3

To the Sea! (1927-1929)

The House Without Windows & Eepersip’s Life There was published on January 21, 1927. Interest was such that all 2,500 copies had sold before it reached the shops, and a second printing was ordered.

January 8th, 1927

Dear Peter:

I am deeply grieved that you should suppose I had not written about the book. As a matter of fact, I did write just as soon as I received the package. For, although I did not open the package, I suspected what was in it. Smee can testify that I really wrote, and that to her knowledge (which surely you will not dispute) the letter was posted. Through what convolutions it now is wandering, who knows? Perhaps it isn’t wandering through convolutions but is pursuing a fixed path and, like a comet, will return at a predictable time; predictable, that is, if we knew all the factors—which, of course, we don’t. So that leaves it all very MYSTERIOUS, does it not?

It is well-nigh impossible, I fear, to recapture the first, fine, careless rapture of that letter bearing the familiar signature of JAS. HOOK. I believe I said that I was glad Peter Pan’s Own Story had been told. Practically all that most folk know of Peter, they have had to learn through the medium of (Sir) James M. Barrie; and naturally Barrie may not be perfectly accurate about everything. Then I think I quoted from Phineas Taylor Barnum, a man who would have made a most uproarious pirate if it hadn’t been for a number of things.

The book I discover, now that I have opened the package, to be as charming to the outward view as I had known it would be: binding, title-page, paper, types, and all. I haven’t had the opportunity to dip into it; and I think Helen will explain why, if you ask her. It is (as you will admit) quite necessary that I have a free and untrammelled mind for the two readings of it. I say two; for you will understand that I shall read it once for the sheer story of it, and once for all the mystical allusions between the lines.

Your faithful

Gee-ess-bee

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

730 Fifth Avenue

New York

11 January, 1927

Dear Barbara:

I hope you will get a moment’s pleasure out of learning that the second printing of The House Without Windows is ordered to-day, just ten days before publication. We shall try to make you a new and better jacket to-morrow. The correction “For what? Eepersip had not the slightest idea” will be made; and the sentence in the Colophon about the short descenders will be taken out.

Yours hurriedly,

Daddy.

January 19th, 1927

Dear Peter:

I think your book looks very charming, with its gay sprigged paper and all.

In fine—it’s quite properly Peter-Pannish; and what more is to be said?

Congratulatorily,

Jas. Hook,

Dedicatee

“Il pleut, il pleut, bergère” (“It’s raining, it’s raining, shepherdess”) is a song from Fabre d’Églantine’s 1780 operetta Laure et Pétrarque. The narrative pirate poem is Poppy Island: A Ballad of Pirates, Treasure, Poppies, and Ghosts. I don’t think Barbara got past imagining her “biography” of the gypsy girl.

176 Armory Street

New Haven, Connecticut

January 20, 1927

My dear Mr. St. John:

Thank you for your two delightful letters in succession. You are the person whom I most look forward to hearing from, for you always have something interesting to say. You said in your last: “How strange it must have seemed to you that I have not written before now!” But I myself must now repeat that, and much more emphatically. I am very sorry about it—but how the time does fly!

I liked your last letter very much—for I feel that what you said about The House Without Windows really means something. I see now, perfectly well, my mistake about the vireo—but I was so over-eager in the revision of the story, that I never stopped to think whether the vireo nests in low clumps of grass, or not. Of course, chipmunks do sleep all winter—but, as you say, he was Eepersip’s chipmunk. I’m very glad to hear you liked the book; it means a great deal to have it appreciated by people I care for.

Thank you, too, for the book of songs. I like them very much, and the pictures are delightful. Among the French songs there is one that I learned by heart some time ago: Il pleut, il pleut, bergère.

I was very glad to hear about the little rock garden that you are planning to make. I hope you are going to have columbine in it—the columbine is my favorite flower, I think. And then, would bleeding hearts grow in that kind of place?

Are you well now? It was very disappointing to me, to hear you were sick again.

By the way—Rivernook next spring?

By the way—why don’t we climb Chocorua?

And, speaking of mountains, that reminds me: it is very possible that I shall be going up in the mountains late this month, for a few days, on snowshoes. I am going with two or three friends of mine, and it is very likely that we hover in the vicinity of Lake Sunapee, or climb Mount Kearsarge. And I was so delighted when I first heard about the possibility of it, that I wrote this little poem in anticipation (enclosed).

Here is a bit of news that made me very much excited: my book is in the second printing. The first printing is sold—twenty-five hundred copies—and it isn’t published till tomorrow! Daddy tells me that it is very good selling for a book to go into a second printing before publication—that most books don’t do it.

Speaking of books—if I recover from a bad cough, cold, and hoarseness before next Saturday, I am going to speak over the radio from New York. I shall probably read a narrative poem that I wrote a few days ago. I am both trembling and singing—at any rate, my blood is quite curdled. The trouble will be beginning. Then, I can’t imagine how difficult it will be to talk and talk, and know that people are listening—yet just talking into a motionless, lifeless thing!

The narrative poem is like this (You may think I am very faithless to Eepersip and Nature, but, all the same, I am wild over PIRATES—their unknown islands, masses of blood-drenched gold, mystic maps, wild seas, wild fights, wild deeds!): it contains everything from Blackbeard to myself, from poppies to sea-shells, from butterflies to pieces of eight, from ghosts to living pirates, from maps to palm-trees. And, if you are interested in this (my first attempt at real rhyme and meter) I will send you a copy.

But already I have promised far too many copies that never seem to get far—but they certainly will come in time, for my motto is: Slow but Sure.

But besides this pirate song, I have managed to find time for a story. To be sure, it isn’t written yet, but I have such a firm idea of what I mean to write that it will be very little trouble when I once get buckled down to it. It is about a little girl (nothing like Eepersip, however) who was always having strange, fantastic ideas about things, but most especially about pirates and gypsies. She writes little odd, quaint stories about everything she sees, and wants to be a gypsy herself. When her family moves from a tiny country village to a large city, she begins the business of fortune-telling, with the aid of a friend of hers—and for beautiful, written fortunes she is given various little odds and ends, mostly trinkets; and in this way she collects the necessities for a gypsy costume, until, finally, she is able to wander about dressed just like a gypsy—with golden bangles, and pearl bangles, and bracelets, and anklets, and a full flouncy skirt with bright embroideries. But it is her ideas and her writings that will make the main part of this biography; for I expect to put in many of them just as she might have written them. And in these stories, though she loved things of Nature, and was constantly making butterflies and birds and flowers play the main parts in her stories—she wrote mostly about pirates and gypsies: for her idea of pirates was much the same, mystic, blood-and-gold, unknown-isle as mine; and her idea of gypsies was simply a mysterious tribe who wore the golden bangles she was so fond of, and who told fortunes—just as she did. I am so overflowing with ideas for this new story that—well, if this letter should suddenly break off in the midst of a line or sentence, you would know why; I would be simply overwhelmed with a flood of irresistible ideas.

But all this time Farksolia is languishing. Not because I am tired of it, or because I have no more to say. Quite the contrary: I have had many admirable ideas about it, but simply haven’t had time to write them down. I am looking forward to next summer to get a great pile of writing accomplished: I expect to work a great deal more next summer, rather than running about aimlessly so much. The Natural History of Farksolia has been elongating so that I have decided to make of it a separate volume entirely from the plain, everyday history. There is quite a variety of birds, butterflies, flowers, trees, reptiles, etc. etc. almost indefinitely.

I am enclosing: thanks for the book of songs, thanks for your letters, wishes for your good health, the mountain poem, a promise for the pirate poem (if you want it), a promise for the letter-account, the keys, and lots of love from us all.

Your friend,

Barbara.

Barbara’s mountain poem, dated January 4, 1927.

SONG OF THE MOUNTAINS

I may never touch the snow-fringed Moon,

White-robed, her sandals bound with stars—

Never walk on heaving waves,

Or climb to radiant, fiery Mars.

I cannot dance the burning magic

Of the Earth, with sunbeam rays,

Whirling, softly golden—yet

On snowy sky-peaks I may gaze.

I have not trod those unknown isles

Where raging winds like sea-ghosts blow,

But I know mountains, sky-kissing goddesses,

And I have wandered amid their snow.

For my eyes there is no pirate treasure,

Nor have I seen an albatross,

Color of snow, like the playful foam

That laughing sea-winds gently toss.

But I have touched the feathers of the frost,

Pale mountain-ghosts; and their rippled wings

Are lacy shells from the Sunbeam Isles,

And whisperings from all magic things.

My heart is always with the mountains,

Wind-swept; their peaks deep-fringed with sky—

Up there I still hear the waves,

And the albatross—her lonesome cry.

I wish I had a recording of Barbara’s appearance on the radio. As far as I know no recording of her voice has survived. Symposium was an hour long, and the following listing is from the New York Times.

Today’s Radio Programs

WRNY, New York, January 22, 1927

11:00 A.M. – Symposium. L. Carillo, James Connell, Barbara Follett, Hilda Gold.

Publicity photos for The House Without Windows

Excerpts from A Mirror of the Child Mind, Henry Longan Stuart’s review of The House Without Windows, published in the New York Times on February 6, 1927.

[...] From the moment of her escape on “the foothills of Mount Varcobis” to the last line of the book, Eepersip is the protagonist of her own adventure. No attempt is made to invest the birds and beasts that become her friends with any human attributes, far less human speech. An unbridled imagination is checked at every moment by a literalness of description that is apparently the amazing fruit of keen first-hand observation. [...] Barbara Follett may live and write to 90. But she will never give us the flight of sea birds more truly and vividly than in these dozen and a half words she wrote at the time: “Strong, narrow wings that beat down the air as the birds rose again, to hover and swoop and plunge.” [...] There can be few who have not at one time or another coveted the secret, innocent and wild at the same time, or a child’s heart. And here is little Miss Barbara Follett, holding the long-defended gate wide open and letting us enter and roam at our will over enchanted ground.

Howard Mumford Jones (1892-1980) was a prolific writer. At the time of his review (Barbara Follett: Child of Genius, published in the New York World on February 13, 1927) he was teaching at the University of North Carolina. He would go on to have a long career at Harvard University, served as president of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and in 1964 won a Pulitzer for O Strange New World: American Culture—The Formative Years.

The jacket of “The House Without Windows” says that the book “will be of special interest to teachers and parents who are interested in education; for it is the expression of a child who has never been to school.” This is plain blah. “The House Without Windows” will interest anybody who cares a snap of his fingers for beauty and good writing. […] The author has never been to school. There seems to be no sane reason why she should ever go to one unless she wants to. […] She has the Mozartian calm. She writes as though she were living in that serene abode where the eternal are. It is as it should be. That is where she lives and where she takes us.

Excerpts from Lee Wilson Dodd’s long review (In Arcady), published in the Saturday Review of Literature on February 19, 1927.

This strange, delightful, and lovely book was written by a little girl as a present for her mother [...] This is very beautiful writing. But there are moments when, for one reader, this book grows almost unbearably beautiful. It becomes an ache in his throat. Weary middle-age and the clear delicacy of a dawn-Utopia, beckoning... The contrast sharpens to pain. One closes the book and shuffles about doggedly till one finds the evening paper and smudges down to one’s element—that smudged machine-record of what man has made of man. Of man—and therefore of childhood! […]

176 Armory Street

New Haven, Connecticut

February 23, 1927

My dear Mr. St. John:

No words can describe how glad I was to hear that you will be in New Haven. I was quite beside myself with glee. Now you boil everything down to plain facts, it is a long, long time since we have seen each other and talked. Last summer has been gone a long time, and that was not a very thorough visit, anyhow. On Saturday I am free from all engagements, and I shall certainly keep it clear for you. When you arrive in the city, telephone Pioneer 5696, and we will make arrangements. My study is, you know, a temptingly quiet place for a good out-and-out talk.

I have my snowshoe trip to tell you about, my experience with the radio, my pirate tales, an interesting friend of mine (a little younger than I am)—and loads of other things. Please don’t change your plans!

We shall be exceedingly glad to see you, and we all send love.

Your friend,

Barbara.

176 Armory Street

New Haven, Connecticut

February 27, 1927

Dear Mr. Jones:

I was glad to know that you liked my book; your review was delightful. That paragraph of The Sea that you quoted was the same one quoted from the New York Times. It is odd, but that place has always been one of my favorite bits, too. I always had a great deal of fun describing fishes.

I don’t blame anyone for not being able to pronounce my names. It took a long time for me to settle into any definite spelling of them at all—they seemed to defy all attempts at writing down.

The mystic art of inventing and contriving such oddities is lost to me now.

Your friend,

Barbara.

P. S. I was especially glad to hear that Eleanor liked the book. I wonder if she likes pirates. I am very fond of them myself, and have been writing stories on pages of gold with letters of pure bright blood! B. N. F.

176 Armory Street

New Haven, Connecticut

February 27, 1927

My dear Mr. Oberg:

This is simply [a] hurried note in the midst of my business, to repeat the invitation which I gave on last October. Can you not plan to come away to N. H. on next Thursday, March 3rd—to stay over the week-end? We would all be very glad to see you—and I’m sure the butterflies need some talking over!

The reviews of my book are fast coming in, and perhaps we can find some time to file them up. All the reviews I have seen so far are very favorable, and it is interesting to keep them.

There is much to tell.

Your friend,

Barbara.

A letter from George Bryan from around February 1927.

Cartagene de las Indias

Nueva Granada

Dear Peter:

I know not whether you would much enjoy this place. The roadstead is indeed large and fine, and has at its entrance a goodly island—called, in the outlandish tongue common in these parts, Tierra Bomba. Seen from the water, the town is sufficiently handsome; for the beholder notes, first, gray walls of a prodigious thickness; then gray houses with roofs of red tiles; and back of these, hills of a considerable height, rising in a green ring.

But the spot when better known is less admired. The climate is by no means healthful. Great heat prevails, and neighboring swamps exhale vapors that are not at all salutary. Water for drinking is obtained chiefly from cisterns that have been built upon the town walls; in these cisterns the rain-water is caught. The streets are wretchedly paved and for the most part wonderfully crooked.

The Spaniards have managed this port as they have managed their other possessions in the region—that is, with the purpose of extracting all possible for their own enrichment and with no care whatsoever for the right administering of justice or for the welfare of the inhabitants. It would surprise you, my friend, to know how much treasure was hoarded here in the old days; and surprise you yet more to know how much was taken hence by some of the buccaneers in those fierce times of plunder of which I formerly told you.

These times are long past; and I am here not to land with a storming-party under cover of darkness but merely by way of a visit of the most peaceable nature. A brief season of leisure thus falling to me, I have been reading with the deepest pleasure the volume that I received from you and that was stowed in my sea-bag when I made ready for this journey. I now discover that the book is by none other than yourself. Upon the page dedicatory the initials J. H. are boldly printed. This is a high honor, forsooth, for one who once upon a time was in fair danger of swinging at Execution Dock!

On numerous pages do I find matters that you often have mentioned to me; only here they are given with a particularity and a smoothness belonging to the written word. Nor rarely do I fancy that I discover myself in surroundings and situations with which you and I in company were aforetime familiar. Unless I greatly err, there is much of yourself in this Eepersip—a name that I never encountered among the various peoples I have known on either side of the Atlantic. At times I follow you, I fear, but haltingly and laggardly, as I followed you in many a pas de deux under northern pines. But I nevertheless do seek to follow; and as I follow, do actually seem at times to float clear of earth and out into the sunset.

Our ship remains here until its captain has completed certain business. How long that may be is not yet determined.

Yours,

Jas. Hook

Bertha Mahoney’s review was published in the February 1927 issue of the Horn Book Magazine.

176 Armory Street

New Haven, Connecticut

March 7, 1927

My dear Miss Mahoney:

This morning I received two copies of the Horn Magazine, sent from Daddy’s office at Knopf’s. It was a perfectly lovely little review of The House Without Windows, and I appreciate it very much. It was a beautiful idea to put Dorothy Lathrop’s little Christmas card in. I have thought before of how appropriate some of her fairy pictures are.

I was also glad to see that you had printed my funny little door-slip. At any rate, I was glad to see that you liked the book: my only suspicion is that it may start running away among young children, and consequently make me a lot of enemies. I already know of one little child who was tempted. Her father wrote to me about it!

Your friend,

Barbara Follett

176 Armory Street

New Haven, Connecticut

March 7, 1927

Dear Mr. Jones:

Until now I had not realized what my book is going to do for the world. But now it seems that it is going to make enemies for me instead of friends. But tell Eleanor to cheer up and finish the book. I have many plans up my sleeve for an Eepersipian escape, and I should be very glad to have a comrade—especially Eleanor.

Lake Sunapee in New Hampshire—where we go for the summers—is a place where one may very well play Eepersip. The small Twin Lakes are entirely surrounded with unexplored woodlands (or, at least, unexplored by everyone except myself) and hills, and very swimmable sand-beaches. It would be just the place for a rendezvous and head-quarters.

But tell Eleanor she must not go without me. I know all the tricks. You see, we shouldn’t be entirely wild—we should be lightly connected with civilization, but I think our Lake Sunapee life would content Eleanor. I am out and across the hills from dawn till sunset.

My knowledge of pirates is rather limited too. Perhaps it is just as well—perhaps that is why I am so fond of them. My pirate learning comes from Peter and Wendy and Treasure Island. John Silver was a marvelous kind of pirate, because he could pretend to be so sublimely innocent. Billy Bones was different, but, somehow, I am exceedingly fond of him, too. The only real trouble with Treasure Island is that Long John should have been able to escape with his gang of rum-and-gold-lovers—with Flint’s treasure in the ample hold of the Hispaniola (as he first intended). Of course, Jim Hawkins should have become a fascinated worshiper of John Silver’s methods, and should have been converted, as Silver wanted. Then the doctor and the squire—also the captain—should have been slain or marooned. Somehow those three were not the kind of persons who should have become the possessors of that gold.

But I am not trying to teach anything to Robert Louis Stevenson.

Your friend,

A rare interview with Barbara, published in the March 13, 1927 Hartford Daily Courant. I’ve cut almost all of the long article—Peter Pan’s Sister Writes a Book—while keeping Barbara’s and her mother’s words.

“What studies have you preferred?” “I like Latin best.”

“Do you read any other language?” “A little French.”

“And next to Latin?”

“Possibly history. In this I have read and read again the stories of the founding of America and the war of the Revolution. Just now I am all wrapped up in the life of Joan of Arc, especially with the historical setting in the fifteenth century.”

“What other studies?”

“Natural sciences. These and their application fascinate me.”

“Does your mother conduct your recitations?”

“Yes, in a general but not a formal way. She gives me problems in algebra, natural history or science and she hears me recite my Latin declensions. She assigns me short stories to write and I have written several. My recitation hours depend somewhat on how busy Mother is.”

“Did you ever try to drive an auto?”

Barbara’s eyes flashed scorn at this suggestion of twelve-year old activity.

“No,” she answered. “I never even had a bicycle. But I love to walk. It was not many weeks ago that I walked twenty miles in one day and have walked over the Franconia range in the summer. I love swimming and I have swum half a mile at our summer home at Lake Sunapee.”

“What authors do you read most, Barbara?”

“Shakespeare, Shelley and Walter de la Mare. I like to read the old authors again and again and I have read and re-read many of Shakespeare’s plays. I have always been charmed with “The Treasure of the Isle of Mist” by W. W. Tarn. “The Three Mulla-Mulgars” by Walter de la Mare, I have read again and again.”

“Are you interested in music?”

“I take piano lessons from Bruce Simonds and violin lessens from Hugo Gortshak [sic]. I have been going to concerts ever since I was six years old.

“Are you going to college?”

“No plans have been made for it. I have always enjoyed my home life and my studies at home.” Which shows that Eepersip, Peter Pan’s sister, has grown up, a thing Barrie never permitted Peter to do.

“Barbara’s education,” explained Mrs. Follett, “illustrates the advantage of not being put into groups. Much creative ability is killed by the modern school. Barbara has been given every chance for expression, and she is taking advantage of them all. Children have much more to say than opportunity is given them to express in the school room. We have tried to allow Barbara a full and free expression. This child has had leisure and tools to work with in her language and thought. She has used both in writing the book. She has never been bored by the things that bore other children.”

Then Mrs. Follett took up the question of a college education where Barbara had left it.

“Selection of a college offers another set of problems,” she said. “Some persons are not so fond of a college course for their daughters as they are. We, Barbara’s parents, do not care much just now whether she goes to college or not. Whether she goes will depend upon conditions that develop later. If she wishes very much to go, she will go, but we shall not decide that for the present. If she shows signs of creative ability, I would not urge her to go for fear of affecting it unfavorably. If she turns out to be without initiative, we may have to send her. At present we feel there is not value enough in a college course for us to wish to force it upon her.”

Brookfield Center, Conn.,

March 14th, 1927

Dear Peter:

Your picture in the paper was mighty pleasing, and I recognized not only you but the setting; but were you really reading proofs?— and do you actually aspire to be a pirate? As Togo, the Japanese Schoolboy, said: “I inquire to know.”

I got a copy of the Wilson MacDonald book some little time ago, when the other Wilson spoke most highly of it to me. It seems to me quite worthy of the praise he gave it. I have read chiefly in the part called “The Book of the Rebel.” “Exit” in “The Book of Man” is a fine variation on an old theme.

By the way, did you ever ask yourself whether that review by Elinor Wylie told you much about the edition she was supposed to be reviewing? Didn’t it seem to you to be altogether too much about somewhat irrelevant things—especially about E. Wylie and various experiences of hers? She had been asked to tell us of a new and important (possibly the definitive) edition of the poet—an edition that most persons will be forced to see in libraries, if they see it at all (so costly it is); and I confess that she left me with no particular idea of the distinctive character and peculiar merits of it.

Thanks for the alphabet (you know what alphabet).

Jas. Hook

176 Armory Street

New Haven, Connecticut

March 15, 1927

Dear Mr. Dodd:

I should have written to you long, long before this, if I had not been confident of seeing you and having the satisfaction of a private talk with you. Your review was perfectly lovely—it made me twice as happy as the others, though they were all favorable. It pleased me boundlessly to see you noticed my “daisied fawn.” For, though I have never seen a young fawn, I think they must look like a daisy field in full bloom.

It seems very strange that I should have written so much about deer without ever having seen one alive. That is, up to a few weeks ago, when I went north to Lake Sunapee with a friend of mine. We stayed there several days, and, on one of our marvelous excursions over to a large game preserve, we encountered a herd of deer, soft-eyed, half-wild does, and feather-antlered bucks. I remember one small buck in particular, who leaped over a fence before our eyes (a fence much higher than he), first throwing up his delicate front legs, and then making his nimble heels “kick at heaven,” as he landed almost silently on four feet of crusted snow. He was like a fairy, a real fairy, even if it is rather out of the ordinary to compare a quadruped to supernatural beings.

Never have I seen anything half so amusing as the antics of young kittens—I used to love to observe the various stray ignoramus cats we possessed at one time—that is why Snowflake is developed to such a great extent.

But I think we need a long afternoon to talk it all over.

Your friend,

Barbara.

From Lady Mary’s Letter in The Star (Wilmington, Delaware), dated March 27, 1927.

Another Infant Prodigy Produces a Novel

There are so many infant prodigies in these days that people almost have ceased to remark them all.

The latest is Barbara Follett. […] As a child lover I shall read the book, of course. But the work of prodigies often appalls when I examine it; usually these overbright youngsters amount to little later on!

Alice Carroll Moore (1871-1961) was head of children’s library services for the New York Public Library system and was probably the most important children’s book reviewer in the country at the time. Her essay, When Children Become Authors, was published in the New York Herald Tribune on March 27, 1927:

[…] I can conceive of no greater handicap for the writer between the ages of nineteen and thirty-nine, than to have published a successful book between the ages of nine and twelve. [...] What price will Barbara Follett have to pay for her “big days” at the typewriter, days when she rattled off, we are told, four to five thousand words of original copy at a speed of 1,200 words to the hour, producing at the end of three months a complete story of some 40,000 words. I have only words of praise for the story itself. […]

Columbia’s copy of Barbara’s response is an edited draft.

176 Armory Street

New Haven, Connecticut

March 28, 1927

Dear Miss Moore:

It surely is very rash to slam down into the mud a childhood and a system of living that you know nothing about. There are things in your article of the 27th that are plain mistruths, which I feel the need of correcting. You write positively as if all children were alike, as if all children desired the same surroundings, as if they all liked the same things. Children are as different from each other as grown-up people; they are even more insistent in their variety of tastes; and a great deal more hurt when things do not go as they like. You say that you “can conceive of no greater handicap for the writer between the ages of nineteen and thirty-nine, than to have published a successful book between the ages of nine and twelve.” And is that true about everyone? Why should it be true at all to an intelligent person? If you think it makes me feel vain and self-conscious to have published a book, let me say that that is untrue: I wrote the story in the first place because I wanted to run away, but, realizing the impossibility of it, I made someone else do it for me. The book was not written to be published—it was written for the sheer joy of writing. I am very much amused at the favorable reviews which are being written—I do not take them at all seriously—but I do take seriously an article which distorts into a miserable caricature my living, my education, my whole personality.

You also said: “Children need the companionship of other children”—but you seem to take it perfectly for granted that I do not. What made you think that? For I do play with other children, and up to a certain point I like it. It is undeniable that I do not go to parties and social events as much as other children do—I do not even play with them as much as other children do, but that, from my point of view, is not a forfeit. Neither am I forced to stay away from them. I do so because I wish to—it is by my own free will.

There are countless other objections to going to school, but with me the chief of them is this: if I went to school, where would I get the time for the violin and piano music that I enjoy so much; where would I get the time for comfortable reading of good books; where would I get the time for the writing which gives me joy more than almost everything I do? If I went to school I should have to spend the afternoon in weary “home-work.” I should be able to write only during the summer months when I love to be outdoors and alone, and I should be doing hardly any music at all.

My life is very different from what you make it out to be: you write as if I was tyrannized over and coerced to be alone, coerced to write, kept away from children by main force. And that grieves me because it is so strictly untrue. It is also an insult to my parents.

Perhaps the most painful thing in the article is your absurd idea that I take a “professional attitude toward writing.” That is so untrue that I am ashamed even to look at it—ashamed that a supposedly intelligent person should say so much about a thing she knows absolutely nothing about. You have no reason on earth to suppose that. As I said before, I wrote the story for the sheer joy of writing, without taking the smallest glimpse of the “professional” side of it.

If you had read the book from the right stand-point, nothing could have made you say such abasing things. The book is an expression of joy—no more—and to a careful person it should be an expression of my home-life as well.

Barbara Newhall Follett.

Eleanor Farjeon (1881-1965) wrote the words for Morning Has Broken—a song covered many years later by Cat Stevens. Her review was printed in London’s Time and Tide on April 25, 1927, about when THWW was published by Knopf in London.

This is an enchanting book. I will be brief with explanations, which are, however, quite incapable of explaining it. The tale is a child’s dream of childhood, as it is and as it might be; and it is the work of a child of nine, rewritten, because it was destroyed, between the ages of ten and twelve. So the tongue of the dream is that of an age slightly advanced beyond the age in which the dream was created; but such nearness of speech and of conception can never have happened before in a work whose whole concern is childhood, and the radiant delight we lose as we grow older. Barbara Newhall Follett found her voice before she had lost anything; the book is bathed in a magical light which we older ones try to remember, or recapture, or assume. […]

I do not think the perfection of this books is an accident; I have seen charming and amusing things written by children who in later life did other things; I have never seen a piece of writing by so young a child which made me certain that it was written under the influence of that movement which makes poets write they know not how. What will happen when her more conscious mind begins to direct what Barbara Follett writes, I do not know; but that she will always have to write I am almost sure; and if, in each age, she can produce something as true to her immediate experience as this, she will have a wonderful record. […]

A letter to her father with an ominous opening line. The quote in the middle (“up to the pig-styes...”) is from Rudyard Kipling’s How the Leopard Got His Spots.

176 Armory Street

New Haven, Connecticut

April 29, 1927

Dear Daddy:

It seems to us that New York must be a sort of Louis XI’s palace, full of snares, temptations, pit-falls, traps, and everything else for enticing and entangling its helpless victims. But now we have a stunning excuse for you to come home:

“The Brat” has a habit of calling at least forty-one times when Helen is in the house, but if she knows that Helen is out, she will hold her tongue. So we have the habit of going out for a walk every evening, as soon as the aforesaid “brat” is in. (She usually, however, has time enough to call three or four times before we are out.) Tonight, having nowhere in particular to go, we wandered over to see what the back-yards of our rich neighbors have developed into. (They are getting to be unusually nice back-yards.) Then a stunning idea occurred to me, and with much difficulty I persuaded Helen to scramble up Mill Rock a little way, and investigate the woods. Besides, I saw a patch of something green up high, which promised mystery. So up we went. The green proved to be a mass of plants which looked like overgrown mint, but among them, and up close to an overhanging rock, a columbine swung two or three red-and-yellow buds.

A long time ago, I had seen columbine up there, but I had never been able to find the place again. This time, however, I land-marked it carefully, and tomorrow I expect to take it up (since it is not a very large plant). But things developed tremendously in the course of a few minutes. There were multitudes of plants with leaves something like the leaves of bird’s-foot violets, but with small yellow buds. I shall watch them. Up still higher we came on to a grassy path, which wound up the ledges. There were high, leafing bushes with graceful streamers up there, on one of which hung a few clusters of a kind of dangling barberry. Down on the right side of the path

(Not a whole garden is so lovely quite

As a prim path with flowers on the right!)

were clumps of leaves which looked as if they belonged to some kind of bulb (long, narrow, pointed), and, on investigating, I found patches of iris growing wild there, with some of them already budded. It looks from the buds like a blue variety. I expect to help myself to some of them. Still farther along on this mysterious path, we came upon masses of white and purple violets, possibly the largest violets I have ever seen. But still farther along was the great surprise of surprises. It was a wall—a high brick wall, with shrubbery showing over the top, and a red magnolia flowering at the foot. Near it were clumps of still another bulb—pale green shoots, not well matured yet. I shall certainly keep an eye (perhaps two eyes) on them. But I have some clue as to what they are, and I believe they are some kind of lily. For amid the shoots was a dried stalk, surmounted with a withered, stiffened, brown flower-cup, which was the shape of a lily.

I intend to make a great many visits, basket and shovel in hand, to this veritable Eden-of-cultivated-things-gone-wild, and I hope you will come along

“. . . up to the pig-styes

and sit on the farmyard rails!

Let’s say things to the bunnies,

And watch ’em skitter their tails!

Let’s—oh, anything, daddy—

So long as it’s you and me . . .”

And there really are bunnies skittering their tails. We saw an adorable small-sized one, as we came down, who flickered his white puff-ball, and he skittered from bush to bush, crouching quietly and melting “Into the landscape.”

The wrens have again tenanted the green bird-house. Sabra was the first one to see them going in and out. Their songs are everywhere now.

The pansies are flourishing nobly . . . . lilacs are still budding . . . . seeds are coming up as well as could be expected . . . . daily I find new lily-of-the-valley shoots . . . . most exciting documents are pouring in from Brookfield Center way, including a delightful review of T. H. W. W., also a great many important hints on the subject of sunset-reading, which I have not come to be very proficient at. The only thing I can think of at this moment that is not progressing, is my pirate story. That is because the time I would otherwise spend on it, I am now glad to spend digging out-of-doors.

I wish you superb luck on your writing (whatever it is), only I am sorry you couldn’t do it here.

You will enjoy my new-found “Mrs. Derby’s garden” up there in the wood. It is very like the woods in which we found so many wood anemones and violets and yellow adder’s tongue, a long time ago. I always have remembered that walk: though I can’t even remember how we got out into the woods, or where we were living. I still remember certain anemone-carpeted glades in those woods, and how we wanted to pick them all. Now, with my new craze, I should probably want to transplant them all.

Sabra is making such marvelous progress in her reading, that I am greatly delighted and proud of her. She picks out the words come, away, play, and run, anywhere in her books. I got her to copy “come away, come and play,” from her first reader on the typewriter. This gives her a chance to learn the little letters. We try to do some every day. She still skips about singing: “It is, it is a glorious ‘fing’ to be a pirate king!” Tonight, as we went down the front steps, we heard: “Yo, ho-ho, and a bottle of ’er rum!” with a terrible accent on the “rum.”

We do hope you will tell us where you are staying. If Sabra should dance out the window tonight, or should be wafted away like Persephone, we couldn’t tell you of it until ————Monday morning!

(The Pirates————1940!)

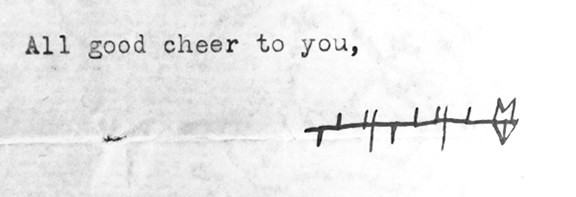

All good cheer to you,

Regarding the treasure buried on Gardiner’s Island in the town of East Hampton, New York, Wikipedia says: “The privateer William Kidd buried treasure on the island in June, 1699, having stopped there while sailing to Boston to answer charges of piracy. With the permission of the island’s proprietor, he buried a chest and a box of gold and two boxes of silver (the box of gold Kidd told Gardiner was intended for Lord Bellomont) in a ravine between Bostwick’s Point and the Manor House... A plaque on the island marks the spot where the treasure was buried, but it is on private property.”

May 7, 1927

Dear Peter:

As you display such keen interest in the matter of treasure, I herewith communicate to you certain information that may prove of service.

The following valuables are supposed to have been found in a swamp on the west side of Gardiner’s Island:

[A detailed list of treasure, including about fifty pounds in gold, included here.]

It is alleged that this treasure was found buried in iron chests, and that it was intrusted to Mr. John Gardiner by Kidd with the reminder that he (Gardiner) must answer for it with his head.

Now, it is possible that further treasure was buried at Gardiner’s Island, either by Kidd or by others. As New Haven is on the coast, it would be possible for you to organize an expedition in the most approved fashion to sail to Gardiner’s Island and search there.

It has also been said that Kidd had caches on the coast of Connecticut and the banks of its larger rivers.

Yours for luck,

Jas. Hook

Hilda Conkling (1910-1986), whose Poems by a Little Girl (which included Mary Cobweb) was published in 1920, wrote to Barbara on May 31, 1927.

[…] “Mary Cobweb” was my one and only friend of mine and I felt very lost and sad when she left me. When I come to think over the likeness between my “Mary Cobweb” and your “Eepersip” I realize that they aren’t so very much alike after all. “Mary Cobweb” was more a “home girl” as they say while “Eepersip” was more for the out of doors. Though I love both equally well.

[…] I do like pirates! I used to tell myself wild stories of being caught by pirates. Of course there was always some handsome gallant that saved me in the end. But I’m sure that your pirate story will have it over mine entirely. What is its title? I wish I could read it sometime. Do you think I could?

lovingly your friend,

Hilda

In June 1927, Barbara sailed for ten days aboard the Frederick H., a three-masted lumber schooner, from New Haven to Bridgewater, Nova Scotia. George Bryan was her chaperone.

[undated, ca. late June 1927]

176 Armory Street,

New Haven, Connecticut

Dearest Shipmate:

As we figger it out, after great maneuvering, the ’hing weighs four lb. ten ounces; 74 ounces in all, divided by half, 37 cents, plus 10 for Special Delivery, 47—total 47; plus 2 for a letter which must be mailed: total 49. So here is 50 cents, and Gow Blass You.

This runs up a debt which could never be repayed, even though heaven should one day in the far future grant me the means, which it couldn’t, with all its power, do, I feel such an inexpressible gratitude, and never, though you live to be a thousand, could any deed outweigh in either words or worth this very climax of all generosity—oh, I have an idea I’d better stop, before I fall asleep in my chair.

The other shipmate,

Barbara.

P. S. One cent tip, as you notice.

Lake Sunapee

New Hampshire

July 14, 1927

Dear Mr. Oberg:

I presume you must think I am dead by this time. Of course, there has been the usual rush getting off to Sunapee. Otherwise I haven’t any excuse at all for not writing to you for such a long time. Oh yes! one excuse.

But that is a long story. Early in June a proud three-masted schooner sailed into New Haven, with a cargo of lumber from Nova Scotia. I went aboard her, climbed many times up to her lofty crosstrees, and out on her high jibboom. I became acquainted with the captain and the crew. A few days before she sailed, I had it all rigged up with a friend of mine to sail back in her with me to Nova Scotia.

Oh! that trip! It was marvelous—it will always be one of the treasures of my memory. We had unusually calm weather, mostly—the sails flapped and the reef points pattered. But when at last we had a wind, we had it hard. It was so hard, in fact, we took down the outer jib and the topsails. The waves were a vivid storm-green, crested with flying foam, and a furious white bone roared in the white teeth of the schooner. Over she canted, far to leeward. Imagine the thrill I had when we sat at table, using table-racks to keep the dishes from sliding off. There were times when even the sailors staggered a bit, walking from aft to forward. At night we almost rolled out of our bunks.

It seems to me, from what little I saw over one weekend, that Nova Scotia is a very beautiful country. And its inhabitants are very friendly and kind, even to strangers.

You should hear me repeat nautical words and phrases and sailor-slang; also, I like to show my knowledge of sailing ships.

I’ll tell you more of this later, but this must be mailed now.

Your friend,

Barbara.

“The Cottage in the Woods”

Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire

July 22, 1927

Dear Mr. St. John:

I think I have never let so many nice long letters come from you without a word from me in the meantime. But, things in general have interrupted other things, and it took me a long time to get “settled” into the ways of civilization when I came back from my sea trip. Before that, I was so excited about the schooner, and going down to see her almost every day, that I could think of nothing else, let alone write letters. Then there was the usual confusion of packing and getting up here—and now, at last, here we be, and it is truly the first spell of real quiet I have had since goodness only knows when.

Do you love the sea and ships, yourself? I do not see any reason whatsoever why you shouldn’t, but, somehow, I can’t associate you in my mind with anything but the woods, and trees, and flowers, birds, mountains. Perhaps that’s because I wasn’t going on my sea-rage when I last saw you, though I remember I was fond of pirates at the time.

Well, I got on a sea-rage all right, and, long before I had seen the Frederick H., I knew quite a bit about ships—ropes, spars, and whatnot. It was the most rash, suddenly unadvised thing I ever lurched forth upon. One day I simply decided I would go. And about three days afterwards I went. Oh! there is nothing in the world more thoroughly delightful than being under sails, the schooner leaning before a north-west gale, the green and foaming waves raging all about, the sails full and bellying out with wind, the howling and whistling of wind through the white canvas, the raging white bone the schooner would have in her white teeth, the far cant to leeward so that we had to use the table-racks, the calling out of “Hard-a-lee!” when we tacked, the bustle of men’s feet to the blocks and sheets; or in a calm for several days, nothing but the swell which rolled you out of your bunk at night, so that she almost rolled water onto her decks, and everything rolling and thumping, doors banging in the cabin, bottles and dishes jingling, the groaning of the booms as they would swing in and out, the billowing and flapping of the idle sails, the pattering of reef-points; and the sailor-life in general, the brief commands of mate and skipper, the nautical words and terms, steering by the light of the binnacle-lamp beneath the stars at night, when the moon would shine full on the sails, making them look like newfallen snow, the very reminiscence of the old sailor-life on clipper-ships, with watches, look-outs, two-hour tricks, the merry yarning of the crew when off duty in the fo’c’sle, the gayness of them all, the carefreeness—it was all just exactly as I had dreamed. Or being in thick fog; when you can’t distinguish sea from sky, everything is a moving, ghostly space that one can see and feel. Or hauling and lending a hand anywhere—on ropes which needed tautening, taking a turn at the wheel, sweeping the decks by the hour for my special friend, the mate, helping the old cook over his meals and his dishes, talking with all the crew—it was my great delight. And I loved to go up in the rigging, too, especially on hot days, for there was invariably a breeze aloft, and you got shade from the vast expanse of the sails—up and up I would go, into the taut ratlines, feeling the life and joy of the ship as if she were a living, happy creature—happy leaning before the wind, happy in the foam she made, her white wings and the furious bone she held in her teeth; up where the taut ratlins quivered a little beneath the strain of the wind, and I would sit on the cross-trees and swing my legs into space.

But do not think that I have forgotten about the mountains. No indeed. I am very eager to get up on to granite peaks again. And so Mother suggested (and I strongly seconded the idea) that you should stop on your way up to Passaconaway, and take me along, and climb a mountain or two with me. For that would be two-in-one—we should have our wished-for visit, and a mountain at the same time—a pretty fine combination, in my mind. Do you suppose that could be arranged? It wouldn’t matter to me what mountain! And it would be delightful if you could stop in this region two or three days, and become acquainted with Lake Sunapee once more.

As for flowers, Hooker’s orchid seems to be pretty well attached to me. I have seen three this summer, and saw three last summer. They are the weirdest, most mysterious looking blossoms I have ever seen, that mystic green, with the two pollen masses of golden-brown, looking for all the world like two eyes in a little green face. The leaves are very curious, too, so shiny, round, and almost leathery. I suppose you are acquainted with the flower.

We have no plans at all for the late summer, and, having no automobile, it is impossible for us to do anything on our own account. But stop here on the way up, anyway, and we’ll make plans then, and see about a capful of mountain-wind, or a shoeful of mountain snow.

Your friend,

Barbara (Sindbad, the Sailor)

The recipient of the next letter was almost certainly a descendant of Benjamin Stimson, who sailed with Richard Henry Dana, Jr., author of the 1840 book, Two Years Before the Mast. The 1911 edition published by Houghton Mifflin had a painting of the Alert on its jacket.

“The Cottage in the Woods”

Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire

July 26, 1927

Dear Mr. Stimson:

The book arrived late yesterday afternoon, forwarded from New Haven, and it carried with it a great mystery, and a great many questions. How in all this world did you know that I am what you might call mad, love-blind, over sailing ships of all descriptions, as well as over sailor-life in the square-rigged period? It has always been (or, not exactly always, but since about last fall), a great regret of mine that I was not alive during the clippers and square-riggers—before the age of steam. But it is too late now—to be sure, I can still go on schooner-trips, and I can still sail in the old row-boat of ours with a mast stuck into a whittled hole in the bow of it—but the old square-riggers have pretty well gone by, at least, in this country.

I can get them back, you see, only by means of books—and books do make things almost as real as actuality. From the very moment when I heard the title Two Years Before the Mast (which Daddy mentioned in a letter which he wrote to me when he forwarded the book up here), I thought to myself: “I think this is going to be a book I’m going to like.” And when I first laid my eye on merely the Alert painted on the jacket, I said: “I’m sure this is a book I’m going to like!”

To be sure, I cannot yet say very much about the book itself, having already read only a few chapters—but what I have read are full of the spirit of square-riggers (somehow it is very different from the spirit of schooners), full of both the hardships and the merriment of sailor-life, full of many little nautical words and terms (and the more I see of those, the better, for I am trying to learn them, full of the very sound of the sea and the whistling of wind through the sails—and it is the more vivid, of course, because it is the actual experience of the author. That is the best part of all.

Since you have been so mind-reading (or, perhaps, heart-reading) as to discover this close relationship between me and the sea, you may also know, through the same magical process, that I have just returned from a ten-day cruise on a three-masted schooner. To be sure you have—for it has appeared at least twice in News and Views of Borzoi Books! And so I thought you might be interested in a very condensed brief account of the voyage, which was a curious one, having both dead calm and a high gale, both sparkling clearness and a fog “thick as mud,” as the crew said.

Well, I had been on a sea-rage all right, long before I had seen the Frederick H. I had been delving into a golden treasury of ship-words and diagrams in the dictionary, and I had really learned quite a little about ropes, sails, spars, etc. And so, when a friend of mine, who had been a sailor all his life, told me that a three-masted schooner had come into New Haven, I lost not a second in getting down to see her. She was lying close to the wharf, and it thrilled me as I have almost never been thrilled before, to look up at her long jibboom and flying jibboom, or up into the mazes of the rigging (which I had secret hopes of being allowed to climb). We hailed the skipper, who was sitting on deck, superintending the work or discharging the cargo of lumber, and asked permission to come aboard. This was speedily granted, and aboard we went, helter-skelter, over the lumber-carts. The first thing I did was to climb out on the spanker-boom, which slightly overhung the water, and walk along it to the very end. The next thing I did was to ask if I might go into the rigging. The captain said I might; only I was not to go off the rope ladder, and I was to “hold hard.” I went, and never stopped until I reached the cross-trees. This was as much a surprise to me as to everybody else, for I had never dreamed of going more than a few steps. There I sat, just as Jim Hawkins had sat in his terrified flight from Israel Hands. I experienced great delight in knowing that I was sitting where he had sat on the Hispaniola! We became well acquainted with the skipper, Captain Read, and before very long it was arranged that he should take me and Mr. Bryan with him, back to Nova Scotia. I will not deny that the first thing I did was to dash upstairs to my dictionary, at full speed, and look up the points of the compass, which I learned by heart. Well, to cut a very long story very short (and at that this letter is getting long enough!) it was the most rash, sudden, unadvised, but most thoroughly delightful enterprise I ever lurched forth upon. Oh! but there is nothing more heavenly than being under wide-spreading sails, fore-and-aft, or square, or anything else, leaning before a north-east gale, the green and foaming waves raging all about, the sails full and bellying out with wind, the howling and whistling of wind through the white canvas, the raging white bone the schooner would have in her white teeth, the cant to leeward so that we had to use the table-racks, the calling of “Hard-a-lee!” when we tacked, the bustle of men’s feet to the blocks and sheets; or in a calm for several days, nothing but the swell which rolled you out of your bunk at night, so that she almost rolled water on her deck, and everything rolling and thumping, doors banging in the cabin, bottles and dishes jingling, the groaning of the booms as they would swing in and out, the billowing and flapping of the idle sails, the pattering of the reef-points; the sailor-life in general, brief commands of mate and skipper, nautical words and terms, the reminiscence of old clipper-ship sailor-life, with watches, look-outs, two-hour tricks, the merry yarning of the crew when off duty in the fo’c’sle, the gayness of them all, the carefreeness—it was all just exactly as I had dreamed; or being in thick fog when you can’t distinguish sea from sky, when everything is a moving, ghostly space that you can see and feel. Then I loved my part of it, too. I was often allowed a half-trick at the wheel, in daylight, or steering by the light of the binnacle-lamp beneath the stars, when the moon would shine on the sails, making them look like newfallen snow, or making the foam whiter and lovelier than ever. I used often to lend a strong hand on the hauling of too slack ropes, or sweep the deck by the house for my special friend, the mate, or help the old cook with his dishes, or just sitting and talking with all the crew. But the best of all was, of course, the rigging. Even on the hottest days there was breeze up aloft, and the vast white expanse of the sails shaded you. You think and feel that the ship is happy leaning before the wind, and happy between her furious white wings, and the raging white bone in her teeth. I used to go up there in good, fresh breezes, when the ratlines quivered a little beneath the strain of the wind, and the sails tugged furiously at the gaffs and booms.

Well, you can see what might happen to the paper supply if I keep on too long at this rate. I have been known to talk three hours at a time, steadily, fast, furiously, about this trip, and then do another three hours the next day, yet never repeat a word! I should be delighted to have a real talk with you sometime, on the subject of ships and sailors.

Daddy tells me, by the way, that you are the owner of a Block Island boat. A sort of small schooner without topsails, isn’t it? Do tell me when you intend to take command of it, for I want to get enlisted in your crew. You will find me a pretty able seaman, all things considered!

Again, thank you for Two Years Before the Mast. I’m sure I shall be just crazy over it, as I already am of what I have read.

Your friend,

Barbara Follett.

Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire

July 28, 1927

Dear Mr. Oberg:

Thank you for your letter; also for Sabra’s birthday cards. She liked them very much, and getting mail of her own seemed to her very important. Young children always do like that sense of independence—of importance—and Sabra does, especially. She had quite a little party yesterday—a two-layer cake, frosted, with four small yellow candles and a black-eyed Susan in the middle, stuck down into the frosting; and ice cream. She was quite excited over everything, and told the whole world that she was “four years old.”

I don’t think I ever had a more delightful experience than the schooner-trip. You now, I had always wanted to go on a large sailboat, and this was the most delightful opportunity. I was not long in arranging a passage, I can tell you! We had fair winds, and no wind, thick fog, and clear—just about all kinds of weather—mingled in with a good, stiff gale of wind, the waves raging green covered with white foam, and black squalls thundering up upon us ominously. The shrill voice of the captain could be heard through the howling of the wind, exclaiming: “Get down the outer jib and topsails, boys!” Fog is a very curious thing at sea. The air is wet, heavy, briny, and you can’t distinguish sea from sky—everything is a ghostly, moving, uncanny space. It has no shape, no outline, no horizon—to hear the boom swing back and forth, groaning, by the hour—the flapping of idle sails, the ceaseless pattering of the reef-points. The mate would say: “I hate to do nothing but sit here, and listen to her flap her wings and shake her feathers!” And that was a true description, too. Well, I might write or talk all day about that trip, and yet never get anyone to feel it. They might hear it well enough, but to feel it would be impossible for one who has not been under sails. Have you ever been under sails? When you crossed the Atlantic—was that in a sailing vessel or a steamer?

In your letter you mentioned going to Boston on business. Couldn’t you turn that business into pleasure, and take the train to Potter Place, and thence by stage up here. The driver of the stage is Mr. Crane, and he would undoubtedly stop at the head of the lane, between George’s Mills and New London. We should love to see you, and I hope you will find the chance to get up here. Of course there are certain disadvantages—for instance, the trip is very long and tiring, as of course you know.

Always your friend,

Barbara.

This letter may have been abandoned: there’s room on the first page for the start of a new paragraph.

The Cottage in the Woods

Lake Sunapee

July 29, 1927

Dear Daddy:

We have seen some most curious and marvellous cloud and sky effects today. In the afternoon, when Mother and I walked up to New London, a thunder-storm billowed up behind us ominously, and we received a spatter of rain, but it swung away to the southward, and, though it was obviously raining pretty hard on Mt. Sunapee and the southern hills, we got only a few rain-drops. The clouds were dark and grey, but very interesting, on the way back: there were ranges of sharp-peaked mountains along the horizon, there were billowy masses of greyish-white clouds in peaks, between which could be seen another and darker cloud which looked as though it might be the sea—that same dismal grey of dark weather. When we got down to the shore of the lake, a most curious range of sharp, steep hills was marching slowly, ever changing shape, over the actual hills, looking very mysterious and uncanny. At the same time the sky was full of long, fluffy tiers of white clouds, lighted up by the sun.

But at the sun’s eight bells, when it was the sun’s watch below, the sky and the clouds were the most marvellous. The tiers changed to pink, and pink mottlings dappled the zenith, while down low in the north-west the white clouds changed into a curious formation of wisps and bays and pools. The curious thing about sunset colours is that, while the changes are almost imperceptible while you watch, the clouds really go through such vast changes of shape and colour that one is amazed because it is so unnoticeable. The upper clouds were pink, and lower down were pools of dark gold, mingled with shadowy tiers of blue. Brighter and brighter it grew, and more and more colours kept showing, until the whole west, clear around to north-east, was brilliant with it. In the north-west was the bright pink, the gold, a burning, metallic gold mingled with the blue; towards the south-west was a long, narrow strip of blue-green sky, looking like a sea with islands, bays, coves, and peninsulas—the upper shore of which was a narrow rim of brilliant gold, above which was a dark blue cloud, and the lower shore of it was a purple-russet-maroon—all those colours intermingled. Higher in the southwest were brilliant golds, russets, pinks, and blue shadows mingled together into an indescribable brilliance, and across which stretched a dark blue wing of cloud, a sharp contrast with the pools of colour. A sea of fires glowed amid the lowest north-western clouds, growing steadily larger and brighter, and, higher in the north-west, there seemed to be a pool of blue water, with golden surf which flung itself high into the air along its shores, and almost concealed it. The blue clouds among the gold changed to a maroon, and the colours along the shore of the blue-green sea grew brighter. So it changed indescribably, until there was nothing left—nothing but wildly tossed about dark blue clouds, with a few quivers of scarlet among them.

An excerpt from the first of several letters from Mate Bill, a.k.a. William H. McClelland, first mate aboard the Frederick H. Barbara had sent him a jackknife for a present.

New York

July th 30 1927

Well Barbara

I Reicived the jack-knife sent I came in hear I had left Bridge water before the knife reach there so they sent it to me here

so now I am trying to think how I am gone to return the gif

we was 16 days coming over hear we had light fog all the way over and lots of head wind I though we was never gone to get here Barbara I am sending your things to you I spoke to the old man about them and he made no offer to send them so I thought I would send them to you […]

“The Cottage in the Woods”

Lake Sunapee, N. H.

August 30, 1927

Dear Jane:

Thank you ever so much for your nice letter about my book. I like to think that some children of my own age like the book, because everyone seemed to think that there was too much pure description of Nature in it for children—not enough story.

A great many things, especially in the third part, “The Mountains,” I have seen and known myself. I have been among “frost-feathers,” and I have watched them form out of driving mist which freezes on to the mountain-crags and is cut and carved by the wind. And I have been on Mount Moosilauke when the clouds broke away and the sun burst out almost exactly as I wrote it.

But all of part two, “The Sea,” is my imagination, for I have never lived by the sea, and I don’t know very much about it—at least, I didn’t at the time. I believe I saw sea-gulls once or twice down at the shore somewhere. Since then I know a lot more about it, and I know that if I wrote “The Sea” all over, I should write it much better. Early this June, I went off to sea in a three-masted schooner, carrying lumber down from Nova Scotia, and going back there without cargo. We encountered all kinds of weather—calm, thick fog, clear, and high winds. I lived “rough,” like all the sailors, and I picked up quite a lot about sailing of a schooner, and I learned how to do things on board—and I saw how the sea looks when the fog is so thick that you can hardly distinguish the water from the sky, and how it looks in a gale, when the foaming waves are high. I wish I could have had that trip before I wrote “The Sea”!

Just now, I am having a great deal of pleasure writing a long pirate story. That, of course, has a lot of the sea and ships in it, all of which I picked up just from those two weeks off in the schooner! Do you like pirates and buried treasure?

Please excuse my not writing sooner. The truth is, I came back from the mountains this year with an infection in my hand, so that I couldn’t use the typewriter.

I should be very glad to hear from you again. Perhaps we can keep up a real correspondence. Again thank you for your letter.

Your friend,

On September 11 and 12, Barbara, Helen, and Bruce and Rosalind Simonds took two long hikes in the Presidential Range of New Hampshire’s White Mountains. I’ve walked these same trails and it’s a thrill to read Barbara’s descriptions. On a clear day in late summer such as Barbara’s party had, the Crawford Path above the trees is particularly spectacular.

September 11, 1927

I think no one could have had more splendid luck than H. and I, in the way of weather! Perhaps it was due to the favour of Firefly, perhaps it was due to the magic talisman I wear at my belt—anyway, I can’t imagine a more gorgeous two days. Wednesday, when we drove up, the haze and clouds were low and thick—when we drove up through Franconia Notch Mount Cannon and the Old Man were clear—but Lafayette and the other peaks of the Franconia Range had vanished in haze. Even the nearer glimpses of the Presidentials, as we neared them, drawing further and further northward—were not glimpses at all! But in the evening, though the clouds were thick on Adams and Madison, at whose feet the house lies, there was a mighty north-west wind, and something sharp and cold in the night air promised good weather. In the morning, it proved to be the most gorgeous day of the whole summer—so they said—for climbing. Also, when we had looked out the window, long after dark, we saw the black clouds scudding along at a terrific rate, brightening with strange silver, and suddenly the moon, lacking three days, rose up, and rode proudly above the peak of Adams. We held a council of war—or, rather, a council of mountains—and decided to climb Adams by the Air Line, a trail branching off from the long Randolph Path.

Imagine the delight of not having to drive an inch before arriving at the trail. It begins practically in the backyard—and one is almost under the peak, which rises grimly above the world, like Olympus. First we ascended through low, open woodlands, crossing several small, mossy brooks and one large one; but the climbing begins almost immediately, and before long we could look back and see the mountains north of Randolph, rolling away and away to the sky. Then we came on to the summit of the first foothill of the mountain, and into forest-fired ground—which seemed like nothing but a path of destruction. Above us loomed gaunt, scraggly trees, which once had been mighty and green; about us were thick, new underbrush, and at our feet sprawled mats of snowberry, growing more thickly and luxuriantly than I have ever seen it, and spangled with pearly berries.

Then onward—up and up! We plunged into ever deeper forests of spruce and balsam, where there were high banks and rocks covered with moss on each side of the path—marvellously soft and vivid green moss. One bit of trail had a high bank on the left, overgrown with young spruces and balsams—growing in the midst of an even carpet of rich moss glowing with greenness, and sweeping, unbroken, down to the path. Then on, then on, and on—forever! For these mountains, rather than being more difficult to climb than some of the southern mountains, are just terrifically long—their spurs seem to reach out for miles and miles. But soon we began to notice a marked change in the luxuriance of vegetation. More and more stunted it grew, until, after passing through a few more banks of moss, we came out on the naked ridge—the bare knife-edge of Durand Ridge, which is the eastern wall of King Ravine. The wind was sweeping furiously across the crags—the bare crags with only little clumps of cranberry and other small mountain-plants growing in their crevices. There were to be sure, occasional clumps of spruce on the milder slopes, where they were growing flatter than juniper—but the great rocks seemed bare, treacherous, jagged. Then we began to have startling look-outs into the huge ravine, cut into the heart of the mountain. I was bolder than the rest, going so far as to venture out upon a crag overhanging space, the top of which was a narrow, pointed rock! Up and up the great Knife-edge we scrambled, and it seemed like a narrower and narrower ridge—between that vast bowl off to the west of us, and the Madison-Adams col east of us. Ahead of us were the two splendid peaks—the grey, rocky, but rounded cone of Madison to the left, to the right the sharp cone of Adams, looming far ahead, with wisps of cloud trailing delicately across it now and then; between them, and directly ahead of us, were the “sky-cleaving,” “eagle-baffling” crags of John Quincy Adams—really part of the main peak. And yet not eagle-baffling quite, for, tacking majestically, with silent wings, against the wind, rode a great eagle!

What a terrifying position to be in! Ahead the impassive walls of the near peaks, on all sides of us sheer drops into ponderous ravines, beneath us nothing but bare crags, behind us space and the blue billows of endless, countless mountains! Oh! no one then could take away from me the feeling that I love to revel in—the feeling of awe, of sublime solitude.

The trail skirted the peak of John Quincy, and began to slowly ascend the peak itself. Still the wisps of mist were floating over it—but they were nothing but thin fair-weather clouds—and the blueness behind us was sparklingly clear. The cone of Madison seemed to grow more and more like a peak—it became steadily sharper and sharper—the ravine (of which we were now skirting the headwall) to grow even more terrifying—if that were possible—and our own peak to grow more mountainous and superb than ever. The rocks which we were now scrambling over seemed nothing but sword-blades and rapier-points—they were jumbled together in a way that made you think they must have been hurled there by some great giant, landing at random anywhere. For they were all either on edge or on point—there was no smooth step anywhere! Madison began to rise surprisingly beautiful from a sea of surrounding blue summits—the Carter-Moriah range rose majestically to the right of it, making a gorgeous colour-background for the grey cone—now grown nearly as sharp as Chocorua. I have seen tawny peaks, dark grey peaks, blue peaks, green peaks, purple peaks, rose peaks—but never, until I had climbed Adams, had I seen that heavenly desolate light grey of the peaks of the Presidential Range (especially its northern summits), when you draw near to them.

Up and up! The wind grew staggeringly strong, and cold! Our hands were numb. The cone became more and more sinister, sharper and sharper as we went on, until, at last, we clung for shelter to the crags of the topmost boulder—before a mountain-wind, colder, fiercer than any I have ever known. The gorgeous thing about views from those high mountains of one range is that the most mountainous things you see are the peaks of the same range—they are so near that you see them in all their glory. Madison was now a sharp grey point below us, the Carters rose in their deep blue to the right, farther to the right was the huge bulk of Washington—a mass of blue-green crags and darksome, shadowy ravines and gulfs—with the carriage-road winding, a white ribbon, up its eastern spurs; further still to the right was Clay, from here nothing but a hump in the shoulder of Washington—farther still, and nearest to Adams except Madison, was the high, rounded hump of Jefferson, curious in that it did not seem grey like Madison—rather it was a brown velvet colour, because of the sedge-grass on it—though there were crags jutting out here and there. Its long spur, the western wall of the Ravine and the Castles, stood out prominently—so did the huge jutting crags—the Castles—along it. Then, to the right of Jefferson, and clear around the hemisphere back to Madison, were blue, far-off mountains.

The clouds had now ceased trailing over our peak—they hung high, and made the sky interesting. The Simondses said they had seldom seen a clearer day—we could easily see Mount Mansfield off in Vermont, and sharp Mount Blue far over in Maine. But the most spectacular were the nearest peaks of our own range.

I believe I forgot to say that, while we were ascending the cone, and while the clouds were still scudding across it, it often seemed as though the clouds were still, and as though the gaunt peak itself were slowly rolling and rolling over, like a great ship in a swell. You could feel the earth revolving—and it was most sinister and uncanny!

But it was impossible to stay long exposed to the full fierceness of the wind, so we floundered down again over those sharp boulders and ledges—down until we began to find little patches of warm grass, and then down farther until we were sheltered from the wind and could look things over. We were approaching the Adams-Jefferson col, and we hoped, if there was time enough, to go up over Jefferson itself. Now, looking back at the peak we had just come off from, it seemed nothing but a dark grey jumble of jags—the peak did not have a sharp form, as it did from still further down.

From the peak we had had two glimpses of delightful pools down below—one—Star Lake—just below the cone of Madison, and the other—Storm Lake—down in the hollow between Adams and Jefferson. Now, as we went down we passed tiny Storm Lake very close—I ran down the grassy bank and peered into it. It is a beautiful little pool down there, in that grassy hollow, looking up at the two ponderous peaks of Adams and Jefferson. From there our peak began to look more and more like itself—it became steadily sharper and greyer, and, by the time we reached the spring at the foot of the cone of Jefferson, it was looming up very much as Madison had loomed before—only higher—more impassible in appearance. First we saw the lower crags and slopes of it, rising gradually from the col, a weatherbeaten grey; then a more level stretch of barren ground, though still gradually rising; crowned with the unbelievably sharp grey peak, against the sky, and making a strange contrast with the deep, deep blue of the Carter-Moriah range, off to the right. It seemed incredible to have peak after peak rising off that way, without dipping below the scrub-line between—to have such a vast stretch of the peak of Adams especially, without a tree upon it. On other mountains I have climbed, when you are above the tree-line, you are practically at the top—here, the most exciting, and the most difficult part of the climb is above the trees.

We ate lunch there, in the shelter of a huge boulder, and gazing up at that glorious peak all the time—or off towards the Carters, or Washington. Afterwards we discovered that it was far too late to try to go up to the peak of Jefferson, but Bruce and I scrambled very hastily up to a large boulder jutting out from the shoulder of the mountain, to see what we could see. From there Adams was even more gorgeous than before—if that were possible—it seemed higher, and a little more distant, so that we could really see it better—it was gaunt and grey and weatherbeaten, as before, and the peak seemed even sharper—even more barren and desolate—and we could, of course, see much better, the flanks of the peak, as they rose up and up from the Adams-Jefferson col. It is needless to say that we could see much more of the Carter range—and they looked even deeper blue, and were even stranger as a background for that sharp grey.