[ 4 ]

Imposition and Bargaining in the Making of the Interim Constitution

We’re going to follow two parallel tracks: the Governance Team will continue to work on details with the Arabs on the [I]GC while I tackle the difficult issues directly with the Kurds. Then all the parties will get together to hammer out an interim constitution that would withstand the stresses of sovereignty beset by a stubborn insurgency. And we need to do all this by March 1….

In this chapter,1 I will argue that at the heart of the interim constitution, the product of the first stage of Iraq’s constitution-making process, was a state bargain. This idea is a clarification, not an abandonment, of my earlier stress on imposed constitution making, which others who once disagreed with me have since made their own.2 The bargaining in question was highly exclusionary, more so than even political participation in occupied Iraq, and the exclusion was imposed. The results of the bargain would never have survived the various levels of negotiation and could not have been ultimately insulated by a very difficult rule of change had it not been for constantly renewed threats, in effect acts of force, on the part of the American occupiers. On the other hand, it is also true that what was imposed was not the Americans’ own initial preference but was the result of a genuine bargain with one agent, the only agent they treated as an equal, the Kurdish parties that controlled the Kurdistan Regional Government and who were more or less completely united during these negotiations.

Below, I will contest the notion that the bargain was a historic compromise between Arab and Kurdish positions. The idea of a genuine American-Kurdish bargain, where the CPA negotiated in effect for Arab Iraq, may imply something like that, so I will respond to any possible confusion and criticism in advance. The position the Americans began with in the negotiations was indeed very close to Arab civic or postnationalist positions (the terms will be explained below). But they abandoned that perspective relatively early, and the deal they made was not a fair compromise between the initial positions. It could still be represented as a fair American-Kurdish bargain—after all, the two sides, understanding all the circumstances and power factors, entered into it freely—but it was not a fair Arab-Kurdish bargain, because Arab positions were abandoned, in their name, by others who would not have to live with most of the consequences. Indeed, this was done without using the considerable threat potential of the American government and the CPA, the factor Arabs in the process relied on to the extent they accepted the two-sided structure of bargaining in the first place.

Thus it would be misleading to treat the central phase of the process of making the Transitional Administrative Law, the process of bargaining over the territorial structure of the state, as mere imposition. It was and remained imposition vis-à-vis the Arabs, but it also involved bargaining with the Kurds. The transformation of the Arab-Kurd relationship into a purely strategic one on which no stable new state structure could be based was one important consequence of this asymmetrical way of proceeding.

Arguing, Bargaining, and Imposing

In general, we must assume the presence of all three forms of coming to a collective decision in constitutional negotiations. Undoubtedly, imposition and bargaining both involve threats and the willingness not to carry them out in return for concessions. But it is worthwhile to distinguish the two categories. Imposition is relevant to the extent that (1) an actor’s credible threats cannot be met by effective counterthreats, (2) threats play a much greater role than promises, (3) the bargaining relation becomes monological rather than genuinely interactive, and (4) the result involves no exchange of concessions. In fact, remembering a warning from Max Weber, insisting only on the inevitable presence of both imposition and agreement,3 we should always keep in mind all three terms. Persuasion (“agreement”) must be present in order to keep one’s own side together, the “friend” portion of Carl Schmitt’s famous couplet, which would become too unstable and prone to defection if based solely on interest, fear, or having a common enemy, or even all three together. Imposition is always present, because no two or more sides are ever completely equal, and the stronger always gets to impose to some extent. As long as there is voting on a final draft, and there should be, the winners impose at least part of their constitution on the losers. The same is true when two or more sides make a compromise that excludes a third or fourth on whom the constitution or at least a part of it is then imposed by a majority or qualified majority. It is equally unthinkable finally that different sides should be able to persuade one another on all issues and that there would be no need for compromise. But it may be difficult to imagine a legitimate process where there is no persuasion at all (at least implicit persuasion concerning the fairness of the procedure itself) if compromise processes are to have any success. There are indeed many issues that lack a single legitimate solution, and there is no normative reason to expect one of the two sides in every debate to be persuaded. But only persuasion can lead to an interactive framework that could be the basis of fair bargaining, and only the latter allows parties to generate a minimum of trust, if not in each other then in the framework, and to regard their compromises as more than simply strategic and temporary.4

Thus there is imposition, persuasive arguing, and bargaining in all successful negotiations, especially including constitution-making processes. Of course, the weight of each element need not be the same. If Elster’s emphases concerning 1787 and 1789–1791 could be rightly put on persuasive arguing and bargaining, in Iraq, according to my underlying hypothesis, everything shifted to imposition and bargaining. Ultimately, there were two reasons for this: the amount of force available to one primary actor, the U.S. government, and the repeated and continued insistence of that actor to accomplish constitution-making tasks according to rigid, artificial, and accelerated timetables. The presence of open force and an apparent lack of time make the use of persuasive arguments a highly implausible way of advancing one’s interests in a negotiating situation. I doubt that at the Iraqi venues of negotiation there was a great deal of arguing in the sense of attempts at mutual persuasion based on principles, but it is difficult to tell given the dearth of records and credible testimony.5 At some of the venues, as I will show, we can assume the presence of persuasion based on participation in a common struggle and the obligations that would arise from that. Even here, the instrumental use of public-regarding arguments was the thing that must have been feared the most, namely that the supposedly weaker party will go public with a story of trust and betrayal. But the overall negotiation process had little relationship to publics other than an engagement in the most crass and transparent public-relations operations. Indeed, again following Elster, both imposition and bargaining were often presented to the press in public-regarding forms (and even imposition was masked as genuine bargaining). Under Iraqi conditions of trust, however, hypocrisy rarely had the desired result. Very likely, on the contrary, even genuine public-regarding claims inevitably appeared to be hypocritical. This is a serious matter, because coming to agreement by using public-regarding arguments that authentically could be presented to the outside as such is an extremely important element of the legitimacy of a constitution-making process. It is also part of the “glue” that makes the actual bargains something more than merely strategic ones that could be renounced at the slightest excuse or opportunity.6

I will on the whole avoid evaluating the few claims of justice on the part of the actors, which mostly dealt with past injuries and their proper contemporary and future institutional redress. As far as I am concerned, all of the sides have suffered enough by now, and many though by no means all of the arrangements they seek (for example, a postnational or civic-national state on the part of some Arabs and bi- or multinational arrangements in the case of many Kurds, if they accept “Iraq” at all) could all be made compatible with the demands of justice, even if in different ways, as long as they were promoted in liberal constitutionalist versions. In my view, there is no single just solution to the problem of defining the demos or demoi of a divided society over a given territory, but it is not the goal of this work to demonstrate that rather obvious normative claim. The various solutions to this and other problems that were to concern the Iraqi constitution makers were, however, greatly tied to the past and present structure of inherited memories, ideologies, interests, and power positions of the various actors. The question throughout the process of constitution making was whether these memories and ideologies allowed actors with diverging interests and power positions to compromise their different ideas about institutional solutions. While it is possible but by no means certain that the particular memories and ideologies made mutual persuasion unlikely, in my view they certainly would have allowed principled compromise solutions if a fair bargaining framework had been provided. In relation to the four pressing issues I will discuss, state formation, government structure, rules of constitutional change, and the relationship between state and religion, there is enough to indicate the outlines of where second-best solutions could have been (and, in the last case, were actually found to an extent). The reason why this did not happen in all four cases and for the overall constitutional package was not first and foremost because of the failure of persuasion, which probably never had a chance, but because of the triumph of imposition and its timetables over fair bargaining.

That at least is my thesis in this chapter. To demonstrate it, I will first try to consider the venues and actors in the processes of making the TAL. Then I go on to discuss, as ideal types, the positions the main actors could draw on regarding questions of state and government formation and where the possible intellectual lines of compromise between them lay. Next, I will describe the actual process of the making of the TAL, moving through the venues and making the case for the centrality-of-the-state bargain amid the various phases. Then, switching perspectives and looking at the TAL itself, I consider the three most important areas of constitution making, where there were sharp divergences of positions, to evaluate whether the outcome should be understood as a historic compromise or ultimately the imposition of the perspective of one side. Finally, after considering the deep legitimacy problems of the TAL and its creation, I will consider Sistani’s final battle against the interim constitution and the provocative but inaccurate suggestion that the Grand Ayatollah actually managed to invalidate, and not just delegitimate, the TAL. I end with a discussion of the failure of state reconstruction in the TAL.

The Venues and the Actors

The Transitional Administrative Law was made in four venues, and people who assume that it was one or the other that produced the whole thing are mistaken. In chronological order, but definitely not in order of importance, these were, first, the ten-member Drafting Committee of the Iraqi Governing Council founded in December 2003, under the chairmanship of Adnan Pachachi,7 which may have actually dominated the process very early and produced at least one draft in January8 but later was reduced to a clerical function. This group, in terms of its power to do anything, was the least important, and we know the least about how it worked. It may very possibly be the case that here initially attempts were made to make principled arguments for positions. It seems, however, that when serious disagreements manifested themselves, the Pachachi Drafting Committee hopelessly deadlocked.9 The second venue, in order of importance, was the Interim Governing Council itself. It is hard to say when exactly this body began to discuss TAL drafts and amendments, probably very late if Bremer’s recollection can be trusted.10 But if the Crisis Group is right, its members attended the drafting committee earlier, and the line between the two bodies was fluid.11 Equally important, the IGC did not have a constitutional secretariat or expert staff to preprocess the issues and were entirely dependent on the other venues to prepare the discussions, materials, and drafts for them, and this was a very serious weakness. There was only one exception to this, the issue of state and religion, where many of the members had comparative knowledge and both settled and sharply differing views. Here the sources indicate, as I will show, that there was genuine discussion and give and take in this body, with the political principals playing direct roles, and even the great power holders, Bremer from within and, the sources say,12 Sistani from without, paid close attention and exercised influence. In my view, however, this issue was construed in largely symbolic terms on whose outcome, as I will show, very little was to hinge in the end, except that one side, the Shi’ite clerics, were to sacrifice a lot of negotiating capital over it.

In my view, two other venues were more important. It is commonly said that American experts drew up the TAL, which was originally written in English, not Arabic.13 This is also how one of the insiders, Larry Diamond, seems to describe it, with two qualifications. First, the American drafters did work on a draft submitted to them by the Pachachi Drafting Committee, and second, they included two important expatriate Iraqi (nonconstitutional) lawyers, Feisal Istrabadi and Salem Chalabi, both members of that committee, with the former beginning his service by translating and rewriting the Pachachi draft.14 Thus there was considerable overlap between what I will call, using Bremer’s language, the Governance Team and the Drafting Committee.15 Altogether, the Governance Team, an informal subcommittee of the Governance Office of the CPA (the latter name aping MacArthur’s Government Section, which sat as a “constitutional convention”), had five members, according to Diamond: himself; Istrabadi; Chalabi; a British foreign service officer, Irfan Siddiq; and an American political appointee, Roman Martinez.16 Very likely others including Scott Carpenter, Meghan O’Sullivan, and unnamed lawyers and bureaucrats went in and out of the group. But there was no constitutional lawyer.17 According to Diamond, they worked tirelessly for many weeks.18 From all descriptions, that could not be said of the other three venues, so it is likely that the actual drafting did occur mostly here. However, drafting should not be confused with making, and the Drafting Committee should not be confused with the overlapping Governance Team, which is what Chandrasekaran seems to do, with Chalabi, Istrabadi, and Diamond as his main informants.19 Thus even if the five-member Governance Team “made” most of the TAL—which it did not, as I will try to show regarding the essentials—this would not make it an Iraqi, nonimposed product.20

From Diamond’s own description, it seems to me that the basically American Governance Team had its actual political influence in the area of governmental structure. While it seems that some members of the group had very strong, well-formed opinions on some subjects, for example Istrabadi in his opposition to any ethnic federalism and consociationalism and Martinez in his opposition to judicial (constitutional) review, these ideas were easily eliminated not as much by their internal debates as by the political and ideological trend of the general proceedings. It was when technical solutions were sought to previously made political decisions that the drafters had some freedom, even if at times they wound up (as in the case of the veto powers of the members of the Presidency Council) going against, whether deliberately or not, the original political intentions of actors who may not have understood what the “experts” actually did. Thus they had considerable power, and they had this power on rather less symbolic issues than the plenary of the IGC as a whole.

Where the five-member Governance Team (and especially the Iraqi Drafting Committee) had no power at all was on questions of state structure.21 “The federalism issue was temporarily quarantined while Bremer and other top CPA officials negotiated directly with the Kurds.”22 That negotiation was to last until the bitter end, and was to be no mere “conversation among friends.” According to Paul Bremer (whether or not these words were actually said), a two-track strategy was decided on early in the game: “We are going to follow two parallel tracks: the Governance Team [his use of this term may have been somewhat different in terms of its personal composition than mine] will continue to work on details with the Arabs on the [I]GC while I tackle the difficult issues directly with the Kurds.”23 These trips to Kurdistan continued from January 2, 2004, through at least the middle of February,24 and there were discussions with the Kurds as a caucus in Baghdad25 and with them alone up until the last day before there was a final agreement on the TAL. One such meeting was also held with the “Shi’a House.”26 The “I” in the Bremer quotation, of course, was not quite accurate, even if it revealed a weakness that the Kurds or their advisers discovered how to utilize.27 Bremer went to Kurdistan a number of times, with either Ron Blackwill,28 the British diplomat Jeremy Greenstock, or two young aides, Martinez or O’Sullivan,29 but there is little sign that he ever took anyone along with even the slightest expertise on issues such as federalism, natural-resource allocation, the conversion of the militias, and governmental structure. On their home turf in Kurdistan, in Erbil or Salahuddin as the case may be, Massoud Barzani and Sami Abd-al-Rahman of the KDP and Jalal Talabani and Barham Salih of the PUK, themselves well experienced in governmental-institutional matters (unlike their U.S. counterparts), had great reserves of expertise to draw on, including a very talented group of American, Irish, Canadian, British, and Kurdish exile experts in law, political science, and negotiation.30

As I have already suggested, these Kurdish negotiations were the most important. This was true first because only here did power and issue significance come together. Elsewhere, the participants of the other venues did not have the ultimate power to decide (the draft committee and the Governance Team) or were not given the time and supporting expertise to really discuss the fundamental issues (the IGC as a whole). The Kurds knew exactly over which issues there could be no compromise, but beyond that they were willing to be quite flexible, in particular regarding Kirkuk and the distribution of oil resources. In return, they expected two things and got three, the last the most important. First, whatever compromise was going to be made in Erbil, it was going to be the compromise, and the Americans were expected to impose it on the rest of the IGC.31 The Kurds themselves were not similarly bound. They could and did try—and this was the second thing they expected—to turn their concessions on federalism into gains on the governmental structure being drafted by the five-person governance subcommittee. And they could and did ask for entirely new things in the final short plenary mode, and they expected the Americans still to support them substantively and procedurally. These actions radiated out from the state negotiations and made the Kurds the dominant force next to the Americans in the process as a whole.

And that outcome was perhaps foreordained by the structure of the negotiations over the state structure. It was only here that Bremer and the CPA treated another actor, or two united actors, as an equal, in a genuine bargaining situation without an attempt to impose or to use threats that could not countered (with respect to the Kurds, the threat would be that of an American or Turkish invasion). While I was not there and cannot say for sure, I would not be surprised if the two sides used real arguments to persuade each other on the basis of common interests, common earlier support for each other, and even shared values, along with, most likely, common opposition to the Islamists, or “Black Turbans,” as the Kurds referred to the Shi’ite clerics. With the historical mistrust of the Kurds and the likely prejudices of the Americans, this could have been a context in which some trust was built.

Much more important was the fact that whereas all other negotiations were multilateral, if highly exclusionary, this process was bilateral. The Americans, in other words, accepted the most fundamental premise: Kurdistan was one and Iraq was one, and the two were negotiating their federation and not, as Galbraith supposedly explained, the ways and means of the devolution of power in a united state, in the form of a new autonomy.32 The operative phrase for the Kurds became “voluntary union between the Kurdish and Arab peoples,” which had already appeared in an article by Massoud Barzani on December 21, 2003.33 Of course Iraq, not having a de facto state, could not negotiate with a quasi-state on an equal basis, and this is why Bremer took it upon himself to deal with the Kurds while “mere technicians” did some drafting with the Arabs. Bremer himself claims that all this was “suggested by several Arabs on the IGC.” Diamond says that it was Pachachi’s idea34 to send the CPA boss to Kurdistan, and if so, the elder Sunni statesman must have assumed that only the American leadership had the power and authority to negotiate with the Kurds.35 Indeed, when (apparently meaninglessly) selected Arab participants were invited to join a meeting in Erbil or when the Drafting Committee went there for a session, nothing much was accomplished.36

But what was at stake was incredibly serious and went beyond occasional Arab presence here or there.37 The Kurds were consistent supporters of a selected rather than elected body to draw up a constitution, and they consistently opposed early elections. This was hardly because their parties needed time to prepare themselves, since they were politically the best organized and most experienced in Iraq.38 What was anathema to them for very obvious demographic reasons was a sovereign body, elected by a one-person-one-vote principle, drawing up a constitution for the whole of Iraq on the basis of even a qualified majority decision. They immediately grasped the significance of the November 15, 2003, agreement, and Jalal Talabani was entirely right to sign it from a Kurdish point of view, despite later criticisms he received for accepting language vaguely having to do with territorial eighteen-province federalism.39 That issue could be and was dealt with later; the choice of the negotiating forum was far more important!

What Talabani or his advisers grasped, unlike their Arab counterparts most likely except for Sistani, was the significance of the IGC under the CPA producing an unamendable interim constitution that would significantly preempt and structure the work of the constituent assembly and the final constitution. But even an interim constitution and its negotiation involved hidden dangers for them. If the process was constructed fairly and inclusively, the Kurds would be only one-fifth of the forces present. Their military strength would be neutralized by the referee, the United States, and could not be used as a threat. Secession was a threat but not a fatal one, unless they could take Kirkuk and the oilfields with them, and the Americans had reoccupied that part of Iraq after its early Kurdish conquest in 2003.40 Secession also risked deep problems with Turkey, especially with Kirkuk involved. To be sure, the structure of the IGC was not fair to begin with. With Sunni exclusion,41 Kurdish strength in the IGC was greater than it would have been in a truly representative co-opted body. But their view on nationality, state structure, and governmental institutions was a distinctly minority view, especially initially. They would have received concessions, but the tendency would have been to grant them cultural autonomy in the context of eighteen-province federalism. So it was crucially important for them but unacceptable to everyone else involved to change the format from a round table of, say, four major and a number of minor participants (major: Americans, Kurds, religious Shi’ites, and secular Shi’ites; minor: religious Sunnis, independents, and other ethnic groups) to a figuratively two-sided table of Kurd-Arab negotiations. This was not possible because it clearly would have incited the resistance of all those who opposed the sectarian redefinition and possible division of the country. But it was equally good to get the same structure via a separate set of negotiations in which the Americans represented Arab Iraq; in fact, as it turned out, it was much better, because of the unexpected cooperative attitude or weakness of this substitute partner.

Once the premise of a special bilateral venue was accepted, it would have contradicted the negotiating situation itself to ask the Kurds to give up just those things that led the Americans to accept them as an almost equal partner.42 Letting the Kurds keep those things, however, made them entirely unequal to all the other Iraqi participants in the negotiations, and it required the Americans to enforce precisely this inequality.

Finally, it was important that those who would have objected most vociferously were kept far from the most important negotiations. This was certainly true for the relevant members of the IGC and the Drafting Committee. Equally or even more important, just at the time that Bremer and the Kurds were bargaining the most intensely, the return of L. Brahimi to Iraq was also being negotiated, and he struck his compromise with Sistani around the time the Americans finalized their state bargain with the Kurds. Because of the demands of international law, UN officials were almost unanimous in their opposition to negotiating and especially altering state territorial structure under conditions of an occupation, and to Brahimi and Benomar, being liberal and secular Arabs, the idea of a division of Iraq on an ethnic basis was hardly appealing.43 They were, however, not part of the crucial negotiations with Talabani and Barzani, though of course in February they could have been included. What they knew of the emerging deal is hard to reconstruct. In effect, however, they were offering a bargain to Sistani based on delaying the free election to the constituent assembly at a time when the very significance of that assembly was being reduced by a deal concerning the state that, having been arranged before the elections, would thus be one less thing over which Iraq’s elected representatives would have decision-making powers. No wonder that Brahimi felt cheated and undermined afterward.44

But the UN could in no way reverse or even modify the result of the state deal. Only Sistani could attempt to do that, and in the end he failed as well.

The State Bargain I: The Positions

Having destroyed the Iraqi state in its territorial and organizational integrity and having contributed to the division of the state’s people on ethnic grounds, the Americans clearly understood that part of the constitution-making process would have to do with state making. Most of their bilateral discussions with Kurds were focused on this issue, and it was these negotiations in Erbil and in the end in Baghdad that decided the question regarding at least the territorial structure of the state. They also touched on, less inconclusively, the related question of the possession of armed forces within the state.45 While the reconstitution of the state’s people as two nations along with protected nationalities was also discussed in the bilateral talks, these matters were handled fairly consensually by the other three venues. Given the territorial structure negotiated by the Kurds and Americans, however, it is difficult to believe that the issue of binationalism (language rights in particular) was as open as it may have seemed to some participants. To understand the connection, it may be worthwhile to briefly sketch, even if as ideal types, the main positions present in the controversy. These positions have particular representatives in Iraq, but they cut across parties and in their pure form do not represent party positions.

Ethnic Nationalism (Kurdish)

The ethnic nationalist position ascribed to many Kurds, usually without further qualification, sometimes to the Kurdish “street” and rarely to a specific individual, periodically surfaces in the statements of main leaders and even some foreign advocates.46 It is based on the more or less correct historical premise that Iraq’s originally patched-together territory has always been the homeland of two major “nations,” both quite recent imagined communities, of which one, the Kurds, have never accepted attempts to “Arabize” the whole territory, despite repression, assimilation attempts, ethnic cleansing, and forced deportation. According to the Kurd ethnic nationalist, it is both a matter of justice and unfulfilled historical promises of the great powers that twenty-five to thirty million Kurds, the largest nation in the world without a state, receive their own nation-state.47 For the ethnic nationalist Kurd, there “always” was a Kurd entity in the sense of a people and a territory, and all it has been missing despite relevant promises was a state organization covering the whole territory and administering the whole people.48 For the ethnic nationalist, here as elsewhere, ultimately there is a choice only between (1) Arabic (and Turkish) ethnic nationalism along with the repression and even elimination of the Kurds as a people and (2) Kurdish ethnic nationalism. There is no room here for multiple identities, for example, a Kurdish national one within an Iraqi civil “nation.”

Given their history in Iraq, this position sees only three acceptable institutional solutions for its aspirations. In order of desirability, the first would be a greater Kurdish state incorporating also the Kurds of Turkey, Iran, and Syria, an option everyone regards as impossible in the short and middle term. The second would be a smaller Kurdish state carved out from Iraq, encompassing both the three governorates plus the fragments of two others in the present Kurdistan region and all Kurd-majority areas or even Kurd-plurality areas in Iraq, including Kirkuk. This option would be undesirable without the added territories and may be currently impossible with such additions, so there is also a third formula, a binational state with a more or less independent Kurdistan within it. This is seen by the ethnic nationalist as a huge concession from the point of view of his or her first and second options, a mere third best, and in return there is a definite expectation of the territorial expansion of the Kurdish part of the binational structure to include all Kurdish majority and even plurality areas, including Kirkuk province and Kirkuk city. As we have seen, in this view of things, such a confederation or federation (not really a state) should be negotiated bilaterally between Kurds and Arabs. Ideally, it would have two symmetric parts, one Kurdish, one Arab. But the organization of each should be up to its own constitution, and in theory it would be acceptable that the Arab part organize itself subfederally, in terms of, say, thirteen to fifteen provinces or governorates. Thus an asymmetric structure on a Canadian model (the Arab part would not have its own regional government, only the federation government; the Kurds would have two governments) would be acceptable, depending on the status of the whole and the powers given to the parts (great) and the whole (very limited).49 As long as each part—that is, first and foremost, Kurdistan—retains a veto over all constitutional legislation, foreign and military policy, and possibly all national decisions of any importance, even a three-part organization (Kurdistan, a Shia region, and a Sunni region) or a five-part one would be acceptable. The stress is on the veto power.

The ethnic nationalist perspective to the extent it accepts Iraq at all sees it as a treaty organization, a confederation, or a federation (not federal state) only somewhat more centralized, if an asymmetric structure is conceded. At the same time, the ethnic nationalist will tend to accept the empirically false and logically somewhat incoherent idea of Brendan O’Leary (himself a liberal nationalist) that there is some kind of deep structural link between three dimensions: ethnically defined federations, powerful units with weak centers, and power sharing in the center.50 And, in fact, the linkage is more logical from the ethnic nationalist point of view than otherwise, though it is not completely clear why someone who wants to separate would still want to rule the unit one is separating from. However, the motivation is fairly understandable. If the ethnic nationalist cannot have his independent state, he will want a three-fold guarantee against the “state” that is conceded to the federation, which will make the unit itself a quasi-state. Note, however, that in this version power sharing means a device to weaken the central federation by a system of rigid vetoes.

Civic Postnationalism or Republican Nationalism (Arab, American)

There is no question that this relatively well represented position in the IGC and the Drafting Committee in terms of individuals lacked a power base and may have appeared extreme and ideological.51 Its advocates accepted Kurdish claims that pan-Arab nationalism has resulted in great oppression of and crimes against the Kurds. But replacing an ethnic national state with a binational state or by ethnically based federalism in their minds would be no solution. When Arabs such as K. Makiya make the argument, they often use an Israeli analogy. In Iraq, like Israel, ethnic definitions of the state or of units of the state would be in the end incompatible with democracy, because those not part of the relevant ethnic group would be lesser citizens of the state or the unit.52 Iraq (and its units) should be a state (and units) of all its (and their) citizens, and they should all receive the same rights and obligations as citizens of Iraq. Federalism is here favored not as a way of instituting special identities but as another set of checks and balances against arbitrary government (“separation of powers” and “protection of minorities”), but federal units organized on an ethnic basis could themselves become small-scale but equally potent threats to individual and minority rights as could an ethnically defined national state.53 Ethnic federalism would lead to the complete ethnicization and, in Iraq, the sectarianization of politics, which would threaten the survival of any kind of statehood. One answer is therefore comprehensive separation and division of powers, where all the different branches and levels—central and decentralized—control, monitor, and correct one another. Another is fiscal federalism (central control and equitable sharing of a large share of the resources to the units) complementing the territorial one that splits up ethnic fiefdoms.54

There are two possible versions of the civic model, a postnationalist and a republican nationalist one. The difference has to do with the thickness of the nonethnic collective identity that is affirmed and its resulting openness (of the postnationalist) or suspicion (by the republican nationalist) toward claims of subethnic nationalisms when restricted to demands for cultural autonomy. It could be said that while the postnationalist could live with a “state nation” concept as proposed by Linz and Stepan, involving multiple identities and multicultural rights, the republican nationalist still imagines a “nation state” but with all requisite individual rights.55 It is very hard to say where Iraqi liberal advocates on the Drafting Committee would have defined themselves in relation to these two positions. Most likely, the republican conception may have seemed a little too close to Arab nationalism (see below) and was not considered to be worth advocating under the circumstances and given the way the IGC was constituted. But it is also possible that all civic nationalists were also committed or strategic multiculturalists, given the atmosphere of our times, especially in the patron country.

However that may have been, although advocates and even states may not be entirely coherent on these matters, a whole variety of federalist arrangements are compatible with the two versions, granting stronger or weaker powers to the units and to the whole, which could be a centralized or a decentralized state with provinces, a federal state, or a federation, but not a confederation or an asymmetric federation with one “federacy” that has a confederal, treaty-based status. Of course the model allows for the possibility, as in India, of a highly (though diminishing over time) centralized federal state, with some or even most of its territorially defined units having an ethnic majority, but the units themselves not being ethnically defined and therefore a consolidation of units on merely ethnic grounds not easily permitted.56 Disincentives to such consolidation57 can be established, or they would need to involve constitutional amendments if not outright bans. Amendment rules would involve participation by federal state organs and legislatures or electorates of the units, according to various possible quantitative proportions, but outright vetoes would not be allowed. The question of whose powers are enumerated and whose would be the reserved powers need not be solved in the American way, for example, and current theorists tend to favor enumerating both sets of powers as well as shared powers. With respect to Iraq, this position in its postnationalist and some republican versions would affirm or allow a federalism based on eighteen provinces, with significant powers devolved to them. Evidently, it would have to accept the fact that each province would have an ethnic majority or plurality. The postnationalist at least could offer cultural autonomy to all the main nationalities of the country, which could go so far as establishing two official and several other protected languages, allow public use of several above a certain threshold of population, establish institutions of higher learning in at least Kurdish and Arabic and other schools in all protected languages, and so on. But the constitution in the postnational version would not define the state as that of one or of two nations, and it may not mention the word nation at all. Or alternately, in a more republican version (coming closer to Iraqi nationalism, see below), it could define the Iraqi nation in terms of all of its citizens, whatever their ethnicity, religion, or gender.

Liberal Nationalism (Kurdish)

The liberal nationalists are clearly different from both the ethnic nationalist and the republican nationalist positions, because they think in terms of the possibility of multiple identities. They would not go so far as to adopt the category of “state nation” for Iraq. Thus liberal nationalists postulate the possibility of two or even more national identities within a single non-national state identity, for example “Iraqi identity.”58 Its advocates say they are liberals but “not difference-blind liberals.” The position even prefers a relatively thin civic definition of nation, but it argues in that case that in Iraq two such nonethnic definitions are needed, one Arab and one Kurd, or possibly three, one Iraqi, one Arab, and one Kurd.59 The argument for this cannot be theoretical, since theoretically either one (Iraqi) or three such identities fulfill the same civic purpose, and indeed the two-part Arab-Kurd division threatens to reethnicize the civic conception. (One could be Iraqi and Arab, Iraqi and Kurd, or just Iraqi, but never Arab and Kurd.) The reason for making their particular choice (aside from latent ethnic nationalist sympathies) is historical: the bitter experience of perhaps the largest “nation” without a state, the Kurds, at the hands of Arab nationalism requires separation if any common state framework is to be preserved. Here the example of Israel is used in quite a different way than it is by Makiya: genocide helped produce a Jewish state, not integration-minded Jews.60 That is a fact, but so are the consequences, good and bad. Makiya’s point regarding some of the outcomes of an ethnic definition of the state in Israel is not thereby diminished, especially to an Arab audience, but apparently that is not to whom the liberal nationalist is speaking.

Admittedly the model, unlike that of the ethnic nationalist, goes beyond the leading Israeli paradigms today. While the Kurds, like the Israelis, simply cannot and will not trust Arabs in any framework that does not make them the center of a distinct statelike formation, that formation can however “federate” on the basis of mutual need and interest with an Arab statelike entity called Iraq (or in the least nationalist version, even “in Iraq”). Thus for the liberal nationalist too the maintenance of the Kurdistan region is not negotiable, and its geographical extension is a highly desirable goal. While important Kurdish politicians such as Mahmoud Othman and Hoshyar Zebari seem to hold fairly consistent versions of this position, it has been developed in the greatest detail by several foreign advisors, who use it to reply to the charges made by the civic nationalists and postnationalists against the ethnic nationalist perspective. However, the distinctness of the position when compared to ethnic nationalism comes into question. Understanding the Kurdish perspective as a civic rather than ethnic nationalist one, O’Leary and Salih defend the position against charges that Kurdish nationalism could be as repressive over a smaller territory as Arab nationalism was over a larger one.61 The historical experience of Kurdistan since 1991 partly bears out their claim, although Kurdish rule in Kirkuk more recently has left a lot to be desired as well.62 But the real question concerns the future rather than the past. Here even the foreign advisors of the Kurds differ, and there is much more willingness on the part of some (such as O’Leary) to see the guarantees for individuals and minorities in a future Kurdistan also in terms of state-and federation-wide relations of checks and balances. Others (Galbraith) push for a kind of confederal status that leaves Kurdistan, when expanded in territory, part of a larger integration in name only.

There are, I think, important strategic differences between Kurdish perspectives, differences that roughly correspond to the ethnic and liberal nationalist positions even if inconsistently. They do in the case of O’Leary, the most consistent thinker on the side of the Kurds. The liberal nationalist also trades Kirkuk only because he must. But, despite the fact that he may accept some kind of link between ethnically based federalism (strong powers for the regions and power sharing), he is willing to see these devices as functionally interchangeable protections for the region and the ethnic group.63 He wants power sharing not only to weaken the federal state but to retain a strong federal state for the purposes deemed legitimate or shared. Thus he should be more willing than the ethnic nationalist to trade some powers of his ethnically defined region, because he wants a somewhat stronger organization than mere treaty-based integration.64 In return for what is given up, the liberal nationalist seeks to have greater powers in the federation, which as a minority the Kurds can get reliably through consociational structures of power sharing and less reliably through a federal chamber either suitably, that is proportionally, or, in their favor, disproportionally organized (but not according to a system of eighteen governorates of which the Kurds have three, or one-sixth, as opposed to their one-fifth share of the population). In order to constrain his own ethnos, the liberal nationalist can even affirm a strong constitutional judiciary with a strong Kurdish presence.65 Here the problem is only that enforcement mechanisms in other federal states or federations involve strong executives, federal interventions, federal police forces, strong federal military, and the like—the very institutions the liberal nationalist opposes creating, along with his ethnic nationalist colleague. Finally, logically, seeking a stronger integration than a treaty organization would suggest an amendment rule perhaps between those of the civic postnationalist and the ethnic nationalists’ veto, but here too the actual positions of liberal nationalists and the ethnic nationalists on the Kurdish side tend to become indistinguishable.

Other Positions (Arab and Iraqi Nationalists)

Ethnic nationalism has obviously existed among Arabs too, as pan-Arabism or Arab nationalism, and it has always interpreted and fought for Iraq as a Sunni Arab country that should grant cultural rights to Kurds and Shi’ite Arabs very reluctantly and sparingly—and territorial rights not at all. The perspective is thus constitutionally strongly centralistic, in line with Iraqi traditions (at times compromised vis-à-vis the Kurds). It was entirely excluded from the negotiating process, despite its continuing political popularity in Iraq among Sunnis. What is obvious is that even if the perspective had been present its chances of winning would have been nil. Its exclusion nonetheless had some consequences. Paradoxically, had Arab nationalists been present, it would have been easier to see the postnationalist position as a possible basis of compromise. Otherwise the IGC would have had to face the internal prospect of a polarization on the lines of ethnic nationalisms, followed by the inevitable breakup of the country itself, which at the time most of the members would not have relished. The best way to avoid this would have been to eliminate the question of national definition from the discussion altogether. At the very least, the postnational or a compatible Iraqi national position could have been strengthened. Thus the exclusion of an undesirable perspective both weakened its role and shifted the whole intellectual balance of the discussions. Still, centralism had its advocates among the Shi’ite clergy, the potential beneficiaries. This, however, was a very weak position because among the exiles and their American sponsors “federalism” was always accepted as a magic mantra that could not be compromised. Moreover, the Shi’ites too have suffered because of Arab nationalism, from which they were excluded as “Persians” or because they follow a supposedly non-Arab version of Islam. The form of nationalism that has periodically appealed at least to more secular Shi’ites (and many Kurds, during the Bar Sidqi experiment, with the Communists, and under Kassem) was “Iraqi” nationalism, which was a nonliberal version of the civic republican form; according to this, Iraq was an Islamic nation of all its ethnic and religious groups.66 Perhaps understanding their relatively narrow majority, they were not interested in explicitly redefining Iraq as a Shi’ite Arab nation. But they were nevertheless allergic to liberal postnationalist or even civic republican definitions of the political community, which to them in any version reeked of secularist, antireligious biases and traditions well known in the region.67 In any case, they were both too distracted and divided to strongly represent Iraqi nationalism against the Kurdish gambit in either its ethnic or liberal version. As I will show, identity issues for them came to be focused on the role of Islam in the state, which was rather irrelevant constitutionally because here local control rather than constitutional formulae was going to decide things. But they did not seem to care too much whether Iraq was Arab or Arab and Kurd or just Iraqi as long as it was Islamic. Second, the more politically savvy among them early on saw the differences among alternative federal proposals that were functionally equivalent to the Kurds, namely whether the “rest of Iraq” would be one or two or four regions in a symmetric structure or merely fifteen provinces in an overall asymmetric one. And depending on party and geographic constituency, they either opposed regions altogether or supported them because they too wanted one or two of them in oil-rich areas with large Shi’ite majority populations. Until the final round of negotiations, their own choices or their divisions excluded them from this part of the discussion, and the basic agreement concerning the Iraqi state was thus made without them. When it was crowned with a ratification rule that protected the new arrangements, they woke up much too late.

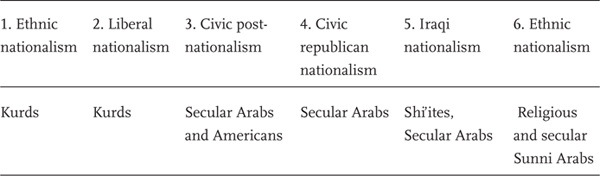

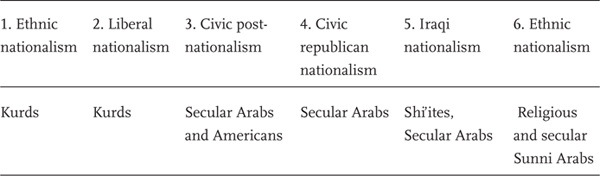

TABLE 2

Varieties of identity positions on Iraq

Purely intellectually, the weakness of positions 4, 5, and 6 in the process (and especially the absence of 6, which would have been the most aggressive) tended to make Kurdish liberal nationalism rather than postnationalism the natural basis of compromise. Moreover, because of their harsh disagreement over Islam, secular nationalists and postnationalists and Shi’ite Iraqi nationalists had trouble finding common ground; in fact, each side seemed to be more comfortable with the Kurds, who were flexible on the big symbolic issues. They were Islamic but not fundamentalists. “Socially” (and such issues influenced even the highly sophisticated UN delegation), that put them between the liberals and the “Black Turbans,” who did not as a result see that as far as the main issue was concerned they were together on the opposite side of the Kurds. Aside from the structure of bargaining, the intellectual positions of the Kurds, especially the ones who did not argue on the grounds of ethnic nationalism, could begin to occupy a middle ground. Two things should be noted. Organizationally, as I already explained, there were two fundamental choices (rather than three): (1) a bargaining situation involving two parties, Iraq and the Kurds (a two-sided table), or (2) one in which the Kurds would be one actor among several (round table). On this point the two Kurdish positions were in agreement, and in fact both adopted the ethnic nationalist premise of “Iraq as a voluntary union.” Even more importantly, they managed to have their way. Just as the American negotiators, who originally started out with simple but reasonable versions of the postnationalist federal conception (eighteen-province, genuine federalism with full cultural autonomy), were brought into the Kurdish framework by accepting the negotiating model, the same process also blended the two Kurdish perspectives even closer together. To an extent, the ethnic nationalist position became the long-range objective if not the bottom line, and the liberal nationalist governmental schemes and statements of values became either public-relations tools or strategic bargaining ploys. Even if this is a slight exaggeration, the weakness of the opposing perspective pushed the supposedly compromise position, the Kurdish liberal nationalist one, in a more ethnic direction. Here are my hypotheses concerning the intellectual causal scheme that, in itself of course, could not have been decisive: the American exclusion of the Sunni nationalists led to a Kurdish center in the spectrum of positions. The weakness of the Shi’ite Iraqi nationalists and the secular postnationalists, who could not form a real alliance, made the other extreme, the Kurdish nationalists, stronger, and this made the center, the Kurdish liberals, move toward their positions.

Political outcomes, however, do not take place first and foremost on the level of ideas. Undoubtedly, the surprisingly weak pressure of the Americans on behalf of a civic postnationalist perspective they were expected to favor was to be an even more fundamental reason for what was to happen, and it is to this dynamic that I will now turn.

The State Bargain II: The Process

The Creation of the First Drafts

Looking at all the negotiating venues and their products, it becomes clearer how in the end a Kurdish amalgam of ethnic and liberal nationalist elements triumphed. I will here focus only on questions of state structure and political identity. In the Drafting Committee led by Adnan Pachachi, the civic nationalists and postnationalists were apparently strong, mainly because of the role of the chairman. Whatever Pachachi himself represented during his first governmental role (before 1968), he was now an Iraqi (rather than Arab) secular nationalist68 opposed to ethnic federalism, provincial control of oil resources, and forms of power sharing based on ethnicity.69 He worked mostly through Feisal Istrabadi, who held similar views and who as a drafter and advocate seemed to have been quite accomplished and impressive.70 I do not know if at this level persuasive arguments of the type we see in Makiya’s well-known piece were attempted on behalf of civic postnationalism or Iraqi nationalism. Given the strong convictions of the chair and his top representative on this ten-person committee, there were certainly some frank exchanges of views. Whether or not there was any serious attempt to persuade, strong threats were certainly used on both sides, using external instances to pressure the drafters.

In December, according to Diamond, “Washington” informed the Kurds that they would have to give up their region and their regional government and would have to accept a federalism based on eighteen provinces. This was certainly based on a common opposition in the Pentagon, State Department, and White House to ethnic federalism, which they saw as a formula for the unacceptable breakup of Iraq.71 This converges with both O’Leary’s view that the U.S. authorities interpreted the November 15 Agreement in the sense of territorial or eighteen-province federalism (though this is not really supported by the agreement’s rather vague wording) and with evidence that the Kurdish signer J. Talabani came under strong pressure in Kurdistan for even signing the document.72 In reality, the agreement was vague on the question of federalism and did not exclude a Kurdish region or a special status for the Kurds.73 In any case, the Kurds responded with very strong threats of their own, including secession.74 On December 20, 2003, the five Kurdish leaders on the IGC submitted a draft “bill” in which they outlined their vision of federalism.75 In Barzani’s summary, directed against both Iraqi and “foreign” interlocutors, the main principles were the voluntary union of two peoples (Iraqi and Arab used interchangeably for the other side), no surrender of anything in the existing situation including the Kurdistan Regional Government, the rejection of the separation of the Kurdish governorates from one another and at least to this extent province-based federalism, and the inclusion of all other “Kurdish areas” in Kurdistan, including Kirkuk.76 Finally, the Kurdish members of the Drafting Committee (among them Fersat Ahmad) submitted a list of specific demands, based on “draft constitutions” adopted by the Kurdistan National Assembly in October 2002, for inclusion in the TAL. Among them:

the establishment of a federal Kurdish region, recognition of Kurds as one of the two main nationalities of Iraq, recognition of Kurdish as an official national language alongside Arabic, recognition of the Kurdish (regional) flag and anthem, reversal of Arabization in mixed areas and a highly evolved form of decentralization that would give Kurds a significant degree of autonomy and control over resources in their federal region. Proposed language concerning non-Kurdish matters proved relatively noncontroversial but everything having to do with Kurdish aspirations led to stalemate in the committee, which operated by consensus.77

At this point, the different venues interact. All sources indicate that Bremer went to Erbil to break the deadlock in the Drafting Committee.78 But he did not really get any results until later in the month (January 7, at the earliest, but that was only an outline conceding the existence of a Kurdistan Region), since the deadlock at first continued in Erbil, as we will see. Meanwhile, obviously not unaffected by the American-Kurdish negotiations, and with some possible help from the Governance Team, which was focused on other issues given Bremer’s instructions to remain hands-off, it is nevertheless possible to argue that the Drafting Committee produced a compromise (or at least “amalgamation,” according to the Crisis Group)79 of its own, based on its earliest draft (which we do not have) and Kurdish submissions. According to Diamond,80 during the first days of January there was already a draft he could read, written by an unnamed advisor of Pachachi and translated as well as redrafted by Istrabadi. This text has never been published, but from Diamond’s critical description we can tell that it strongly resembled what has been called the Pachachi draft, which was published in Arabic on February 1.81 It did not seem to contain a formula on federalism, however—at least Diamond does not mention such a thing. This can be taken in terms of the emerging formula for all of the early versions: leave the status quo as it is for the transition period and let or even require the elected constituent assembly decide most but not all the issues linked to the ultimate meaning of federalism in Iraq. The one issue I think the drafts did decide (possibly and even likely because of Bremer’s deal on January 7) was that there would be a territory called Kurdistan beyond provincial federalism if that was the scheme ultimately chosen. And this was a concession to the Kurds, even if it fell well short of the idea of a voluntary union. I will rely on the one published version to make the argument and will use O’Leary’s commentary as a partial corrective.

The Pachachi Draft seems amateurish next to the finished TAL, but that is in retrospect a very misleading impression. It has been rightly said to be “deliberately short on detail” and this, I think, was a matter of both democratic and international legal principle. Given the legitimacy problems of the CPA and the IGC, due to Sistani’s demands for a freely elected assembly, the idea of significantly binding a body with much higher legitimacy than the drafters of the TAL may and should have seemed unacceptable. Given international law, the idea of seriously transforming Iraq’s state structure and indeed irreversibly altering its regime under and by the authority of a foreign occupation also could and should have seemed unacceptable. But it was exactly the latter that was sought by the Kurds, who rightly recognized that a detailed interim constitution would help create or legitimate facts on the ground that would be very difficult to reverse later in a permanent constitution. Thus all the Kurdish proposals were highly detailed in all matters that concerned them.82 This invited “compromise” solutions that would be themselves highly detailed, as the TAL eventually was, and therefore this structural issue of the type of interim constitution represented not a compromise but the adoption of the Kurdish preference of neutralizing the constituent assembly reluctantly conceded to Sistani, one elected on the basis of a one-person-one-vote principle.

According to the Pachachi Draft published on February 1, 2004, Iraq is an independent and sovereign state with a democratic, parliamentary, pluralist, and federal “system,” but it is neither said to be Arab, or Arab and Kurd, or multinational, or any other kind of “national” (art. 3). In line with a postnationalist conception, or because no decision was possible, “nation” is not mentioned in the draft. Language is, and it is, in line with a more republican model, Arabic (art. 3). Regarding both these provisions, it is said that in the transitional period the current special status (regarding statehood) of Kurdistan and current special situation (regarding language) in the territory of Kurdistan shall be respected. The name Kirkuk is not mentioned in the draft, but respect for current special status would not in any way include Kirkuk city and Kirkuk province in Kurdistan, which after being captured by the Kurds from Saddam’s forces have been, unlike Kurdistan, occupied by the Americans—at least formally. Thus the draft does not meet any Kurdish demands regarding Kirkuk nor does it promise that the constituent assembly would even deal with this question. For the transition period, federalism is discussed only indirectly, with references to the eighteen provinces (one of which is Kirkuk) and the applicability of the TAL itself in all of them, and by outlining the powers of central government: foreign policy; defense; guarding of borders; peace and war; monetary, currency, and development policy; public budget; and citizenship affairs (art. 3). However, as this draft contains some ironclad principles for the drafting of the permanent constitution, one of these is relevant to federalism: the final constitution must include “a democratic, pluralist federal system including a unified Iraq and organizing the relationship between the territory of Kurdistan and the central government.” While this language again does not include Kirkuk, in one respect at least this version of the TAL would seem to preempt the elected constituent assembly: there would have to be in whatever federal formula chosen a place for a territory called Kurdistan, and not just three or four Kurdish majority provinces or governorates (art. 42). However, it is not clear who would control adherence to the constitutional principles, and whatever formula emerged in the final constitution would have to be approved in a referendum that without further elaboration seems to be a countrywide vote requiring only majority approval.

O’Leary is working with either a later version, a different translation, or a somewhat arbitrary interpretation of the Pachachi Draft.83 That is why, surprisingly, he detects a harder-line position on the Arab side than I have. Either his polemical reading style, the translation, or the then current state of American-Kurdish negotiations could be responsible. There are crucial differences between our readings. The control of integrated armed forces and natural resources seem to be new, and could have been included at the behest of Bremer, to counter relevant Kurdish demands. The declaration of the Kurdistan Regional Government as a “subordinate level of government” seems to be new, but instead of a denigration, this seems to have been rather an acceptance of the Kurdish demand that the KRG would not be abolished. I note that the supremacy of the Federal State is not as O’Leary thinks “a wholly antifederal” but only a “wholly anticonfederal” mode of thought. There has been such supremacy in the United States, (West) Germany, India, arguably the European Union, and even Canada, though not recognized by those in Quebec who seek a confederal status. Other features of the two drafts regarding federalism seem to be the same, though interestingly O’Leary does not mention what would have been for him strongly in the “minus” column, Arabic as the official language, and, on the “plus” side, the limitation of the constitutional assembly by a constitutional principle that seems to enshrine the territorial integrity of Kurdistan. Perhaps these elements were now gone. There was a trend among the drafters of the TAL, because of the legitimation problems of the whole process, to eliminate constitutional principles binding the constitutional assembly in the South African manner. The powers of the constituent assembly were, however, still there, and O’Leary explicitly mentions the (implicitly or explicitly?) majoritarian ratification rule for the final constitution.

The CPA-Kurdistan Regional Government Bargain

I think it would be a great mistake to see the early drafts emerging from the IGC Drafting Committee as the basis for the eventual compromise with Kurd positions. Of course, one can put various proposals next to each other, extrapolate some such relationship, and argue that the TAL created something like the Pachachi model in Iraq and somewhat modified versions of Kurd proposals for Kurdistan.84 This very dualism, however, was itself the heart of the Kurdish proposal and therefore should not be understood as some kind of compromise. Whatever real bargaining occurred after the Drafting Committee deadlocked was between Bremer and the Kurds, and thus if anyone compromised it was them, around their own positions, which in the case of the CPA were constantly shifting. Initially at this venue too there was deadlock. But the point of this negotiation from the very beginning was that neither side wanted to act on or even fully articulate its most potent threats (which would have been fundamentally unequal), and as a result there was genuine give and take. After the January 2 “acrimonious and unproductive session,” when each side presented its hard-line position, Bremer returned in seventy-two hours with Ron Black-will, and the two sides made an effort to avoid taking inflexible positions.85 Bremer seemed to understand the history that had led to the special position of the Kurds, appreciated their military alliance, and supported their demand for federalism, but only within a unified Iraq. Moreover, he rejected settling the most difficult questions (for example, Kirkuk) in an interim document, and said the United States would not accept a federalism based on ethnicity, which he very rightly recognized as “a central feature of the Kurd’s draft.”86 Thus the Kurds gained very little at this point. But Bremer realized at the same time (“Barzani remained silent”) that they were not going to simply give in to the American positions. He “left Irbil with a sense of apprehension.”87 According to Diamond, before they left, they decided to defer the question of ethnic versus provincial federalism and concentrated on the powers of government. The idea was that if the Kurds agreed to a strong central government with sufficient protections, maybe they could have their ethnic federalism after all. I think in the end the opposite happened, but the strategy made a great deal of sense. With the most important issues left undecided, the Kurds were willing to entertain the possibility of a relatively strong central government with exclusive control over defense, oil and water resources, fiscal and monetary policy, and borders.88

By January 7, the Kurds got Bremer to return to the theme he was avoiding. In return for conceding a relatively strong central government, they wanted him to accept that they could not retreat to where they were before the war in 2003, and therefore accept the principle of a “voluntary union with Iraq.” This time what was always their truly fundamental principle was not completely rejected.89 They also got Bremer to accept some modest action on Kirkuk and the establishment of a property-claims commission to adjudicate longstanding disputes due to the policies of Arabization. At the same time, the leaders of the CPA heard but did not (yet) give in on other Kurd demands, notably the nullification of federal laws, the retention of the Peshmerga, the banning of federal troops from Kurdistan, and a binational definition of the state. Nevertheless, in Diamond’s not implausible view at these January meetings, which continued through the month sometimes with and sometimes without Bremer, a “historic bargain” was struck between the CPA and the Kurds, based on the tradeoff of significant central powers and the preservation of a unified Kurdistan region with far greater powers than the eighteen provinces (or rather fifteen, because the three in Kurdistan would have no powers). Advocates of the Kurds do not see matters this way. According to Galbraith, on January 27, 2004, Barzani and Talabani met alone with Bremer, a disastrous mistake on the part of the Kurds, as he earlier explained.90 At that meeting, the three seemed to have agreed to a formula that sounds like Diamond’s “historic bargain”: Kurdistan as a federal unit and a central government with great powers, including military and judiciary powers. The Americans thought they had an agreement, but according to Galbraith the Kurds later claimed they did not. It is difficult to know whom to believe. Given the power difference, one would have to go with the Americans, ordinarily, because they could insist on the deal being honored. But these were not ordinary times, and the United States did not have an ordinary government during them. In any case, even Galbraith says “fortunately” it was the Americans themselves who abandoned the deal.

At this point, the accounts of Diamond and Galbraith merge. According to Galbraith, it was on February 6 that Bremer informed Barzani that all references to the Kurdistan Regional Government would have to be struck from the TAL at the insistence of the White House, along with Kurdish as a second official language.91 While this set of events is interestingly missing from Bremer’s otherwise pretty complete memoirs, they are confirmed from the other side by Diamond. Chandrasekaran specifically mentions Rice and Wolfowitz as both being behind the order to Bremer.92 The Kurds, feeling double crossed (a different story than Galbraith’s, because this would indicate initial adherence to the January 27 agreement), retreated to an extreme and even more truculent position. Now even moderate leaders, including the remarkable Mahmoud Othman, joined the chorus of more extreme demands.93

The so-called Kurdistan Chapter, submitted for inclusion in the TAL on February 13 but first discussed on February 10, 2004, was clearly a unified Kurdish response to the new American position. It was neither an initial bargaining position nor primarily a response to a Pachachi Draft, as O’Leary and the Crisis Group claim.94 Galbraith, who along with O’Leary seems to have been one of the authors of the Kurdistan Chapter, makes a much more convincing case for the chronology and the politics of this proposal, though it is surprising that these sophisticated operatives, working so closely together, have not gotten their story straight.95 For the moment, I wish to only summarize this proposal and consider its details in comparison with the final TAL arrangements themselves.96 Only a few matters would be the province of the federal government; otherwise Kurdistan’s laws would be supreme in the region. Kurdistan would have its own army and own its oil resources, but it would not manage fields currently in operation. Iraqi troops could enter Kurdistan and taxes could be collected there only with the permission of the Kurdistan national assembly. The permanent constitution would apply in Kurdistan only if approved by a majority of its voters.97

We have only Galbraith’s testimony for what happened at the next negotiating session, with Bremer back in Erbil. That he supposedly insisted on the January 27 agreement is hard to believe, since the White House repudiated it. But anything is possible; perhaps he already got his bosses to backtrack, since they in reality only had the option either to come up with a credible set of threats or make concessions. He refused to discuss the “Kurdistan Chapter.” Then or at a subsequent session, he got the Kurds to give up recognition of the Peshmerga and agree to its formal dissolution (which the Kurds would certainly not go through with) and to federal control of resources in the TAL.98 Meanwhile, having persuaded Washington of the necessity of preserving the Kurdistan Regional Government, this key institution was again conceded to the Kurds, along with Kurdish as an official language and some partial measures for reversing the Arabization of Kirkuk before the final settlement of this question.99 Note that a key result was, despite many strong words by Bremer to the contrary, an asymmetrical form of federalism that established the most powerful unit on entirely ethnic grounds. The other parts of Iraq would be under the system of provinces; only Kurds would possess a powerful regional government to protect their interests. All others would only have one government, the federal one, and how strong that would be was again made dependent on the Kurds. Somewhere along the line—I cannot tell when—a new balance sheet was drawn (most likely by the American experts of the CPA, or the experts of the KRG, or somehow the two together) among the powers of the federal state and that of the region, and, amazingly, the right of nullifying (amending, not applying) federal laws in all but a few enumerated areas was conceded to the Kurds as well. It is because of this structure that people began to speak about a “historic bargain” or a “historic compromise.” To me it looks rather like a compromise well tilted in the direction of the Kurds, but that outcome, already prefigured in the bilateral structure of the negotiations, would not be fully visible until somewhat later, when the Kurdish-CPA bargain was processed through the body officially responsible for enacting the TAL, the full IGC.

Imposing and Negotiating at the Interim Governing Council

Consider the position of the IGC. Its own Drafting Committee, having recommended the bare outlines of a provincial federalism but conceding some undetermined special status for Kurdistan as a constitutional principle, left the actual work of producing a model (in accordance with both democracy and international law) to a freely elected constituent assembly that would be no longer under foreign occupation. Now they were suddenly given a “compromise” model of asymmetrical provincial-ethnic federalism hammered out in a state bargain by the Kurds and Americans. Did they have the power to resist this deal, especially when the strongest opponents of ethnic nationalism, the secular postnationalists, were weak on the council, and when the Iraqi nationalists among the Shi’ites were distracted by religious issues? One response, the line of least resistance, was that the Drafting Committee and especially the American Governance Team proceeded apace to fashion a TAL consistent with the basic idea behind the bargain. Indeed, as I will show, under the false assumption propagated by the Kurds that it was they who had surrendered the most because of the signature issues of “Kirkuk” and “oil,” a governmental structure was negotiated that would have made sense only if the powers of the federal units were much weaker, in line with the very early strategy of the CPA.100

But then three new things happened. The Kurds decided to insist on the “Kurdistan Chapter” as a formal submission to the TAL, despite the fact that they did not get Bremer’s assent to this. Some of the Shi’ites became attracted to a symmetric model of purely ethnic federalism. And third, everyone became sidetracked by the mainly, but not exclusively, symbolic issue of the relationship of Islam to the state.

The Kurdish challenge came first, inviting the Shi’ite move on federalism as a response. What was originally a response to Bremer’s repudiation of a prior agreement now became a stake in Kurd-Arab negotiations, renewing the possibility of deadlock. And this released the Arab, mainly Sunni and secular members of the IGC, who now roundly attacked ethnic federalism and the danger of dividing Iraq.101 This time, however, a deadlock did not occur, for two reasons. One is that Bremer, though he did not formally accept the Kurdish laundry list not previously agreed to, given his bargain with the Kurds, also did not renew his own earlier strong stand against ethnic federalism in any way; thus in effect he switched sides. And a new and unpredicted division occurred on the Arab and even the Shi’a side: some of the Shi’ites, mainly around SCIRI, became interested (or revealed their interest) in an entirely ethnic-based, symmetric form of federalism where they could “have everything the Kurds have.”102 While the Kurdish idea of a voluntary union made most sense with a two-member Kurd-Arab treaty organization or confederation, it could be made compatible with an asymmetric structure negotiated with Bremer as well as three-member or five-member “federations” or “confederations,”103 always with the proviso that the Kurds would retain a veto over all constitutional changes (preferably for all Iraq but at least as they concerned Kurdistan).

Once it became clear that only Kurds were getting a potentially strong regional government to protect their interests, in a setting where the federal government might be weak, the disadvantages of an asymmetrical structure for the Arabs became clear. This was especially true for some of the religious Shi’ites, who had a primarily southern base and who, like the Kurds, could hope to control large oil resources in their territory, whatever early arrangements for resources were to say on the matter. One could have assumed that the religious Shi’ites had the greatest interest in a strong majoritarian central government, because they could control it. This was so if they were united, but they were not. Regions with oil had different interests than regions without it, and the attitude to Iraqi nationalism was also different between the various parties (the SCIRI, Da’wa, and, outside the IGC, the Sadrists, to whom one did not want to lose the oil-poor urban vote). Moreover, now the Americans were helping to remove Kurdistan from central authority, and the negotiating process began to favor power sharing, as I will show, and thus a weak government no one would exclusively control. Thus having what the Kurds had made a lot more material sense, especially for those for whom symbolic issues of identity were increasingly articulated on a transnational rather than national level, concerned with Islam rather than nation. It may even be that this turn from Iraqi nationalism made their demands on behalf of Islam, the other possible center of identity, all the more vociferous. But more likely it was the other way around. Interest in the transnational allowed them to focus more on the homogeneous region than the heterogeneous state.