Gichin Funakoshi is best known as the man who brought Okinawan karate to Japan. The style he founded there has become known as Shotokan karate. Funakoshi was a small man, but physically strong from his karate training and mentally strong from his studies. It is because of those strengths and his remarkable selfcontrol that he was chosen over men much more powerful than he was to bring karate to Japan.

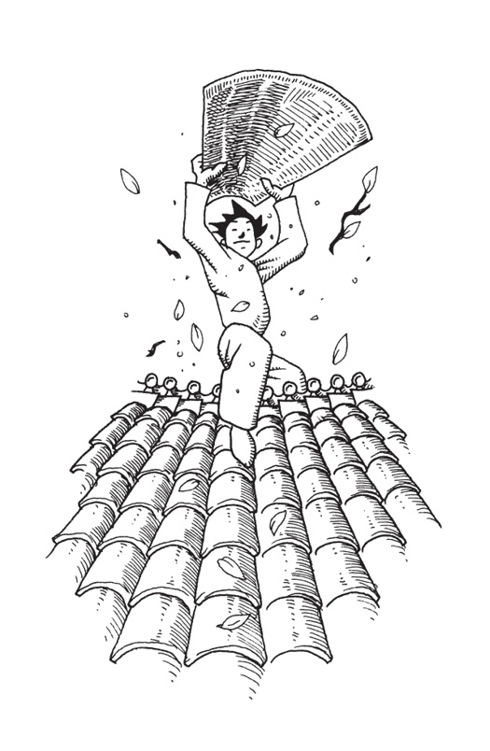

Funakoshi wrestled with the tatami mat he was carrying. The long, narrow straw mat was several inches taller than he was and awkward to carry. When the storm blew against it, the mat bent like a bow. When the wind let up a little or changed direction, the mat sprang straight again, throwing Funakoshi off balance. It was going to be tricky getting the mat onto the roof. Especially tricky given that the rain seemed to be picking up, too.

“Funakoshi-san,” a neighbor shouted over the howl of the wind. “What are you doing? Are you having trouble with your roof? Is it leaking? Maybe you should just let it leak. It’s not safe to be up patching your roof with a typhoon blowing in.”

“The roof is fine, Hanasato-san. Thank you for asking,” Funakoshi called back. He laid the tatami flat against the tile of the roof and scrambled the rest of the way up.

“If the roof is fine, what are you doing up there in your underwear?” Hanasato shouted.

“Just a little exercise,” Funakoshi grinned at his neighbor who was squinting over the side fence, trying to keep the blowing rain out of his eyes.

“Is it one of those martial arts things?” Hanasato asked. “I suppose it is,” Funakoshi said.

Hanasato shook his head. “Does your wife know you’re up there?” he called.

“Oh, yes,” Funakoshi answered. “She’s inside, though.”

“Most sane people are,” Hanasato replied. “Do be careful.” He pulled his jacket more closely around him and trotted back to his house.

Funakoshi climbed to the peak of the house. From there he could see that the sky had turned a sickly shade of gray-green. A branch blew off a nearby tree and struck him in the chest. He looked down. No blood but a large red mark. The wind blew hard against his face, making it difficult for him to catch his breath.

Stability, he told himself, is partly a matter of body, but partly a matter of mind. If a man thinks he will fall over, he will. Slowly, carefully, Funakoshi bent over and picked up the tatami. The wind tugged at it, trying to rip it from his grasp, but Funakoshi held tight, bringing it up edge on to the wind. He took a solid horse straddle stance and turned the tatami flat to the wind.

The wind caught the tatami and lifted Funakoshi up off the roof. His feet scrambled against the wet tiles, trying to find footing, but the wind was in control. A powerful gust grabbed him and threw him off the end of the roof. He landed in the mud, the tatami on top of him.

“Are you all right?” his wife called from the door.

“I’m fine,” Funakoshi answered, standing. “I just need to take a stronger stance before I tip up the tatami.”

“Come inside,” his wife shouted.

“In a minute,” Funakoshi replied. “I know what I’m doing.”

The door to the house closed, and Funakoshi tucked the tatami under his arm and started up the ladder. It was a matter of using the strength of the stance, he thought to himself. He needed to stand sideways to the wind.

Funakoshi squinted against the wet sand, branches, and other debris that beat against him. The wind was picking up. He would have to go inside soon. He took a low stance on the peak of the roof, spread his feet wide apart, tightened his leg muscles, pictured himself gripping the roof with the center of his body. When the straddle stance was the best he could make it, he flipped the tatami up. The wind hit it hard. Funakoshi stutter-stepped back, then caught his balance again. The force blew the tatami hard against his shoulder. The top of it flapped stiffly against his face. Slowly, his muscles straining, he pushed the mat away from him, then let the wind push it back. Again he pushed it away from him, tightening his legs against the force, forcing his arms to hold against the raw power of the wind and rain.

Gradually, still holding against the wind, he shifted his stance—front, back, straddle stance again. His body strained. He fought to keep his mind focused. Slowly, he lowered the mat to the roof. It was a mess, covered with mud, bent and broken in places. Funakoshi smiled to himself. He wondered if he looked that bad. Carefully he climbed down off the roof and entered the house, dripping and cold.

His wife met him at the door with a towel. He wiped off the mud and debris before stepping up onto the tatami floor of the living room.

“Was it worth it?” his wife asked, an amused look in her eye. “Oh, yes,” he replied. “Most definitely.”

Funakoshi dropped his books and shoes inside the front door of his house. On the way to the closet, he stripped off his uniform. Hanging it carefully in the closet, he put on his good kimono and checked his hair in the mirror. The school where he taught was out for the day. His wife and children were already at her parents’ house, and he wanted to get there in time for dinner. Quickly he snatched up a couple of small cakes to offer at the family altar when he got there. It was a two-mile walk, and he didn’t have time to waste.

After a day in the classroom, he enjoyed the late afternoon air. The road to his in-laws’ village took him through pine groves and farmland. He breathed in the smell of the trees and the crops. The cool breeze felt good against his face. It would be good to see his father-in-law again.

A rustle in the bushes brought Funakoshi out of his thoughts. Out of the corner of his eye, he saw three shapes half-hidden behind the trees of a small pine grove. Keeping his eyes forward, he continued to walk. Behind him he heard the sound of footsteps on gravel. He stopped and turned around. Behind him stood two men. A third was making his way out of the woods. All three had towels tied over their faces.

Funakoshi stood quietly assessing the situation. They didn’t move like martial artists. They didn’t seem to be trying to surround him. He guessed that they were thugs, not trained fighters. He could probably handle all three if it came to that.

“What’s wrong?” one of the thugs said loudly, approaching Funakoshi with a swagger. “Don’t you have any manners? The least you could do is wish us a good evening.”

“Good evening,” Funakoshi said simply.

“That’s ‘Good evening, sir,’” the other thug said. “Good evening, sir,” Funakoshi repeated.

“Kind of scrawny,” the first thug said, loudly. “He isn’t going to be much of a challenge.” The other two laughed.

“I’m sorry, sir,” Funakoshi said politely. “I think you’ve mistaken me for someone else. I’m not looking for a fight. I’m just traveling to my in-laws’ house in Mawashi. So if you’ll . . .”

“Shut up,” the largest of the three commanded. He picked up a stick that was lying beside the road and slapped it into his other hand. “I ought to beat you over the head just because I find your voice so annoying.”

“You could do that,” Funakoshi answered. “But it wouldn’t prove anything. As you’ve pointed out, I’m a lot smaller than you. You have a stick. I don’t . . .”

“So you’re saying you’re a coward, that you don’t want to fight.” “Why should I fight a fight with such lopsided odds?”

Funakoshi replied.

“Never mind the fight,” said the loud one. “He’s not worth it.”

“Just give us your money,” said the big one, poking Funakoshi in the chest with the stick.

“Terribly sorry,” Funakoshi replied, turning the large pocket in his sleeve inside out. “I don’t have any money.”

“Figures,” said the loud one. “Then give us some tobacco.” “Sorry,” Funakoshi said. “I don’t smoke.”

“No money, no tobacco. Looks like we’re going to have to beat you up after all.” The big thug took a step forward, slapping his stick into his hand.

“Perhaps you’d consider taking these, instead.” Funakoshi held up the small sack he was carrying. The loud thug snatched it out of his hands and peered inside.

“Cakes,” he grumbled. “Is that all?” “Yes, I’m afraid that’s all.”

“Well, I’m feeling generous,” said the loud one. “Get lost, squirt. We’ll wait until next time to beat you up.”

Funakoshi sat with Itosu, his teacher, the next night. They sipped tea together and Funakoshi told him about the thugs he had faced on his way to Mawashi.

“You found a way not to hurt them,” Itosu nodded approvingly. “Good. Very good.”

Funakoshi lowered his head modestly. But inside he was beaming at his teacher’s praise.

“But you lost your cakes,” Itosu observed. “What did you offer at your in-laws’ altar?”

“A heartfelt prayer,” Funakoshi answered smiling. His teacher laughed.

“I think you offered your wife’s family something much more valuable than cakes,” he said, pouring Funakoshi another cup of tea. “You offered them the knowledge that their daughter is married to a good man, one who can protect her if he has to, but who can control himself and his temper even when challenged.”

Funakoshi sipped the tea and smiled.