignore the rest?

■ How this book happened

I first noticed the growing “I don’t even know the basics” crisis years ago. I was waiting in a book publisher’s office, watching a receptionist become increasingly frustrated. She was editing something on the screen. She was trying to select just one word in a document.

And she was doing that by painstakingly dragging her cursor across the word. Each time, she’d go a little bit too high or too low, and she’d wind up selecting an entire extra line of text.

After ten minutes of this, I couldn’t stand it: “Why don’t you just double-click the word?”

She didn’t have a clue you could do that! (See here if you don’t, either.)

In any case, I thought I should maybe write up a list of my favorite “things you thought everybody knows, but they don’t” tips on my New York Times blog. BOOM: 1,500 reader comments in two days.

Then I put together my favorite ten of them and demonstrated them live onstage at the 2013 TED conference (a trendy annual gathering dedicated to Technology, Entertainment, and Design). The TED people posted the video of that talk on ted.com. BOOM: 4 million views.

I was convinced that I was onto something. There really isn’t anyone putting together a master list of the knowledge that’s essential for today’s technology.

Or, rather, wasn’t. Congratulations: You’ve found it.

This book’s mission in life is to collect, in one place, every essential technique you’d think everybody knows about technology—(but you’d be wrong.)

You may know some of these tips already. No problem; skim them and savor the rosy glow of smug superiority.

Other tips might seem more like geeky shortcuts. That’s fine, too. Adopt the ones that seem worth it for you.

What binds all of these tips together, though, is this: They make using technology faster and easier. Fewer steps. Less hassle. Less annoying.

The point is that if this book teaches you only one new trick that makes your life easier…

Well, then it wasn’t a very good book.

But you’ll probably pick up a lot more than that!

■ When to buy new tech

You’ll never stop the Great Treadmill of Technology Upgrades. It’s just the way of the world: Whatever technology you buy today will be obsolete soon.

But at least you can arm yourself to cope with it.

You can learn, for example, when new gadgets will be introduced each year, so you’ll never be caught by surprise. You don’t want to be that sucker who buys the iPhone 6 three weeks before the iPhone 7 comes out.

In general, Apple introduces a new iPhone every September and a new iPad every October. The iPods are updated every September, too.

Samsung’s Galaxy S phones appear every April.

New camera models come out in February and October.

New everything else comes out just in time for the holidays.

You can play the game in one of two ways. If you wait to buy until the end of the product’s life, you’ll generally save money, because the price will have slunk downward since its introduction. (The exception: Apple products. Their prices don’t sink much over time.)

And if you wait to buy until the new product comes out, then you’ll avoid the sinking feeling that you’re a sucker.

■ Save big money on new tech

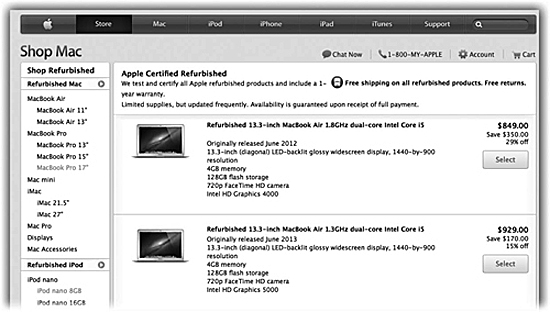

Because we live our lives on cell phones and tablets these days, we are—finally—easing off on buying new computers. But when the time does come, here’s a tip: Buy a refurbished computer. They’re listed in special areas of the Web sites for Apple, Dell, HP, and so on. (To find these special pages, use Google to search, for example, for “refurbished Macs” or “refurbished Dell.”)

“Refurbished” isn’t what it sounds like; these are brand-new computers. There’s nothing wrong with them. Usually, they were bought and then returned for some reason, sometimes without even being opened. They’ve been inspected even more thoroughly than new machines; they have the same warranty—but they cost less.

You should also be aware that somewhere out there, at this moment, there’s probably a discount coupon code for anything you’re about to buy. Camera, blender, car wash, restaurant, flight. Before you buy anything online, search for it at RetailMeNot.com to make sure you’re not throwing money away (see here).

■ How to get rid of your old gadgets

Sooner or later, you’ll get new electronics. Obsolescence, or your fear of being left behind, will drive you to upgrade.

Do the world a favor: Don’t throw the old one in the trash.

If you think it might still have some value to someone, you can sell it to Gazelle.com, a huge online gadget recycler. Even a three-year-old used phone might get you, say, $35. And the process couldn’t be easier. Gazelle sends you a box with the return postage already on it. Put in the phone, send it away, and cash the check. (It accepts even broken phones.)

If your gadget is so old or so broken that nobody would possibly want it, than drop it off at a Best Buy or Radio Shack store. Those companies offer free recycling. Just drop off your stuff and sleep well, knowing that any valuable parts of your junk will be reclaimed and reused—and that the rest will be safely disposed of.

■ The very, very basics of technology

To use any technology, you have to know a little bit of terminology. This book assumes that you’re familiar with a few terms and concepts.

Android: Android is software written by Google for touch-screen cell phones. It’s very flexible and attractive, so it’s very popular. It was designed to look and work a lot like the iPhone, but it’s free to any cell phone company (Samsung, HTC, Sony, and so on) that wants to build it into its phones.

You know how the battle of computers has always been between Mac and Windows? For cell phones, it’s between Android and iPhone.

You can also get tablets, computers, and even watches that run variations on Android.

app: It’s short for application. When you describe your computer, you might say, “I use two programs every day: Quicken and Microsoft Word.” On a phone or tablet, you’d call those apps.

browser: A Web browser is the program you use that enables you to read Web pages. A browser comes built into every computer, phone, and tablet—its name is probably Safari or Internet Explorer—but there are many alternative browsers, most of them free. Firefox and Chrome, for example, have amassed armies of rabid fans.

clicking: To click is to point the arrow cursor at something on the computer screen and then—without moving the cursor—press and release the clicker on the mouse or trackpad. To double-click, therefore, means to click twice in rapid succession, again without moving the cursor.

When you’re told to Shift-click something, you click while pressing the Shift key. Alt-clicking and Control-clicking work the same way—just click while pressing the corresponding keys.

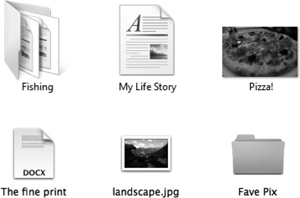

drag: To drag means to move the cursor while holding down the button. The purpose is usually to move something that appears on the screen, like an icon.

icons: These colorful inch-tall pictures represent each app, program, disk, and document on your computer, phone, or tablet. If you click an icon once, it darkens, indicating that you’ve just highlighted or selected it. Now you’re ready to manipulate it by using, for example, a menu command.

iOS: It stands, basically, for “iPhone/iPad operating system.” It’s the software that runs on an iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch.

Apple had to invent that term—iOS—because people got tired of saying, “the software that runs on an iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch” over and over.

keyboard shortcuts: When you’re at your computer, hands on the keyboard and on a roll, grabbing the mouse breaks your momentum and wastes time. That, at least, is the passionate belief of people who prefer keyboard shortcuts: key combinations that trigger software functions without your having to move your hands to the mouse or trackpad.

For example, in word processors, you can press Control+B to boldface a selected word (that’s ![]() -B on the Mac).

-B on the Mac).

Macs, Windows: The most popular computers in the world are Macs (made only by Apple) and Windows PCs (made by Dell, HP, Lenovo, Toshiba, and many other companies). The computer you own is probably one or the other. (Hint: If it has an Apple logo on it, it’s a Mac.)

Generally, software programs—say, Photoshop or Quicken—work identically on Macs and PCs. But the keyboards on Macs and PCs are slightly different, as are the ways of doing things.

(This book has three chapters dedicated just to computers: one for Mac tips, one for Windows tips, and one for tips that work for both.)

menus: These are the words at the top of your screen: File, Edit, and so on. Click one to make a list of commands appear.

All right—you’ve now completed your orientation. Keep hands and feet inside the tram at all times; you’re ready for Pogue’s Tech Basics.

■ Note About Software Versions

When you’re a technology writer, you labor under a very special curse: Whatever you’re writing about becomes obsolete by the time you’re finished writing the book. Or even the paragraph.

Most of the tips in this book will work no matter what phone, tablet, computer, or software version you have at the moment. If you encounter some steps that don’t seem to match what you’re seeing, it may be that you’re using an older or newer version than what’s described in these pages.

Which, for the record, are these:

• iPhone and iPad: This book covers iOS 7 and iOS 8.

• Android: The version described in this book is 4.4 (“KitKat”), but be warned that each phone manufacturer often makes its own changes to Android.

• Mac: This book describes Mac OS X 10.9 (“Mavericks”) and 10.10 (“Yosemite”). Most of the illustrations show Mavericks, but despite Yosemite’s cosmetic makeover, the features described on these pages work the same way.

• Windows: This book describes Windows 7, 8, and 8.1, with a few references to older versions tossed in for spice.