Tamo has many names. The one name we don’t know is the name his parents gave him when he was born in India more than fifteen hundred years ago. In China, though, he is called Tamo, in India Bodhidharma, in Japan Taishi Daruma. He introduced Zen to China, and he developed the exercises that later became chuan fa, the ancestor of many of today’s Asian martial arts styles.

Tamo, the one they call the White Buddha, once walked all the way from India to China to visit the Chinese emperor and the Buddhist temples there. With him he brought a new way of living called Zen. Eventually, Zen would reach every corner of China and then find its way to Japan. But when Tamo first arrived in China, Zen simply made him an outcast.

It seems that when Tamo arrived at the royal palace, the emperor bragged to him about the monasteries he had built, about the scrolls his monks had translated from Sanskrit to Chinese, and about the way he was bringing Buddhism to the people. Tamo, never one to mince words, told the emperor that all these good efforts would not earn him Nirvana. He tried to tell the emperor about Zen. But the emperor branded Tamo a troublemaker and kicked him out of his palace.

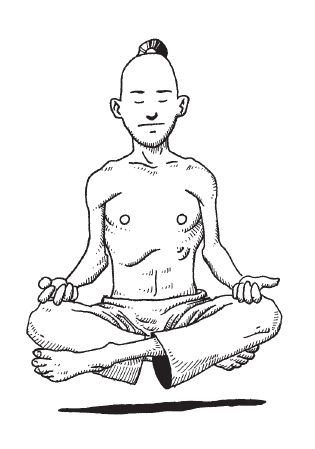

Tamo traveled for a while, then arrived at the gate of a monastery. The abbot of the monastery had already been warned by imperial messengers that Tamo might show up. So when Tamo knocked at the gate, the abbot turned him away. Tamo was not upset. He simply climbed the hill outside the monastery and sat down in a cave to meditate.

In the morning, when the light was right, the monks could see him there from the window of their scriptorium, the place where they translated and copied Sanskrit scrolls. Never moving, he sat, his eyes focused on a single place on the cave wall.

Eventually, the abbot sent a young monk to the cave with food. When he returned, the monk said that he could feel the force from Tamo’s eyes as it bounced off the cave walls. In fact, the monk reported, if you looked carefully, you could see where Tamo’s gaze had

worn small holes in the cave wall. The young monk’s words spread like a fire through the monastery. The next day, the abbot sent an older monk with the food instead. When he returned, the monks asked him if what the young monk said was true. He only replied that he would not engage in idle gossip.

Tamo remained in the cave for a long time. Every day the monks saw him in the same place, the same position, staring at the wall. Respect for him grew. So did the rumors. Finally, the abbot decided that Tamo should come down and talk to the monks. Maybe the abbot respected Tamo’s abilities. Maybe he just wanted his gossiping monks to see that this man was merely human, like they were. Whatever his reasons, the abbot brought Tamo into the compound, and from that day nothing was ever the same.

Tamo showed the monks how to meditate, how to sit quietly on the floor, hands in their laps, eyes fixed on a single point. He taught them how to watch their breath going in and out, how to clear their minds, and take in the energy from the world around them. The monks tried. They tried very hard. A few could meditate from the time the sun first appeared over the horizon to the time it was straight overhead. Most drifted off to sleep after a hundred or two hundred breaths. For all of them, sitting for hours was painful and very frustrating.

One day the abbot and Tamo were walking together through the monastery grounds, talking about the trouble the monks were having with their meditation. They walked through the scriptorium, where dozens of monks sat bent over desks translating and copying. A few napped at their desks. One monk put a hand to his neck and grimaced, rubbing it and moving it back and forth. His neck seemed to have a permanent bend in it.

“Are all your monks in such poor shape?” Tamo asked the abbot. “Well,” said the abbot, “mostly they just sit and translate. It is hard on the body, but it is a worthwhile way to spend one’s life.”

“Yes, no doubt, no doubt,” Tamo replied. “But if I could find a way for your monks to meditate better and do their work better, would you be interested?”

“Certainly,” said the abbot, “What do you have in mind?”

“I’ll let you know when I have all the details worked out,” Tamo replied.

The next day out the scriptorium window, the monks saw Tamo on the hill again. This time, however, he was moving around outside the mouth of his cave. The movements were strange, like dance, but not like dance.

“He looks like a snake,” said one of the monks.

“Perhaps he has been possessed by the spirit of a snake,” said another. “That’s silly,” said a third, a tall monk who was able to see over the top of the others. “I can see it better than you can. It’s just a dance, a snake dance maybe.”

“It doesn’t look like a dance to me,” said the first. “It doesn’t have the rhythm of a dance.”

“Sure it does,” said the tall monk. “It’s you who have no rhythm.” The only thing the monks could agree on was that Tamo’s movement seemed full of life. Something about it—the grace, the energy, maybe the power—drew them in and made them want to be able to do the same thing themselves.

A few months later, the abbot called the monks together. Tamo had something he wanted to present.

“It’s called ‘The Eighteen Hands of the Lohan,’” he said. “Another name is ‘Those Who Subdue or Attain Victory over Foes.’ I learned something like it in my youth. My father wanted me to be a soldier, and so I trained in the weaponless combat arts in India.”

“Wait,” said the abbot. “You didn’t say anything about training my monks to be soldiers.”

“I have no intention of making them into soldiers,” Tamo replied. “It would be a shame to waste such fine translators and scholars on war, just as it would be a waste of good soldiers to put them behind a desk.” He smiled at the monks, who smiled warily back at him. “The enemy in this case is weakness and sickness. A weak and sick translator cannot do his job. A weak and sick monk cannot stay awake to meditate. To fight weakness, we must grow the chi within you. Let me show you.”

Tamo stepped out to an open space in the midst of the group. His face grew quiet. Slowly he began to move. His legs became snakes. Then his fingers made a bird’s beak. His hands struck the air fast and hard like the paws of a leopard, then whipped through the air like the wings of a dragon. Right there, in the courtyard of the monastery, Tamo was transformed into animal energy.

“Do you ever see the animals fall asleep during their work?” Tamo asked. “Have you ever seen a snake coil to strike its prey and then suddenly drift off into a nap?” The monks chuckled. It is because the animals know how to gather, store, and use chi, the energy of the universe. Once you learn the same thing, you too will move with the power of the tiger. You will be able to remain alert while standing motionless like the crane. Come,” he said, “Let me show you.”

That was hundreds of years ago. Several years after Tamo left the monastery, he traveled all the way to Japan teaching Zen and the Eighteen Hands. His students taught other students, and they in turn taught other students. Soon people all over East Asia were doing the Eighteen Hands. Today, more than fifteen hundred years later, people all over the world still practice martial arts that can be traced back to Tamo.