FIGURE 1. Birth certificate. (Courtesy of The Albert Einstein Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel)

The Personal and Family Spheres

FIGURE 1. Birth certificate. (Courtesy of The Albert Einstein Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel)

Vital Information: Certificates in Facsimile

Below we present samples of important extant facsimile documents relating to Einstein’s life. Translations or further information can be found in the cited cross-references.

Fig. 1. Birth Certificate. See also Birth Information and Family, p. 9

Fig. 2. School Report Card. See also Education and Schools Attended, pp. 28–30

FIGURE 2. School report card. (Courtesy of The Albert Einstein Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel)

Fig. 3. Doctoral Certificate. See also Part II, Doctoral Dissertation

FIGURE 3. Doctoral certificate. (Courtesy of The Albert Einstein Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel)

Fig. 4. Nobel Prize Certificate. See also Part II, Nobel Prize

FIGURE 4. Nobel Prize certificate. (Courtesy of The Albert Einstein Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel)

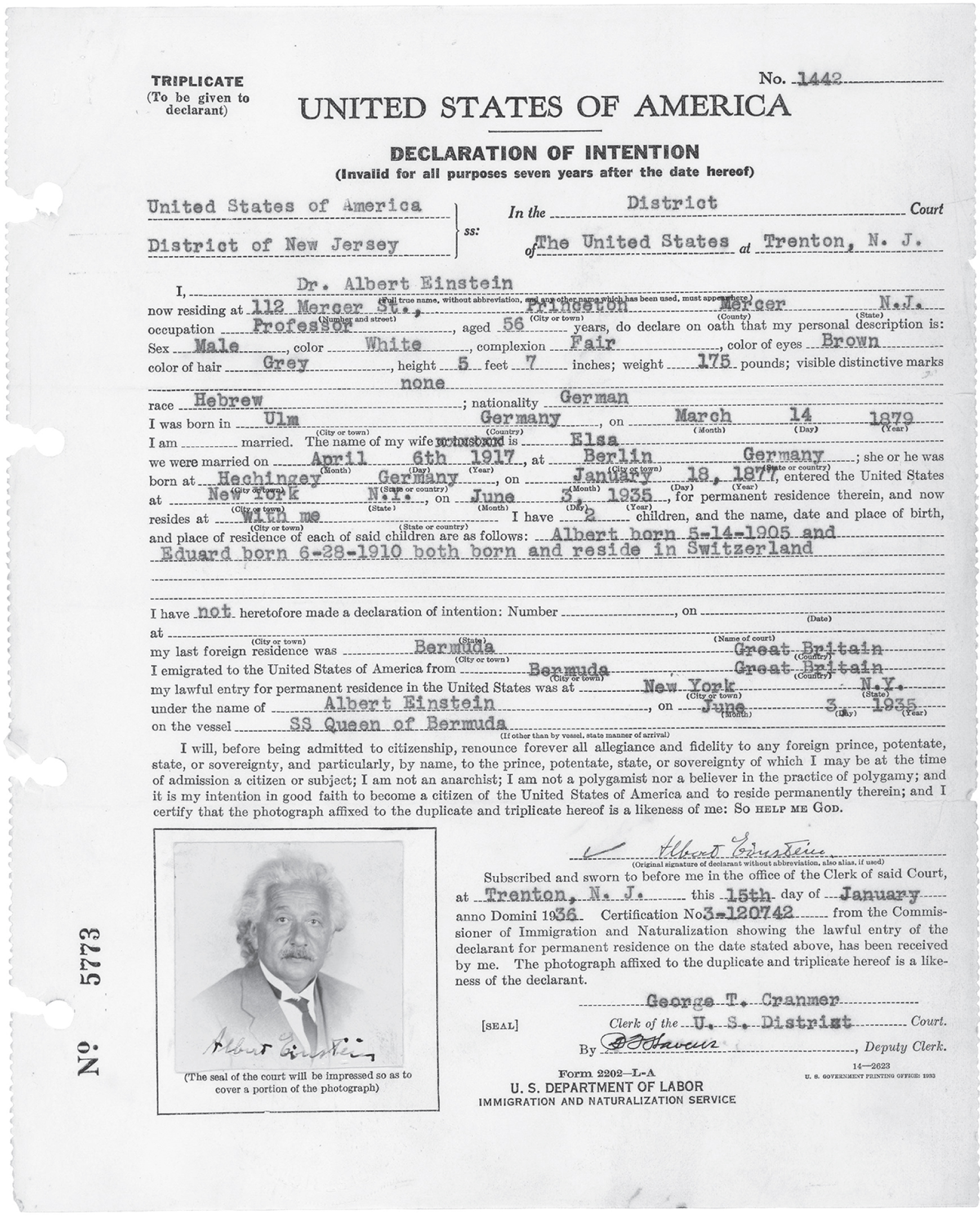

Fig. 5. U.S. Naturalization Certificate. See also Citizenships and Immigration to the United States, pp. 22–26

FIGURE 5. U.S. Naturalization certificate. (Courtesy of The Albert Einstein Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel)

Fig. 6. Death Certificate. See also Death, pp. 122–132

FIGURE 6. Death certificate. (Courtesy Mercer County Courts)

Birth Information

(As given on Birth Certificate, fig. 1, pp. 2–3)

Date of Birth: March 14, 1879, at 11:30 in the morning, a male child, first name of Albert

Place of Birth: Parents’ apartment, Bahnhofstrasse B, No. 135, Ulm, Württemberg [Germany]

Parents: Pauline née Koch, a homemaker; Hermann Einstein, a merchant

Parents’ Religion: Jewish

Signed by: Hermann Einstein

(See also Einstein Papers Project and The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, below)

When, in March 1933, Einstein did not return to Germany after the Nazis came to power, his stepdaughter Ilse, with the help of her husband, Rudolf Kayser, and her sister, Margot, packed up his papers in the Berlin residence along with some furniture and other belongings. Rudolf also bundled together some papers at the Einsteins’ summer home in Caputh. Through connections with the French ambassador to Germany, André François-Poncet, the Kaysers were able to remove these portions of Einstein’s literary estate to France via sealed diplomatic pouch. From there they were shipped to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where Einstein took up residence in autumn 1933 (see Fölsing, Albert Einstein, p. 666). These papers and files constituted the earliest form of what later became the Einstein Archives.

In accord with Einstein’s Last Will and Testament (see Death, below), his literary estate was bequeathed to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI). The will stipulated that the files were to be transferred to the university from the Institute after the deaths of Margot Einstein and Helen Dukas (see sec. 13E of the will). Enriched by additional originals, copies, and transcriptions, this literary estate became the foundation of the Einstein Archives.

After Einstein’s death in 1955, Dukas, later with the help of Gerald Holton of Harvard University, began a systematic organization of Einstein’s literary legacy. In the meantime, Otto Nathan, the executor of Einstein’s estate, launched a campaign to acquire new material for the archive, also with the help of Dukas and Holton. One of the goals of their project was to prepare the correspondence, writings, and documents for eventual publication by Princeton University Press (PUP) as The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein. PUP established an advisory board in the 1970s to jumpstart the ambitious project.

After Dukas’s death in early 1982, the archive of original documents was moved to Jerusalem late that year. Dukas had been Einstein’s longtime secretary, and after his death, she had become not only a literary trustee but also the first archivist of his papers. In Jerusalem, the first archivist/curator was Manfred Waserman (1988–1989), followed by Ze’ev Rosenkranz (1989–2003), and Roni Grosz (2004 to the present). The archives were shipped from Princeton to the Jewish National and University Library, administratively a part of the HUJI. They are now administered directly by the HUJI’s Library Authority.

Today the archives consist of approximately 80,000 items, a sharp increase from the 10,000 documents estimated in 1978 and 42,000 estimated in 1980. The 80,000 figure includes not only Einstein’s correspondence, writings, and documents, but also copies, transcriptions, translations, and third-party documents that are invaluable in providing context and preparing annotations. The number also reflects an active and continual search for new materials. As John Stachel, the founding editor of The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, noted in his 1980 guide to the duplicate archive that is now located at Caltech, “The Archive itself is a changing thing. Documents are added and sometimes transferred from one place to another. Annota tions may be added, changed, or moved.” Einstein’s diaries, photos, medals, citations, music collection, and books from his personal library are stored in Jerusalem as well, making this the richest of scientific archives.

Duplicate archives for use by scholars have been established at the libraries of Boston University, the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, the Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, and Princeton University in New Jersey. Smaller collections can be accessed in various institutes, colleges, and national archives, to which private parties have donated personal papers that include Einstein correspondence and photographs. Among these are Brandeis University (The Albert Einstein Collection); the Leo Baeck Institute in New York City, particularly useful for its photographs; Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York (Otto Nathan Papers); and the Prussian State Library in Berlin. The Library of Congress in Washington, DC, also has Einstein-related documents and photographs.

Because Helen Dukas and Otto Nathan were the principal figures in establishing the archives, we have placed their biographical information in this section.

Helen Dukas

Helene Dukas, later known as Helen or Helena Dukas, was born on October 17, 1896, in Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, to Leopold and Hannchen Dukas. She was one of seven children. Following the premature death of her mother in 1909, she dropped out of high school to care for her siblings. She later became a kindergarten teacher in Munich and in 1923 moved to Berlin to work as a secretary for a publisher. When the small publishing firm was liquidated five years later, Dukas looked for another job. Her sister Rosa, a friend of Elsa Einstein’s, had heard that Einstein needed a new private secretary because Ilse Einstein, his first full-time secretary, had married Rudolf Kayser and chose to stop working for her stepfather. Rosa alerted Dukas to the open position. After Einstein had employed several temporary secretaries, including Siegfried Jacoby and Edwin Sicradz, Dukas began work in April 1928 as Einstein’s secretary, a position she held until the physicist’s death.

Helen Dukas was not a relative of Einstein’s, but everyone treated her like a family member. She became an enormously important person in Einstein’s life and, after immigrating to the United States, lived in his house with other family members, even after Einstein’s death, for the rest of her life. She never married.

Dukas arrived in Princeton in October 1933 with Einstein and his second wife, Elsa. After Elsa’s death in late 1936, Dukas became housekeeper in the Mercer Street home in addition to carrying out her duties as secretary. On October 1, 1940, she took the American oath of citizenship in nearby Trenton, New Jersey, together with Einstein and his stepdaughter Margot.

Dukas was known for being intelligent, modest, shy, and passionately loyal to Einstein. She was fiercer about protecting his privacy than even Einstein himself. This trait prompted Einstein to nickname her “my Cerberus,” after the hound in Greek and Roman mythology that guarded the entrance to the underworld. Over time, this vigilance and buffering became partly responsible for much of the Einstein mythology. There is no evidence the two ever had a romantic relationship. As if trying to dissuade any rumors, she respectfully referred to him as “Herr Professor” during his lifetime and “the professor” after his death, never as “Albert”—at least in public and in writing. In his last will of 1950, Einstein appointed Dukas, along with his friend Otto Nathan, as co-trustee of his literary estate. The will also stipulated that his personal effects and a sizeable portion of his financial assets be left to her. (See Death, “Last Will and Testament.”)

After Einstein’s death in 1955, Dukas continued to live in the home on Mercer Street with Margot Einstein. She devoted herself to organizing a formal archive of Einstein’s considerable writings and correspondence, a task she undertook first in an office in the basement of Fuld Hall at the Institute and later in a small office on the third floor. She worked faithfully and diligently on the files, adding short notes and cross-references to many of the documents she had filed. Morever, she typed up thousands of transcriptions, mostly of Einstein-authored letters. In addition, she and Einstein’s former assistant Banesh Hoffmann, who became a mathematics professor at Queens College in New York, published two books, Albert Einstein, Creator and Rebel and Einstein, the Human Side.

Dukas continued to come to the office in an Institute shuttle several times a week until her death on February 9, 1982, the result of a ruptured stomach ulcer, at age eighty-five. During her memorial service on February 12 at the Jewish Center in Princeton, Otto Nathan, who had known her for forty-eight years and was close to her for the final twenty-seven, tearfully proclaimed, “When Helen closed her eyes for the last time three days ago, Einstein died a second time. No one was closer to him, no one more dedicated to him. Her purpose in life was to serve Einstein…. She was excited about every new item that came into the archive, as if a part of Einstein himself had returned…. No illustrious scientist could ever duplicate the work she has done.” (From Alice Calaprice’s notes of the service; see also the New York Times’s obituary.) She left her various assets mostly to her sisters and nieces, to Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and to Margot Einstein. She appointed Otto Nathan as the executor of her estate and bequeathed to him a signed, silver-framed photograph of Einstein. (See Einstein Archives 74-628 for a copy of her will.)

Otto Nathan

Otto Nathan was born on July 15, 1893, in Bingen, Germany. An economist, he served as an adviser to the Prussian government during the Weimar Republic from 1920 to 1933 and left Germany after Hitler’s rise to power. After immigrating to the United States, he taught at several universities on the East Coast, including Princeton University, Vassar College, and Howard University, and published two books on Nazi economics. With Heinz Norden, he coauthored Einstein on Peace (1960).

Einstein and Otto Nathan met in Princeton in the mid-1930s, shortly after both established residence there. They quickly developed a trusting friendship that lasted until Einstein’s death. Einstein appointed his old friend as sole executor and a co-trustee of the Einstein estate. With the help of Helen Dukas, Nathan dedicated himself to preserving for posterity Einstein’s established legacy as a secular saint. For years, researchers had tried to construct a more realistic portrait of Einstein but were thwarted by the considerable lengths to which Nathan and Dukas went to avoid sharing information that might be damaging to the physicist’s established reputation. Nathan died in New York City on January 27, 1987, at the age of ninety-three, five years after Dukas. He bequeathed his papers to Vassar College and to HUJI.

Awards, Honorary Degrees, and Honorary Memberships in Foreign Societies

Helen Dukas prepared an incomplete list of awards and honors for the Einstein Archives (Einstein Archives 30-105; see also Reel 65 in the archives). She noted that the citations themselves were left in Germany and that her compilation was likely to be incomplete. However, the archives have since been updated, and we were able to verify all listed honorary degrees with the institutions themselves or with certificates in the archives, thereby adding many previously omitted entries to Dukas’s original short list. (Numbers in brackets are archival numbers; CPAE stands for The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein.)

Awards, Medals, and Miscellaneous Honors

1918 |

Vahlbruch Prize, University of Göttingen [CPAE 8:699n.13] |

1918 |

Müller Foundation honorary prize (Germany) [30-115] |

1920 |

Barnard Medal, Columbia University, for period ending July 17, 1919 (USA) [30-129, 65-012] |

1921 |

Freedom of the City, and Freedom of the State, New York [92-117]; Freedom of the City, New Haven, Connecticut [CPAE 12:453]—while on his first visit to the United States |

1921 |

Nobel Prize in Physics (awarded in 1922) [65-020.3, 85-125] |

1921 |

Election to Royal Society, London [76-427] |

1922 |

Matteucci Gold Medal, Italian Society of Science [30-157, 158] |

1923 |

Diploma of the Golden Book, Jewish National Fund, Jerusalem [65-022] |

1923 |

First “Freedom of the City” award, Tel Aviv (Palestine) [30-170] |

1923 |

Order Pour le Mérite for Science and the Arts (Peace Class) (Germany) [65-075]. Einstein renounced it in 1933. |

1924 |

Einstein Tower, a solar observatory, in Potsdam, near Berlin, completed |

1925 |

Copley Medal, Royal Society (UK) [121-326] |

Jewish-Hispanic Congregation of Buenos Aires, medal [65-077] |

|

1926 |

Gold Medal, Royal Astronomical Society, London [30-214, 79-385]. Also chosen as awardee in 1919 but not confirmed by membership (see Part II, Colleagues, “Arthur Stanley Eddington”) [87-397]. |

1926 |

Medal of the Academy of Athens (Greece) [65-080]. Einstein’s letter of acceptance is dated 1933. |

1929 |

Planck Medal (Germany). First Planck Medal, shared with Planck himself [19-341]. |

1930 |

Key to City of New York, upon his second visit [New York Times, Dec. 14, 1930, p. 1] |

1931 |

French Committee for the Protection of Intellectuals, medal [65-087] |

1931 |

Janssen Medal of the French Astronomical Society, Paris [65-085, 30-255] |

1933 |

Community Church of New York, medal for distinguished religious service [65-089, 69-614] |

1935 |

Franklin Medal, Franklin Institute, Philadelphia [65-056, 88-841 (photo)] |

1940 |

Phi Epsilon Pi National Service Award [88-218] |

1947 |

Foreign Press Award [28-782, 65-113] |

1947 |

Jewish War Veterans of the USA, New York, certificate of honor [65-067] |

1947 |

World Federalist News Award [see Nathan and Norden, Einstein on Peace, p. 404] |

1948 |

One World Award [88-623] |

1950 |

Teachers Union Award, for distinguished service in the cause of education [87-458] |

1953 |

Decalogue Society of Lawyers, merit award [88-518] |

1953 |

Honorary presidency of Hebrew University in Jerusalem [76-487] |

1953 |

Lord and Taylor Award for “intellectual adventuring,” “given to those with a creative and nonorthodox approach to life” [28-979, 72-978, 90-074] |

1955 |

The chemical element 99 was named einsteinium (fig. 7) |

1979 |

Monumental bronze statue unveiled on the grounds of the National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC |

1990 |

Name added to the Walhalla Memorial for “laudable and distinguished Germans,” near Regensburg, Bavaria (Germany) |

1999 |

Time magazine’s “Person of the Century” |

2008 |

Inaugural inductee into New Jersey Hall of Fame, with Thomas Edison and Clara Barton |

Honorary Degrees (Doctor honoris causa)

1909 |

University of Geneva (Switzerland) [30-106 to 109] |

|

1919 |

University of Rostock (Germany), honorary doctor of medicine [65-008] |

|

1921 |

University of Manchester (England) [32-628] |

|

1921 |

Princeton University (USA) [65-015, 84-957] |

|

1922 |

University of Buenos Aires (Argentina) [30-165, 65-019] |

|

1923 |

University of Madrid (Universidad Central) (Spain) [65-023.1] |

FIGURE 7. The element einsteinium. Einsteinium is a synthetic element with atomic number 99. The only element named for a person with a lower atomic number is curium, named for Marie Curie. The element was first observed in the debris of nuclear explosions. It is so radioactive that in this image the quartz crystal of the container next to the element itself is radioactive and glowing brightly. It is one of the heaviest elements to exist in macroscopic quantities. (Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Wikimedia Commons)

1925 |

Republic of Brazil, Faculty of Philosophy [65-038] |

|

1925 |

University of Uruguay, Montevideo, “honorary professor” [65-036] |

|

1929 |

University of Paris (Sorbonne) [65-049, 120-194] |

|

1930 |

University of Cambridge (England) [9-299, 30-247] |

|

1930 |

Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) (Switzerland) [einstein-website.de] |

|

1931 |

Oxford University (England) [120-221] |

|

1933 |

Free University of Brussels, Faculty of Sciences (Belgium) [confirmed by Faculty of Sciences 6/24/11] |

|

1933 |

University of Glasgow (Scotland) [122-538] |

|

1933 |

University of Pennsylvania (USA) [91-776] |

|

1934 |

Yeshiva College (now University) (USA) [28-287, 93-637] |

|

1935 |

Harvard University (USA) [82-484] |

|

1936 |

Regents of the University of the State of New York [confirmed by Regents 6/30/11] |

|

1936 |

University of London (England) [65-060] |

|

1946 |

Lincoln University (USA) [65-066] |

|

1949 |

Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Israel) [28-855, 65-058] |

|

1951 |

University of San Marcos (Peru) [30-308, 60-415] |

|

1954 |

Technion, Haifa (Israel) [28-1058, 69-714] |

Sampling of Honorary Memberships in Foreign Academies of Sciences and Societies (while not a resident of that city or country)

1913 |

Prussian Academy of Sciences, while still in Switzerland (regular membership) |

|

1914 |

German Physical Society, before moving to Berlin (regular membership) |

|

Royal Society of Göttingen, corresponding member [65-005] |

||

1920 |

Royal Danish Academy of Sciences, Copenhagen [30-126, 65-011] |

|

1920 |

Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences, corresponding member, extraordinary fellow [30-127] |

|

1921 |

Association of Engineers and Architects of Spain, honorary member [30-176] |

|

1921 |

Bologna Academy of Sciences (Italy), corresponding member [9-229, 65-013] |

|

1921 |

Gothenburg Society of Sciences and Arts, Sweden [65-016] |

|

1922 |

Institución Argentino-Germana [CPAE, Vol. 13, Chronology] |

|

1922 |

Imperial Japanese Academy of Sciences [CPAE, Vol. 13, Chronology] |

|

1922 |

National Academy of Sciences (USA), foreign associate [30-147, 65-017] |

|

1922 |

Royal Society of Science, Uppsala, Sweden [65-018] |

|

1922 |

Russian Academy of Sciences [30-183, 65-020.2]. Curiously, Einstein’s letter of acceptance is dated 1926 [80-020]. See also 1927 for USSR. |

|

1923 |

Academy of Sciences: Exact, Physical/Chemical, and Natural, of Saragossa (Spain), corresponding member [65-024] |

|

1923 |

Association of Engineers and Architects, “Erez Israel,” stating that Einstein is “the glory of our people” [65-021] |

|

1923 |

German Medical Science Society of Prague, honorary member [65-025] |

|

1923 |

Göttingen Academy of Sciences (Germany), corresponding member [65-026] |

|

1923 |

London Mathematical Society [65-028] |

|

1923 |

Royal Academy of Sciences: Exact, Physical, and Natural (Madrid, Spain), corresponding member [65-023] |

|

1923 |

Royal Academy of Sciences and Arts, Barcelona (Spain), corresponding member [121-122] |

|

1924 |

American Academy of Arts and Sciences (Boston, USA) [65-029] |

|

1924 |

Society of Physics Research, Athens (Greece) [65-030] |

|

1925 |

Academy of Exact, Physical, and Natural Sciences, Buenos Aires (Argentina) [65-033] |

|

1925 |

Academy of Sciences, Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) [65-037] |

|

1925 |

Argentine Scientific Society, Physical-Mathematical-Natural Sciences, Buenos Aires [65-033] |

|

1925 |

Ezrahi Hospital, Buenos Aires, honorary member [65-031] |

|

1925 |

National University of La Plata, Argentina [65-034] |

|

1925, |

Polytechnic Association of Uruguay [65-039] |

|

1926 |

Royal Philosophical Society of Glasgow [65-041.1] |

|

1927 |

USSR Academy of Sciences, Leningrad [30-221, 120-602] |

|

1928 |

Royal Irish Academy [30-230, 65-045] |

|

1928 |

Royal Swedish Academy of Science [65-046] |

|

1930 |

American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia [65-051] |

|

1931 |

American Physical Society [30-254] |

|

Royal Academy of Sciences and Art, Belgium, Science Section [65-053] |

||

1933 |

French Academy of Sciences, Paris [unable to verify] |

|

1933 |

Academy of Sciences, Athens [122-531] |

We did not find any foreign memberships awarded after Einstein’s immigration to America.

Career

List of Years, Job Titles, and Employers

1900 |

Einstein graduates from the Swiss Federal Polytechnical School in Zurich |

1901, Summer |

Substitute teacher at the Technical School (a secondary school), Winterthur, Switzerland |

1901, September |

Tutor at private boarding school, Schaffhausen, Switzerland; begins work as doctoral student, University of Zurich |

1902 |

Technical Expert, Third Class, Swiss Federal Patent Office, Bern, examining patents |

1906 |

Receives doctorate from University of Zurich and becomes Technical Expert, Second Class, at patent office |

1908 |

Unsalaried lecturer (Privatdozent) at University of Bern after submitting a Habilitationsschrift (postdoctoral research paper); does laboratory work with Albert Gockel at University of Fribourg in Switzerland |

1909 |

Extraordinary Professor of Physics, University of Zurich |

1911 |

Professor of Theoretical Physics and Director of the Physics Institute, German University of Prague |

1912 |

Professor of Physics at ETH (Federal Institute of Technology, formerly the Swiss Federal Polytechnical School) |

1914 |

Member of Prussian Academy of Sciences; Professor of Physics, University of Berlin |

1917–1933 |

Director of Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Physics (KWIP), Berlin, while still teaching at the university; also delivered occasional series of lectures at University of Zurich. Max von Laue became deputy director of KWIP in 1922 and took over Einstein’s administrative duties. |

1920–1930 |

Special Professor (bijzonder hoogleraar) of Physics, University of Leyden; made regular visits from Berlin to lecture there |

1933–1945 |

Professor of Physics, School of Mathematics, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, New Jersey |

On entering the Swiss Federal Polytechnical School (later the Federal Institute of Technology, ETH) in Zurich in 1896, Einstein set his sights on becoming a secondary-school teacher in mathematics and physics, graduating in 1900 with good if not exceptional marks. Unable to find long-term teaching contracts, he took a position at the Swiss Federal Patent Office in Bern. Beginning in 1907, he offered poorly attended lectures at the University of Bern as a Privatdozent (unsalaried lecturer). His academic breakthrough came two years later, when he was appointed ausserordentlicher (extraordinary, akin to an associate) professor at the University of Zurich. When Einstein accepted a full professorship at the German University of Prague, a number of students in Zurich, in a petition of June 23, 1910, protested his departure, praising his ability to present the most difficult problems in theoretical physics in a clear and intelligible manner (“Student Petition,” June 23, 1910, CPAE, Vol. 5, Doc. 210; Einstein Archives 70-159). Almost immediately after his arrival in Prague, he was wooed by his alma mater to return to Zurich. In assessing his candidacy for the faculty position at the ETH, a colleague touched on Einstein’s teaching abilities, emphasizing that while he was not a good instructor for the lazy auditor, he had a knack for compelling his audience to think along with him (Heinrich Zangger to Ludwig Forrer, October 9, 1911, CPAE, Vol. 5, Doc. 291; Einstein Archives 80-044). He returned to the ETH in fall 1912.

Less than two years later, Einstein was appointed a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin. His official duties there did not include teaching, though he felt an obligation to offer courses at the University of Berlin and did so periodically. His dismissal from the Prussian Academy in 1933 effectively ended his teaching career, although he lectured occasionally at Princeton University during the early years of his residency at the Institute for Advanced Study.

Places of Employment

PATENT OFFICE, BERN

The young Einstein’s first “real” position was hard won, as shown by his father’s concern in the following letter to Wilhelm Ostwald, a physical chemist at the Univerity of Leipzig and future Nobel laureate. The letter was sent from Milan on April 13, 1901:

Please forgive a father who, in the interest of his son, presumes to write to you, esteemed professor.

Let me begin by telling you that my son, Albert Einstein, is 22 years old, studied at the Zurich Polytechnic for 4 years, and last summer passed his final examinations in mathematics and physics with distinction. Since then he has unsuccessfully tried to secure a position as Assistent that would allow him to broaden his training in theoretical and experimental physics. All those capable of evaluating his talents have praised him. In any case, I can assure you that he is extraordinarily industrious and diligent and is passionately dedicated to his science.

My son feels very unhappy in his current state of unemployment and is becoming increasingly concerned that he is going off-track with his career and losing touch. Furthermore, he is distressed that he has become a burden for us, since we are people of modest means.

Because my son admires you, highly esteemed professor, above all others who are currently engaged in the field of physics, I have allowed myself to turn to you with the kind request that you read the paper he published in Annalen der Physik, and perhaps to write him a few lines of encouragement so he will regain his joy of living and creating.

If it would be possible for you to arrange for him to obtain an Assistent’s position either now or next fall, my gratitude would be boundless.

Please again excuse my impertinence in writing you these lines, and allow me to note that my son does not know that I have taken this unusual step. [Einstein Archives 71-549]

Ironically—and apparently without his father’s knowledge—Einstein had written to Ostwald himself only four weeks earlier. There is no evidence that Ostwald ever replied to either of the Einsteins. Within a year, however, an entry-level position for a patent clerk opened up at the Swiss Federal Patent Office in Bern. Luckily for Einstein, his friend Marcel Grossmann’s father knew the director of the office, Friedrich Haller. The elder Grossmann sent a letter of recommendation to Haller on Einstein’s behalf. In June 1902, the young physicist received a provisional appointment as technical expert, third class, and in early 1906 he was promoted to expert, second class. In accordance with Swiss patent law, his job required that he examine and review patent applications for efficacy, not novelty. This kind of work apparently gave him abundant time to think about other topics closer to his heart; whether he did so during or after hours is unclear. During his tenure at the patent office, Einstein published his best-known papers, apart from the later work on general relativity. He stayed there until October 1909, while also holding a part-time position as lecturer at the local university.

UNIVERSITY OF BERN

In June 1907, Einstein submitted his dissertation and seventeen papers, including those from the annus mirabilis, to the University of Bern in an attempt to obtain a teaching position. The faculty rejected Einstein’s petition because he had failed to submit a “specialized investigation.” In early January of the following year, he overcame this pedantic objection and submitted a Habilitationsschrift (similar to a postdoctoral thesis) on blackbody radiation that was accepted toward the end of February. Almost immediately, he was required to give an inaugural lecture, which he titled “On the Limit of the Validity of Classical Thermodynamics,” and presented it to an academic audience on February 27. The thesis and lecture were a significant step in establishing his eligibility for a professorship at the University of Zurich in 1909. In April, he began teaching his first course on the molecular theory of heat while both continuing to work at the patent office and also working at the laboratory of Albert Gockel in Fribourg for two months on the construction of a small induction machine (the so-called Maschinchen). He left the university and the patent office in 1909 to accept an associate professorship in Zurich.

UNIVERSITY OF ZURICH

In February 1909, a second teaching position in physics was created at the University of Zurich. Einstein was recommended for it by Alfred Kleiner, who had been his doctoral adviser at the university. It is likely that Kleiner had been grooming Einstein for the position for some time while awaiting the necessary funding (see letters from Alfred Kleiner, January 28, 1908, and February 8, 1908, CPAE, Vol. 5, Docs. 78 and 80; Einstein Archives 29-249 and 29-252. See also Schulmann, “Einstein at the Patent Office”). The appointment began in winter semester 1909, that is, in October. The previous July, he had received his first honorary doctorate—from the University of Geneva, and in October, Wilhelm Ostwald, who apparently had ignored Einstein’s application to Leipzig back in 1901, nominated Einstein for the Nobel Prize. He would receive several more nominations before receiving the award for 1921 (see Part II, Nobel Prize). He stayed in Zurich until January 1911, when he resigned to accept a position in Prague.

GERMAN UNIVERSITY OF PRAGUE

On January 6, 1911, Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary appointed Einstein to the physics chair at the German University of Prague, also known as Charles University. Einstein resigned his position in Zurich and moved his family to Prague in April, when he also became director of the university’s Institute of Theoretical Physics. By the fall of that year, Einstein was already approached about positions in Utrecht and at the Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich. He accepted an offer from the latter and left Prague the following July.

FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (ETH)

When Einstein was a student there, the ETH was named the Swiss Federal Polytechnical School. In 1911, it was changed to the Federal Institute of Technology (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule). At the end of January 1912, at the age of thirty-two and less than twelve years after he had left as an undergraduate, he accepted an appointment there as Professor of Theoretical Physics, gained largely through the efforts of his friend, Heinrich Zangger. Because he still had teaching obligations in Prague, he did not begin teaching at the ETH until October. Besides the usual teaching and research duties, he also assumed various administrative responsibilities, such as serving as an examiner for mathematics students. He stayed at the ETH until 1914.

PRUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, UNIVERSITY OF BERLIN, AND THE KAISER WILHELM INSTITUTE OF PHYSICS

In mid-July 1913, two prominent members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, Max Planck and Walther Nernst, visited Einstein in Zurich and sounded him out for special membership in the academy. In contrast to regular members, who earned only an annual honorarium, he was offered a handsome salary. In keeping with the two-track German system in which academies were devoted to research and universities to teaching, Einstein’s appointment would emphasize research concerns, though he was free to offer courses at the university. The men also discussed with Einstein the creation of an institute of physics in Berlin, to be established by the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, and invited him to become its director. In November, his membership in the academy was confirmed, and Einstein resigned from his position at the ETH, formally accepting the Berlin offers. He moved to Berlin in spring 1914, but his wife Mileva and their two sons, who had joined him briefly, soon returned to Zurich because of the couple’s marital problems.

The establishment of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Physics (KWIP), privately financed by Leopold Koppel, a German banker and entrepreneur, was delayed for three years, until October 1917, because of the outbreak of the First World War. According to an explanatory note that Einstein sent to the Berlin mass-circulation newspaper, Vossische Zeitung, on April 1, 1923, the KWIP was fundamentally an organization that funded scientific research in both theoretical and experimental physics and had no physical facilities such as a building or laboratories. The KWIP did not move into a building of its own until 1938, five years after Einstein had left for the United States. Einstein’s job as director was to solicit research proposals that the institute would review and either fund or reject. Even though he was contractually not obliged to do so, Einstein chose to teach at the University of Berlin both before and after he became director of the new institute. He held this position until 1933, when he resigned from the Prussian Academy and the Institute after Hitler came to power.

Although Einstein worked mostly in Berlin, he also accepted a visiting lectureship at the University of Leyden, which brought him to the Netherlands regularly for several years beginning in 1920. He had been strongly encouraged to do so by Paul Ehrenfest, H. A. Lorentz, and Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, close colleagues in the Netherlands. In fact, Einstein had been chosen to replace the retired Lorentz as professor of theoretical physics but turned down the offer. Paul Ehrenfest, who was instrumental in attracting Einstein as a regular lecturer until April 1930, succeeded him instead.

Sources: CPAE, Vols. 8–14; Carlo Beenakker, Leyden, personal communication; Dirk van Delft, “Albert Einstein in Leiden,” Physics Today, April 2006, pp. 57–72.

INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY, PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY, USA

Since its formal inception in 1930, the Institute’s mission has been to attract the world’s best scholars, allow them to work in a harmonious and collegial community of internationally re nowned researchers without the burden of teaching undergraduate students, and earn generous salaries while doing so.

From 1933 until 1940, the Institute was given temporary quarters on the Princeton University campus, in Fine Hall, the old mathematics building (now called Jones Hall). Because of this early logistical connection to the university, many outsiders are under the impression that the Institute is a part of the Ivy League institution. In 1940, the Institute’s small faculty, including Einstein, moved to a newly built 800-acre campus in a rural and wooded part of Princeton. Einstein retired from the Institute in 1945 but continued to occupy an office in Fuld Hall, the main building, until his death ten years later.

Citizenships and Immigration to the United States

Born in Germany to parents whose families had deep roots there, Einstein was a Württemberg (German) citizen by birth. In 1896, while attending school in Aarau, Switzerland, while his family was living in Italy, Einstein, with his father’s approval, resolved to give up his Württemberg citizenship. His intent likely was to avoid mandatory military service in the German army when he turned seventeen. To formalize his decision, he requested his release from German citizenship in late January 1896. He was encouraged in the process by Jost Winteler, with whom he boarded while attending the Aargau Cantonal School and who was openly disdainful of the “religion of might” in Germany.

In 1899, Einstein began to save the money required to apply for Swiss citizenship, which would allow him to seek employment in the Swiss civil service, including teaching positions. After the local police department issued a report attesting to his “good conduct,” Einstein also passed the muster of the naturalization commissioners during a personal interview. On February 21, 1901, three weeks before his twenty-second birthday and a week after he paid the citizenship fees, Albert Einstein was declared fit to be a citizen of the municipality and canton of Zurich and, thus automatically, of the Swiss Confederation.

Einstein returned to Germany in 1914 to accept a position as a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, as professor of physics at the University of Berlin, and eventually as director of the newly established Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Physics. Because these were civil service appointments, he was required by law to be a Prussian (German) citizen, a fact of which he was made aware while still in Switzerland. His only condition for accepting the positions was that he be allowed to retain his Swiss citizenship (see letter to Heinrich Lüders, March 24, 1923, CPAE, Vol. 13, Doc. 454; Einstein Archives 79-362), and this request was honored. In fact, the academy was so eager to grant him membership that it ignored the requirement for him (see Grundmann, The Einstein Dossiers, pp. 168–174). During the First World War and after, he continued to travel on a Swiss passport.

The academy’s perspective changed when Einstein became the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922, retroactively for 1921. Though the prize was awarded to individuals, it was perceived by the public and in official circles as a national honor. Raison d’état demanded that Einstein and his celebrity be linked closely to the Prussian state. After German ambassador Rudolf Nadolny stood in for the absent Einstein at the awards ceremony in Sweden, the envoy requested clarification from his government of possible Swiss citizenship claims on Einstein. The academy responded that, whatever else had happened before, Einstein had taken the civil-service oath of allegiance to Germany and Prussia in July 1920 and March 1921, respectively, thereby unequivocally making him a German citizen. This information was conveyed to Einstein with the assurance that his Swiss citizenship remained unaffected (see letter from Heinrich Lüders, February 15, 1923, CPAE, Vol. 13, Doc. 431; Einstein Archives 29-179.06). Urged to finally resolve the matter, Einstein met with a ministerial representative, after which he issued the following statement: “The question has been raised at the Academy whether in addition to my Swiss citizenship I also possess Prussian citizenship. At the Academy’s request, I had a discussion with Dr. [Otto] von Rottenburg at the Ministry of Culture about this. He was adamant in his opinion that my employment by the Academy was linked to the acquisition of Prussian citizenship, as there are no grounds to the contrary to be found in the records. I raise no objection to this opinion” (“Note on Prussian Citizenship,” February 7, 1924, CPAE, Vol. 14, Doc. 209; Einstein Archives 79-370). However reluctantly, Einstein had officially acknowledged his Prussian citizenship.

Dual citizenship became an issue again after Hitler’s election as German chancellor in January 1933. A month later, upon returning to Europe from his third trip to Pasadena, California, Einstein announced that he would not set foot in Germany again and that he was resigning from the academy. Days before Einstein landed in Belgium, the new German government declared a nationwide boycott of Jewish businesses, and a prominent right-wing newspaper published a defamatory caricature of Einstein as a delusional malingerer who imagined himself to be a Prussian. From Ostend in Belgium, he and Elsa wrote the German Foreign Office, requesting their release from German citizenship.

The reaction of his former colleagues in the Academy to his resignation was a bitter disappointment to Einstein. With the exception of Max von Laue, members did not speak out against the academy’s official declaration that Einstein had brought exclusion upon himself by spreading distortions abroad about the new regime. The process of officially releasing him from German citizenship was more complicated and far lengthier than usual, as Einstein’s case became a pawn in an internal power struggle between governmental ministries. The Foreign Ministry argued that Einstein had forced the citizenship issue by withdrawing from the academy and that his citizenship should thus be allowed to lapse. The Ministry of the Interior took the harder line that he had to be expelled because of the lies he had told abroad about the Nazi regime. After ten months, the latter won the argument, and in March 1934, almost a year after his initial request, Einstein was once again a Swiss citizen only. Presumably, the irony was not lost on him that in 1922, when he received the Nobel Prize, the Prussian government had gone to great lengths to ensure that he was a German national, and now, a decade later, it brutally stripped him of that citizenship. In addition, on May 10, 1933, on the very day of the Nazi book burning of “un-German” works, including those of Jewish authors, the Gestapo informed the Einsteins that their financial assets in Germany had been confiscated. Expropriation of their summer house in Caputh and of Einstein’s sailboat followed soon after.

Determined never to live in Germany again following their return from America in March 1933, the Einsteins resettled in Coq sur Mer, Belgium, while Einstein considered a number of appointments in “Princeton, Madrid, Paris, Oxford” (see letter to Paul Langevin, June 4, 1933; Einstein Archives 15-397). Ilse and Rudolf Kayser had meanwhile arranged to have Einstein’s papers from the Berlin apartment and the house in Caputh sent to safety in France by diplomatic pouch.

By September, Einstein had accepted the Princeton appointment. After receiving death threats in Belgium, he and his wife spent their last month in Europe enjoying the protection and hospitality of the British naval commander and politician Oliver Locker-Lampson near his home in Cromer, Norfolk, England. The future archives were shipped to the United States along with other belongings retrieved from the Einsteins’ Berlin apartment (see also Archives). With Helen Dukas and Walther Mayer, the Einsteins boarded the SS Westmoreland in Southampton for another long voyage to America, this time, as it turned out, to live there permanently. They arrived in New York Harbor on October 17, and from there traveled to Princeton, New Jersey, where Einstein had accepted an offer from the co-founder of the Institute for Advanced Study, Louis Bamberger. Ilse, Margot, and their husbands remained in Europe. Ilse fell ill and Elsa returned to Europe to be at her bedside; Ilse died in France in 1934. Elsa then sailed back to America once more, this time with Margot, her younger daughter. The widowed Rudolf immigrated a year later. Margot’s husband, Dmitri, eventually came to the United States as well. (See also Family.)

Einstein had entered the United States in 1933 with a visitor’s visa. Under U.S. immigration law at the time, permission to become a citizen could be obtained only through an American consul in a foreign country. In late 1933, however, Congressman F. H. Shoemaker sent a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt recommending that he extend U.S. citizenship to Einstein by executive order (December 1, 1933; Einstein Archives 33-128). The following year, it was proposed that Einstein be granted citizenship by an act of Congress, but he declined. Instead, he and his family and Helen Dukas went to Bermuda to apply for citizenship in May 1935 (fig. 8). The American consul on the island hosted a festive dinner in Einstein’s honor and gave his guests legal permission to enter the United States as permanent residents. In 1937, another movement was planned to grant him citizenship more quickly through an Act of Congress (see newspaper account, February 20, 1937; Einstein Archives 93-220). Finally, three years later, in 1940, Einstein, Margot Einstein, and Helen Dukas became citizens through regular channels as they completed the required five-year waiting period and took the oath of allegiance in Trenton, New Jersey (fig. 9). Elsa had died in December 1936, and thus did not have the opportunity to become an American citizen.

FIGURE 8. Citizenship application, “Declaration of Intention.” The Einsteins, according to immigration laws at the time, were required to re-enter the United States from a foreign country, and they chose Bermuda, a British Overseas Territory, in June 1935, five years before citizenship was granted. (Wikimedia Commons)

FIGURE 9. Einstein being congratulated by Judge Phillip Forman after taking the oath of U.S. citizenship in Trenton, NJ, on October 1, 1940. (Photo by Al Aumuller, New York World Telegram & Sun; Library of Congress)

Domiciles

1879–1880, Ulm

1880–1894, Munich

1895, Milan

1895–1896, Aarau, canton of Aargau, Switzerland

1896–1902, Zurich

1902–1909, Bern

1909–1911, Zurich

1911–1912, Prague

1912–1914, Zurich

MAP 1. Some of the towns and cities within Europe mentioned in this book, in which Einstein and his family lived and to which he traveled for work, conferences, and pleasure. A few major cities are included as reference points.

1914–1933, Berlin; vacation home in Caputh, 1929–1932; winter trips to Pasadena, 1930–1933

1933, Coq sur Mer, Belgium, while fleeing Hitler and before immigrating to the United States

October 1933–April 1955, Princeton, NJ (fig. 10); summers in Huntington, Long Island, NY; Peconic, Long Island, NY; Saranac Lake, NY; Watch Hill, RI; Old Lyme, CT; Deep Creek Lake, MD.

FIGURE 10. The Einsteins’ home on Mercer Street in Princeton, NJ. (Photo by Dmadeo, Wikimedia Commons)

Education and Schools Attended

(See also Part III, Education: Einstein’s Views)

Educational Background

As a pupil in Munich, Einstein resisted the rote memorization that characterized the usual school curricula. Instead, he devoured readings that engaged his curiosity, such as Aaron Bernstein’s multivolume compendium, Naturwissenschaftliche Volksbücher (Natural Science Books for a General Readership). His lack of respect for authority apparently led to disciplinary problems in his Munich Gymnasium (secondary school), which he left in midterm as a fifteen-year-old in 1894, though one teacher complimented him on his mathematical abilities (see Kayser, Albert Einstein: A Biographical Portrait, pp. 42–43). He completed his secondary-school education in Switzerland, the youngest pupil in a class of fifteen, at the Aargau Cantonal School in the town of Aarau, where he found coursework and teacher attitudes more conducive to instilling the independence of thought he prized (fig. 11). The school record reflects Einstein’s contentment: his grades were consistently excellent in spite of a persistent myth that he was a poor pupil as an adolescent. (See Myths and Misconceptions.)

FIGURE 11. The Aargau Cantonal School in Aarau, Switzerland, which Einstein attended 1895–1896 during his last year of secondary schooling, before attending the Swiss Federal Polytechnical School (ETH). (ETH, Zurich)

In 1895, at the age of sixteen, two years younger than the regular age of admission, Einstein had tried to enter the Swiss Federal Polytechnical School (later ETH) in Zurich but failed the entrance exam, though his marks in physics and mathematics were high. The rector wrote that he needed another year to become more mature and increase his language skills (see Albin Herzog to Gustav Maier, September 25, 1895, CPAE, Vol. 1, Doc. 7; Einstein Archives 71-660). Einstein’s successful leaving examination from the Aargau Cantonal School granted him automatic admission to the ETH the following year. He graduated with a teaching diploma in 1900 and soon began work toward a doctorate at the University of Zurich (at that time, the Poly did not grant doctorates) while also teaching part time and later working at the patent office. (See CPAE, Vol. 1, for Einstein’s early education.)

Schools and Universities Attended

Petersschule, Munich, Germany (Catholic primary school), fall 1885–1888

Luitpold Gymnasium, Munich, Germany (secondary school), fall 1888–December 1894

Home study in Milan, January–fall 1895

Aargau Cantonal School, Aarau, Switzerland (secondary school), fall 1895–fall 1896

Swiss Federal Polytechnical School (ETH) (university level), fall 1896–summer 1900

University of Zurich (doctoral work), fall 1900–summer 1905; doctorate conferred, January 1906

University of Bern (Habilitation), 1908. A Habilitation—a postdoctoral thesis—is required of doctoral recipients in many European countries to prove they are capable of teaching at a university level and conducting independent, high-quality research. It qualifies holders to supervise doctoral students later in their careers. An “inaugural lecture” was also required to demonstrate one’s ability to teach.

Einstein Papers Project (EPP) and The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein (CPAE)

(See also Archives, above; and Death, “Last Will and Testament,” below.)

Herbert S. Bailey, the director of Princeton University Press (PUP) during the negotiations in the 1970s and 1980s that eventually led to the publication of the Einstein archives, called the Press’s publishing endeavor “the greatest of its kind in this century.” Its goal was ambitious: to present to the public Einstein’s published and unpublished writings and correspondence, including his personal and scientific correspondence; the scientific, political, and humanitarian writings that had made him famous throughout the world; and his travel diaries, class notes, and vital documents. The volumes would on occasion also include third-party materials that would help document and provide context for Einstein’s thoughts and activities as they played out over his lifetime. The series, to be called The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, was at the time projected to comprise at least twenty volumes and take twenty years to complete. Publication began in late 1985 with the submission of a preliminary manuscript of volume 1 to PUP. At present (2015), approximately thirty years later, the estimates are quite different: the Einstein Papers Project has completed fourteen volumes, and approximately sixteen more are projected to be published before the series is considered complete, most likely before the middle of the century.

When Bailey and the Einstein Papers Advisory Board announced their early predictions, they had estimated that the archive contained about 10,000 documents. The count had more than quadrupled, to 42,000, by the time a computerized index was finished in 1980. Following a continual and successful search for new documents by the editors, the number has almost dou bled—to approximately 80,000 items today, though many of them consist of duplicates and various transcriptions, some translations, as well as material necessary for editorial annotations.