10

WE AREN’T EVEN AT THE WORST PART

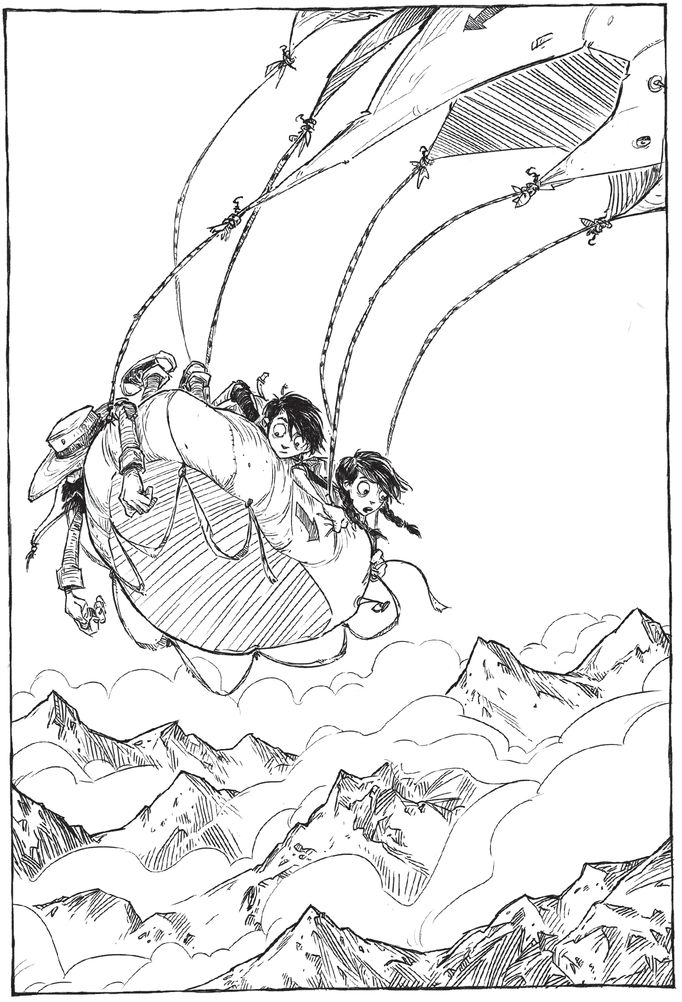

THERE WAS A ROAR, a sickening spinning feeling, and a blinding light. For a moment, it felt as if all the air had been sucked out of the children’s lungs by a cruel vacuum cleaner. The air was thin that high up, but luckily, they were falling fast toward better air. Unluckily, they were falling fast toward the ground too. From thirty-eight thousand feet even falling into water was like landing on cement. And they were falling toward an icy mountain.

Oliver prayed their do-it-yourself parachute would work. If he and his sister died, he would never get to see what happened in the final season of Agent Zero, which was about a teenage superspy living a complicated double life. Who would turn out to be Agent Zero’s real father? Who had planted the bomb in his algebra textbook? Why was Principal Drake talking to the president?

“I need to know the answers if I’m going to have any peace in the afterlife,” he thought.

After a moment of screaming and spinning and thinking about missing Agent Zero, it didn’t feel like they were falling at all. It felt more like they were being pushed up from below, though they were still spinning. They had to hold on tightly to the raft and to their father, and their arms were tiring. Oliver couldn’t handle it anymore. He lifted himself off the parachute, letting it fly out from under him. It snapped and twisted in the air. Two or three of the plastic bags broke away and twirled off into the sky. Oliver feared the whole chute would tear to pieces. The knots connecting it to the raft strained, but held. The canvas ponchos stayed tied and the chute filled with air.

“Well, those were worth more than twenty-three ninety-five,” Oliver said.

Celia’s stomach churned as their fall slowed. They felt themselves jerked upward and then, suddenly, they were drifting. The parachute was working. They weren’t falling anymore, at least not deathly fast. They were floating slowly toward the clouds below them.

“I can’t believe that worked!” Celia shouted.

“Me neither,” yelled Oliver. They both still held tightly to the raft, though they could now let go of their father, who was still out cold.

As they drifted through the sky, the view was amazing. Mountain peaks jutted like teeth through the clouds. Mount Everest rose in the distance, towering above the others. Wind whipped snow off the mountaintops.

When they dropped through the clouds, they saw birds swimming gracefully through the air over rocky plains where herds of yak grazed on grassy patches. Sunlight shimmered off the golden roofs of Buddhist shrines scattered like crumbs over the scenery. A canyon snaked through the mountains, like the earth’s deep veins. Neither of the twins would admit it, but it was a beautiful sight.

“This is just like the second season of Million Dollar Mountain Challenge,ʺ Celia said.

“They had to eat bugs,” Oliver added.

Celia groaned. “We better not have to eat bugs.”

“Like the Thanksgiving before Mom left.” Oliver remembered that night. They had a turkey, like a normal family, but his mother made her favorite recipe from Thailand: roasted centipede and cornbread stuffing with a spicy peanut curry sauce. His stomach, already weary from the airplane food and the fall out of the airplane, felt like it did a backflip. He thought he might yak himself.

That Thanksgiving had been a lot of fun. They had played a geography quiz game, naming all the most extreme points on earth (Mount Everest, in front of them, was the highest mountain, and the Tsangpo Gorge, right below them, was the steepest canyon). After the game, they curled up on the couch and watched a movie. They had to watch it on an old film projector. Their mother loved those old projectors. She loved the sounds they made and the antiqueness of it all. She loved how real they were. She refused to have their home movies transferred to DVD. She even refused to own a DVD player.

She always said that one day the film reels and the old projectors would be civilization’s artifacts for future explorers to discover. They would think it was a kind of ancient magic, how people put little images on film and moved them in front of a light to make them tell stories.

“They are like our shamans,” she would say. “They are our mystic storytellers, conjuring visions and images from light and air. How is a projector anything other than magic?” Their mother made watching a movie seem like an important thing to do.

Oliver couldn’t remember what the movie was that they watched that night, but his mother laughed the whole way through it, while she snuggled with his father, and they popped fried beetles into each other’s mouths (instead of popcorn). Professor Rasmali-Greenberg had come by with some old nautical charts to review, forgetting that it was an American holiday. He ended up watching the movie with the family, and laughing at jokes none of the Navels thought were funny. It was a great night. Too bad his mother had to ruin it all by running off on her adventure just after the New Year. Oliver wiped a tear from his eye.

“Are you okay?” his sister asked.

“Yeah, just that the wind is making my eyes water,” he said.

“Yeah . . . me too,” she said, and Oliver noticed that her eyes were red and teary also. “I wonder where we’ll land,” she added. “They took all of Dad’s maps and books.”

“At least we still have this,” Oliver said, and pulled the scrap of paper with their mother’s note and sketches and the ancient Greek writing from their father’s pocket. It flapped in the wind. “Let’s put it in the backpack. So it doesn’t get lost.”

“I think that air marshal and that stewardess were working for Sir Edmund,” Celia said.

“Really?”

“Yeah, they seemed to know each other and the man next to me who started it all. He was definitely a spy. And they both had matching rings on, rings that made me think of Sir Edmund’s emblem. They were different, but they reminded me of it. They were these jeweled keys.”

“Would Sir Edmund really want us killed?”

“What do you think?”

Oliver remembered what Sir Edmund had said about their father, and he knew that Sir Edmund would do anything to get what he wanted. That’s how he got rich. Their parents always said that discovery was its own reward. Sir Edmund thought reward was its own reward.

“If we don’t find these tablets, then he’ll win the bet with Dad . . .ʺ

“I don’t even want to think about it. If he’s willing to throw us out of an airplane to get what he wants, imagine what he’d do if we were his slaves!”

Oliver shuddered at the thought. Celia looked glum.

While adventures that took them away from the television were bad, forced labor for Sir Edmund every vacation until they turned eighteen would be even worse. The bet their father had made for their freedom was totally unfair. And Celia couldn’t shake the feeling that they’d fallen right into Sir Edmund’s plans. In the library, he had said something about a Council, about his plans for the Navel family. She couldn’t make sense of it at all. It was more complicated than trying to pick up a TV show in the middle of the season.

“So.” Celia decided to change the subject. Secret Councils and ancient documents were her father’s concern, not hers. She was just trying to make sure they got back home alive. “Can we steer this thing?”

Oliver reached up and pulled on one of the cords attached to the parachute. The raft swung hard to the left and tilted, nearly dumping all three of them over the edge.

“Not without killing ourselves in the process,” Oliver said.

“Let’s not do that again,” Celia said.

“I agree,” said her brother, looking toward the ground far below. “I hope landing doesn’t kill us anyway.”