IN SEPTEMBER 1964, my mother was diagnosed as having cancer. She had to have an operation immediately.

I heard this news at the Marlborough Gallery during the opening of an exhibition of recent work by Francis Bacon. I was standing in front of Man on a Bicycle. Sonia Orwell was just that minute saying intently, ‘At last Francis has managed to paint a cheerful painting.’ Then I was called outside. My father was in tears. He did not use the word ‘cancer’. He just kept repeating, ‘Afterwards the doctors say she’ll be able to lead an absolutely normal life.’ I couldn’t understand what he was talking about. I assumed that Mum was about to die. My only reaction (I’m ashamed to say) was selfish: She’s done what she was put on the planet to do, give birth to me.

We now know from her letters to Raymond Chandler that she’d been suffering from a physical ailment for years. Whether this had any connection with the cancer, I do not know. My mother was incredibly secretive about her illnesses. She didn’t want any of us to know, and she insisted then and for several years afterwards that Lizzie and I weren’t to be told that she’d been operated on for cancer.

Though Dad knew that my mother had problems with Mougouch, he came to Chapel Street to talk about it. Mougouch offered to help. He said, ‘Well, if you could do something about the garden.’ Mougouch’s only garden was a bay tree in a wooden tub on the roof outside the kitchen at Chapel Street, but she telephoned for some professional gardeners and she paid the bill.

My mother had always neglected the garden at Loudoun Road, because the house was rented and she didn’t think of it as being hers. She lived in that house for nearly seventy years and she never spoke of her potentially beautiful garden as being anything but a ‘problem’. Seeing from the piano room window how nicely it was coming along, with three gardeners turning it into a little gem, my father telephoned Mougouch and asked her (and Maro and me) not to mention to Natasha, when she came back from the hospital, that Mougouch was paying the bill. It would upset her, he said.

I said thank you awkwardly to Mougouch several times. I felt ashamed. She thought it was rough, but she pushed Mum’s garden on to one side and told me briskly, Don’t worry, Natasha will recover. ‘Most women have to go through that kind of an operation,’ she said. She herself had been told that her womb was a ‘leathery old thing’ which would have to come out sooner or later. This reassured me, because it was so matter-of-fact.

During this visit, Dad told Mougouch something so strange that she didn’t pass it on to me for several weeks. ‘We Spenders have always succeeded in killing the women we love.’ To her it was meaningless but maybe I could make something of it. She raised her eyebrows and looked at me full in the face, her eyes particularly green. I said that I thought it might have something to do with the death of his own mother; but he’d also placed himself in the forefront of what was surely my mother’s problem, not his. She nodded. ‘We can forget about it,’ she said decisively.

On the day after the operation, in bed and presumably still under the influence of morphine, my mother had an experience that she treasured for a long time.

The magic of that day in the hospital – trussed up to machines – one of which made a noise like a motor boat going round a Greek island, and absolved from all duties, guilts and exertions. Peacefully listening to the sounds – suddenly from the pretty little Victorian garden below my window, with its little drinking fountain with tin cups attached on chains – a sound of many rapid pattering feet – scuffles rattles of the tin cups on their chains – a multitudinous sound like a flock of chattering birds – more pattering of feet departing, and then a clear solitary silver voice of a young child – saying ‘You fucking bastards – why can’t you wait for me?’ I thought I had never in my life heard anything so beautiful as that little voice.

She decided there and then that she should treat every subsequent day as a gift, to be treasured as if it were time acquired in the face of death. She wrote this entry in a moment of depression, when she’d let herself in for the trip to California to meet Bryan Obst, my father’s last lover. She was counting up the moments in her life that she valued, and this was one of them. She noted that in the South of France where she was brooding, sometimes the days came and went without anything happening at all. ‘Yesterday’s accidie [laziness] therefore is inexcusable, according to my “every day is a gift”.’

Sonia was ready for her when she came back from the hospital. She’d primed my father on what he had to do. When Mum came in, Sonia hissed: ‘The flowers, Stephen, the flowers.’ Dad produced a big bunch of flowers and offered them – to Sonia. ‘Not to me, you fool! To her!’ Mum staggered through this scene and went straight upstairs to bed.

My mother was told that she’d never be able to perform a concert again.

She didn’t touch the piano for two years. Not only that, but she refused to go to concerts, or to the opera, or even listen to music on the gramophone. My father was shocked. This made me feel that either he didn’t know about music, or he didn’t know his wife. It seemed to me utterly reasonable to dump the whole thing. No second best! No tinkling the ivories between cooking his meals! That’s what she’d always said. Did Dad think she didn’t mean it? Or had he never taken her music seriously to begin with?

Not being able to perform meant that Mum had to give up the camaraderie of the musical world, with its feeling of ‘let’s row this boat ashore’ that performance entails. She never said that she missed it. On the contrary, she always implied that the world of music, except at the very highest level, was limited. But, without her career, she had to face the reduction of her sense of self to that of housewife and helpmeet. Silence was never so precise as in Loudoun Road thereafter.

Over the winter, my mother did her best to pull herself together after the operation.

In Dad’s study I overheard her tell him: ‘One has to be so careful in this second chance sort of life. One can’t risk making any mistakes.’ A touching remark. But I brooded about it. Wasn’t there a kernel of ambition in there somewhere? Didn’t it mean that she wanted to recover, catch up, overtake, succeed?

Over the winter, she decided that she’d go back to university and start again. Richard Wollheim at London University was encouraging. She started learning Latin from scratch for an O level; and she’d certainly manage music A level, even though it meant studying a symphony by Sibelius that she hated. A group of Auden’s poems was set for her English exam. The next time he turned up at Loudoun Road, she handed them to him for the latest corrections. I remember seeing ‘Spain’ with a vertical line crossing out the whole thing.

The second interesting remark that I overheard occurred during a private conversation between my mother and Sonia. After one’s body had been so martyred, Mum said, there’s no question of taking on a new lover. It’s hard enough to retain the lover one has, and then only because he recognizes what he used to love.

To me, this was a very unexpected remark. I’d assumed that the big difference between Mougouch and my mother was that Mougouch was inside the world of love affairs, Mum wasn’t. It suggested that, however faithfully my mother remained loyal to her ‘discipline’, the idea of a new love had survived until then, ticking away somewhere in the back of her mind.

In the early summer of 1965, when he was fifty-six years old, Stephen met and instantly fell in love with Nikos Stangos, a young Greek poet working as a press attaché in the Greek Embassy in London. Twenty-eight years old, Nikos was slim, curly-haired, well read and brilliantly intelligent, but touchy. It’s a quality I’m grateful for. In Stephen’s love letters to him, time and again he has to explain what he expects from love.

They’d hardly met before they were separated by the summer holidays. From 23 July, Stephen and Natasha were in the South of France, where my mother struggled with her Provençal house. Maro and I joined them there for a week. Mougouch had told Maro that she mustn’t mention the word cancer to me, as Natasha wanted to keep her operation secret. Mum wanted to seal the floor of the kitchen with a polish called Starwax that she’d brought out from England. She became fanatical about spots on her kitchen floor. Maro layered that floor daily with Starwax, but she wasn’t pleased that Mum persistently called her by the name of her Portuguese maid back in London.

As part of me was still a sulky adolescent, I thought the tensions in the house were normal, so I hid in the bedroom. But there was one evening when my mother went wild and escaped across the hillside. Perhaps she’d guessed something about the still invisible Nikos. We all went out to look for her, Dad included. We’d never have found her if she hadn’t said, from beneath a Provençal rock, ‘Go away.’ My father told us gently but firmly that he’d deal with the situation now. So Maro and I wandered back to the house. As usual, my parents kept their problems to themselves.

Stephen tried to nurture his relationship with Nikos with letters. Fantasy fuelled his patience during a long, difficult summer. ‘Now what I would like is that we always – or for a long long time – regard one another with the same affection and consideration. Which means that during the next year or so, we must accept intervals in which we write to and think of one another.’

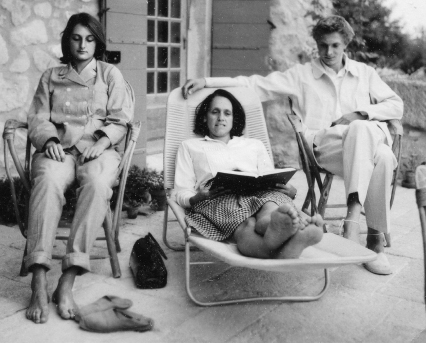

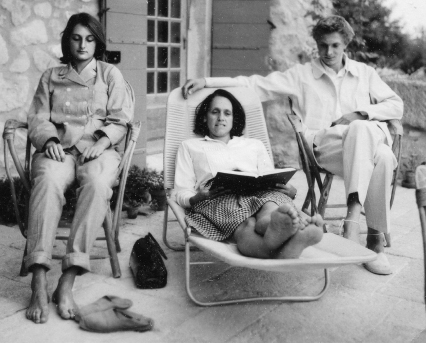

Maro, my mother and me at Saint-Jérôme in the summer after her operation.

He longed to see Nikos again, but between the end of the summer and his departure for Washington in October, there wouldn’t be much time. He arranged for them to spend two days alone and built fantasies around this expectation as my mother struggled with her garden – that barren patch of land desperately needing to be fed. And the water problem. And the builders. But she was determined to make that house work – because, unlike Loudoun Road, it was hers.

In England, over the weekend of Friday 3 and Saturday 4 September 1965, Stephen joined Nikos somewhere in Sussex.

They drove back to London on the Sunday, stopping for a walk along the Sussex downs, where they sat and talked under some trees on a low hill. Stephen asked Nikos about his relationship with a friend. ‘That is a pornographic thought,’ said Nikos sharply. Later, Nikos rolled down the hill, which Stephen thought was a magnificent gesture. It was a curious two days. At one point Stephen had to make a detour and speak to Malcolm Muggeridge. He left Nikos outside in the car. The weather was also strange, glowering as if to send them back to the city, then brightening up.

Driving towards London, Nikos told Stephen of a recent dream that had disturbed him. Stephen kept thinking about it.

When you are relating a dream as you did on our drive home, or when you explain your attitude to poetry, or when you write a letter then I think you are a writer, as Proust was, perhaps. Now I know I’m taking terrible risks saying this, but it is said out of my love for you: which means that I am not pressing you in any way with my opinion, but giving it because you want to know what I think, giving it so you may reject it instantly.

Less than a week later, Stephen flew to Washington to take up his job as Poetry Consultant at the Library of Congress. He was required to be in an office from nine to five, preferably writing poems. ‘There is something too creepy about the idea of the official poet sitting in his office really writing poetry. The idea of “behaving” exactly to fit an allotted role is a bit mad really, like a depressive maniac really looking depressed.’

His fantasies about Nikos balanced the absurdity of his official duties. And so, back again to that meeting in Sussex: ‘I must try and think about that day we had on the downs in a way that makes it not just a recollected happiness but a present one, which it is.’ In his mind, he went over everything he’d said to Nikos, regretting that he hadn’t been clearer on some points, continuing the discussion of others. ‘I thought always that if we were alone for two days every minute would count as an hour and there would be moments we would keep for the rest of our lives. This really is so, and I thank you more than I can say.’

Nikos had a distinctive voice: precise, with a faint touch of bitterness. Stephen’s imaginary conversations were real to him because he could hear that voice in his mind. Sleepless in Washington: ‘During the night I was trying to explain to you that when I asked you about you and Nickyphoros and you said “that is a pornographic thought”, somehow I adored your saying so in that way too much to explain that really I meant something quite different which was: “is what we really want more than anything with each other a passionate conversation?”’

Nikos often responded sharply to Stephen’s interpretation of his personality. He was good at reading between the lines and detecting hidden drops of poison. It was maddening for Stephen to have to keep apologizing for having insulted Nikos, but Stephen longed to forgive him. ‘You always relate everything to some standard which is marvellously clear and pure in your mind. When you say things which seem severely critical I can recognize the truth in them and feel that I was longing for them to be said. That is partly of course in the way in which you say them.’

Because so much had been left unsaid, that one memory could become a creative fuel. ‘I found what you said in the car very convincing. You think of me as judging or as untouched. The position really is that I am anxious to learn … I would like to say to you “please write more poems so that I can learn from an act of writing of a kind which has been blank for so long in me”.’

This, I think, is the key. The afternoon with Nikos on the Sussex downs was elevated by Stephen so that it became a kernel of experience, of the kind that his poems came from. Over and above whatever he loved or expected from Nikos, Stephen hoped that he himself was still capable of the intense feelings from which a poem springs.

Let me try to sum up my father’s expectations from love.

There are many clues in this book that Stephen had doubts about the reality of his own feelings. He always insisted that he was the victim of his friends; had no will of his own; had doubts about the condition of love. Auden had said, early on, that this was all untrue: Stephen needed love as much as anyone else, but he didn’t want to reveal the fact, because it would make him vulnerable to others.

In the earliest phase, when at Oxford he was in love with a young man he calls Marston in his first book of poems, the love object was untouchable. Wystan blasted Stephen out of his hesitation. The second phase, the boys from around the port of Hamburg and from the Lokalen of Berlin, was complicated. There was sex, and there was an attachment of sorts, although this love was linked to The Temple, the polemical book that Stephen wanted to write about the experience, and to his need to prove something to himself and to his friends.

When he met Tony in 1933, Stephen recognized an amalgamation of sex plus intelligence and he chose it instantly. It was a courageous attempt, but unfortunately Tony lived only for the moment. He had no other dimension, clever though he might have been. It was impossible to live with Tony, because he required constant attention of the kind that would drive anyone insane. And so Stephen counted out for ever the possibility of living with another man. Two men in one apartment would always disagree, because each to the other was, as he’d once put it, ‘a substitute for something else’.

There followed the relationships with Muriel, Inez and my mother.

In his relationships with women, I think my father’s sense of pity predominated. He could empathize with a woman’s unhappiness, but it also made him panic. This reaction perhaps went back to the lack of sympathy he’d shown to his mother when she was about to die a miserable death, a rejection of unhappiness as a rejection of death – but this is to drift into psychological areas where I’m not qualified to have an opinion. Suffice it to say that he could offer sympathy to a woman if she were unhappy, he could tune into that unhappiness to a remarkable degree, but to help her do something about it was beyond him. The most he could feel was helpless, because he had no will of his own.

Sympathy and good manners are excellent virtues for a long and solid marriage, but they lack the vital element of desire. Inez, recognizing this, left. She reclaimed her initiative. My mother was tempted to leave, but a) the tempter (Raymond Chandler) was physically unattractive (and off his head), and b) she truly enjoyed the creation of a home, plus status, which marriage to my father brought with it.

When Nikos came into my father’s life, Stephen opted as soon as possible for the solution he’d already found by trial and error with Reynolds Price: the young man as a source of inspiration, the creator of events that might crystallize into a poem. However physical his relationship with Nikos may have been (and I have no information about this), Stephen wasn’t going to run away from Loudoun Road and live with him.

Meanwhile, because these feelings were so heavily imbued with fantasies that were not his, Nikos resisted any of the attributes that Stephen wished on him. Nikos insisted he was a real person, not a pretext for a poem.

In spite of my dislike of Oxford and my waste of its benefits, my academic interests refused to die. I took Dante as a special paper, on the grounds that I’d never read him otherwise. It was hard work, made harder when Maro came down for the day and read the whole of the Inferno in one go, sitting in the Radcliffe Camera in a ray of sunshine. She said she liked it. I felt helpless. Liking it wasn’t part of what I needed to do with it.

I took a special paper with Edgar Wind, whose lectures on the Sistine Chapel I’d admired. ‘Here vee see zee dagger sretning zee örthh.’ Was that supposed to be, ‘threatening the earth’? He thought that Michelangelo was a follower of Savonarola. (I’ve since been told that he fudged the evidence.) He wore his spectacles on the tip of his nose and he had a long stick to point with, and I thought he was a kindly man. I knocked on his door and asked to join a class he was giving to postgraduates. I wasn’t eligible, but he let me come anyway.

The class was on the Discourses of Sir Joshua Reynolds. This was the attempt by Reynolds to create an art-loving public in England in the 1770s. He argued that art beautified a gentleman’s country seat and conveyed to the owner a mysterious halo of superiority. ‘Is he rrright in zaying zis?’ Just for the heck of it I said, ‘Yes.’ ‘No,’ said Dr Wind. ‘You are abzolutely wrong.’ Art sprang from the innermost feelings of the unbound spontaneous liberation of the human spirit. Dr Wind was everything one wanted in a German professor: opinionated, and a firm disciplinarian.

I had been heavily reproved – and I brooded. Reynolds had tried to make the Brits love art. Why didn’t they love art anyway? Why in France and Italy does the picture fit the frame, the frame fits the room, the room fits the house, the house fits the square and the square fits the city and in England, it doesn’t? Art in England was as Reynolds described it: a sprinkling of sugar on top.

I began to think of art as an interior need. It wasn’t a question of an ornament or an expression of taste or a means to a reputation. You had to need it. This need was an interior craving that required no visible manifestation to make it real, though obviously a work of art ought to appear at some point, too. In Europe, art as a need was an essential component of several cultures. The same had not happened in England. The period from Henry VIII to Oliver Cromwell, so formative politically, had had the side-effect of destroying art as an integrated part of society.

I persisted nevertheless with Wind, and he took me under his wing. As my Finals approached, he said that he wanted me to take a doctorate and go to Moscow to study the works of Matisse in the Shchukin collection. I said thank you, but I want to paint. Ach, he said, looking puzzled. A week later he told his secretary, Well it will serve Stephen Spender right if his son does becomes a painter. It will be the judgement of heaven for that bad book he wrote on Botticelli. Wind’s secretary passed on his remark and I grinned. Wind was right. Dad’s book on Botticelli was bad.

I was doing fine with Dante, too. Dons gave me hints about my academic future. ‘This is the Keeper of Western Manuscripts. You’ll find he’ll come in useful when you go on to do research.’ I shook hands with a large lugubrious man and left the room as soon as possible. Panic was setting in. Did I want it, or didn’t I?

Via Dante, I came across the great Italian historian Gaetano Salvemini. His book on Florence in the late thirteenth century put forward a Marxist theory of class struggle that I thought was wrong. A second idea for a doctorate was that I’d go to Italy and research the Florentine archives to see if the guilds of the period could be described as ‘class’, in a Marxist sense. I suggested this to one of my tutors and he said Yes, this is a good subject for a PhD.

Whenever I talked about Marxism with my father, I said the problem was that I couldn’t think of people as being representatives of a class. He didn’t understand. Couldn’t I see that there was something called the Working Class, he asked? No, I said. I could meet a man in a pub and he might come from a different background from mine, but to me he would be just someone to talk to, or not, as the case might be. He would not be a ‘representative of the Working Class’. Dad thought this was very funny. Fancy that! Matthew can’t understand the meaning of Class War!

There was something awkward about this exchange. I suddenly thought: is he listening to me, or to a ‘representative of the Youth of Today’?

I ended my miserable Oxford career stuck in the library with books I loathed reading and no brain to make sense of them. But I was there, in the Upper Bodleian, and my father was disturbed by what he took to be my academic ambition. One day he asked Maro: ‘Is Matthew really going to become a Donny-wonny?’

Oxford is anti-creative. It wants to turn people into nice people not embarrassing boars [bores?] who do things. Scholarship is tolerated, because it shuts people up and prevents them being social nuisances: unless they are clever enough to be both scholarly and excellent after dinner conversationalists. But the arts when actually practised and not seen in museums are like muddy boots on the carpet. However, even they are allowed if you can convert them into social currency.

This isn’t a wild adolescent reproof of mine against my father. It’s a letter from Dad to me, giving what he thinks is supportive advice. He may have intended it to calm me down, but it was the exact opposite of the advice he’d given me when I’d started out at New College, which was that artists need to cultivate their brains. He’d have done better to say nothing at all. And part of my being at Oxford, so I thought, was to obtain the degree he’d failed to win himself. To please him! What was he doing casting doubt on the whole process?

My father’s Oxford career was in its way spectacularly successful, even though he went for a bicycle ride instead of taking his Finals and so failed to obtain any degree at all. He’d written and published the Marston poems, which many critics say are his finest achievement. He’d drafted two novels, though the first had to be abandoned and the second, The Temple, didn’t find a publisher for fifty years. As head of the Oxford English Society he’d been able to talk to many distinguished authors, who always seemed happy to come up to Oxford from London in order to meet the students. He’d published his first book of poems in a small edition, half of which was subscribed before publication by his friends, ‘most of whom got Firsts’, as he put it blandly in a letter to his grandmother. Above all, he’d made friends with Auden and Isherwood so that the three of them, if not exactly forming a gang, certainly added up to one of the strongest literary movements of the decade. All of which my father presented as ‘Don’t worry about Finals. I’ve never passed an exam in my life.’

As for failure, the clincher came decades later when he was stopped by a policeman driving his car around Trafalgar Square when drunk. He was asked to blow into the famous compromising balloon, but it failed to react. ‘I’m so sorry, officer,’ he said. ‘It’s just that I’ve never been able to pass a test.’

At some point during that autumn my father took me to one side and asked if he could dedicate a poem to me. It was called ‘The Generous Days’. I read it several times over a period of a week and rang him up to say No, I’d prefer it if he didn’t.

I disliked this poem, partly because I thought he was trying to send me a message in public of the kind that he would never dare to give me in private. The poem was about love, and I could glimpse Maro and myself in the background. But ‘Mindless of soul, so their two bodies meet.’ The couple in the poem wandered about, hopelessly kicking the leaves. And wasn’t there something masochistic in their relationship? ‘Soul fly up from body’s sacrifice, / Immolated in the summons.’ Also: ‘After, of course, will come a time not this / When he’ll be taken, stripped, strapped to a wheel.’ The ‘of course’ was especially offensive, because it seemed to take my fate for granted. I had no desire to be strapped to a wheel of daily life by my father, not even in a metaphor.

Deep down, I felt that Dad disapproved of my relationship with Maro because it was happy. At the time, I knew nothing about his comments to Reynolds Price on Rimbaud and the ‘derangement of the senses’. I just felt that he disapproved of happiness in the same way that he disapproved of academic studies, because both seemed to him complacent.

On my desk in front of me there’s the copy of The Temple which he gave us when the book finally came out in the Eighties. The dedication reads: ‘to Maro and Matthew, these youthful indiscretions, love dad’. I can’t help feeling there’s a gleeful note in there somewhere, a mild reproof.

The lease on St Andrew’s Mansions ran out and Maro began looking around for somewhere else to live. By chance, Sonia Orwell was leaving her old flat in Percy Street off the Tottenham Court Road in order to live in a house she’d bought in Kensington; so Maro took over from her.

Three rooms, a tiny kitchen, and a bathroom remarkably full of plumbing. One of the rooms was known as the ‘divorce’ room, because halves of estranged couples would squat there while their relationships irretrievably crumbled. Sonia was a good woman, but she loved taking sides in marital disputes.

We redecorated the whole flat in our usual double-quick time. The ‘divorce’ room was so small Maro could only paint gouaches in it. The living room had a wonderful Gorky in it, on loan from Mougouch. When I left Oxford, the bookshelves filled up with my academic books, plus a collection of old Horizons which we’d found in the attic that Sonia said we could keep.

This had been George Orwell’s last flat, though I don’t think he lived there long. It was also haunted. Several times Maro woke up and found a sandy-haired young man staring down at her. She said he had a very 1930-ish atmosphere. I never saw him.

Percy Street was within walking distance of the Slade, but Maro had finished her four years of study there. She began working in interior decoration. An early job was to decorate a bathtub for Ricky Huston, ex-wife of the film director John Huston (and mother of Anjelica). Ricky and Mougouch did gym together, writhing their elegant limbs on an antique kilim and swapping gossip about various friends they had in common. Painting that bathtub took Maro a long time. She was a quick worker, but Ricky thought the price she’d quoted was high in relation to the hours she’d spent on it, so she made Maro repaint it three times.

Opposite the British Museum, I discovered the communist book shop where Tony Hyndman used to hang out in the Thirties. I was fascinated by this shop. On a table in front of the entrance lay The Little Red Book we were supposed to wave on protest marches. Tucked away at the back were volumes by Mao Zedong on the tactics of guerrilla warfare, which were down to earth, and horrible. How to shoot class enemies. There was also a shelf of books by the victims of the Russian totalitarian state: Victor Serge and Ivanov-Razumnik. These were later overshadowed by the works of Solzhenitsyn, but even before his books came out, there was plenty of information on how badly things had gone wrong.

I wasn’t political. Just wishy-washy left-wing. It was the Kronstadt Rebellion that kept me from sympathizing with the Trots. The followers of Trotsky thought that if he’d taken power instead of Stalin, the revolution would never have gone bad, but it seemed to me that Trotsky had been perfectly capable of acting ruthlessly, because ruthlessness was part of the predicament.

I remember having a conversation about this with a friend after a party. We were both drunk. The question was: where is the morality in being communist? We both knew about the persecution of the kulaks and the Purges of the 1930s and both of us, therefore, hesitated in our left-wingery. Underneath a lamp-post, we talked it over. Surely there’s some moral high ground in communism?

He said: Everything to do with Russian history leaves one too dazed to form an opinion. For instance, one of the reasons why they won the war is because Stalin moved their heavy industries behind the Urals where the Germans couldn’t get at them. The cost of this operation was staggering. Thousands of people shot, incredible disruption pushed forward with brutality. He said that nobody in the West dared to argue that it was worth it, because it enabled Russia to win the war, even though it was probably true. ‘We just aren’t capable of calculating the morality of decisions made on such a scale.’

My Finals crept up with historical inevitability in June 1966.

During those dreadful eleven days, I kept clear of both Maro and my father, as neither of them believed in what I was doing. Instead, I phoned my mother each evening and she steered me through. She knew about performing on a particular hour of a particular day.

And six weeks later, my Viva came and went in a flash. I was asked to define the English Gentleman, as I’d said something iffy on that subject. The result was a decent Second, with a touch of alpha in four papers and gammas in three others. You can’t really be an academic with a gamma double-minus in the background, so whatever temptation there was, withdrew.

Maro and I spent that summer in Majorca, where I started painting again.

I wrote to my father saying that I was trying to unlearn the habit of thinking in words. It was similar to something he’d said before my Finals: ‘Maybe you will be able to shed some of Oxford in the next two years.’ But he’d also said that artists in England were stupid. ‘The great ones of course are clever and don’t need educating much, but the majority even of quite good ones are such inchoate oafs.’

I must have written him a letter saying I wanted to join the oafs. In midsummer he wrote back, to both of us: ‘When Matthew writes about having to learn not to think I see what he means but wonder whether he is right. Obviously a painter has to work from his senses and a certain kind of thinking is bad for this. On the other hand the idea that a painter has to be a dumb instinctive animal seems very Anglo-American and accounts for the limitations of Anglo-American painting … Painters don’t think enough. Nowadays the best of them seem to have one-track minds, which make them arrive at a formula – Motherwell, Rothko, Rauschenberg and even Francis Bacon – and then they stick to this out of an inability to think of anything else.’ There was one exception: Picasso. ‘The point is to be one thing one doesn’t have to jettison one’s other gifts. One somehow has to do the one thing out of the development of all of them.’

Just as I was wondering what to reply, he sent us a crushing letter written from a hotel halfway up France. We’d been planning to visit them, but Majorca to Arles wasn’t an easy journey and I must have asked him for some money. ‘Even if you don’t feel things you might consider other people to the extent of trying to enter into, imagine their reactions. Not to do so is just embarrassing, like Melvin Lasky.’

Dad’s harsh letter was the result of three stresses. We’d delayed telling them what our plans were, and ‘what are your plans’ figured highly in my mother’s sense of order. Then André Malraux had invited him to Paris, and he wanted to go, and so did Mum (because she wanted Malraux to force the phone company to give her a telephone, which he did). If we’d told them earlier that we were coming, Dad might have cancelled Malraux: but on the other hand, maybe not. (The argument was hard to follow.) Last but not least, an article had just appeared in Time magazine about the machinations of Encounter.

Even at this late date, my father tried to laugh it off. He wrote to Nikos that the article ‘enraged Natasha so much (partly because I treated it as a joke) that it was really quite appalling. In a funny way I don’t think we’ll ever quite recover.’ Lasky was involved, and my mother honed in on him as the root of the evil. But Stephen wasn’t about to assign all the blame to him. He added mildly, ‘Lasky does seem to have this gift for making the wives of his colleagues hate him, while his colleagues merely despise him.’

I arranged for Maro and me to sail back to England as the crew of a tiny yacht. There was room for just the three people: us two, plus the skipper who at least knew how to sail. I looked at this lopsided sloop tucked away in the harbour and thought, With any luck we’ll be drowned, so I won’t have to face any more of this.