WE DIDN’T DROWN as we sailed across the Bay of Biscay, but the trip was grotesquely uncomfortable. There was a leak in the exhaust of the diesel engine and the yacht staggered along, full of fumes. I must have vomited on every nautical mile of the sea between Vigo Bay and Portsmouth, spattering on the heaving asphalt of the Atlantic confetti-like fragments of my insides. Good. It had the effect of placing a full stop, new chapter, underneath my Oxford days.

I found a studio on the top floor of a house in Holloway near the Nag’s Head. The building was owned by a racketeer who couldn’t evict his tenants and the place was a mess. Underneath me, a veteran of the First World War thought I was dropping grenades on him every time I walked across the room. Underneath him lived a bus-driver with a young wife and baby daughter. As Mr Puttock, the war veteran, was off his head, I made friends with the wife and baby, especially the baby. I made a portrait of her. It was a fat baby on a fat pillow, pink on pink.

In my attic, I went back to the former themes of New College: rooftops, slabs of meat and self-portraits. I hated what I was doing and my head was full of words. I’d paint for an hour and then have an interesting thought about Titian or Frans Hals; stop to write it down, then tear it up impatiently, as ‘words on paper’ was not the medium I wanted to create in.

Walking back from a pub one day, I heard a voice in my head say, ‘And he was using up his pencils at the rate of one a week.’ Where did this voice come from and whose was it? It was ridiculous to claim that using up one pencil per week meant anything, for what ‘he’ was drawing might be completely worthless. But who was ‘he’? Well, obviously, ‘he’ was me.

I protested. But I don’t want a ‘he’ in my head pretending to be me. It’s crazy. And there are too many people up in my head anyway – the ultimate attic, far above Mr Puttock who can’t forget the trenches. Twenty-two years old, free of education, free of exams, out in the big wide world, no problems with my love life, yet here a worm-like voice still dug its way through the churned suburban burden of my mind.

I decided: this voice isn’t mine. It’s my father’s.

Through the clutter of trying to make decisions about my life shone this interior commentator I’d inherited from him, from Stephen. For it was Stephen Spender, the poet with the alliterative name, who carried with him the eternal commentator, the divine recording angel of his own success. Wasn’t ‘success’ behind ‘him’? Yes, because otherwise the commentator wouldn’t have been impressed – and he shouldn’t be impressed – by the fact that I was using up one pencil every week.

In June 1966, Nikos Stangos met David Plante, a young American writer who’d recently arrived in London. They became lovers, and after a week Nikos invited David to come and live with him. Even though the gesture was generous, Nikos warned David not to come too close; or, as David wrote in his diary, ‘I must not think that this meant I should feel I had to return the feelings Nikos had for me.’

Stephen at this point was an absent ‘older Englishman’, who’d have to be told about the new relationship when he came back to London. Luckily, when they all met a few weeks later, Stephen was thrilled. For him it solved an increasingly difficult situation. The tendency of Nikos to reject any compliment, however mild, had begun to exasperate Stephen to the point where he thought he’d have to bring the relationship to an end.

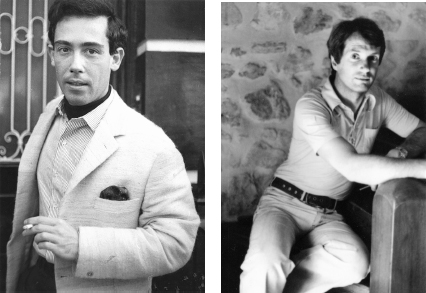

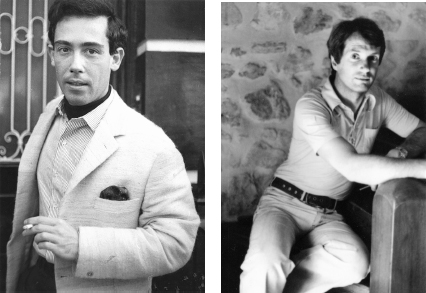

Nikos Stangos and David Plante.

Nikos didn’t want to be tied down. When he complained about his rooms and wondered if he shouldn’t redecorate them, Stephen said he liked them as they were; but even this was a risky thing to say. ‘I suddenly realized the reason is that I had never seen your rooms apart from you. They are, in my mind, irradiated by you, and somehow miraculous. Probably you’ll consider this subtly insulting and write an angry protest.’

As the memory of that first weekend in September began to fade, Stephen turned to trying to help Nikos find his way as a writer, both with advice concerning the writing itself and with recommendations to various people for jobs. At one point he wanted Nikos to help him turn his inaugural lecture at the Library of Congress into a book. They’d split the profits, fifty–fifty. He accepted a poem by Nikos for Encounter, then hesitated, partly because Frank Kermode was now in charge of the literary side of the magazine, partly because he could not be sure that the poem would ever come out, given Lasky’s delaying tactics. Finally, after about a year, Stephen agreed to revise some translations of Cavafy that Nikos had started years before. These were eventually published in a special edition, with illustrations by David Hockney.

Two weeks after David arrived in London, Stephen was sent by Natasha to plant some trees in her garden in Provence. She was swotting for her exams and couldn’t go herself. At Nikos’ suggestion, Stephen took David with him. Nikos evidently thought this was the quickest way of integrating David into the relationship that he’d awkwardly shared with Stephen: or maybe he thought David could become a part of it.

On the train to Paris, Stephen caught sight of Francis Bacon, about to attend an important exhibition of his work at the Galerie Maeght. They joined forces, and for a few days David was introduced to a glamorous side of English and French life that hitherto he’d never even imagined. Mary McCarthy, Philippe de Rothschild, Louis Aragon. Jokes were made about having to plant plants with Plante. And when Stephen and David continued down to the South of France to plant those trees, Francis Bacon came with them.

David had not yet met Natasha. Indeed, for several months an elaborate charade was performed by Stephen as to when she should be told, how she should be told, and whether or not she would be upset when finally she was told. David formed the impression that Stephen wanted ‘to keep Natasha alerted to his sexuality without admitting it to her, to make her wonder’. It isn’t correct, for my mother of course was acutely aware of my father’s sexuality, but it was a nice game to play within the world of men-against-women. It continued for some time. When finally Nikos and David had lunch with Natasha at Loudoun Road, they had to pretend they’d never been to the house before.

Years later, my mother integrated the tree-planting episode into a book about her garden in Provence. And retrospectively, she took charge of the whole thing. ‘I had managed to design the walk on a large roll of cartridge paper, and Stephen took a holiday break between books and went with Francis Bacon and David Plante to translate my plan into action.’ And they’d all had an improving time down there. ‘Stephen’s autumn expedition had been felt by all three friends to be not only a horticultural adventure but also a golden interlude of inspiration with which Provence endowed them. While Francis was wandering the sites of Van Gogh’s years of painting in Arles and Saint-Rémy, Stephen and David applied themselves to deciphering and fulfilling my plan.’

She hadn’t met David at that point, and there’s no mention that Bacon was in Paris for the opening of his show at Maeght. It’s hard to imagine a man like Francis Bacon going in for ‘a golden interlude of inspiration’, let alone a ‘horticultural adventure’. Her version underlines the tenacity with which my mother controlled the marriage that she, even more than my father, had created. However hurt she was by the dramas that resulted from my father’s insistence on his ‘freedom’, she always managed to present everything as if it had happened on purpose, with the noblest of motives and completely under her control. Once she’d invented such an interpretation, she firmly believed that the past had actually happened that way.

It may have seemed a slight step from Stephen loving Nikos to Stephen supporting Nikos and David as a couple, but it was huge. The first relationship was individual, with elements of secrecy, the second was shared and in the full light of day. My father needed to be in love, because he always hoped that it would bring him the feelings that could be turned into a poem. In greeting Nikos and David as a couple, however, Stephen was saying goodbye to intimacy and substituting for it social recognition. Love was poetry, social recognition was politics.

Stephen told David: ‘I wish that when I was your age I had had what you have now with Nikos.’ David replied, ‘But Stephen, you are giving us both what you didn’t have at our age.’ This was true. By treating him and Nikos as a couple, Stephen helped them to become a couple. ‘I feel he has given Nikos and me a world in which our relationship can expand and expand, so that in discovering the world he has opened to us we are discovering one another.’

There remained the vicarious fantasy of young men all together, facing the world in order to conquer it. And within the confines of this fantasy, Stephen could remain the same age he’d always been: a boy of seventeen, ‘without guilt’.

Nineteen-sixty-six was the year when the Encounter scandal finally broke.

In May, my father was still in America teaching at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. In his absence, Maro and I were heavily involved in keeping my mother calm in the face of Lasky’s perfidy. As my father put it in a letter to Nikos, ‘Natasha is hysterical on the subject of Lasky & Encounter and the children are having hell trying to cope with her rage.’

A fortnight or so before he arrived back in London, Maro and I invited Mum to supper at Percy Street. After supper the three of us sat down to summon a spirit through the Ouija board. We thought it would be a distraction for her. Mum addressed the room in a serious voice: ‘Who is behind the financing of Encounter?’

The upturned glass started moving, slowly at first, then faster. I looked at Maro, and her eyes were jumping to the appropriate letter a fraction of a second before we got there. The Ouija board told us, ‘Malcolm Muggeridge.’

Afterwards, when we were alone, Maro hotly denied that she’d cheated. But we knew the name of Muggeridge was in the forefront of Natasha’s suspicions. He’d worked in British Intelligence during the war and had kept up his contacts ever since. Years later, it turned out that Mum’s suspicions had been justified.

I’ve probably given too much weight in this book to the Encounter affair in relation to other aspects of my father’s life: for example, his genuine and generous concern for young writers, his intuitive understanding of art, his great capacity for producing unusual books of criticism and his own considerable achievement as a poet. But he’d also aimed at editing a magazine for at least ten years before Encounter materialized, so I cannot argue that it was an accidental distraction. Life did not impose this task on him. He’d sought it. Thus Encounter, for me, stands for the parts of my father’s life that are the real enemies of literary promise: the contamination of art by power, the ambiguous role of the intellectual in society and the political relationship of England with the United States. Encounter in my mind stands for Temptation.

I need answers to the following questions: Was he aware of what he was doing? In what way did Encounter represent the CIA? And how did my father manage to emerge relatively unharmed, whereas most of the others who had been involved with the Congress for Cultural Freedom were tainted for the rest of their lives?

First, a quick run through the facts.

On 27 April 1966, the New York Times published an article discussing American support of anti-communist liberal organizations, such as the Congress for Cultural Freedom and its magazine, Encounter. The next day Arthur Schlesinger, in a TV interview with the left-wing scholar and politician Conor Cruise O’Brien, admitted that support of the non-communist left was a part of American foreign policy. Five days later, Stephen wrote to Mike Josselson asking whether the Congress for Cultural Freedom was a CIA front organization. This letter was not answered, but it seems that it was read and discussed in the CIA headquarters at Langley, Virginia.

In the background of these events lay President Johnson’s irritation with those Democrat left-wingers who were coming out against the war in Vietnam. His anger at what he saw as their betrayal was swiftly becoming paranoid. The previous June, he’d told one of his assistants: ‘I am not going to have anything more to do with the liberals. They won’t have anything to do with me. They all just follow the communist line – liberals, intellectuals, communists. They’re all the same … I’m not going in the liberal direction. There’s no future with them. They’re just out to get me. Always have been.’ So it’s possible that the whole ‘international non-communist left’ was dumped as a result of a peremptory order from President Johnson.

On 19 May, Conor Cruise O’Brien read a lecture at New York University suggesting that Encounter was part of the ‘power structure’ of Washington. (A personal dig, seeing that Stephen, while working at the Library of Congress, had recently been living in Washington.) O’Brien’s piece was immediately published in Book Week and distributed by the US branch of the PEN Club. In response Goronwy Rees, for the August number of Encounter, wrote an attack on O’Brien. Over the summer, O’Brien wanted to publish a reply in the New Statesman, but Frank Kermode persuaded the editor not to print it.

For a while things hung fire. In the background Spender and Kermode tried frequently and unsuccessfully to obtain a straight answer about the CIA background. From September to October, Stephen was in India on behalf of UNESCO. In January 1967, he took up a teaching job at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. Then in February, O’Brien sued Encounter for libel contained in the personal attack by Rees, cleverly choosing to present his case in Ireland, where he was something of a hero. Encounter lost. Which implied that his thesis, that Encounter was subsidized by the CIA, was true.

From then on the situation deteriorated. At Wesleyan, Stephen was contacted by Ramparts magazine saying they were about to reveal the connection between the CIA and Encounter, and what did he think about that?

Ramparts was more interested in the CIA’s use of infiltrators within the international students’ unions. Having read this in a newspaper report, and not noticing the implications regarding Encounter, I wrote to Dad asking whether infiltrating student unions with secret agents constituted Fascism.

Out to dinner that evening at Wesleyan, my father put this question to an ‘Admiral type’ who happened to be sitting next to him. ‘The effect was electrifying. He shot about 2 feet into the air and said: “I’d have you know I’m the greatest friend of Allen Dulles (head of the CIA) and we planned this thing together. Tell your son, that it is like your BBC or British Council. You Europeans will never understand how we Americans do things.”’

I’m thrilled my letter produced this indirect confirmation that there was a difference between Britain and the United States when it came to fighting communism. But to go on with my father’s letter:

America is not a fascist country. It is much more complicated than that. A thing like the CIA affair is more like the conspiracies of big business than like the police state. It is really more a form of cornering a market, the commodity cornered being power rather than money, though lots of money made it possible. Paradoxically it arose originally as a move by Central Intelligence to get round McCarthyism. In 1949 the great Foundations had not got going properly, and all arrangements for travel, culture etc were subject to attack by the UnAmerican Activities Committee for being Red. This meant in practice that the fare of a student to an international conference could not be openly paid unless the student was approved by McCarthy or not likely to be attacked by him. So some rather bright and even liberal people in Central Intelligence used secret funds to sponsor indirectly through respectable seeming channels (like the Congress for Cultural Freedom, the Asian Foundation etc) people who presented a ‘liberal’ though anti-communist image of America. The people, of course, were not told about this and mixed among them were CIA agents and very skilful amoral operators gifted in deviousness concealment and not so much lying as never telling the truth, of whom a prime example is Melvin Lasky. Above all these operators have a limpet-like tenacity and once they have got into a position it is almost impossible to remove them, because you can never obtain evidence to prove they are agents because the Intelligence agencies are the only people who could supply the proofs.

For the first time my father heard that the man in charge was Cord Meyer. Again, coincidence gave him clues. A colleague of his at Wesleyan happened to be Richard Goodwin, a former adviser to both Kennedy and Johnson. In his letter Dad writes: ‘I asked him the other day “Who is Cord Meyer?” He said: “He’s one of the top CIA directors, responsible for culture.” I said: “He seems to have played quite a role in my life the past twelve years.” Dick Goodwin said: “Don’t I know it!”’

Back in London, a new British representative was appointed to the board of Encounter: William Hayter, the Principal of New College (where I met him several times), a former ambassador to the Soviet Union with experience in secret matters.

Everyone wanted to damp down the scandal. Nobody wanted Spender to leave and start writing articles criticizing the way Encounter had been managed over the last decade. By this time it was widely suspected that Lasky was employed by the CIA. I remember Stuart Hampshire telling my mother, ‘He’s a blown agent,’ which immersed the matter into the murky world of spy stories. In London it was taken for granted that Lasky would resign and Encounter would return to what it was supposed to be: an English magazine run by English editors. But Lasky was a fighter and he refused to give in.

At this point the difference between Spender and Kermode on one side and Lasky on the other becomes clear. Lasky was a Cold Warrior. They were intellectuals. They believed in telling the truth, he was prepared to do whatever he felt was necessary to win. If they assumed that having been publicly unmasked, he would withdraw in confusion, they were mistaken.

Lasky had Cecil King, the newspaper magnate, on his side. King had ostensibly taken over the financing of Encounter from the CCF in 1963, when questions about the CIA had first been aired. He hadn’t interfered in the running of the magazine; nor (it seems) had he looked at its accounts. He was the perfect owner.

King’s political agenda was as tough as Lasky’s, and he preferred Lasky to Spender as Encounter’s editor. At a later date, King was involved in a bizarre plot to overturn the Labour Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, in a coup d’état. (King thought that Wilson was a Russian spy. He tried to replace him with an emergency government headed by Lord Mountbatten.) Since King owned Encounter, there wasn’t much to be done. There was, however, an Encounter Trust that oversaw the running of the magazine. A meeting was scheduled for 20 April 1966, so that King and the Trust could come to an agreement.

Arthur Schlesinger flew to London for this meeting.

My father had arrived back from Wesleyan the day before. Even at this late date he could still feel bored by the whole thing. As he wrote to Nikos, ‘The trouble with this Encounter row is it is all about trivial things to do with quite trivial people – and yet at the same time it has to be fought.’

Egged on by my mother, the first thing he did on arrival was to telephone Malcolm Muggeridge. Hadn’t Malcolm always told him that the money for Encounter came from private donors with impeccable credentials? According to my mother, Malcolm told my father: ‘So I did, dear boy, so I did. But I wouldn’t bet your bottom dollar that’s where it really came from.’

Next day, Maro and I were invited to Loudoun Road for supper, during which Schlesinger was supposed to be won over to Stephen’s side.

We arrived early. Dad opened the door. He was tense and jet-lagged. Along with everything else, he’d lost his voice. He hissed at us in the front hall, ‘Whatever else you do, be polite. Everyone says Arthur’s going to be the next Secretary of State.’

When Schlesinger arrived, we were left alone with him in the piano room. Mum was downstairs cooking, Dad was so nervous he stayed in his study. He was probably thinking that Arthur must have known about Encounter’s financing from the very beginning. How would he get through the evening without betraying his anger?

In the piano room we were polite to Schlesinger as requested, but we were not over-awed by the future Secretary of State, because Maro had a family connection with him. Schlesinger, like several other members of the East Coast liberal left, was a regular summer visitor on Cape Cod. Mary McCarthy and her then husband Boden Broadwater also summered on the Cape, her former husband Edmund Wilson lived in Wellfleet, Dwight and Nancy Macdonald had been there for years. Some of the properties owned by members of this group had been sold to them by Jack Phillips, Maro’s ex-stepfather. There were Slough Pond and Horseleech Pond and Slag Pond – lots of pond life among those drab, moth-eaten pines. And cocktail parties. Maro as a child had often passed the literary peanuts on several distinguished lawns. One evening, instead of passing the peanuts, with her Phillips half-sisters she’d gathered up baskets of frogs and thrown them at the feet of the grown-ups.

So Arthur knew Maro from Cape Cod, and for a while we talked about that. Then, of all things, the subject of the Marx Brothers came up. Arthur gave us a seminar on their movies: the early ones with a muted social context and the later ones that gradually reached total anarchy. Their hatred of war, for example. He said the Marx Brothers came from a tradition of Jewish radical socialism that went right back to the Russia of the 1880s.

Dad still did not appear. Finally I asked Schlesinger: could he please tell us something about the CIA and Encounter? He was embarrassed, but the explanation that followed had the same friendly but didactic tone with which he’d just compared Groucho’s political rage with Harpo’s gentler one. And it corroborated what my father had just told me in his letter. The CIA, he said, is a large institution employing many people. Most of the personnel come from the military. It’s divided into sections that are often in competition with each another. The group in charge of ideas – and we wouldn’t deny that Encounter was an ‘ideas’ proposition – is extremely small and beleaguered and despised by everyone else. The military prefers to support right-wing governments, in Europe and elsewhere, because direct confrontation is instinctive to them. They distrust the subtle, long-term calculation of using the centre-left to win over votes from the communists. In spite of this, the CIA is the only American institution that could ever have supported such a plan. ‘You’d never have convinced Congress to back anything that had the word “socialist” in it,’ he said. ‘For a liberal magazine like Encounter to exist at all, it’s almost a miracle.’

My main reaction at the time was disgust that my father, an English poet, should have become a cog in machinery so complicated, and so utterly bound up with the United States.

I don’t remember what happened at supper, but afterwards Maro and I drove Arthur back to Claridge’s Hotel in my cramped Morris Minor. It was raining. There was more talk about Cape Cod as the windscreen steamed up and we felt our way towards Mayfair. (What was Mougouch up to now? Does she like living in London?) We got out of the car to say goodbye and stood under the hotel’s wet awning. Arthur said we shouldn’t worry about Stephen. All this would blow over. It wouldn’t affect him. ‘He’ll survive.’

As for the Encounter crisis, it was hardly worth having crossed the Atlantic for. ‘It’s really not that important.’ Then, feeling that our silence was not entirely on his side, he added defensively, ‘Except of course people’s feelings are always important.’

My father went back to Wesleyan without attending a second meeting of the Trust on 5 May. At this meeting Cecil King made it clear that he supported Lasky. On 7 May, Kermode and Spender resigned as editors, and on the following day Stephen gave an interview with the New York Times stating his position, which was that he could not continue to work as an editor of a magazine that had been financed by the CIA.

The Trustees thought they’d also better resign, and they did so as quietly as they could so that Encounter could survive. Spender, threatened by Lasky, resigned from the Trust on 11 May. Lasky had told him he’d tell the press that, as Stephen had been Chairman of the British CCF back in the early days, he must know more about the financing of the Congress than Lasky did!

On 20 May, the Saturday Evening Post published an article by Tom Braden, one of the founders of the ‘non-communist left’ strategy. He was proud that the CIA had been immoral, he wrote. This is taken by scholars as the moment when the CIA washed its hands of a discarded policy. Braden would never have published his piece without the CIA’s approval.

Now to the three questions that interest me. Did my father know? Was Encounter run from Langley? How did his reputation survive?

With regard to the first question, let me play the devil’s advocate and summarize the case against him. He’d wanted to edit a magazine from the late Thirties onwards, and he’d become the co-editor of Horizon at the beginning of the war. Towards the end of the war, he’d worked for the Political Information Department, which was the public face of the Political Warfare Executive, in charge of all propaganda directed at Europe. In 1945, he’d wanted to start an Anglo-German magazine with Ernst Robert Curtius. In 1946, he’d been asked by Information Services Control to provide a plan for an international magazine, and he’d done so, complete with the suggestion that the British government should pay for it. Meanwhile the bureaucratic successor of the Political Information Department was the Information Research Department, the subsequent British backer of Encounter. While it lasted, he was Chairman of the British Committee for Cultural Freedom. He made numerous trips outside England on behalf of the Paris CCF, the British Council, the International PEN Club, UNESCO, the BBC and occasionally, in a very nebulous way, the Foreign Office. (I am guessing that his contacts with Guy Burgess had some FO connotations.) On the other hand, he was never an employee of the British Civil Service, and he never signed the Official Secrets Act. His engagement by the above bodies was always fee-earning, which meant he could accept a task or not, as he felt like it.

I am sure that most readers of this book will say: It’s impossible that he did not know what he was doing. That he didn’t depends on understanding the power of his ‘ambivalence’. Whether vice or virtue, my father’s ‘ambivalence’ kept him open where to others the choice would seem either/or. ‘Ambivalence’ in fact means not choosing, not selecting, not dismissing new experiences, not concluding, not – and I cannot stress this strongly enough – being pinned down.

Stephen always claimed that he never knew about the CIA connection and that from 1962 until 1966 he had been consistently deceived by his employers. His anger was sincere, but righteous anger of an uncontrollable kind often overcame him whenever his ‘innocence’ was placed in doubt. For example: his anger with the political commissars during the Spanish Civil War when they didn’t see why they should release Tony Hyndman from his duties, or his anger with Inez when she’d left him after she decided she couldn’t accept his continued relationship with Tony.

The mere fact that he was sincerely angry does not convince me of his innocence. Yet one aspect does strike me as curious. Whenever he writes to his friends or in his journal about Irving Kristol, or Dwight Macdonald, but most of all Melvin Lasky, politics do not feature in his complaints. He held against them their hatred of literature, their self-serving manner and, in Lasky’s case, the habit of lying to cover his tracks. He thinks that the ruthlessness of Lasky, like that of Michael Goodwin before him, is due to their pursuit of personal ‘success’, not that they were working to a secret agenda. He gives no hint that he himself was involved with power, influence, propaganda or cultural manipulation, or that he was aware that his colleagues were.

Against this plea for his innocence there is one small incident.

David Plante tells me that twenty years later, in the period of Gorbachev’s glasnost, he and Nikos invited Stephen to tea to meet a young Russian friend of theirs, Sergei Belov, recently arrived from Moscow. The subject of Encounter came up. ‘The whole story had been prominent in the Soviet news; blinking, as if wondering if he should speak or not and finally giving way to the presence of this young Russian, Stephen said, “I knew, somehow I knew,” and we were all then silent.’

David comments: ‘He knew, but only “somehow”, and don’t you think that this “somehow” was a constant helpless doubt he had about everything he did, “somehow” never sure of anything?’ No, I don’t believe he was unsure about what he did, though it’s a plausible argument. On the contrary, within the cloud of ambivalence that surrounded him, Stephen was remarkably persistent in pushing forward his ideas over a long period of time. In that respect, to admit to a Russian what he’d never admitted to anyone else seems to me significant, because there was a Russian side to the whole story that did not die when my father left Encounter.

My verdict: he did not know about the IRD, or the CIA’s financial involvement, or the serpentine chain of command going back to Cord Meyer. But he knew what Encounter was for, even though his for was absolutely not the same as Mel Lasky’s.

I often thought of saying to my father, ‘Dad, you think you’re a poet but in fact you’re a politician, and a brilliant one,’ but I never did.

Auden wrote a tolerant and understanding letter to my mother when she wrote to ask for his help against Lasky’s attempt to subvert Stephen’s reputation. ‘You and I may think he has been a little naïf, and even, perhaps, once he had got Encounter really on its feet, a little negligent. But his artistic, political and financial integrity are so obvious that I can’t imagine what they could possibly accuse him of.’

With regard to the second question, how much propaganda was involved in Encounter, much work has been done by specialist scholars and more still remains to be done.

From 1954, the man in charge was Cord Meyer, who within the CIA occupied a precarious position. He’d once been investigated by the FBI for ‘communist tendencies’, and it took him a year to clear his name. This corroborates Arthur Schlesinger’s impression that the cultural department of the CIA was a beleaguered minority, with rival departments constantly intriguing against it. The chain of command travelled from Cord Meyer to Mike Josselson to Melvin Lasky – all under the strain of having to keep things secret. Plus, in the background, the British IRD, which constantly resisted any attempt by the CIA to move ‘their’ magazines towards overt propaganda.

In my opinion, the chain of command was too convoluted for the story of Encounter to be interpreted as a successful CIA plot. Money passed hands. Nothing more. No instructions.

This assessment does not alter the fact that, if you are a writer who has been selected because you represent an undisclosed government programme, your writing is loaded with messages that you didn’t intend. It’s one thing if a ballerina dances because she’s ambitious and loves dancing, and entirely another if she’s been chosen without her knowledge to represent the West’s idea of political freedom.

Meanwhile my father’s participation in Encounter reveals many differences between England and America regarding how the Soviet bloc should be confronted, and the ways in which their respective intelligence services fitted into society. In my view these aspects have not been sufficiently discussed – but at this point I have to give way to feelings that cannot be so detached. The fact is, I absolutely loathe the mixing of politics and culture. Although I think I’ve managed to create a life that is generally free from stress, on this subject I am unable to think coherently.

I know that there have been periods when art has been used politically, and that sometimes the results are marvellous. The baroque churches of the Counter-Reformation, for instance. And what about the Parthenon? And the great paintings that Jacques-Louis David dedicated to Napoleon? I even like moments when political rhetoric goes mad, such as in the portrait busts of late Roman emperors, when the vulgarity of different coloured stones unconsciously mocks the nobility of their demeanour. But all such cases involve the transparent use of art. It’s politics by visual means, and we can judge it accordingly. With CIA involvement, the US covert programme mocks the art it’s designed to support.

In the 1970s, articles were written to suggest that the American Abstract Expressionist movement was a vast CIA plot. To put it briefly: Jackson Pollock was pushed to the front because his manner of painting epitomized the freedom of the West. And it was a success. The Soviet East was unable to offer a counter-offensive. Italian painters such as Afro, Scialoja and Vedova abandoned Social Realism to follow the lead of the Abstract Expressionists, and the Italian Communist Party embraced them, thereby moving Italian culture into a fluid role somewhere between America and Russia. Social Realism was so out of fashion by the Seventies that figurative painters had a hard time finding exhibition space.

Some left-wing critics viewed this American influence on Italian art with misgiving, and the idea that it might all be a CIA plot went straight to the heart of conspiracy theorists. And, inevitably, one day I came across an article that mentioned Maro’s father and my father in the same breath as tools of American imperialism. This dark thought had lurked in the back of my mind for a long time, but I was unprepared for my own reaction when it appeared in the press. I was overwhelmed by physical revulsion. It was a ‘short circuit’ between my father and Maro’s of the worst possible kind.

I should have recovered by now but I don’t think I have. The fact that our fathers were involved means that, for me, this particular punch goes way below the belt.

Third question: how did my father emerge unscathed?

When Arthur Schlesinger told Maro and me under the awning of Claridge’s, Your father will survive, I was irritated because I assumed that of course he’d survive. What was he talking about? But it was a good point. Mike Josselson and Nicky Nabokov saw their lives damaged by exposure. ‘Your father is still famous,’ Josselson’s daughter told me recently, ‘my father is just slightly infamous.’ Stephen was saved by the fact that Encounter was only one part of a complex life. ‘Ambivalence’ also meant being interested in more things than Encounter.

Stephen never held it against Nabokov that he’d been involved in the deception. On the contrary, he felt sorry for him. Far in the future, when Nicky was long dead, a rumour surfaced that he’d been paid half a million dollars for not writing his memoirs about the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Because he did not care about money, my father thought this was merely amusing; but my mother, who was as careful as Dad was frivolous when it came to money, felt that the person who ought to have been paid a fat sum was Stephen, not Nicky. As the editor of Encounter, Stephen had been far more influential. And he’d also been the Agency’s dupe.

Stephen took for granted that he’d succeeded in keeping his political life separate from his creative life. Literary London accepted this, as it accepted with unexpected calm the revelation of yet more American interference in English politics. It was only to be expected. ‘Too much politics’ was not the accusation levelled against my father by literary London in his later years. Critics attacked him because he’d been too ‘social’; and the idea that to his peers he’d become a ‘parlour poet’ hurt him deeply. The sense of failure that often came over him in his old age had more to do with wasted time and a feeling that he had not used his gifts properly. The novels he’d written didn’t really work and too many poems had failed to materialize because he’d been busy with other things. He tried not to let his sense of failure, which was sometimes strong, overwhelm him. My father was, after all, an optimistic man.