January 10, 1969, Twickenham Film Studios, Middlesex

On Thursday January 2, 1969, The Beatles arrived at Twickenham Film Studios to shoot a documentary. The subject was a live concert the band was now planning to undertake, their first in three years. The idea was to film the band rehearsing and then playing the gig itself. What made the concert special was that the set list would comprise solely of material from their new album. That album would then be released as a live document.

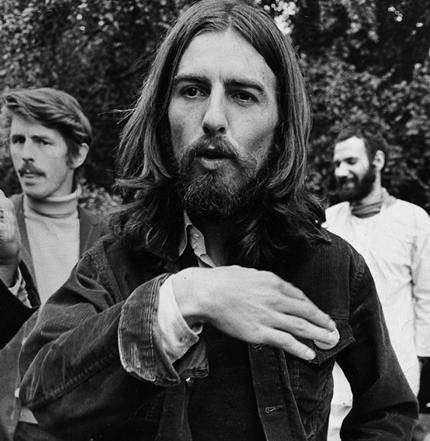

This was typical of Beatle thinking. Other bands released live albums of old material. As ever, this band went the other way. The end was approaching but they still wanted to break new ground. Only things did not work as planned. At Twickenham, the band began bickering to such an extent that on January 10 George Harrison, having viciously argued with Paul and later John, announced that he was quitting the band. He suggested the band place ads in the music papers to find a new guitarist.

The Beatles’ recent single “Hey Jude” was partly to blame and so were many other things, ranging from John’s disillusionment to the precarious financial state of the band. By the end of 1968 “Hey Jude” had sold five million copies. It had hit number one all over the world and given the band their longest ever stay at the top of the US singles chart. Clocking in at seven minutes, it was the longest single ever to chart. It also reminded the band of their power to create sublime pop music that spoke to millions.

The song had been inspired by John and Cynthia’s divorce. Driving to John’s house to work one morning, Paul began thinking about Julian, John and Cynthia’s son. It was typical of him to do so. Paul had grown close to Julian. John, like his father before him, had never paid his son the attention he deserved and that pushed Paul into acting almost like a surrogate dad to Julian.

“Paul and I used to hang out more than Dad and I did,” Julian Lennon once confirmed. “We had a great friendship going and there seems to be far more pictures of me and Paul playing together at that age than there are pictures of me and Dad.”

To promote the single the band traveled to Twickenham to perform it for the popular TV show Frost On Sunday. An invited audience watched as they ran through both “Hey Jude” and its B-side, “Revolution.” After the highly tedious time spent making The Beatles double album (The White Album), the band was pleasantly reminded of the joys of performing.

Meanwhile, “Hey Jude” was released on August 30, 1968 and dominated the rest of the summer. McCartney even took it to the party thrown by The Rolling Stones to launch their new Beggars Banquet album and had the DJ play the single. In doing so, he totally usurped Mick and the boys’ evening. Everyone went home talking about the amazing new Beatles single.

John was not too happy, though. He had put forward his song, “Revolution,” as the A-side but the band did not think it strong enough. Lennon felt they missed the point. John was not too concerned with chart positions. He was now very keen to produce art of an instant nature, and communicate through song his current thinking on the political upheavals that had swept the world in 1968.

Lennon’s position was, for once, muddied. Although his natural instincts were against authority, he was also set against violent revolution, arguing that, “if you want peace you won’t get it with violence.” Ironically, as Lennon looked for ways as a pop star to create an equal society, money came to haunt him. Money had always been a source of worry for Lennon. Even at the height of Beatlemania, he felt insecure about his earnings. He told journalist Maureen Cleave in that interview, that he had taken some of his cars back to be resold, until his accountant had assured him that he was rich enough not to have to take such an action.

Lennon always felt money would slip away from him as so much in his life already had—mother, father, best friend, manager. Furthermore, to his—and the band’s—great annoyance, he could never fully understand how Beatle money worked. Accountants told him he was a millionaire—on paper. What did that mean? Is the money in the bank? Well, it is—and it isn’t. Uh?

One thing he did understand was a note an accountant had recently slipped him which stated that if the Apple organization carried on in the same manner, The Beatles would be broke in six months. Apple was hemorrhaging money. It was a mess. Every week, new ventures were announced. An Apple School, run by John’s old gang member, Ivan Vaughan, was put on the To Do list. As was Apple Publicity, Apple Management, Apple Books, Apple Films, Apple Fashions. There was also Apple Electronics, headed by Magic Alex, who recommended a young man named Caleb be brought in to read the I Ching before any major business decisions were made.

In hindsight, it is perhaps unfortunate that Caleb was not able to foresee the defective nature of Magic Alex’s schemes. Despite the talk, he had not been able to create a force field to protect the band’s homes nor had he been able to make loudspeakers out of wallpaper. He was now building a new 16-track studio in the basement of their offices at 3 Savile Row. The building was expensive and seemed to be full of people taking all the drink and drugs their Beatle expense accounts could handle. Only Apple Records was in profit. The singer Mary Hopkins had scored a serious chart hit with her song “Those Were The Days” (adapted from a Russian folk song McCartney admired).

George had no interest in Apple whatsoever. In fact the whole operation must have been agony for him. After all in days gone by George was the man who kept his eye on the finances. It was he who badgered Epstein constantly about monies owed and money due. Now Apple was eating up all that cash and he could only stand by and watch. “I was still in India when it started,” he explained. “I think it was basically John and Paul’s madness—their egos running away with themselves or with each other.” Note the use of the word “ego.” If Yoko had changed John, then India had changed George. His enthusiasm for its people, its music and its religious practices knew no bounds. His discovery of meditation had now brought him to the same understanding that John had taken from Timothy Leary and his LSD-inspired teachings; the ego must be dissolved before nirvana can be achieved.

Yet, as George sought to rid himself of worldly goods and desires, he was also attempting to remain a Beatle. The two were not compatible. The lengthy bouts of meditation that George undertook—sometimes up to eight hours—had convinced him that the world and its ways were meaningless. Suddenly Beatle Land seemed silly compared with finding God. The problem Harrison had was that he was human and sometimes not able (or willing) to put aside all pleasures. By all accounts George seems to have vacillated between clean living and the rock’n’roll lifestyle, a duality that would last all of his days.

Meditation and India also changed his relationships within the band. George was always third in the hierarchy. To John and Paul, George was the little kid who had followed them around hoping for attention. In The Beatles they still treated him as such. That changed in 1965 when John and George took LSD together and bonded. Then John met Yoko and problems developed. George like Paul was aghast at losing the gang leader to a woman, an avant-garde artist of all people. (George viewed the avant-garde scene and then uttered the phrase, “Avant garde a clue.”)

George was not at all happy to be in Yoko’s company at work. He was not too keen about Paul being there either. During the sessions for The Beatles double album, with John wrapped up in Yoko, Paul had taken charge, taking the band through endless takes of his songs until he was satisfied. George saw his behavior as ego driven and felt that Paul’s anger and frustration at the recent dissolution of his relationship with Jane Asher, plus John’s relationship with Yoko, was now being taken out unfairly on both him and Ringo.

It also did not help that throughout his Beatle career George had always struggled to have his compositions accepted by John and Paul; both men often considered themselves superior in that department and often put his songs down or refused to record them. George took their attitude on the chin. The gang moved as one back then. Dissent in any way hindered its progress. But now …

For the Let It Be sessions, George had written “All Things Must Pass,” “Hear Me Lord” and “I Me Mine.” Only the last of these songs would be recorded by The Beatles. The other two, plus many more the band had passed on, would go on to make up his highly acclaimed debut solo album, All Things Must Pass.

It did not help that George had recently spent time with Bob Dylan up in Woodstock and written a song with Dylan called “If Not For You.” John and Paul had never once offered to write a song with him. They had helped him with his compositions but not reached out to him like Dylan had. That rankled badly.

Perhaps the problem John and Paul had with George’s new material was the mystical nature of the songs. Indeed, George’s spiritual development was now starting to put down roots. Since 1965 George had explored all kinds of different religions but had settled of late with the Hare Krishna movement, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. He was impressed by the followers’ humility and lack of interest in Western consumerism, unlike the Maharishi who swanned around in a private helicopter. George befriended them, gave them money and wrote his most famous song, “Something,” with Krishna in mind. One evening at home, George explained that he had to change the lyrics. A Beatle singing about “he” rather than “she” would be likely to cause misunderstanding and so the lyrics were changed.

On the day he stormed out of Twickenham, the band plus Yoko spent the afternoon jamming: Ringo played weird drums, Yoko did her screaming bit, John supplied feedback guitar and Paul rubbed his bass up and down his amplifier. Two days later, the band plus Yoko arrived at Ringo’s house to try to sort out their differences. George instantly raised his objections, saying that it had been agreed that the meeting should be limited to the four band members only. John said he had not been told that and George said he didn’t believe him and walked out, heading up to his parents’ house in Liverpool.

On the Wednesday, all four Beatles convened again at the Apple offices. Progress was made. George agreed to return but only on the condition that they agree to drop the live-concert idea, get out of Twickenham and head into the studio that Magic Alex had built for them to make a new album. With the band back in harmony, they marched downstairs to the studio only to find that Magic Alex’s plans had proved faulty and the studio would have to be taken apart and rebuilt. As Harrison looked at the mess, he must have thought this was the perfect metaphor for Apple, a beautiful idea, realized at great cost and unable to function properly.

Given the tensions between the band, one has to ask why they did not split up there and then. Why carry on with this unwieldy beast that was only causing grief? Part of the reason was that sometimes there were moments of real magic, moments that reminded them of their special nature, moments that returned them to much happier times.

On January 30 the band finally hit on the perfect venue for their gig to be filmed. They would play unannounced on the roof of the Apple building. Traffic would stop, chaos would ensue—it was perfect. The band set up and started playing. As they went through tracks such as “Get Back” and “Don’t Let Me Down,” obviously enjoying the situation, word reached them that the police were on their way. All of them had the same thought, great, let’s get busted, what an ending to the film that will make. However, this was not Hollywood. The police did not drag Ringo screaming and kicking from his drums. They did not frog march the other three into vans. They simply tried to turn the electricity off.

The Beatles last live performance was on the rooftop of the Apple building, on January 30, 1969. They played for about 45 minutes, and then the police stopped the show.

The event served to reunite the band temporarily but it did not last. The fact was that although most of them were ready to quit, financially they could not afford to do so. It was ironic; the band that had help liberate the world was now the band that held its members prisoners.