32

WE ARE FAMILY

“I AM SORRY I BROUGHT YOU HERE,” their mother told them quickly. “But it was the only way. I am proud you made it this far, but you still have farther to go.”

They could already hear guards coming around the corner toward them. There was no time for hugs or questions or tears. The monastery was usually a quiet place. The sound of two loud gong strikes and two bodies hitting the floor had certainly been noticed. The abbot dragged the unconscious guards into the cell, tossed the gong on top of them and shut the door.

“You go,” the abbot said. “I will delay them. It is the least I can do for bringing such misfortune to your family.”

Their mother nodded at him, then grabbed Oliver and Celia’s hands and rushed with them down the hall. They slipped behind the door to the nuns’ quarters just as they heard loud voices shouting at the abbot. Their mother stopped a moment to listen.

“What was that noise?” one of the guards demanded.

“It must have been a loud television,” the abbot explained.

“There’s no television here!” the guard shouted.

“Oh, some of our monks have a weakness for the soap operas, The Lovers at 10,000 Meters and whatnot. It’s really quite a fine—” The abbot couldn’t finish his bogus explanation. A guard thumped him on the head and locked him in the cell.

“This way,” Dr. Navel told her children.

“What’s going on, Mom?” Oliver asked.

“I can’t explain right now, Ollie,” she said. “I promise I will. But right now, we have to run, before things get really dangerous.”

“They already are really dangerous!” Celia whisper-shouted. “Sir Edmund said you had us thrown out of the airplane!”

“That was for your own safety. If you had landed in the capital, you would have fallen right into Sir Edmund’s hands.”

“But we fell into his hands anyway!” Celia yelled. “And we could have died!” Her shouts echoed through the halls of the monastery.

“Honey, I know you’re mad,” their mother said, looking around nervously. “But believe me, things will get a whole lot worse if we don’t go right now.”

Without waiting for Celia to reply, she half dragged, half pushed them through a maze of hallways and chambers. Monks and nuns poked their heads out of doors and watched the Navels rush past. They all seemed to know Oliver and Celia’s mother; they all wanted to help. As they rushed, Oliver and Celia heard shouting from down the hall. Nuns were arguing with guards.

“We will go where we please,” they heard Sir Edmund shout. “On the authority of the Council, let us pass! Ouch!”

Someone had hit him with a cooking pot.

“Here we are,” their mother said, stopping in front of a high window. The view looked out over a snowy plain, hundreds of feet below. In the distance, they saw the mountain where their father was held.

“This way,” Sir Edmund was shouting. “Those kids can’t have found this place alone. They have help. I know it!”

Worry spread across their mother’s face, but she hid it quickly.

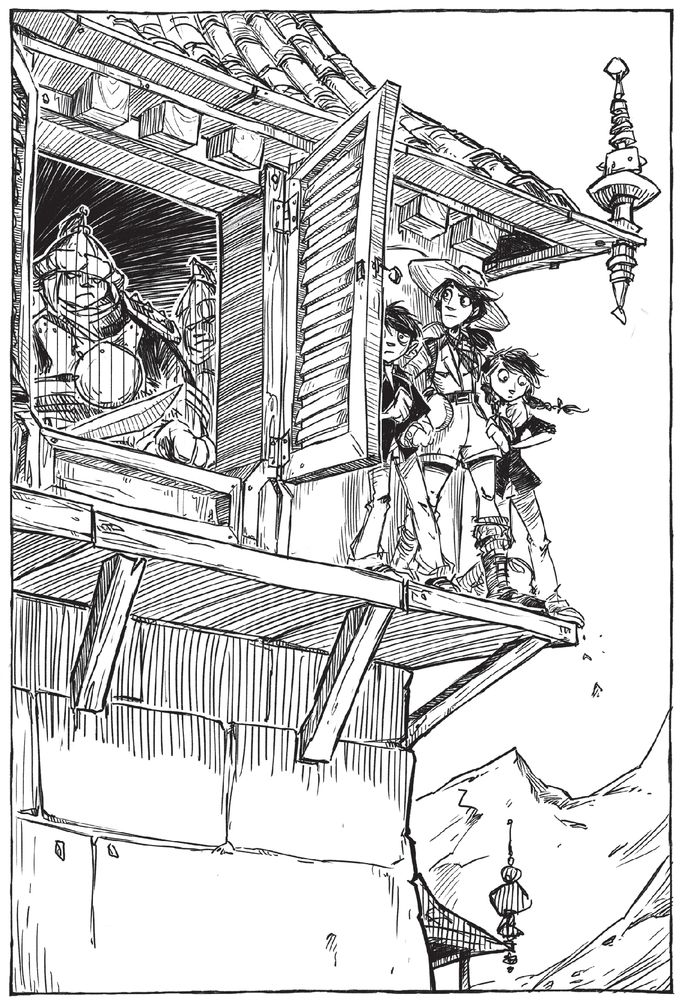

“We have to climb out on the ledge,” she said, stepping up onto the windowsill and pushing open the glass.

“What?” Celia shouted, not even bothering to whisper-shout. “You disappear for three years, have us thrown out of an airplane, and now you want us to step out on a ledge thousands of feet in the air? We are only here because of you! Because of you and that stupid library.”

“She’s just angry,” Oliver said, not wanting to hear his mother yelled at the first time he saw her in years, “because whenever we climb anything, we end up falling. I mean, really falling really far . . . like out of an airplane.”

“I’m sorry, guys. Excitement’s still not your thing, is it? Well”—she looked at Celia—“this time you won’t fall.”

“Why not?” Celia crossed her arms and leaned back on her heels. She was in full-on stubborn mode.

“Because I’ve got you,” their mother said as she reached down and pulled Oliver up onto the ledge next to her. He didn’t resist. If felt good to be with his mom.

“Come on, Celia,” he said. “I’ll go first. Like always.”

They heard the clanking of boots coming toward them. Doors burst open. Nuns screamed and clapped. The sound was getting closer.

“Fine,” Celia said, and let her mother help her up to the ledge. “But you carry the backpack.” Their mother agreed and took it, not even asking what was inside.

They stepped out onto the ledge and knocked the window shut behind them, slipping to the side just as the door burst open.

“No one here,” Sir Edmund shouted, looking into the room. “Next.” He and the guards continued on, while Celia and Oliver pressed their backs hard against the outside wall. The ledge was slippery and every time their weight shifted, they slipped a little bit. The wind pushed at them like a bulldozer and their mother put her hands across their chests, helping them stay back. Down below them on the ground was a large cage with a heavy wooden door that led back into the monastery. In it, exposed to all the wind and the cold, a yeti paced back and forth. It looked right up at Oliver and Celia and roared.

“A yeti!” Oliver yelped, remembering his last encounter all too well. This one was smaller than the one that had attacked him, but still looked ferocious.

“It’s just a baby,” Dr. Navel explained. “They brought it here a few days ago. It hasn’t stopped pacing since they took its mother away.” She grew quiet for a moment. “Okay, stay close to the wall,” she said at last, changing the subject. “Put your feet down carefully in front of you. Don’t shift your weight onto a foot until you’ve set it firmly. You don’t want to slip on the ice. We’re just going around the corner ahead of us. Fifteen feet. That’s all.”

Their mother was going first. Oliver held her belt with one hand and used the other one for balance. Celia held on to him the same way. And they started forward together without another word. It was the longest fifteen feet of their lives. If they survived it, Celia thought, their mother had a lot of questions to answer: three years, a yak and an airplane’s worth of questions.