THE WINTER TERM of 1962 meant getting into Oxford. It was harder for me than for most of my friends in the Upper Sixth because at this point I was confused. My love-life was ahead of those of my friends but my ability to concentrate was shot to pieces as a result.

In those days each college set its own exam. First was Christ Church, which reserved a number of scholarships for Westminster boys. Instead of letting me read up to the last minute, the day before the exams Maro insisted we go to not one but two films, afternoon and evening, in order to make me ‘relax’. And I had to smoke a cigar after dinner. Next day, I sat the exam in the gym at Westminster feeling sick. The silence and the race against the clock just seemed silly.

A fortnight later in the interview at Christ Church, they asked me if I’d accept a place instead of a scholarship. One of the dons was yawning. He’d probably been up all night glossing Euripides. Another seemed to have been felled by a catatonic depression. I looked round and decided I didn’t like any of them, so I said, ‘No.’

Stephen wrote in his diary:

Suddenly I realised that I wanted him very much to go to Oxford, that it is an élite, that his friends Conrad Asquith and Philip Watson are going there, and that if he doesn’t he will be left behind by the best members of his own generation. I felt this specially driving into Chipping Norton to get the Sunday papers. It is a thought that runs contrary to my principles and even my sympathies, but I realised that I thought of my Oxford contemporaries as in some way superior beings. Going there makes one enjoy such conversation and exchange of ideas in circumstances of easy companionship and comparative leisure with the best contemporaries of one’s generation, during their most formative years.

Next stop was Merton, where we had to stay for three days while we wrote our papers. Oxford was cold and bells rang all around us every fifteen minutes. It was a bad winter and heaps of snow turned black with diesel fumes stood endlessly on the pavements, like the grotty graves of scholars. A neurotic boy kept me up all night saying how miserable he was in Scotland. In the interview, I said that I wanted to become a painter and they said, ‘Why not start now?’ The Scottish lad got a scholarship, I flunked.

In the car driving down the Haymarket, Dad told us that I had to concentrate on getting into Oxford. I said I wanted to become a painter. He lost his temper. We got out of the car and Maro tried to quench my hot tears as I blinked up at the billboards of Albert Finney starring as Martin Luther in John Osborne’s play.

Third stop, New College. By this time my father was in a turmoil. I was not to say that I wanted to paint. I was to say I was very interested in English Literature. ‘You have to show them that you’d be a nice person to teach.’ Freddie Ayer was asked to coach me in how to take an interview. He was kind. He was also having an affair with Mougouch at the time, which meant he was interested in the situation. He told me to keep eye contact and answer clearly – it really wasn’t all that difficult.

At my New College interview I was asked by John Bayley what I thought of Walter Pater, and I could manage an answer. I could ‘burn with a hard and gem-like flame’, at least on that occasion. Finally, I was offered a place.

By this time it was mid-January 1963. I felt humiliated. My mother had obviously arranged what she used to call ‘a three-line whip of friends’. What was the point of proving oneself on these terms? Maybe I should have failed five straight exams from December until May by waving my paintbrush in front of those carbuncular professors?

The offer of a place came with a proviso: Matthew must do something about his languages. My mother devised a plan to send me to France to improve my French. I avoided taking a decision and hid with Maro in a flat near Barons Court that she’d just moved into, sharing with Bimba MacNeice and Eliza Hutchinson. Bimba was the daughter of Louis MacNeice, so she was part of the brigade of poetic offspring. It was a great flat. Bimba’s room was wedge-shaped, like the prow of the ship about to sail out of London towards the West Country. Food, conversation, books, sex. Unfortunately, I didn’t bother to tell my mother that’s where I was. I’d assumed she knew. It wasn’t hard to guess. I made a wooden bed for the Pirelli mattress Maro had just bought and painted a small canvas of the roofs of the Queen’s Tennis Club outside the window.

At the end of January, my father wrote a savage letter to Mougouch.

‘I feel I simply must consult you about money. Since Matthew left school I have left his income exactly as it was, namely one pound per week.’ He was prepared to subsidize my stay in France as soon as it materialized. But ‘as far as I can make out he is living as before in the flat of Maro … We have never been told by him that he intended living there, or living separately from us. If he had wanted a room alone we would have been understanding about it and helped him to get one. But I don’t see how we could have financed this arrangement.’

If they intended to live together, he wrote, then Matthew and Maro should pay their own way. ‘It might be quite good for them if they are going to cohabit to realize what the responsibilities of doing this are – that they should support themselves.’ Matthew ought to be in the South of France by now. ‘I am just not going to pay for situations which are presented to me as faits accomplis.’

Here again I hear my mother’s voice speaking through my father. Left to himself he would have realized he was being absurd – an Uncle Alfred complaining about the youth of today. But if my mother complained enough, he’d give in and become a funnel for her anger.

Twice, my father wrote that Mougouch was not to show this letter to us, but she ignored these instructions and handed it over to Maro with one of her grand gestures: make of this what you can. Maro merely read it and put it away. She took it as a straightforward message from Natasha: my mother didn’t want us to live together.

I wondered if I hadn’t hit upon the one thing that would irritate my parents: domestic bliss. If I’d run away to Buenos Aires with a sailor, my father would have understood. If I’d begun to hang out at the Colony Room with Francis Bacon and drink all night, he’d have sympathized, because this was the ‘lower depths’, and therefore creative. If I’d starred in a porno movie shot in a cellar in Soho, he would have been secretly amused, because it would have reminded him of his experiences around the docks of Hamburg when he was young. But happy straight coupledom? No, not that!

At the time I didn’t know about Dad’s obsession with Rimbaud’s ‘derangement of the senses’, but I knew that he hated property and was helpless domestically. The difference between us wasn’t trivial. There was some world-view involved. He thought that art needed a state of permanent unsettlement. I thought – we thought – that houses had their own needs and virtues, so did the streets, and also and more serenely the beaches. Art was in there somewhere, not an inevitable by-product of tidiness but as the flowering of analogy among objects that felt happy with their own weight.

In 1962, the World Marxist Review published an article by Ernst Henri entitled ‘Who Financed Anti-Communism?’ He revealed that the financial backers of the Congress for Cultural Freedom were the Ford Foundation and the United States government. This first article prompted the Irish diplomat Conor Cruise O’Brien to write a hostile review of the 100th number of Encounter. From this moment on, my father’s relationship with Encounter became increasingly equivocal.

On one of my father’s visits to New York at that time, Jason Epstein warned him about the rumours that were floating around in the wake of these articles. The CIA is involved in your life, he said, as tactfully as possible. As Epstein told me recently: ‘All your father said was, “Oh,” in that way of his.’

They were having lunch at the Périgord restaurant, just a couple of blocks from the office of the Farfield Foundation. This entity, owned by Julius Fleischman – his friends called him Junkie – was one of the official backers of the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Many New York intellectuals were sceptical. ‘We strongly suspected that the Farfield Foundation, which we were told supported the Congress, was a filter for State Department or CIA money,’ as Diana Trilling later put it. The title of a book of her essays, We Must March My Darlings, suggests that Diana was cheerfully cynical about left-wing politics.

After lunch, Stephen walked uptown to the Farfield office and talked to Jack Thompson, the man in charge. He was told that there was no truth whatsoever in the rumours. Then Stephen strolled back down to Epstein’s offices and told him what Thompson had said. And that, Epstein told me, was the end of the story.

Epstein liked Spender. ‘A sweet man, and very bright.’ All the same: ‘I always thought that he couldn’t have been that innocent.’

Jack Thompson had been an instructor at Columbia University. He was an expert on prosody and a friend of Robert Lowell. Then Lionel Trilling, Diana’s husband, obtained a job for him at the Farfield Foundation. It’s confusing – if I may cut a long story short. Trilling was supposed to be the great liberal critic of his time, yet many of the neo-cons of the future came from his circle.

I am not a conspiracy theorist and my book can do nothing to calculate the damage done by the CIA’s plot to turn world culture into an instrument of American foreign policy. I am very interested, on the other hand, in the question of who knew what at any given time, because this is a social question. In the USA, the plot involved the universities, the literary journals, the directors of foundations and congresses, the theatre world and the art world. How much was known, or at least guessed, in New York at that time? At those cocktail parties, did everyone know what position his neighbour represented? Was there some overlap between the intellectuals and the intelligence services, as there was in London?

When the American Committee for Cultural Freedom was in one of its perpetual crises about money, its Chairman Norman Thomas was overheard to say, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll ring up Allen.’ Meaning Allen Dulles, head of the CIA. A thousand dollars arrived in the post soon afterwards – perhaps not from CIA funds, for Dulles was a rich man and a personal friend of Thomas since their university days. Diana Trilling thought the money came from the CIA, ‘but none of us, myself included, protested’.

I asked Jason Epstein whether anyone in New York knew Cord Meyer, the man within the CIA who was in charge of cultural affairs. Meyer had begun his career admirably, working for three years with the United World Federalists to consolidate world peace by creating an agreement between the United States and Russia. Only when he realized, at the San Francisco Conference of 1948, that the Russians were using these meetings for the purpose of propaganda did he change his mind. (It was a trajectory similar to that of Christopher Mayhew in England at the same time.)

Epstein spoke to me as if Meyer was someone he’d occasionally talked to, but I had the impression that they did not share the same common ground as existed among a similar circle of people in London. All power in England, political, cultural and financial, is concentrated in the capital, but in the United States there’s New York and there’s Washington and the usual social overlap is not so frequent. However sympathetic Meyer may have been, he was not accessible. Yet, although Epstein’s sense of outrage at the manipulation of culture has, if anything, increased over the years, his sense of recrimination for those personally involved has diminished. The problems of government are huge. Those in charge do the best they can. ‘He himself I am sure was a well-meaning, rather simple-minded guy, as I understand it. He must have thought he was doing something useful, the CIA … I can see why he might have done it innocently, without thinking it through.’

Back in London, my father wondered whether he shouldn’t resign from Encounter. The 100th issue would provide the perfect occasion – with a cover made for it by Henry Moore, obtained by Stephen. Instead, an alternative financing was arranged through Cecil King, the newspaper magnate. Both editors stayed in place; and King got on well with Lasky. Meanwhile Stephen encouraged his friend Frank Kermode to take over his own role.

I remember that at one Sunday lunch in London at this time Richard Wollheim asked my father who actually paid for Encounter. ‘Well, that’s the mysterious thing,’ was Dad’s answer. The backing had been found by Malcolm Muggeridge. ‘Of all people,’ said Dad. Muggeridge was an eccentric author who’d become passionately anti-Soviet during a trip to Russia in the Thirties, where he’d witnessed an artificial famine in the Ukraine created to force peasants into collective farms. ‘Malcolm just said, “Leave it to me,” and in a matter of days, there the money was.’ My father told this as a funny story of no consequence.

Richard Wollheim was a man of powerful but unpredictable opinions. For instance he loathed Parma and adored Padova – or perhaps it was the other way round. He was head of the Philosophy Department at London University, his political views were usually to the left, he’d worked in Field Intelligence in the war and he was fascinated by the Encounter story. At this dramatic moment, he also was asked if he’d like to become a co-editor with Stephen. He looked through the accounts and turned the job down. Years later, I tried to ask him about it. He just smiled. We were out of England by then. He looked around our garden surrounded by olive trees and said, ‘It makes a lot of sense.’ When I asked him what he meant, he just nodded and smiled and said, ‘Just take it from me, it makes a lot of sense.’

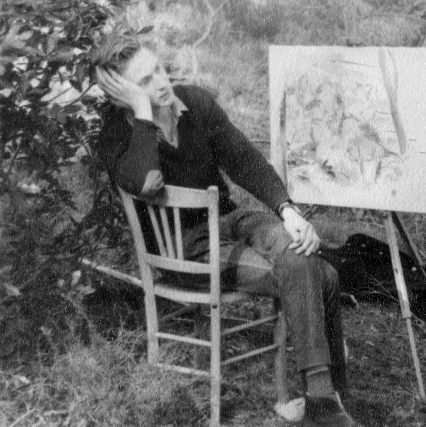

Painting a landscape in the style of Cézanne at the Château Noir, 1961.

In the middle of February 1963, I went off to the South of France with Conrad Asquith, who’d landed a place at Christ Church in hurdle one. We planned to live in Marseilles.

At lunch at Chapel Street shortly before we left, Paddy Leigh Fermor asked whether we knew what we were letting ourselves in for in choosing Marseilles. What if we were accosted by some ‘Apaches’? I said I didn’t know what an Apache was. ‘Come on, Mougouch, let’s show Matthew how an Apache gets his girl.’ They stood up, Mougouch perhaps reluctantly. Paddy tipped out the bread from a wickerwork basket and put it on his head, tilting it forward so that it covered his eyes. Then he stuck a fag on his lower lip and turned to Mougouch: ‘Viens, môme!’ He started pulling her this way and that. ‘Gently, Paddy,’ said Mougouch laughing. ‘You’re going to break me.’ I thought: An Apache routine would be unthinkable at Loudoun Road, and yet Mum thinks of Paddy as one of her oldest friends.

Marseilles turned out to be cold and hard, so we found a room outside Aix-en-Provence at the Château Noir, a big house once used as a studio by Paul Cézanne. The surrounding landscape still held many reminders of paintings by Cézanne: the pine outside my bedroom window, the shimmering trees going up the hill to the quarry of Bibémus, where he’d also painted. I tried to emulate Cézanne: green on green with short sharp strokes, sitting in a path among the pines where the sunlight never kept still. I’d be joined by our landlord, who pretended he was Cézanne’s illegitimate son. Once he looked over my shoulder and said, ‘Ouai, les Anglais sont toujours bon à faire les épinards.’ The English have always been good at painting spinach.

Maro came out for Easter. I abandoned Cézanne and painted two large cheerful images of her in the style of Matisse. We moved to another room in the same Château Noir, where the tachiste master Tal-Coat had worked two years previously. His paint-marks were still visible on the walls. And M. Tessier, the landlord, brought to our attention the fact that André Masson lived down the road towards Le Tholonet.

One afternoon we walked down to see Masson. A maid opened the garden gate and we saw Masson on a deckchair in the sunlight, reading Le Figaro. He got up briskly and came over to greet us. He knew all about Gorky, had met him once, and he looked at Maro with curiosity. I knew nothing about Surrealism at that time. I only wanted to talk to him about Matisse. A shame. Masson was a key figure in Gorky’s life, and we hardly knew it.

At Easter my parents appeared.

If at first sight my mother was displeased to see Maro with me, she didn’t show it. However, a couple of days later, she said that they’d be driving over to see her old friend Anne Dunn at Saint-Estève. They wanted me to come, but Mum said there wouldn’t be room in the car for Maro as well. Maro said: ‘But I know Anne very well. We used to go to lesbian night-clubs together in Paris.’ Mum smiled as if someone had made a bad joke and ignored her.

This left me with the choice of staying with Maro or going with my parents. Reluctantly, under pressure from my father, I went with them. When we got to Saint-Estève, the first thing Anne said was, ‘Where’s Maro?’ I mumbled that she’d been left behind, because Mum didn’t believe they knew each other. Anne said, ‘Is this true, Natasha?’ My mother just smiled and blinked.

Maro went back to London in my absence. She was upset.

After she’d gone, my parents drove to Maussane near Saint-Rémy, where someone had found a Provençal ruin for sale. They took me with them. Mum fell in love with the house and everything was fine, except I was in a foul mood because I felt she’d made me dump my girlfriend rudely and, for all I knew, definitively. My mother just wanted to talk about her plans for her ruin. She sketched on bits of paper while I tried to get her to admit that she’d behaved badly to Maro. A fight broke out. I remember saying, ‘I’ll help you build your house, but don’t expect me to ever live in it.’ Dad just sat there looking embarrassed.

Next morning, Mum behaved as if nothing had happened. My father could afford the asking price of five hundred pounds, so that was that. He called it ‘Mum’s ruin’, as if it was entirely her responsibility. Thus Mum finally acquired the house she’d always wanted – not a honeysuckle-entwined cottage in Oxfordshire with Raymond Chandler in the attic, but an abandoned sheep farm that had once been used for target practice by the Germans.

It was called Fengas, a Provençal word signifying mud. My mother didn’t like this, so she called it Mas Saint-Jérôme, and told the postman and the local tax office. She admired St Jérôme, who in paintings is always depicted as working quietly in his study, sometimes with a lion curled up at his feet.

My mother stuck to that house for the rest of her life. In the autumn she’d drive out from London her oldest friends with whom she gathered her olives. Peggy Ashcroft was one. When the property burned down in a fire about ten years after Dad’s death, she rebuilt it. I kept telling her that she was too old, she couldn’t live alone there anyway, and therefore she should sell it. She paid no attention.

The garden, about which she wrote a book that sold well, measured about seventy yards by thirty. She worked for more hours than I care to imagine on this garden, though the soil was barren and the water source feeble. Into this small space she lavished her love for the gardens of Sissinghurst and Chatsworth and all those other stately homes that she admired so much. She planned an elaborate pathway, and I can hear her voice saying ‘and then you turn the corner and you are in the White Walk’. This was five yards of white flowers. And when Dad said, ‘What will happen if a pink butterfly perches on a white blossom?’, she said without a smile, ‘Oh I don’t think that will matter, do you?’

She called her shrubs by their Latin names, and they cowered. My father said that whenever shrubs in the local nursery heard they’d been chosen for Lady Spender’s garden, they’d start trembling, as if they knew they were destined for a concentration camp. He did not love that house, but he never told her. In summer it was so hot he couldn’t work, and it was bad for his heart, but he never refused to go and he pretended he was happy there. That house was his penance, his cure.

When Lizzie and I sold it after her death, a strange thing emerged. The caretaker, a sweet Provençale woman, said that Mum had told her that she’d suffered very much as a child, because her mother had been a gambler who’d lost all her money at the Casino; thus they’d been miserably poor. This was exactly the story of the caretaker’s mother. It was a case of Mum trying to show sympathy by telling a lie. When I said, But our grandmother never gambled, the caretaker just gave a little nod. She hadn’t believed my mother, because the story was a mirror of her own. She did not hold it against Mum, for she knew she’d lied in order to be friendly. It was a moving example of Mum’s capacity to use those different voices that she’d learned in her childhood. Reality could be reassembled to fit the other reality of people’s feelings.

After my parents had gone back to London, one evening as I rode my motorbike back up the hill from the bar at Le Tholonet, looking up at the full moon and thinking how beautiful life was, I ran slap-bang into a telephone pole. I was chipped and churned and the bike refused to go up hills after that.

It was a seven-mile walk into Aix for the groceries and seven miles back. Once I was so hungry that when I got home I cooked and ate the entire week’s provisions.

The market lay beyond the barracks. The French Foreign Legion had recently been recalled from Algiers. The war was over at last. Tough-looking soldiers stood outside in the street with their hands on their hips, glowering at the citizens of France who’d betrayed them.

Missing Maro, I hitchhiked back to London.

Chapel Street had remained the centre of Maro’s existence for some time after she’d moved into St Andrew’s Mansions. Then one day Mougouch had said, ‘Off you go, dear, back to your little world of Barons Court.’ This so annoyed Maro that, indeed, her psychological base switched from her mother’s kitchen to St Andrew’s Mansions, where a huge map of Europe was hung as a curtain over the window in the kitchen, with ‘Greater Armenia’ on it, taking over most of eastern Turkey, northern Iraq and western Iran.

I was in London secretly, so I went to a theatrical store and bought myself a big moustache, larger than Hitler’s but smaller than Stalin’s. I thought it would provide anonymity. One evening we all went to a play. I knew my parents were in the audience, so I hid behind a pillar. Bimba’s father Louis MacNeice was also present. When she brought him over to show me in my splendiferous mustachios, he murmured, ‘It’s nice to see a Spender with a sense of humour.’

For some reason this remark got to me. It was the first time I had an inkling that among my father’s generation, among his immediate peers, there were those who did not see him as an eminent figure.

I went back to France a few days later. As I left, Maro took all my cash off me as rent. This was the result of the secret letter that Stephen had written to Mougouch saying we ought to be serious about money. I told Maro that I couldn’t exactly swim the English Channel, so she gave back just enough for the boat ticket.

In France, I slept for the first night under the marquee of a wedding in Calais, which I found by mooching about aimlessly in the suburbs; and the second night in an orphanage in Clermont-Ferrand, which I found by asking a gendarme. I was very hungry by the time I got back to Aix.

I went up to New College that autumn.

There’s not much to be said about my Oxford career except that it was squalid. I was not depressed, in fact away from Oxford I was very happy, but I knew I wasn’t doing my best with the opportunities the university provided. I did not want them. On the other hand I could not do without them. Westminster had given me the appetite. I was in a bad way, because I felt that the opportunity to go to art school had come and gone and that every step I took towards Oxford took me away from art.

From the rooms in the Old Quad that I shared with another student, we looked down on the Mound, an incongruous heap of vegetation surrounded by an immaculately razored lawn. I got into the habit of climbing out of college at dawn to paint a cypress tree in the local cemetery. Over time, the tree withered under my gaze. Back for a quick lunch of beer and a pork pie, a snooze, then at three in the afternoon my academic life would start. I knew how to write an essay. I should have been finding ways to feed this skill imaginatively, but I simply turned it into a vice. I gutted books and wrote my lines and that was that.

I did not join any societies, I did not go to lectures and I did not eat in Hall. Instead, I joined the Ruskin School of Drawing and drew nudes. I read catalogues raisonnés in the library of the Ashmolean Museum, vast tomes with no colour reproductions, but the black and white photogravures had a solidity of their own. The Ashmolean owns the beautiful Piero di Cosimo of a fire in a wood, hung not far from The Hunt by Paolo Uccello, among whose dark trees the strident riders reminded me that in Italy nostalgia is not ornamental, it is an attribute of nature.

I studied Japanese prints. I went to the Victoria and Albert Museum and arranged to guide tourists, but the Proctors heard about it and politely told me that I couldn’t study at Oxford and earn money in London at the same time. While in the V&A, the Keeper of the Print Room took me to one side and said that I should change from Modern History to Japanese at Oxford and come back to him in three years’ time. ‘You could carve out a nice little niche for yourself here at the V&A.’

At the end of my first year, I earned an Honorary Exhibition. My essay on Bishop Anselm had apparently made an impression. No money, just a fluttering gown. My friends heard the word ‘exhibition’ and thought it was a show of my paintings, but these were getting smaller and tighter and more antique by the minute. Meanwhile the cypress tree tilted over on one side and was fenced in by ropes.

In the interest of making us all get on better, I asked Maro to turn off her natural instinct for contradiction whenever we went to Loudoun Road. Couldn’t she just sit there and listen, for once? ‘I can’t,’ she said. ‘Conversation is supposed to be a ping-pong. But with your parents, it’s all ping and no pong.’

One supper during my first year at Oxford, we went there for supper. The other guests were Auden and Freddie Ayer, who’d written a brilliant book on Logical Positivism that neither of us had read.

Auden at table wasn’t the easiest of guests. His presence was benign, but he smoked between courses, wasn’t interested in the food, and when he spoke he was oracular rather than conversational.

On this occasion, he announced that often one pretended to have read a book, even though in fact one hadn’t managed to get through it. The worst was to have written a review of a book before reaching the last page. That was ‘naughty’. He liked the idea of rules and morality, and this occupational hazard, which must face all book reviewers – and there were two others at the table – obviously broke an important rule.

‘For instance,’ he added, ‘I never got to the end of The Alexandria Quartet, even though I gave Durrell a good write-up.’

Before Freddie or Stephen could say anything, Maro said that the great thing about Lawrence Durrell’s novels set in Egypt was the descriptions of the city and the feeling of being a European exile in Alexandria – though he wasn’t so good on the subject of the Egyptians themselves.

Then it was Dad’s turn. He said he’d never seen the point of Rabelais. ‘But have you read him in French?’ said Maro quickly. ‘The way Rabelais describes food is marvellous, but it doesn’t come out so well in English. And anyway, the English aren’t interested in food.’

No, said Dad heavily, he had not read Rabelais in French.

Finally it was Freddie’s turn. Freddie said that he’d never managed to get to the end of Don Quixote. Maro started saying something about the emptiness of the Estremadura and Dad turned to her and said, ‘SHUT. UP.’ It was so emphatic, the full stop was audible between the two monosyllables.

So Maro shut up. She didn’t seem discouraged, though. She’d read the books. The others hadn’t. Why shouldn’t she have chipped in?

Not long after this, we were having supper at Loudoun Road when the subject of the origins of language came up. Before anyone else could say anything, Maro said that the origins of language were obviously onomatopoeic. ‘The Chinese word for strawberry will be like the noise of a Chinaman eating a strawberry.’

Unfortunately, one of the guests at table was a professor of philology. He tried arguing. She persisted. He lost his temper. Nothing was more simplistic or inaccurate than what she’d said. The origin of language couldn’t be reduced to the imitation of natural sounds.

Maro backed down, but she happened to be sitting next to my mother. In a kindly but persistent way, Natasha whispered to Maro that if one were sitting at table with a distinguished professor, one really had to pay respect to his superior knowledge. I saw Maro’s face begin to crumble. Next minute, she was going to start crying.

Before this could happen, I rose from the table and said I really had to get back to Oxford. I had a train to catch. She and I got up. The professor started to apologize, but I said Never mind I really do have a train to catch, I’m sorry to break up the dinner party, please don’t mind us.

In the street, I tried to take my mother’s side. Couldn’t Maro just keep quiet whenever we went to supper at Loudoun Road? She said, No. Well, couldn’t she at least think before she spoke, I said bitterly? ‘No,’ she said. ‘How can I tell what I think until I’ve said it?’

If that was her attitude, why had she become so upset? If she’d ignored the social customs, she had to take her chances. She said, ‘But under the table your mother was pinching me!’

There was no answer to this.

‘I can’t stand your mother’s respect for academics. That professor,’ said Maro. ‘He was just arguing with the argument. That’s what professors do. They squibble. But let’s not talk about it any more. I’m so tired, I can feel my eyelids creaking.’

It was a long way back to Barons Court.

‘Oh, your mother,’ said Maro as we went to bed. ‘I refuse to be figged and I refuse to be tossed by her.’

We stayed away from Loudoun Road. It was for the grown-ups to defuse the situation. No incoming calls came through, however. I brooded. Still the telephone kept silent. Was Maro right? Was there something remorseless about my parents?

Many years later, on one of our ‘honeymoons’, when Dad and I went off together in order to bond in the absence of our wives, I mentioned the strawberry incident. Dad remembered it, and he added a detail which made me posthumously furious, as it were. He said that next day the remorseful professor had sent to Loudoun Road a big bunch of flowers with a letter of apology addressed to Maro.

‘Why didn’t Mum send them on?’

‘Natasha thought that it would spoil Maro.’

I looked at Dad, dumbfounded. If Mum had stuck to the rules, the flowers would have been received, Maro would have written a note to the professor, and the incident would have been closed. Why hadn’t he insisted that Mum send them on? He whose manners were so perfect?

‘Yes, I feel very badly about it,’ he said, trying to disengage.

These incidents carried a weight out of all proportion to what had actually happened, because my mother always insisted that Maro had to learn from her mistakes. I’m sure that in the eyes of almost anyone, we were behaving badly. We were over-privileged and familiar and casual – I plead guilty to almost any reproof regarding my earlier self. But my mother took the view that we were all of these in relation to standards cast in bronze. It was this faith in her own rightness that made it so hard to talk to her.

Dad came round to Maro in the end.

It happened that one day he complained because someone had sent for publication in Encounter several poems written by an Eskimo. What could he possibly know about Eskimo poetry? Maro said, ‘But Stephen, surely you know that marvellous Eskimo poem that goes, “Granny, you are too old. It’s time we put you on to an ice floe and pushed you out to sea.”’ Dad almost broke a chair laughing. Maybe it’s what he’d always wanted to do with his mother-in-law, Ray.

While I was in Oxford keeping my head down, Bimba took Maro up to Hampstead to meet Bill and Hetta Empson.

My father probably met William Empson in the mid-Thirties through the Mass Observation project, where Stephen’s younger brother Humphrey worked – as did the second husband of Inez Pearn, Stephen’s divorced wife. Then Empson left England to teach in China, whence he returned shortly before the war. He went back to China to teach at Peking University after the war, and when he returned to London he gave the impression that he’d become a sympathiser of the Chinese Communist Party. Stephen admired and liked him, but there’d been an estrangement that had taken place soon after Encounter was founded.

In 1954, at a party given by Louis MacNeice, Bill had cornered Stephen and accused him of having ‘taken sides’ in the conflict between America and the communist bloc. Stephen explained that he considered that Encounter was ‘a platform in which American points of view confronted and were confronted by opposite attitudes in other parts of the world’. Bill told him briskly that, if this was his intention, he’d failed. Others at the party tried to defuse the situation. Someone said that Empson was on such good terms with the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party that the wisps of his beard communicated with them directly by radio. The confrontation got worse, and in the end Stephen threw a glass of wine over Empson. Bill was good about it. He said there were so many stains on his suit, one more wouldn’t matter. Since then, however, the two distinguished authors had been on ‘non-speaks’, as the expression of the time had it.

Bill Empson lived in a nimbus of his own, but he didn’t insist on deference if he threw out fragments of his thoughts. I remember one afternoon when he tried to convince his son Mogador that what the Chinese really needed was cheap timber for coffins, and he should buy lumber in Canada and set up a carpentry shop. Wearily, Mog waved his hand.

Meals at the Empson house in Hampstead were cheerful mayhem. There was none of the respectful hush that my mother cultivated at Loudoun Road. If what Bill was arguing became too arcane, he spoke to the ceiling and the rest of the table went on rowdily saying whatever came into their heads. Once, Hetta leaned across me and said something particularly intense to Mogador, in Chinese. I asked for a translation. Mog said calmly, ‘She’s just told me that I’m an unspeakable mountain of shit.’

Hetta was what used to be called ‘a free spirit’, but the scale of her freedom was so grand it made most other bohemians look shifty. I remember dancing with Hetta once, and soon she was clasping me in a tight clinch. I think this must have been at the Round House at one of those dance-and-poetry readings. I didn’t know how to cope, so I said, ‘Hetta, not in front of them.’ She looked over to where a neatly dressed couple was watching us curiously. ‘What’s the matter?’ said Hetta. ‘You owe ’em money or something?’ I said, No. ‘Well then, fuck them.’

With what contempt Hetta cornered one of Bimba’s boyfriends and said, ‘Don’t tell me you’re a Trot.’ In London at the time, to be a follower of Trotsky signified an intelligent approach to communism – but not to Hetta.

I think it was driving in a taxi to another gig at the Round House that Bill leaned across Hetta and tapped me on the knee. Does Stephen know he’s working for the Americans? Flustered, I said I wasn’t sure. Bill started to expand on this warning, but Hetta interrupted saying he shouldn’t interfere. What have Matthew and Maro got to do with it?

I told Mougouch about this strange remark. She said, ‘He probably means that Encounter is paid for by the CIA.’

‘Is that so? You seem to take it for granted.’

‘Everybody’s known about it for years.’

‘Everybody? My father doesn’t,’ I said. ‘So, if I may ask, how do you know?’

She puffed at her cigarette. ‘Maybe John Gunther told me.’ This was a famous journalist of his time, whose ‘Inside’ books had provided American readers with intelligent observations of countries in Africa and Europe. His wife Jane had known Gorky since the mid-Thirties. ‘I can’t remember who told me. How funny that Stephen says he doesn’t know! I can hardly believe it.’ Another puff. ‘And Junkie’s an old friend of ours.’

‘Ours? Junkie Fleischmann is a friend of the Magruders?’

‘A friend of my uncle Sidney’s,’ she said. ‘I saw him as a child when I went to Ohio. He’s a very friendly person. Everybody liked him out there. And it wasn’t a secret, what he was doing. They all said how sweet it was that he enjoyed working for the State Department.’

‘What! Your uncle Sidney was a friend of Junkie Fleischmann?’

She told me that her uncle Sidney Hosmer, her mother’s brother, came to a sad end in about 1942. He ran away from Ohio to New York and she and Gorky had had to take care of him. He was an alcoholic, ‘Wouldn’t you know?’ And one day he was mugged and ended up in Bellevue among the loonies. She took him a pair of Gorky’s pyjamas, for he had nothing – and there was nothing to be done. He died a short time later, still in Gorky’s pyjamas.

‘Please! So you knew Junkie Fleischmann as a child?’

Her father Captain Magruder had resigned from his club at Newport, Rhode Island, because they’d refused to serve his friend Junkie Fleischmann, on account of him being a Jew.

‘We all got up in a flurry of dignity and my father said that if Mr Fleischmann was barred, they could do without the Magruder family, too. And so we left. I remember, because I was hungry and I didn’t understand why we couldn’t eat first.’

I felt dizzy. This was what Maro and I used to call a ‘short circuit’, meaning one of those moments when her world and my world turned out to be too intimately connected. It always made me uncomfortable. I didn’t want us to be all riding along in the same machine.

Maro and I were beginning to feel that our lives were much too dominated by the previous generation, whose mixture of approval or disapproval seemed to have no connection with the high-minded world they were supposed to represent.

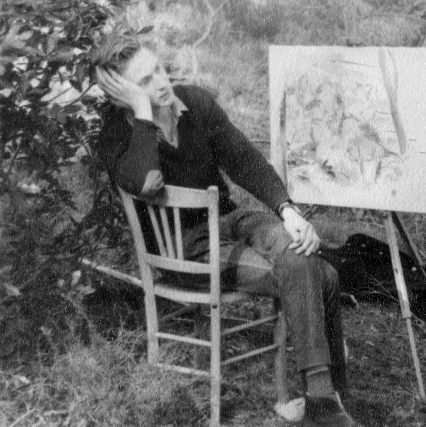

A literary party in the early Sixties.

Upstairs, Louis MacNeice chatting to W. H. Auden, who’d asked especially to see him – had telephoned from New York to arrange this supper at Loudoun Road. Wystan had been ready for hours in the piano room before Louis, tall and pale, arrived.

Leaving them to it, we could hear the boom of Wystan’s voice from up above, while in the kitchen my mother was being helped with the supper by Chester Kallman, Auden’s companion, and Sonia Orwell. Sonia and Chester were both sweet people but they brought out the worst in each other.

‘I mean it’s become absolutely impossible to talk to Louis,’ said Sonia, stirring a pot. ‘He’s completely sold his soul to the BBC.’

And Chester egged her on. He disliked London, where he could appear only as second fiddle to Auden, a role that understandably he detested.

At that moment Louis walked in. He asked for an ashtray.

Of the occupants of that tiny kitchen, was I the only one to feel shame? Was this the dark side of having a reputation? If so, it did not seem worth it.

My father disapproved of Chester. He thought he treated Wystan badly. Indeed, Chester was chronically unfaithful. A story Dad told several times was of sitting in a square with Chester and Wystan, then Chester saw a handsome boy pass by, got up and followed him. Wystan went on talking in a completely normal way, but my father noticed that he was weeping.

Chester knew more about opera than Wystan, at least at the beginning. Chester’s advice was essential when Wystan came to write the libretto for The Rake’s Progress. Thus we have one of the strangest stories of twentieth-century creativity: one genius, Stravinsky, leaning on another genius, Auden, leaning on Chester Kallman – who, loveable though he may have been in many ways, would surely qualify for a World Prize as Broken Reed. Chester didn’t believe in heterosexual love. As a result it’s absent from The Rake’s Progress, which is in all other respects a masterpiece.

Dad disliked this opera, and he took it as evidence of Chester’s underlying frivolity. In a moment of irritation he said to Wystan, ‘You could leave him, you know. There must be plenty of other people who’d love to live with you.’ Wystan just shut his eyes and murmured, ‘Schluss.’ Meaning, the argument is closed.

Yet Chester always got on well with Maro and me. Perhaps we felt a similar unease with London life. We once met him outside a grand cocktail party. ‘Hello Maro, hello Matthew,’ he said – and we were pleased he’d recognized us, for we didn’t see him that often. ‘My first instinct in these kind of things is to flee.’ For us, the perfect remark.

About a year after I’d been living with Maro, I showed Wystan a poem. It was about the images that went through my head when I was fucking. Since my only love at the time was Maro, showing him the poem was also a provocation.

If I’d expected a comment on our relationship, I was disappointed. He read it through fast, once, and handed it back saying, ‘It’s a good poem. Ah – perhaps too many hyphenated words; but no, it’s a good poem.’

Anyone else would have been thrilled to receive praise from W. H. Auden but for some reason, I wasn’t. I’d wanted to hear what was wrong with it, followed by a lecture about what a poem should aim for. To have written a poem that was merely ‘good’ deflated the whole thing.

Towards the end of the Sixties, Auden began to withdraw into himself. Many forms of social behaviour became harder for him. He could foresee the end of a story long before it arrived, and would start saying ‘ya, ya’ halfway through. It required persistence to talk through this barrier. You thought that what you were saying was banal, or that he was bored, or both.

My parents did their best to force him to participate. There was one joke which I must have heard Auden tell half a dozen times at the dinner table, encouraged by Dad. It was about Wystan and the sadomasochist. The punchline was, ‘I’m no boy scout, my dear. I can’t tie knots.’

My mother told me that when they were alone in the house he’d start breakfast with a list of the things he was grateful for. It was a litany he had to recite, she said, before he could face the day. It was almost a prayer.

Wystan’s aura of solitude was tempered by his love-thy-neighbourliness, which nearly overcame it, but this was expressed in flashes that were thrown out briefly before he subsided again. Pills and alcohol had worn him out. Uppers in the mornings, downers at night and alcohol in between. He thought of his mind as an engine that needed an engineer. He switched himself on in the mornings and off again at night. The pills were the switches.

His huge mouth gobbling pills, lower lip flapping, elephantine, washing it down quickly, with an air of There, that’s that. Now I’m ready. Now I’m done.

‘Wystan thinks he’s going to live till he’s eighty,’ said Dad, who’d spoken to Auden’s doctor in New York. ‘The trouble is, he IS eighty.’ In fact, Auden was not much older than sixty at the time.

Among themselves they talked about death as if it was another prize they were all aiming for. I remember Wystan telling Dad, ‘My dear, you’re the one who’ll have the last word. You’re going to bury us all.’