5

Life with Nick (1932-1939)

The following letter from Ed Anderson is perhaps the only one that survives of the probably dozens he wrote to Barbara while she was living in New York. (And, as far as I know, none of her letters to him remains, though I’d love to be proved wrong.) It’s undated, but “Soon, it will be spring” suggests February or March 1932.

Finding much of anything about Anderson has proved tricky. Crew lists suggest that he was born in the U.S.A. in about 1904, his middle initial was probably “S.”, and he was about six feet tall. I don’t even know what “Ed” was short for—Edward? Edmund? Edgar? Edwin?

Foss Pier.

660 W. Ewing St. [Seattle]

Dearest:

When I suggested that visit, I should have added that it be entirely on your own terms. It did not occur to me that it was necessary to say so. Evidently I am something of a stranger to you after all. The reason I asked a definite answer was because I knew it would be either extremely hard or else quite easy and simple to answer it. Under the circumstances I think one can be forgiven a little curiosity. How else could I learn if this reacquaintance of ours is prompted by sincerity or just a whimsical moodiness; a sort of nostalgic doldrum that sends the mind foraging amongst the old curios up in the attic. Those outmoded articles that are set aside when new interests, and new friends cause them to appear old and boresome by contrast.

Your reply to my direct request has strengthened a vague uneasy feeling that your letters are perhaps urged by some exigency of the moment. I have a feeling that all is not quite as it should be. What it is, I haven’t an idea, but this is the impression your words give me. When you say that “the inconvenience and little pain” that would be caused by your leaving now, is also to be considered. I have uneasy forebodings of another problem. Pain and problems; what absurd things to waste one’s life over; I’ve long ago cast such matters adrift, and am much happier for having done so. Thus you find me. If coming to visit me is to cause pain + inconvenience, and fill you with apprehensive thoughts of a ‘stranger,’ why then perish the whole idea. Things don’t seem the same; when you were in Pasadena and I in Honolulu I did not pause a moment, but came without the least thought for inconvenience. I wouldn’t do it now, and so can perhaps sympathize with your unwillingness to do so.

The reason I suggested it be soon, was due to the fact that I have not any definite plans for the summer. I can go North on the Holmes, or I can get a job ashore (at least I was offered one). I rather fancy taking a trip in the cutter this summer, but I’m a little bit afraid to play truant too much, gets to be a habit, and besides I’ll have all next fall and winter even if I do go North. Anyway it’s time for me to decide, and in all probability I’ll go North. I can use the money. Were I able to talk to you I know it would all seem very simple, but writing letters hasn’t ever gotten us anywhere. Of patience, I’ve a very small store; in fact it’s a virtue entirely lost when practiced with women, as you once convinced me. Patience seems to spell insincerity in a woman’s eyes. In fact I think women may even spell it as impotence.

So you see how I feel Bar. I wonder if you’ll understand. Friendship and love are not mere words, yet that is about all we’ve been to each other; just words and ideas, and I’m a bit tired of just that. That is the reason I am not going to commence a long protracted correspondence with you. Nothing has yet been ‘clarified’ that way. All it ever did was to impose restrictions on me, I was so in love with you, that I forgot there were other women. How very quaint and old-fashioned Bar.

So let’s be friends if that’s what you think best, and if you want to come out here, then please come, and if you don’t want to, don’t, but for heaven’s sake don’t use me for psychic experimentation, and try studying my reactions to one impulse rather than another.

About my “ridiculous prejudice, about women wearing pants.” That’s the trouble with a lot of women, confound it. They want to wear the pants. But really! my prejudice is purely aesthetic. Most women are a bit knock-kneed, which is quite as it should be I suppose. Most women also have broad hips, and that’s perfectly alright too. Now let’s pause and reflect, what an incongruous sight, an otherwise perfect woman broad-hipped, a narrow head, etc., garbed in a pair of trousers designed for men; with the cunningest little pair of high-heeled shoes pecking timidly from the bottoms of the self-conscious pants. I cannot repress a groan. When women wear pants the hands are embarrassed, they never find their way into the pockets, as hands should do when idle. Pants on women usually fit too tight for that anyway; I’ve seen women in trousers carrying a purse; that would seem to solve the matter of the hands, but what good are the pockets in that case. Perhaps a pair of pants without the pockets and buttoned down the sides would seem more appropriate. A Mrs. K. wife of the captain of the Commodore came aboard once, resplendent in starchy, well pressed ill-fitting white ducks. Captain B. was away, so I invited her to wait in the cabin. She glanced at the proffered chair with suspicion. My sympathetic glance must have reassured her. She managed to be seated without any mortifying sound of fabric parting. Even the most genial of hosts could hardly have suggested removing the offending strides for the sake of the visitor’s comfort.

Soon, it will be spring. I must then start to work in earnest. I’ve had a shockingly idle, lazy, pleasant winter. Now I’m sort of rubbing the sleep from my eyes. It seems hardly true that I’m awake and writing to you. This letter is rather long, isn’t it? I think Bar that we are making a mistake in writing these letters. I know I can’t help feeling a little helpless before you, even in a letter. How you really feel, I am not sure. I think I’ll steer my own course, and if you think the future may hold something for you & I together, then please don’t hesitate. I’d do anything for you, yet I’m not going to press the point in the face of any reluctance, at least not by letter.

One little word of your last letter offends me dreadfully: “Experimental”!! it has a vivisectional sound and a grubby researchy odor. Makes me think of guinea-pigs and pathologists. Shocking of you to use it. I know what you meant, and I say come or do as you wish; let it be a visit, a reunion, an adventure, or whatever you please, but please don’t call it an experiment. I’m very far from perfect and if you seek faults, they’re mighty easy to find. If you haven’t found the perfect or at least ideal mate these past years, don’t be deluded that I may be that nonexistent specimen. I’m not. So here we are, right where we started, and until you make up your mind, I shall bid you a cordial adieu.

E. A.

In 1932 the Appalachian Trail was in its infancy. It hadn’t been cut nor marked for most of its 2000+ miles between Katahdin and Mount Oglethorpe in Georgia. (The first documented “thru-hike” was in 1948 by Earl Schaffer, although there’s an unconfirmed report of a party of Boy Scouts from the Bronx who may have finished it in 1936.)

It surprises me that Barbara hadn’t already told Alice about the three new friends she’d made the previous summer in Vermont. One of them—Nickerson Rogers (1908-1980), the “amiable lad with occasional unsuspected depths”—had just graduated from Dartmouth. Occasionally Nick traveled down from his parents’ home in Brookline, Massachusetts, to visit Barbara over the winter and spring of 1931-32.

Eugene F. Saxton was editor-in-chief at Harper & Brothers.

Saturday

March 1932

Dear A.D.R.:

You really needn’t feel so ashamed of yourself in the matter of correspondence, since you surely didn’t owe me much of a letter, judging by my last two or three!

You are right when you surmise that I have been rushed and busy—more so than ever, since the beginning of 1932. My life is getting almost crowded, in fact. The job, of course, takes eight hours a day straight out, and everything else has to be jammed into the fringes. Since I can’t satisfy mind, soul, or body with the job, I have to jam into the fringes almost as much as another person would put into an entire day.

You want TALK. Well, I’ll try my best, and as there are a few more news items now than usual, maybe I can fill the bill a bit.

First, Helen’s book is getting to that thrilling point. She has received proof of the illustrations—great illustrations they are, looking like very clever woodcuts—and Macmillan has done a surprisingly good job of the reproductions. But since she will doubtless tell you all about this herself, maybe I’d better concentrate on other things.

The more important thing I have to contribute is that Lost Island creepeth onward, in spite of God and the Devil (represented by various personages, of course!). In fact, I’ve gotten to that delectable point where there remains only about a chapter and a half—or possibly two chapters and a half—to be written. That will complete the first draft. Then to sail into a good thorough revision, editing, chopping, piecing, cross-hatching, weaving, repairing, tearing, rending, boiling, steaming, and general subjection to energy. I think I can have it in Mr. Saxton’s hands—willing or unwilling hands—by June 1 at the latest. That’s what I’m aiming for, anyhow. And I still have faith in the old thing, which is quite a point, you know.

When all this energy is accomplished, I’m going to bat out about three copies, of which two will be passed around among a few individuals. You are going to be one of the fortunate (?) recipients. I shall want your criticism—I mean, if you are willing, and want to give it—rigorous and stern and unsparing. There will be four or five other people, who will probably all contradict each other. Then it will fall to my lot to Think It Over, and do some more pounding. Among these selected critics, I’m going to pick out at least two entirely impersonal ones. For instance, a Professor of English at Dartmouth whom I encountered last summer.

After that job is all completely finished, and the black spring binder reposes under Mr. Saxton’s nose, I’m going to sail into another job I have in mind—not such a lovely job, but an even more important one, because my entire existence rests upon it. It will be the introductory material for another book—a book about an adventure I think I shall have this summer. Woods and mountains. A. D. R., I’m going to tell you about it, and you must rise to the occasion, because I’m terrifically excited over the whole thing.

I’ve gotten together a party of four congenial brave souls—of which I am one (I hope)—and we may add two more members. Then, starting about the middle of July, we’re going to Maine—Ktaadn—Thoreau’s country—and from there we’re going down the Appalachian trail, two thousand miles, Maine to Georgia, camping out, and carrying upon our sturdy backs the necessities of life. It will take between three and four months, and be the greatest release imaginable.

Well, I’ve even higher ambitions than that. I’m not just going to take money out of the bank, leaving a hole, to indulge my pleasure. I’m going to struggle to make the thing pay for itself, and the only way I know how to do that is to write about it. And as I said I’ve some ideas for the introductory materials which can be put into words before ever the adventure takes place. And that’s what I’m going to do after Lost Island is carefully finished. All four of us are very much together on this. We’re going to cooperate to the nth degree, and I think that among us all we’ll succeed. You couldn’t imagine a more congenial party. We are getting together this spring for house-parties at intervals, during which we paw over hundreds of maps, draw up provision lists, talk, laugh, anticipate, and in general have a grand time.

The party consists of an amiable lad with occasional unsuspected depths whom I met last summer when H. and I were living in the Vermont cabin; a pal of his, who has a remarkably good head on young shoulders; and a girl who is really a grand scout, with whom I get along quite beautifully. In fact, we all get along with each other beautifully. No friction anywhere, as far as we have been able to discover. There may be two others added to the Grand Expedition, as I said; and we would like of course to have an elderly leader, than whom no finer could be imagined than Meservey of Hanover—only I’m afraid Meservey of Hanover is tied up.

Well, that’s the general idea. It may crash completely. Nothing is certain about it. But we’re all hoping, and pulling together. We’re all slightly rebels against civilization, and we want to go out into the woods and sweat honestly and shiver honestly and satisfy our souls by looking at mountains, smelling pine trees, and feeling the sky and the earth.

We went up to Bear Mountain this last week-end, for the Appalachian Trail strikes through there, and we explored ten or fifteen miles of that section of it. It gave us a tremendous thrill. I can’t tell you what it meant to our world-weary souls to have our feet on that narrow, bumpy, winding footpath that goes clear from Maine to Georgia, marked out by little silver monograms on the trees, which change to yellow-painted arrows over rocks and ledges. Over Easter we’re all gathering the clan again, for another expedition somewhere. These short trips help us to get personally adjusted and strengthen the congeniality still more. It also helps to give us an idea of what we need by way of food and clothes, and also puts us in training, more or less.

It will be a terrific trip, of course. There will be times when we’ll probably be cold and wet and uncomfortable and grumpy. But we’re ready for that—almost covet it in fact. Pitting one’s strength and personality against the wilds—the greatest sort of opportunity on earth.... Well, there it is. My room is plastered with trail maps even now!

All this time I haven’t so much as mentioned A., have I? Well, I’ve had him in the back of my mind—in reserve, so to speak. Luckily, the C. S. Holmes job holds. I guess he’ll be going north again next summer—the third time. There really isn’t anything else to do, with conditions as they are all over the world, especially along the waterfront. His life is odd and stern—verging on tragic, at times. He feels that now and then, and has down-spells, during which I am hard put to it to be cheerful and cheering. I am pretty sure, though, that next fall we shall actually be together, and discuss everything from moths to meteors, including money and mice and merriment and misery and—but that almost exhausts the m’s I can think of at this Moment. That discussion will doubtless decide a good many points about this universe and the nature thereof. Right now he is a little sad, and alternates between letters about the futility of life with humorous epistles about politics in Seattle and other things.

As for being eighteen—well, I don’t think there is anything especially momentous about that. It doesn’t thrill me a bit.

Your mention of spring makes my mouth water. There hasn’t been much around these parts. In fact, Bear Mountain was covered with snow last week-end, and there was driving mist and it was pretty dern cold. However, one can’t stop the seasons, so I have hopes.

I’m so glad to hear the good news about Elizabeth. What an ordeal—or rather, what a series of ordeals—she has plowed through. Phoebe is apparently still toeing the mark, with her nose much to the grindstone. Darn these grindstones—I mean, damn them. And so B. R. is actually going west in the summer—actually, this time? He west, A. north, I Appalachian Trail. Funny world, isn’t it?

You know, I’m ashamed of myself, but it took me several seconds of puzzle to figure out “Miller.” Then I remembered. Wonderful creature that he was! Supercilious, spruce, disdainful creature!

Thanks for letting me see the two pictures of you and P. in the desert. I return them herewith. They are sweet.

TALK? Will these pages do at all? If it’s egocentric talk you were looking for, I should think maybe this would be a slight over-dose! On the other hand, you are so devoted and the lapse has been so long, that maybe it will be endurable this time. You know, I’m still hoping to see you sometime. I have a philosophy of life—one which has been evolving for many years, but which has suffered interruptions and repressions and smashes. Now it has taken root again— or, rather, I realize that its roots are not dead, but just beginning to be powerful. If it grows and thrives and survives the vile climate of trouble and difficulty and set-back, it may take me to almost any part of the old earth where I want to go. What is this philosophy, you ask? Well, I’m testing it warily, leaning on it cautiously, exploring it tenderly, thinking about it profoundly; and if I come to the conclusion that it’s any good, I’ll tell you sometime. Not until it has proved itself a little, though. I’ve lost faith in a number of things—or, rather, I’ve withdrawn from them the crushing weight of my faith. My philosophy aims now to stand upright. Tree-like....

I expect the next year to decide a number of important points. Beginning this summer. I think this summer will tell me a good deal. Being in the woods, standing on mountain-peaks—time to meditate and dream and get a perspective on life. There is nothing more soul-cleansing than to stand on a mountain, when you are inclined to feel hopelessly sure that the world is 99 100ths mankind, and see that vast tracts of it are blankets of forest and trees, after all! Mountains affect inward matters in the same way—reassure one about inward things in the same way as they do the visible things. So I expect to find out several things during the Appalachian Trail expedition—assuming and praying that it works.

Then, coming back from that to this—the complete contrast, the need for instantaneous adaption, and the fresh perspective on this— these things are also going to tell me a good deal. I mean, I shall be ready then to make certain decisions, about philosophy and about life.

Then I’ll remedy the inner workings of the universe! My love to you and all the Russell clan.

Yours,

B.

150 Claremont Avenue

New York

May 23, 1932

Dear A.D.R.:

There has been a terrific long gulf, hasn’t there? It is hard, when all’s said and done, to keep in touch with people who live thousands of miles away, no matter how much you love them. I do want ever so much to know the news—whether anything is wrong, or anything right, or whatever there is and has been.

Spring! That means leaves and fragrances and warm winds and—an Arctic-bound schooner.

The only really exciting piece of news is that this summer I and three very good genial friends are going to tramp down the Appalachian Trail, which runs over mountains clear from Maine to Georgia, a matter of twelve or fifteen hundred miles. Maybe I told you about that before, though. I can’t seem to remember—it’s all been so deathly long, anyhow.

Helen’s book comes out on June 7; mine is in second draft form at last, and I hope to thrust it bodily under Mr. Saxton’s nose sometime in June. It will be interesting to watch the reaction. It may turn straight up in the air—the nose, I mean.

I have decided that there are a good many big and fundamental things wrong with the world, and that nothing can be done about it; furthermore, that one must revolve quietly along with the world instead of trying vainly to buck it. If you compromise enough—to outward appearances, at least—and if you fully realize what a messy world it is, and are reconciled to certain facts, such as continual change and permanence in nothing—why, then you can have a surprisingly good time. That’s what I’ve discovered anyway. I’m having a better time of it these days than I’ve had for ages—almost approaching gaiety sometimes, in fact.

But I confess to being a bit worried about you and yours. Things seemed so rather shaky and precarious for you anyway—always have, in fact. Do let me know if there’s anything wrong. Not that I could do anything. I may be seeing you before the year is up. Quien sabe? It’s a mysterious life.

I’m going to Delaware Water Gap over this coming Memorial Day week-end—at least, I think I am. In which event I’ll convey your greetings to the general countryside. Oh, the beauty of that country in spring! How is spring out your way now?

My love to everyone, but specially to you.

Your

Barbara

150 Claremont Avenue

New York

May 31, 1932

Dear ADR:

I’m relieved about You, at least, through your last grand letter, although the news about B.R. is anything but good, certainly. I don’t know what to say about that, so I won’t say anything.

And there WAS some good news, wasn’t there? It sounds to me as if the little gods were smiling for a change on the desert. I’m quite thrilled over that. Also, it’s good—damn good—to hear that P. is nearly through. What happens after that? “And Life Goes On,” I suppose. Funny old life, isn’t it? A very devil of a complex circular affair.

The book—this time I mean mine—has suddenly sprung a disconsolate discovery. I find, much to my disgust and up-noseishness, that I shall have to write another chapter to round out the thing properly. My nose is still so much turned up that I can’t get after the chapter yet. Of all exasperating things to find out after you’ve written a book—to think it’s All Done, and then to see some untucked frazzles hanging out the tail end! However, that’s but a temporary set-back. I expect to have the whole thing done before I go away for the summer. In fact, I MUST. I’ll try to get a copy to you, and I want your opinion including all the hard slams you like.

As for the AT (Appalachian Trail) we considered taking along “a second-hand burro,” as one of the boys put it. But after all, there will not be any very long stretches of total wilderness, and we can easily carry enough on our own sturdy backs to eke out during those stretches. After all, the east coast—even its mountains—are pretty well civilized in spots—too much so, in fact. The best parts will be the extreme north and extreme south—that is, the Maine and New Hampshire woods, and the North Carolina country to Mount Oglethorpe in Georgia. We were discussing plans just this weekend, when three of the party got together “Beside an Open Fireplace,” to talk.

Yes, Anderson went north again. He is now first mate of the schooner, and rather happy about that, of course. He is doing awfully well, considering everything. I MAY see him next fall—but don’t you breathe a syllable about that, even to yourself! I’m keeping it a very strict secret from myself. If you know what I mean. I mean there are some things in this world that don’t happen if you so much as admit that they’re possible. Perhaps they sometimes happen if you keep your eyes tight shut and don’t think at all.

Oh, I was in the woods yesterday. I’m sure of it, because I’ve a sunburn. It was beautiful. Light green leaves with gold light breaking through them; wild geraniums, birds singing, a lake to swim in, grand companionship—the wild open spaces—but principally sunlight. I know from that taste of it that I couldn’t by any hook or crook stay here very much longer.

Next month I’m going to spend a short week-end in Hanover with some old friends—that will mean another taste of the out-of-doors. And it won’t be so very long after that before we’re off on the grand old trail! One of the boys sent me a couple of the AT trail markers the other day. I keep one of them on top of my office typewriter, where I can see it all the time. It cheers my soul.

Well, now I’ve got to turn to and tuck the shirt-tails of my story into its pants. Do you see what I mean?

GOOD luck to you—oh, Lord, good luck to everybody! God help us—not whelp us any more!

Yours for sunshine,

B.

The following is from the June 1932 issue of Young Wings: The Magazine of the Boys’ and Girls’ Own Book Club, published by the Junior Literary Guild.

“I’ve Got to Go to Sea Again!”

by Barbara Follett

Everyone who has ever gone off on an adventure knows that friends and acquaintances, especially aunts, have a way of firing difficult questions at you. “What made you want to go in the first place?” “Yes, but where did the idea come from?” (As if anybody knows where an idea comes from!) They want to understand the secret workings of your mind. They are interested in the “psychology” of the thing, and you feel like a rather small beetle under the microscope. If the adventure happens to be a nautical one, you say something about “the call of the deep, you know,” and they appear to be satisfied.

But I did not go to sea the first time because of the call of the deep. That call is very real, and very potent, but in my case it came later. I went to sea for what I considered a simple and logical reason: I wanted to be a pirate. (These matters can’t be explained to elderly aunts, so please keep it a secret!)

That idea quickly smashed, of course. I saw that evil-looking knives were no longer clenched between teeth, and that large gold earrings and red bandannas had gone out of style. Mutiny did not seem to be brewing. It was after this peaceful discovery that something else crept into the picture, much harder to explain or describe. I shan’t try to do so. I shall be content with merely calling it the glamor of the sea. Joseph Conrad is the only writer I know who was ever able to put this into words, as you know if you have read any of his books.

Magic Portholes is the tale of my second sea adventure. It was an adventure of islands and ships and stars and laughter; of tropic winds, sleepy island harbors, pathways of moonlight over the waves, vibrant dolphins in the wake, and . . . you know, I’ve got to go to sea again—oh, any day now! Perhaps I’ll meet some of you there.

Frederic Taber Cooper (1864-1937) was a writer, editor, and teacher of Latin at Columbia and New York Universities. His books include The Craftsmanship of Writing (Dodd, Mead & Company, 1911).

Old Lyme, Connecticut

June 29th, 1932

Dear Miss Follett,

Alas, for all my fine promises about returning the MS of your experimental final chapter within forty-eight hours! I am really feeling very contrite. But the simple truth is that after reading the chapter I mistrusted my own judgment and wanted the whole thing to simmer in my subconscious for a while. And then, after a few days I went down and compared notes with Ethel Kelley—as I dare say she has told you before now—and after that I just serenely and definitely knew that my first instinctive reaction had been the right one. Over the week-end I was camping out in the wilds of New Jersey, where apparently there were no post offices, any more than there were on your LOST ISLAND. Up here in Lyme, it is simpler—just a walk of a mile and a quarter, through blistering heat—and luckily I thrive on heat.

No, whatever you do, don’t use that new final chapter. It is written in a wholly different mood, and even the tone of it, even Jane’s attitude towards her specific problem and toward life in general is altered. It seemed to me as I read that some one else, and not Barbara Follett, had been taking a hand in things and giving her version and not yours. What it all means, if I am at all correct, is that you have already, in these weeks or months since you first drafted Lost Island, grown away from your former attitude and can’t quite get back. We agreed the other day that there is no such thing as finality in human stories; but your original ending was as near a definite, logical rounding out as you can hope for. And at least the work was all of one piece. It had a unity in structure and in style. And my advice is to keep it that way.

Now, if some publisher wants a supplemental chapter, I don’t say it would be a mistake to show the new chapter to him. The book as a whole would remain the refreshingly lovely thing that it is, either with or without the addition. Only I shall always feel that it is more artistic just as it stands.

I shall be down in the city again probably some time in July, and shall let you know. Perhaps you would give me a chance to see you again and talk further about what you have done in the way of a final revision. I have enjoyed our various brief contacts—and if I am likely to be of any service, you will please me very much by freely telling me just how I could aid.

Cordially yours,

Frederic Taber Cooper

Magic Portholes was published in June and reviews were good. Here are excerpts from three.

New York Times Book Review, July 3, 1932

“Mother and Daughter Go A-Voyaging,” by Anne T. Eaton

[…] Here, however, is a travel book of a novel kind, for the author and her daughter, the two “shipmates” who are responsible for “Magic Portholes,” have put into its pages so much of their personality, so much of their own zest for adventure, so much of their love for the sea and for strange new sights, that readers from 12 on will have a delighted feeling of making the voyage with them.

Barbara Follett was the author of “The House Without Windows” between the ages of 9 and 12; when she was 13 she wrote “The Voyage of the Norman D.” an account of her first trip in a schooner. Though Mrs Follett is the chronicler of “Magic Portholes,” the book is Barbara’s as much as it is hers. Reading it, one feels that it is Barbara’s thoughts and Barbara’s feelings that the writer expresses, even more than her own. It is a young person’s book, the older of the two shipmates giving the opportunity of self-expression to the younger one in its pages, just as she did when she made possible the voyage itself. [...]

New York Herald Tribune Books, Sunday, July 10, 1932.

“Girls and Boys With an Adventurous Spirit,” by May Lamberton Becker

If alternative titles were still in vogue the one for Mrs. Follett’s book might truthfully read: “Or, Bringing Up Mother.” This being an enterprise forever in fashion, however fashions of doing it may change, it will be seen that the book has two chances in its favor for an audience larger than usual: it may be read, with entertainment and enlightenment, by daughters and by mothers—I don’t know which will enjoy it more—and it may last over into the future long enough to let the next rising generation of girls know how this one met the age-old urge to run away to sea.

For on its first page fourteen-year-old Barbara—who had already, in her comparatively distant past, sailed with the Norman D and written a book about it—comes down with another attack of salt-water fever. Running away to sea, however, has always meant more than ships or salt water. It was once the great American gesture of the youth movement. Boys could do it—and in New England so many did that not to have a seafaring uncle in the family was to be noticeably out of step—but with girls it was only one of those serio-comic threats whose very unlikelihood shows the hopelessness of revolt. But in those days it never occurred to a girl to take her mother along. It did so to Barbara. It is a wonderful thing for a mother to find that her daughter really wants her to go along—anywhere.

[...] The pictures are striking black-and-whites by Amstrong Sperry, who made the brilliant color end-papers and jacket; altogether a work to catch the eye of any age.

The New York Amsterdam News, founded in 1909 and still in operation, is a newspaper with a largely African-American readership.

New York Amsterdam News, July 27, 1932.

An interesting and vivid account of a year’s adventure by a mother who is persuaded by her 14-year-old daughter to pack up and go to the sea. These two shipmates, as they like to be known, leave New York for the West Indies with very little luggage, a slim purse and a desire to see and go as much and as far as possible. In the words of Jerry, the amiable Barbadian bell boy, the idea was “travel light— an’ go far!” The Folletts do just that before their year of wandering comes to an end.

[…] Their first stop out of New York harbor was Barbados, with its tall native women, carrying on erect heads huge wicker baskets containing everything from crimson colored fish to brown and white chickens, still alive. In a rhythmic voice they advertise the wares for sale, in much the same manner, we imagine, as the Crabman in “Porgy.” These shipmates in adventuring mood trek to North Point, the land’s end of the island, where the Caribbean and the Atlantic come together. The journey from St. Andrews, the last stop of the train to the sea, is a hot, tiresome one, through a miniature desert. On their way back to the railroad they stop at a little shop and to their utter amazement find that it is run by one Mrs. Lucas, who had lived in Harlem some years before.

[…] “Magic Portholes” may be read with rare pleasure. The style is so simple that the book should prove enjoyable to youngsters with a yen for seagoing and exploring and delight even mother and dad.

While the reviews appeared, Barbara and Nick began their Appalachian Trail adventure (their two friends didn’t join them after all). After camping for two weeks on an island in Squam Lake, New Hampshire—letting Barbara strengthen her city muscles by swimming and paddling—they began their journey on top of Katahdin in mid-July, walked and canoed through Maine, hiked over the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and ended their approximately 600-mile journey down Vermont’s Long Trail, reaching the Massachusetts border sometime around Hallowe’en.

“Howie” is Howard Dillistin Crosse (1911-1982), a friend of Nick’s. He would go on to become president of the New York Bankers Association.

Harper & Brothers passed on Lost Island, which would remain unpublished until I transcribed and posted it on my website, Farksolia, in March 2012. I’ve also posted Travels without a Donkey, Barbara’s long account of the Maine section of their journey.

Despite Barbara’s offer, Helen didn’t join them over the Presidential Range.

Oquossoc, Maine

Maine State Fish Hatchery No. 7 (on the grounds of!)

Date (God knows) [August 1932]

Dear H:

You are a brick; you took it like a grand sport, and I sure appreciate it. Thanks from the heart.

I am convinced that it was not a mistake. How long it will last I’ve no way of knowing, but I know that for the time being I’m healthier, browner, stronger, and happier than for years; it is the swellest kind of a life: all out of doors, warm and cold, wet and dry, sunshine and moonlight, fir boughs and sleep from sunset till dawn; lakes and rivers and hills, trails and wild country and long white roads; the feeling of utter independence—all one’s belongings on one’s back, and not too heavy at that—God! what a lot of junk civilization involves!

N. is swell—a grand out-of-doors person. We get along quite beautifully in our—what shall I say?—semi-Platonic way. It’s the best thing one could imagine, and I frankly don’t know of another male creature who could do as well. We intend more or less to stick together as long as it’s good. We haven’t any but the vaguest plans as to how a “living” is to be wrested from the world, but we’re going to try various things, including maybe housekeeping in a cave in Tennessee this winter!

The AT is not marked out at all across Maine; consequently we’ve been having a swell time plunging across the countryside more or less on our own—following rivers via old tote roads, etc. Quite exciting and wild. If you are interested in details of the trip to date (geographically) Howie has maps which N. has been sending to him. These are marked up, and in some detail, including places where we had lunch or stopped for a swim or panned for gold without finding any, etc.

Our home is N.’s little 6-pound tent, but we don’t set it up every night by any means. Sometimes, when it looks as if the weather could be counted on, we just spread out on our fir boughs under the open sky.

I wish you could see N. these days. He tells me that he too is healthier and happier than ever. When on the march he wears only a pair of shorts, and is brown as an Indian—maybe a picturesque-looking red kerchief around his neck. He has about a month of beard, which would look like the devil on anybody else; and I cut his hair, but you can’t kill his looks, that’s all there is to it! He’s getting in pretty good training now, too—a bit thinner and more muscle and stands straighter. Eyes sparkle as ever. Always good natured.

Your letter reached me at Rangeley today. The old canoe we bought for twenty bucks at Moosehead Lake should be waiting for us here— we’re going to paddle across these big lakes. Moosehead Lake, by the way, is about the finest looking big stretch of water I’ve ever seen. We hung about it for a week, camping on grand little islands, etc. Then we took our canoe, the Skeleton, down the Kennebec about ten miles—real white water, and we knowing nothing of river canoeing! Judging by the rocks we hit, you’d think that canoe would be matchwood! Well, she was a battered old veteran Oldtown—we broke a few more of her ribs, but otherwise she’s O.K.! A marvellous craft!

I had a letter from Saxton. Oh, hell! Does anything ever satisfy him? Well, here’s the letter. I don’t see what I can do about it now, except suggest that if you feel like it you might trundle the MS to Alfred K. Also, old man Cooper had a lead or two. He could be looked up via Ethel. But don’t go to wearing yourself out over it, because I doubt if it’s worth it.

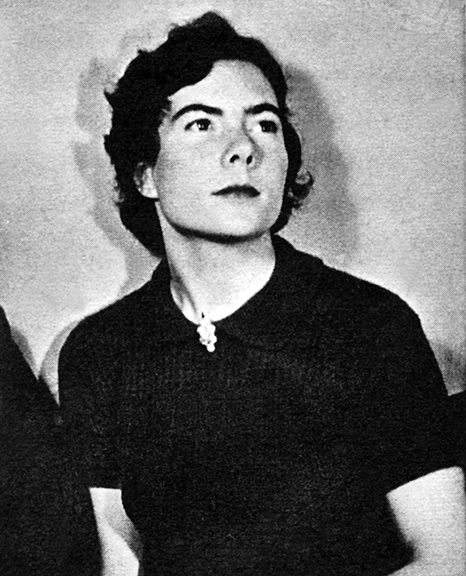

Barbara at camp, 1932

Now listen here, old girl—I’ve a real honest-to-God proposition. You were saying a while back that you were hankering for some mountains in September. N. and I both want you very much to join us at Pinkham Notch and go over the Presidentials with us—a matter of five or six days over glorious mountains during the best time of year. How does that sound? We’ll hit Pinkham about September 12—of course there’s no knowing for sure, but if we depart radically from that schedule I’ll let you know. We want you to be waiting for us at the A.M.C. hut there, where you could stay cheap (something like $2.85 per day, bunk and meals). The procedure is as follows. You carry a light pack (not more than 15 or 20 pounds) including your bedding, clothes, and perhaps a little food. The only expense outside of carfare and board at the hut would be a very small amount for your share of the food going over. As for a pack: if you can’t borrow one from Harley or somebody, don’t worry: we’ll rig you up. As for bedding: three of our* [in margin: *This means your—we have only our own sleeping bags] army blankets would be good—with some blanket pins to make yourself snug. As for clothes: you can have my pants, or you could doubtless get by with an old skirt (how about your yellow jersey one, and mine added to it?) and a sweater, I should think; and my green leather jacket would be good. You want quite a bit of warmth, of course, but also something light to wear while on the go—an old silk blouse, or an ordinary workman’s blue shirt (59 cents!) would be good. I suggest a pair of shorts. They are simply grand for climbing—freedom of action, you know! Having once worn ’em, I wouldn’t wear anything else. You can doubtless get ’em at L and T, although theirs are a little too stylish.

My costume now consists (except when I wear shorts) of ordinary dungaree pants ($1.00) and a blue shirt. As I said before, many people take me for a boy. N. cut my hair off quite short. You’d think it would look like hell, but it’s really an improvement. It stands fluffily on ends, and curls all over the place. It too is having a taste of freedom! And it is wonderfully comfortable. It hardly ever needs to be combed.

But back to the main issue. As regards your footgear: high sneakers would be O.K. if they’re good heavy ones. You can wear mine (they might fit you with plenty of socks). They’re in my bureau drawer.

We’ll take care of all the food question, etc.

Let us know—and do come. It would be grand. We’ll take it all at comfortable speed and have a great time—some good talks, some good laughs, some great old hills. Write me Care of General Delivery, Gorham, New Hampshire. I’m looking forward to it, and so is N. I should think it could all be settled in that one letter. Then I’ll write you again, just to report on progress, schedule, etc., because by the time we get to Gorham we shall know quite definitely when we shall hit Pinkham. N. says that it would be still better to wire you from Gorham, because you should start for Pinkham promptly then.

Here is the procedure getting to Pinkham Notch. The station you want is Gorham, N. H., which N. thinks you hit in White River and Littleton—but check that. Write to Joe Dodge, Pinkham Notch, Gorham, N. H., the hour of arriving, and someone from the hut will meet you. Simple enough, n’est-ce pas? Do come!

As I said before, it is very grand of you to take it all so well. I realize that it messes things up for you terribly, and am sad about that; still, we all have to follow the best thing that we know. Wouldn’t some mountains help a little?

Love always,

B.

Barbara wrote a second letter to her mother from the same mountaintop that she and her father stayed on for several nights in 1925—where she saw frost feathers for the first time. Once again Helen declined Barbara’s offer to join them.

The “letter from the far West” was probably from her father. She enclosed a letter to him when she wrote to Alice on October 4th.

Moosilauke Summit Camp

Dartmouth Outing Club

October 2, 1932

Dear H:

We’ve been up here several days in the Winter Cabin, nursing a bum toe which I acquired. Yesterday—believe it or not—all the little scrub trees were encased in snow, and there were frost feathers everywhere, some six inches long. Washington and the Franconias gleamed like Alps in the sun. There has been all sorts of weather— from specklessly clear days to mist so thick that you could cut it with a knife—we had to take axes and chop holes in it when we went outdoors!

There have been a few interesting people up here, too. Yesterday, for instance, we had a delightful little Englishman (cartographer for the American Geographic). He knows the West Indies, and the Canadian National boats, and he says “Jolly old boat”—it was good to hear, that phrase! We spent most of the time shouting duets and choruses out of Gilbert and Sullivan.

In a few days now we shall proceed to Hanover, and then to the so-called “Long Trail” in Vermont, which should be lovely, though probably not exciting, country. It should be fairly easy going, and there are shelters at convenient intervals. We’re going to stick to this game until it gets too damnably cold—then we may beat it (hitch-hiking) to Tennessee or somewhere. We don’t know for sure when the weather will get too much for us, but I expect not until late October or November. Anyway, the point is: how would you like to join us along the Vermont trail? We’d like to have you ever so, if you won’t mind the cold—it will be cold, of course, some of the time. You will want to take plenty of warm clothes and blankets. One trouble is, we wouldn’t be able to equip you with a pack on this stretch. That would have been possible if you had joined us at Pinkham, but not here. Either borrow, buy, or steal one.

Here are the practical details: write me Care of General Delivery (“hold until called for”) at Hanover (address envelope to Nick, not me: that’s the way we’re handling the mail now). In that letter let me know definitely whether you can get away sometime after the middle of October for about a week or ten days. When I have your answer I’ll write you from Hanover just where, and when, and how, you’re to meet us—probably at East Clarendon, Vt. How does this sound? It won’t be so utterly thrilling as the Whites would have been, but it ought to be fun; we can have some talks and laughs and stories. You can imagine that we’ve got some stories by now!

Did I tell you that I had a letter from the far West? The unrealest thing I ever saw. It simply doesn’t exist.

N. wears well. I don’t know anybody else in the world (at least, of the male sex) whom I would want to be thrown together with so closely for so long through so many variegated adventures. We haven’t even scrapped at all, which is rather remarkable, considering how constantly and intimately we’ve been together since July. I’ve never had such an enjoyable and satisfactory relation with anyone. We’re going to chuck it, clean, when we feel like it, but now it promises to hold out ad infinitum, and it’s grand.

Don’t lose your head or get scared when you see N: the beard is now three months old. The effect is a combination of prophet, Russian, pirate, and genius. Howie reports that friend Casseres has a mustache now—one that “would do credit to a Polish street-sweeper.” I should like to see it.

How’s everything down your way? Sabra, radio, etc.? Did the Sperry brat arrive O.K.? My love to them. Had an awfully nice note from Miss Carney—but Christ! am I glad I’m not there.

N. sends his best. We really hope a get-together can be worked out, though we thought it swell that you stuck to the job so heroically. More power to ye!

Love,

B.

Moosilauke Summit Camp

Dartmouth Outing Club

October 4, 1932

Dearest ADR:

I have so much catching up to do that I’m not even going to try! Someday, though, I’ll tell you the things that have been happening— the curious, joyous upheavals my life has undergone, and the gipsylike ways I’ve been living, and so on.

Right now my object is the transmissal of the enclosed letter to W. F. (which I should be glad to have you read if you care to). It may be that you have no idea whatever of his whereabouts. In that case, merely destroy it, as circumstances are not opportune for writing to him through Helen. If you can get the letter to him in any way, and if he answers it, I want the answer to come through you, as I don’t want just yet to give him the address which I’ll give you at the end of this.

All this sounds terribly complicated and mysterious, doesn’t it? But you see, I’ve jumped many hurdles of late, and want to be cautious. I’ve jumped the whole structure of what life was before: I’ve jumped the job, jumped my love, jumped parental dependence, jumped civilization—made a pretty clean break—and am happier than for years and years. I’ve a new, and I think a better, structure of life, though time alone can tell that!

How are you and yours? I long to know, fear to ask. It has been so long since we’ve been in touch! Write me a word at this address, and then I’ll tell more about everything.

Love as ever,

Barbara

Address mail to: Mr. Nick Rogers

℅ H. D. Crosse

834 DeGraw Avenue

Newark, N. J.

(not me—this will nevertheless be quite private)

Barbara must also have written to Anderson while on Moosilauke: his reply follows.

Richard Charnock’s Prænomina, or, The Etymology of the Principal Christian Names of Great Britain and Ireland (1882) gives the following definition for Auna: “... this female name is thought to be the same as Aine (pronounced nearly ‘awna’), still given, or given till very recently, by Irish-speaking people to female children in the south and west of Ireland, and which he thinks is connected with the old Irish moon-goddess, commonly Anglicised to Anna or Anne ... the Erse word ‘aine’ signifies ‘music, melody, harmony’.”

Box 65

Oct 21 1932

Bar, you wonderful woman, you can’t imagine how I feel today. You think I am pained, or unhappy, then know that I feel quite the opposite. Now I know that everything is real that you are not after all, an ordinary person. Now I know that, had I but dared tell it to you, you would not have laughed at my own ambition, a ‘madder’ one than yours.

I must tell you now. I hate domesticity. I’m afraid of domestic people. I hate daily routine, and dollars and cents calculations; I wanted, more than I want you, to escape all that; the idea was breeding when I met you first. Perhaps you can guess what form my escape would take. I am going to have my own ship and go in my own way to do the things I choose. That is why I am working, for that, and not for the grubby comforts of domestic security. Before I met you, the idea was in a singular tense, then I had wild fancies that you might be a kindred spirit, and understand, but yet I was afraid to put words to it, and when you became efficient and psychological and, as I feared, ordinary, it was still harder to bring it to light. I then hoped that I could convert you to my faith after we came together. Yet it seems that you are as strong an advocate as myself, so therefore I feel as happy as if you had really known, and understood. We shall never grow old now Bar. This talk of love, that word love, what do we mean by it, not what you thought I meant. Poor abused word, with the weight of the whole world bearing down upon it. Happiness, contentment, security, bah, give me freedom. Why do you think I wanted to be definite and frank; because I wanted to feel free, and feel I was myself. Now I do, and I am happier than I’ve ever been before. You terrified me with talk of clothes, and dinners, and responsibilities, that is why I failed to make you love me. We two should have been more careful with that word love. It meant more than either of us realized. Now I know why I loved you, and why I still do, and even if you never see me again, I shall not cease to love you. I do not feel jealous towards your new companion, though I don’t deny that my greatest wish is to have you myself. He can probably take better care of you than I. Yet you are my woman even if you try to deny it. You are life, and adventure itself, and you’re completely wasted on anything else. Perhaps I shall meet you someday, maybe you’ll come for a cruise.

There’ll be no need for talking it over. (In fact what has talk done so far.) Would you come, or would [you] discuss it. Eepersip tired of the forest, and went to the sea, you know. So you must write to me, so that I may find you. Now you really are worthwhile, and to think I grieved over your changing.

Listen Bar, this is terrifically important to me. I want you. A year ago I was doubtful. Do you dare or care to take a real chance, on a real adventure. Think Bar, roll the words on your tongue. Marquesas, San Lucia, or what sounds best. Dolphins under the bow, flying fish, and the changing sky and water. Better than a cave perhaps. There’ll be books to read too, when the mood takes you. Dungarees, and bare-feet, or shoes and skirts, whatever the mood asks. High latitudes or low, wooded shores or coral reefs, nature smiling warm, or nature riant, fearful. This has been my dream, this is why I have wanted you. This is why my woman was so treasured. I do not say ‘please,’ or ‘do.’ If you’re the one, you’ll know, if not, then solitude has no fears for me. The best years of life together. The end painless. No ‘thou shalls.’ Away from the pale ledger-minds; only the task of living to face.

You see, Auna, I’m myself now, you’ve lifted a tremendous load from my mind, now we need not be self-conscious or fearful of painfulness. You think a lot of ‘Dartmouth’ don’t you? Are you sure? Come Bar, tell me, is he everything. Does he deserve all of such a one as you, can I not lay a fair claim to you. Do you think I’m working for its own sake, and saving for its own sake. Open your eyes. Life is not as transparent as you think, nor perhaps as obscure as you may have fancied. Let me rescue you now, from that cave. Step back a few steps, and let’s start afresh, the way we should have started. Let not the dream be too easy of accomplishment, let it be not only today’s but also tomorrow’s. I do not say you may tire, but what of him, may he not. With me it might be harder, but more lasting, I know. Dungarees or skirts. You’re the woman. You’re my woman, but woman-like you’re wondering about happiness, and so you deny me, thinking of the ‘best happiness.’ Put on your cap and coat and come West. Have a talk with me. If D’s real, he’ll understand, if he won’t have it, then be a rebel and come on general principles, and if you don’t like our prospects I’ll see you safely returned, even to him. Surely you can take a month off.

I’ll wire you the fare; the cave won’t disappear in the meantime, nor will he. Try it. Try him, try me. Don’t you think it would be a good adventure. Just to see, and know.

I want you,

A.

[undated, but early-mid November 1932]

℅ Howard Crosse

834 DeGraw Avenue

Newark, New Jersey

Dearest ADR:

You wanted to hear from me promptly—right away, return air mail and all that. But, you see, in the rather odd kind of life I’m living right now, such things can’t be done. When your letter was forwarded to me, I was—well, where was I, anyway? Williamstown Mass., I guess—just in from a week’s stretch of Green Mountains. The next day we pulled out, hitch-hiking. I’m in New York now, at the apartment, but only till about tomorrow. Then I light out again.

Now I’m in Brookline, Mass., clearing up a few earthly details before sailing for a little island off the coast of Spain—if you can believe that! No wonder you are puzzled. The reason I didn’t try to go into any sort of detail in my first letter was that I wanted—well, to sort of feel around first, if you see what I mean.

However, before I go any further with this, I want to tell you how tremendously I was pleased with your news, which is at least as exciting as mine, only in a different way. That is, the good heart sings for you. Oh, how I hope nothing will go wrong this time! And then to hear that E. and M. have had no more devastating catastrophes, and that Phoebe is fairly happy, and that you yourself are surviving so well, head above water and all.

I don’t enjoy going into terrific detail about myself, by mail. It seems so rather brazen and cold-blooded. And I’ve been writing fewer letters than ever. But to put it briefly, New York irked me past endurance, and I had an opportunity to quit it all. I thought about it pretty hard for a while, and then decided that in spite of certain complications, “obligations,” and whatnot, I would chase them to the four winds and take my chance. So I did. I and a comrade escaped to the Maine woods (Katahdin, in fact) and then started off tramping south down the footpath that runs intermittently all the way from Maine to Georgia—the Appalachian Trail. It was a tremendous summer. There were mountains and forests, rivers and fields, sunlight and starlight, fir boughs and birds singing. But it was not only a summer. It will go on.

Those are the brief facts—which, of course, are not a satisfactory offering. You see how hopeless it is to give you a good idea of what it’s all about, and why. Besides, it’s all based on such subtle intangible things—except the boat to Spain, which is fairly tangible. I’ve tossed a lot of things to the winds, of course. I mean, I’m gradually getting to be a fairly “shady” character, but it’s worth it. When it isn’t worth it any more, I’ll change it some how. There’s always a way out, if you have courage—there was even a way out of New York!

Sometime my devious paths will lead me to you. I know that. Then there can be a real discussion, and real understanding. Right now I’m living in kind of a golden ethereal mist, and I haven’t typewritten for a long time, either! So I’m handicapped, more or less. Besides, the things I want to say are too new. They are still seething and surging around in my heart, but they haven’t been able yet to take their shape and wings and fly into the sun. It’s all pretty experimental, anyway. This I know—life is better than I thought. It can continue being good, if one only knows how. I’m trying to learn. I am learning, a little.

Helen has both backed me up and condemned me. Of course, it’s hard on her. A very subtle and complex question of ethics is involved—whether ’twere better etc. I’ve found this out—you can’t arrange your life so that everyone is satisfied, including yourself— unless you are a very uninteresting person. And the break had to come. I’m not claiming I’m right (how foolish it is for anyone ever to claim that he’s right about anything!), and God knows I may end up in an awful mess. Still, all I can do is follow the best I know—take the greenest and most verdurous trail that I can see. If it ends in a desert or a swamp, maybe I can go back and try another one. And that makes a cosmic adventure of if all.

We sail within a couple of weeks, probably. This was quite unexpected and out of the blue—we meant to go to Florida for the winter! I think you would like this person who has been constantly with me since the first of July, and intermittently for about a year before that.

Anyway, maybe I’ll drop you a few lines from Majorca or Minorca or somewhere!

With much love, and the best of luck to you.

Yours,

Barbara

Thanks for transmitting that letter. I’m glad I wrote it, whether he answers or not. Above address holds good.

Nov. 23 1932

Dearest Barbara:

I could not help, a prayer. I love you. I love you. Write, please write to me. The long storm has hurt too much.

Forgive the way I wrote it, it was much earlier; want can exist on hope, for me awhile; if you’ll but say a little “That it doesn’t make you unhappy because I want you” “That it doesn’t spoil a new something” If I would but really know, I would rest, no matter what. But this dreadful thought that we hurt for no reason other than lack of understanding is unbearable. Don’t you see, Dear. I love you, therefore you may trust me.

A word of hope, please, or a word of reason why there’s none; you didn’t go from me, you drifted away. If no one took you, drift back; if someone did. Tell me. You’ve been so vague. You hurt. There’s something of you within me that you left behind. A true word would remove it, and leave me in peace, content that you were happier. If there’s a ray of your affection left, don’t try to kill it, for I love you.

A.

Anderson included a poem with his letter:

A Prayer to Virodine

Oh Virodine from you I pray a miracle

Teach her please a want expressed in me

Send back Auna of the darksome moody eyes

She was not flame, but spread, cool and warm, a russet charm

To match her autumn tinted hair

It seems not fair that I should lose her now

For I have learned of much to give

Sympathy, and knowing wisdom besides just love

Dear Virodine if I may humbly bow before Auna’s shrine

Will you not bid her stir and murmur,

“I only left and had strange dreams awhile.”

She needs so little, yet so much.

We should have a rare exchange

A sort which does not take to keep a captive to oneself

But roams in freedom, seeing, feeling, understanding, understood.

If I’m a spirit, twas her creation, she must not push her work aside.

The cry is need;

To recognize, that here as well an earthly glamour has been too long denied, and threats to turn on spirit and devour.

The counter-point of detail all around, dins in my ears.

Drowns out a grander symphony that yet too softly murmurs.

She must return;

Don’t let her say a “coward” plea

There’s nothing now we could not face, no nothing

She must come to me.

If she was sad, so was I.

If she lost something, so did I.

If something died, twas in us both.

Twas only sorry tact kept us apart.

She says she does not want a nest on ground: And nor do I.

All cluttered round with routine.

Perhaps it was your wish that we should learn thus so

That when together we’d evade more lacerating hurt

The petty gods now strewn away, in absurd posture, facing bolstered up.

From which I turn to gaze at One

I turn to you and ask Auna back.

It is not time for her to go to poppy isle.

Till I am ready too

Oh! place a word of hope, and promise on her reluctant lips.

Some little thing to live upon, or I shall starve.

Bring her to life for me, by sacrificing ‘all’ the wrong in ‘past.’

In late November or early December, Barbara and Nick sailed from New York to Gibraltar aboard the S. S. Rex, an Italian luxury steamer. Also on board was Nick’s aunt, who had her own stateroom in first class, while Barbara and Nick were in third. After exploring Gibraltar and Morocco, the couple took a bus up the eastern Spanish coast to Malaga, where they looked for good walking opportunities. They decided on the island of Mallorca instead, arriving there shortly before Christmas.

Unfortunately, the following letter to Helen is I think the earliest European correspondence from Barbara that survives in the archive.

Farksolia has two of the three stories Barbara was working on while on Mallorca: Mothballs in the Moon, which takes place near Lakes of the Clouds on the Presidential Range, and Rocks, “about me going all over Ktaadn alone.”

Palma, March 20, 1933

Dear H:

You sound as if you were having a terrific whirl, what with radio, articles, lectures, etc. It must have its moment of being fun, even if it is built on air, so to speak. In fact, isn’t it sometimes still more fun because it’s air—about me, I mean. If people knew how thoroughly lousy—but let that pass!

Sorry you misunderstood me about coming over here. I didn’t mean I didn’t want to see you—hell, no—I only meant that I thought you’d be disappointed in this place. It isn’t much, really. And it’s overrun with the wrong sort of tourists. That stuff about it’s being “native,” “unspoiled,” etc., is the sheerest balogney. When such reports are circulated about a place, it’s a sure indication that the place is spoiled, I guess.

Do come across this summer, if you can. It would be swell. What would you do with S.? Our plans are uncertain as ever, but right now it looks as though we’d be getting out of here inside of a month. The Meserveys are in the Alps—we’re considering paying them a brief visit, spending a month crossing France, partly afoot; then we want to get into Germany and tramp about nomadically through all the best parts of the country. That sort of thing is done there—our sort of thing—whereas in Spain they look at you a little askance if you walk a mile.

However, we’ve had a good time here. Met some odd people, had some amusing adventures. You have no idea how much fun it is to be married. I mean, when you really aren’t. You get let into a great deal more. There’s a lot of scandal and intrigue here. We pose as symbolizing solid respectability in the middle of a whirlpool of intrigue! We have agreed that the first requisite of a happy marriage is not to be married. N. introduces me as Mrs. R. with uncanny naturalness. Thoroughly delightful. We get along better now even than when we were over there, as we get to know each other more and more. N. still can make me laugh before breakfast, and he still labors under the pleasant illusion that I am beautiful.

For a week we worked—earned our meals and twenty-five pesetas besides. It was in a pension run (or limped, rather) by two English females—really the dumbest and most frightful people I ever ran across. I swept rooms, peeled potatoes, washed thousands of plates, N. polished shoes, lit fires, chopped wood, mopped floors, waited on table. It was thoroughly a scream. We laughed ourselves ill.

I can speak tolerable Spanish now, when the conversation is about simple little things. I’m reading Don Quijote in the original, and getting a great kick out of it. I had no idea what an amusing tale of woe it is. I’m also studying German grammar—although not very hard yet. I have read some good books, such as Of Human Bondage and Jacob Wasserman’s two-volume thing called The World’s Illusion—a strange, gruesome, spectacular work. Ever hear of it?

We made an excellent arrangement with a young Mallorquin which allows us the use of his grand new business typewriter in exchange for English conversation. So I have got two stories typed. They don’t look bad, especially Mothballs in the Moon. I also dictated to N. one day a fairly complete outline for a story about me going all over Ktaadn alone. I’ll try to get at that soon.

That’s about the sum total of my intellectual activities—except, of course, a prodigious amount of pondering and philosophizing. There’s a lot to ponder about. Life, and the best way or ways of living it. We’ll probably never agree about that, you and I; and I, for all my wondering, arrive nowhere definite; and yet I think I have evolved a curious kind of wisdom that seems to serve. No code of morals, no rules of conduct, nothing whatever—no definite faith in anything— sheer black atheism—and yet I get along swimmingly. Instead of trying to pin myself to something, and sinking when it sinks, I have preferred to swim. When I’m tired, I float on my back and stare at the sky. I’ll be all right that way until sometime an octopus devours me!

As for physical activities. I have swum once—very hastily—sea’s damn cold still; I have danced a little, walked quite a bit. Presently, for the weather is getting good now, we’re going to strike out and tramp round about this island—and then we’re leaving it. There is getting to be lots of sun now. I strip to it when I can, and am raising a gorgeous crop of freckles—honeys, they are—the biggest and blackest yet. Old Nick remains true as steel—says they’re swell and he likes ’em and I’m very beautiful. A man like that is about the best thing a feller can have.

We have moved from the Mallorquin pension where we were. We’re now sharing a little house a few miles outside of Palma, with a rather interesting young chap, a Southerner, with a delicious drawl, boatfuls of nigger yarns and stories from the Kentucky mountains. He has good black eyes and an expressive face. Has been leading a rather dissipated life here, with several women and too much drink. The doctor told him to quit it, so he’s on the water-wagon now and living alone in the house, until we come along.

Regards to “Bug” Clarke. Amusing chap. By the way, he promised to write to me, and hasn’t a bit. Ask him if he’s shocked at me, or what? Tell him I might even answer.

Howie Crosse’s mother died—did you know? Heart. Good for him, in a way; he is free to grow up now and be a man.

No, I don’t expect I shall be popping in on you unexpectedly. We don’t expect to come back till fall anyway, and maybe not then, if we can get a job—in Germany, for instance. I’ve noticed that the feller who publishes the Tauchnitz Editions (English and American classics—very cheap and good paper editions) badly needs a proof reader, and shall look into possibilities.

Do try to work it so you can join me in Germany this summer. Keep me in touch with your plans, and I’ll do the same. When do you think you could get away? There would be one or two conditions, of course. About the details of living, etc. But I’m quite sure there’d be no difficulty over that.

We would go roughing it, but not too rough, with our knapsacks and in pants, visiting the mountain huts, which sound altogether too good to be true. We’ll sun ourselves, and swim, and pick berries, and sing songs, and forget woes and worries.

I guess that about exhausts the things to be said. From now on, I shall try to write a little oftener and fuller. I kind of think there’s going to be more to say from now on. For so many weeks we did little but enjoy café life with our books and friends. The only excitement was when we would get just slightly lit up by a few glasses of excellent sherry or Moscatel, and go dancing.

I adore wine, anyway!

Love,

B.

Sabra’s accident at school resulted in a broken leg. The “Ktaadn thing” was Rocks, mentioned above.

The “Herald article” refers to the Boston Sunday Herald of March 5, 1933. Helen was interviewed on the radio program Herald Headliners on February 28, and a week later the Herald printed a photo of the cast and a story: Mrs. Follett and Barbara Run off to Sea.

I don’t think the photo of Barbara running on the beach with a wolfhound has survived, sadly.

Grand Hotel Alhambra

Palma de Mallorca

3 April 1933

Dearest H:

We are both terribly sorry to hear about S. Poor little kid—what will she do for two months? It seems quite cataclysmic. I do hope the school will help you out with the expense. How about that brick floor, for instance—should a gym have a floor like that?

Of course bring her over this summer. You mustn’t think we don’t want to see you; I never meant to convey that. Bring her over; we’ll all get together somewhere, and we’ll both do anything we can to be helpful. If I thought I could be of any real help at home, I’d consider coming; but seems to me that would only complicate matters.

The weather here is much better now. I am getting color all over me, and have been swimming quite a bit. N. is helping me learn the “Crawl.” As you know, I am as at home in the water as any fish; yet I have never learned to swim properly. I am also developing wind and endurance and muscle; and straightening my shoulders. I am trying pretty hard, and they’re almost all right now. All this is N.’s doing.

This morning your letter came. Today we are leaving, with our pack and a rented blanket, for a walking and swimming trip round the island. Sun and sea and open country. Muscles hardening. Moonlight. Good flowers everywhere. Will tell you about it when we get back.

I have actually started the Ktaadn thing. Semi-humorous in places, partly philosophical, adventurous, with characters in it and quite a bit of discussion about Ktaadn and New England in general. Fairly long, but doubtless cuttable to any desired length. By the way, it would be amusing to have a copy of the Horn Book, if you can conveniently send it, also the Herald article sounds amusing. I’d like a copy; but don’t send the whole newspaper, for we are trying to cut out bulk!

Good for “Bug” Clarke! Sounds like a brick. A humorous brick, too, which is the best kind imaginable.

Did I tell you N. and I worked for a week? Earned two dollars (Spanish wages) plus our meals. In a pension which two foolish English women are trying to run. We swept floors, washed dishes, shined shoes, made beds, peeled potatoes, chopped wood, mopped, dusted, lit fires; and at meal-times N. put on a white coat and waited on table, with an incomparable calm, gentleness, and smiling efficiency. He is a wonder. It was a perfect scream.

My Spanish is pretty good now. I can discuss all the ordinary things with a fluency that fairly ripples at times. When it comes to the theory of relativity, however, I prefer to talk English. I love the Sp. language. It has a good sound. The verbs are conjugated very much as in Latin—surprisingly alike. Latin—my little knowledge of it has been an invaluable help. I get along much better in all languages than persons who haven’t studied Latin. The trouble is, here in Mallorca they don’t speak real Sp., although they understand it a little. They speak a lousy-sounding dialect.

Now do, for goodness sake, get this idea out of your head that we don’t want to see you. We do, and we’ll do all we can to be useful to you. For instance, if you keep us well posted in advance, we’ll try to find places to live cheap wherever you’re going. Our next stop, when we leave here, will be Grenoble, I think, so we can climb an Alp. Or even two Alps.

I have a picture I’m going to send you later—of me in a bathing suit running hard along the very edge of sand by the sea, with good waves in the background, and a marvellous jet-black wolfhound, who belongs to a Spanish soldier, running beside me. One of N.’s best, so far.

Well, I guess that’s all. I’m really awfully sorry about this mishap. You’re spunky, a good sport, a thorough brick. Come on over!

Yours,

Bar

[in Nick’s hand]

Love, Nick

Had a good letter from Normy.

Have met some awfully good people over here.

As Barbara promised, she typed up her shorthand notes about the walking trip on Mallorca and sent them to Helen. They total about 11,500 words. The trip report was not published; nor was No Cobwebs or Ghosts, Barbara’s essay about traveling by sea. I will post both on Farksolia soon.

℅ Am. Express Co.

Conquistador 44

Palma de Mallorca

April 13, 1933

Dear Helen:

Your rather depressed-sounding letter was waiting for me when I got back, just yesterday, from ten days’ walking trip around part of the island. And first let me tell you just a little about that, and then I’ll talk about your problems, and possibilities of getting together, and so forth.

I have about thirty pages of pencilled shorthand notes about this walking trip, which I wrote to you as we went along just because I felt like it, with no ulterior motives. But all of a sudden it occurred to me that it might be pretty useful material. Within two or three days I shall have it typed, and it shall go to you, and you will see what you think.

It occurred to me that a long, entertaining letter from me to you might just fill the bill for you at this time. I mean, it would be an answer to all the questions about what I am doing, and why, and what I am getting out of it, and all that. You know: “Dear Mother:” —a letter to her mommy from the good little daughter, and all that. And there really is some pretty amusing stuff in it, as you will see. Would that sort of thing have any commercial possibilities, in connection with your lectures, radio, or a possible article in a newspaper, or something? Can you use it for anything at all? Could there be any money in it? Of course I realize you can’t answer this much till you see the thing itself, but I just want you to be thinking it over a bit, so you’ll be ready for the thing when it comes through presently.

The personnel of the thing could be easily fixed up. This trip could hardly have been taken by me alone. Two girls, or me and Aunt Edith, could by a far stretch of the imagination have taken it. Nick graciously says that he is willing to be a girl for a while in the good cause. But I think the best solution is to make the companion an old and trusted family friend in the late forties or fifties—perhaps an uncle, or something. That would fit in perfectly.

Anyway, you have full editorial powers over the material. Cut it wherever you like, modify it (remember I wrote it simply as a letter to you!), add to it, arrange the personnel any way you please. I feel almost sure you can make something out of it.

If there is a chance of selling it, there will be pictures forth-coming, too, if you say the word. Nick doesn’t know whether he wants to sell any negatives outright, unless he could get a fairly decent price for them, but he would sell the right to reproduce. And, although we haven’t yet seen the pictures from this particular expedition, I feel confident that there will be some pretty good stuff among them.

Anyway, think it over, won’t you?

If you like the material, and the idea seems to go over, I could think about keeping it up—a sort of series of “Dear Mother” letters from foreign countries.

As to Cobwebs and Ghosts, I’ll try to get at that, too. Thanks for the tip.

And now about you.

We’ve got your problems in mind, and we’re going to continue to have them in mind as we go places—thinking a little about cheapness, good places to live in various respects, schools, etc. And I don’t see why, if we keep our heads and act sensibly, we can’t dope out some very good scheme of life for the summer and through next winter. It is certain that you can live almost anywhere in Europe cheaper than in America. France is said to be more expensive than Spain, and Germany more expensive than France, but on the other hand I imagine you can live ridiculously cheap in Germany if you know how. We propose to learn how. I don’t think I’d recommend Spain. What I’ve seen of it isn’t so hot. France or Germany would be better. What I specially yearn for is to spend the winter in the ski country, and learn to ski. An accomplishment I’m ashamed of not having acquired already.

Of course you understand that Nick sticks to me and I stick to Nick. It couldn’t possibly be any other way. The thing would be, for us to keep house for you. We’re awfully good at that, and at marketing economically, and cooking on charcoal stoves, and things like that. Nick would manage a lot of that in his quiet efficient way, and I the rest; you’d never have to put your hand to a dish, or take up a knife to peel a carrot. We’d take care of Sabra, too, of course—at least, I imagine he would do most of that, and I’d help you with your stuff. We’d take it all quite seriously, as a definite, regular job, to be done every day. I’m glad you’re thinking of another book, and I’d be glad to help all I can with it. I know you may say: “It sounds good, but it won’t go through like that.” Well, there is always the possibility that it won’t, but I think there’s a damn good chance if we all go at it cooperatively in the right frame of mind. Let’s try, anyhow. We’ve talked it over a lot in the watches of the night since your letter came, and we think it’s a good scheme, and advantageous to everybody concerned. If you have any alternative scheme, let’s hear it; only don’t try to get me alone because that won’t work. I have to have him, to keep me good.

Well, I guess that’s about all of that. You asked me about my plans. We shall probably be in Palma about a week more, in order to get some typing done—a lot of typing, in fact, while I have this very excellent opportunity. I want to get this Mallorca material off to you (by the by, Mallorca material is said to be more or less in demand), and the Ktaadn thing, too. Cobwebs and Ghosts, maybe. And Nick has some material to be typed, too. After all that is done, we may retire to a sweet place we know up the coast a way, and rest and swim for another week. Or we may not. But in any event, we shan’t be on the island much longer. After that we plan to go up to Barcelona, across the Pyrenees, and maybe drop in on Ellen at Grenoble. Then Germany. But it’s all a little vague as yet, and if you could tell us anything concrete about your plans it would influence ours. I mean, we can still mould our plans any way you like. We really do want to help you out. And we’ll be thinking about it.