January 27, 1970, The Dorchester Hotel, London

Two Americans dropped down into London to fight for control of The Beatles, and they could not have been more different. Lee Eastman was elderly, Ivy League educated, a cultured, assured man, and father, of course, to Linda. Allen Klein was raised in an orphanage. He was brash, spoke tough and was driven by money. The choice divided the band. McCartney was loyal to his father-in-law while John, George and Ringo felt far more affinity with the streetwise Klein.

Lee Eastman had been called to London by his son-in-law. McCartney believed The Beatles were the best in the world and therefore everything around them should be at a similar level—for him Lee was the perfect person to take over as manager.

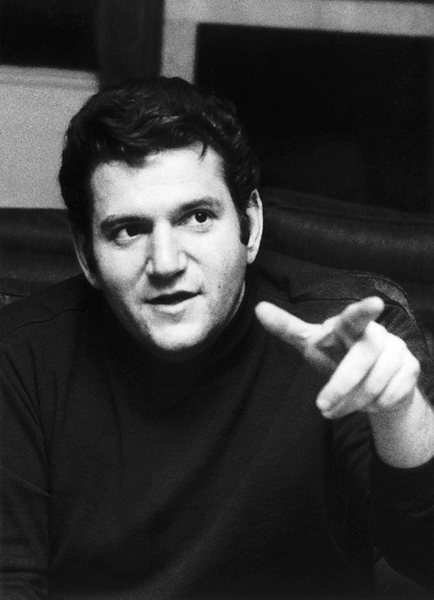

Allen Klein on the other hand was rough and ready. His obituary said of him, that he had the, “Gun rattle of Brooklynese argot, liberally sauced with ripe invective.” He had been called to London to meet John Lennon. The ensuing face-off between Eastman and Klein was akin to tough Brooklyn taking on suave Manhattan: there was only going to be one winner.

In 1967 Allen Klein was driving his car through New York when the news broke that Brian Epstein had died. Klein slapped his steering wheel hard. “I’ve got them, I have fucking got them,” he thought to himself and pushed his foot down harder on the gas pedal. He had met Epstein back in 1964, at the time of the band’s first American tour, and offered to renegotiate the band’s recording deal and get them a much higher royalty rate. In return, he would get 20 percent of the money earned by the higher royalty rate. Epstein took one look at this character with his raw language and disheveled appearance, and showed him the door.

Klein shrugged his big shoulders and went to Plan B, The Rolling Stones. Their manager Andrew Loog Oldham loved hustlers and shakers, mainly because he aspired to that status himself. His favorite film was The Sweet Smell Of Success starring Tony Curtis and Burt Lancaster. He loved the film’s smart language, the clothes, the betrayals. Oldham saw Klein in a similar light and was enthralled.

Mick Jagger recalled, “Andrew sold him to us as a gangster figure, someone outside the establishment. We found that rather attractive.”

Klein read the signs and played his part to a tee. “Andrew liked having me portrayed as this shadowy American.” Klein later said. “That was Andrew. He just created it, that I was like a gangster. He said they’d love it in England.”

Klein had previous. Back in the day he had worked with Sam Cooke and Bobby Darin, and had extracted money from Mafia-owned labels where no one thought money could be extracted. He also liked all things British. Along with The Stones, he also helped out The Animals, The Kinks, The Dave Clark Five and Donovan. For Klein, the road was only leading one way—toward the gates of Beatle Land.

Derek Taylor brought him to Lennon in 1969. The flow of money pouring from Apple had to be stemmed. Tough measures were needed. Phone tough-guy Klein, then. A January meeting was held in a plush London hotel. John and Yoko, Allen Klein. They hit it off well. Lennon warmed to Klein’s background, the lost mother and the time spent in an orphanage all chimed with him. Plus, Klein had done his homework. He knew the best way to a songwriter’s heart is always through his songs.

Klein started telling Lennon about his lyrics and songs he adored. Not obvious numbers that any Joe could have heard, but B-sides and album tracks that few people spoke about. Lennon’s ego lapped it up. Klein may have been a hard-hearted businessman but he was also a music man and in those days the two were not that compatible. Managers managed. They got their acts money and fame. They rarely stopped to like or understand the music they were selling. Klein did and that made him very attractive to Lennon.

The next day, Lennon told his gang that they had a new manager. “Do we?” asked McCartney. After the last year or so, Paul was no longer prepared to follow the leader. That is why he too had been working behind the scenes. When the band had signed a new contract with Brian Epstein, they had actually signed to Epstein’s company NEMS. On Brian’s death his brother Clive had taken over but just two years into the job he wanted out. He announced he wanted to sell NEMS. McCartney phoned his father-in-law to ask for advice. He told him to buy NEMS. Borrow the money required from EMI and then that way you own the company that owns you.

Lennon organized for the band to meet Klein at Apple. George and Ringo followed the leader, and took to Klein, “Because we were all from Liverpool,” George noted, “we favored people who were street people.” McCartney did not trust Klein at all. He felt that the Eastmans would be far more old school, far more transparent than the hustler Klein. The band argued differently. They pointed out that Eastman would be on Paul’s side in whatever negotiations took place.

The gang divided itself and battle lines were drawn up. Things came to a head at a session for the Abbey Road album. It was a Friday night. McCartney arrived early and was playing an instrument when the rest of the band showed up, with Klein in tow. They asked McCartney to sign a contract giving Klein 20 percent. Paul refused. He told them they were a big act—he should get 15 percent. No way, 20 said the others. Only fair for what he was going to do for them. McCartney did not pick up the pen that night.

The band went ahead anyway and ordered Klein to begin shaking up Apple. Out went Ron Kass, Tony Bramwell, Denis O’Dell. In came Klein’s people. An uneasy compromise was also put into place. Klein would look into all the deals to date and uncover all hidden monies, his specialty. The Eastmans would handle all new deals, thus giving the band security on two fronts. It didn’t happen. Within two weeks Eastman and Klein had clashed over important documents. Then in late March, Dick James the director of Northern Songs, the company that owned the Lennon and McCartney catalog, announced he was selling his share to Sir Lew Grade of Associated Television.

And so it went, headache after headache, the band spending days and days and days—and oh such long days—around the table at Apple, arguing over money and management, over lawyers and shares. And they should never have done so for they were musicians. They should have been making music, recording, performing, doing that which all bands must do.

Instead, they spent their time totally out of their depth. In reality, they were far too young to understand the complexities of the money world they were trying to control. They had no real head for business and money. John would later admit, “We were naive enough to let people come between us,” he said. But then added, “But it was happening anyway.”

If the truth be told, it had happened the day John met Yoko really—that was the day the gang began to fall apart. Everything since had been a long and painful death throe. With Lennon off promoting world peace and filled with obsession for Yoko, Paul, George and Ringo all started making solo albums. In April McCartney announced the imminent release of his solo album McCartney. He was furious. Through Klein, Lennon had handed over the tapes of the Get Back sessions to producer Phil Spector. He had gone through them and produced the album, Let It Be.

To McCartney’s disgust, he had added strings, a harp and female backing vocals to McCartney’s major composition “The Long And Winding Road.” Lennon supported Spector the whole way. “The tapes were so lousy and so bad none of us would go near them. They’d been lying around for six months and none of us could face remixing them. But Spector did a fantastic job.”

The legendary producer Phil Spector who Lennon asked to salvage the band’s Get Back session tapes. McCartney was angered by Spector’s treatment of his song “The Long And Winding Road” although the song did go on to win a Grammy award in 1972.

McCartney fired off a letter to Klein and Spector, which began, “In the future no one will be allowed to add to or subtract from a recording of one of my songs without my permission …” He then filled in a questionnaire supplied by Derek Taylor, designed to answer all press inquiries that would accompany his solo album. His answer to the question as to whether The Beatles had broken up was, “Yes, we won’t play together again.”

As soon as the press saw the statement phones started ringing all over the world. John in particular was annoyed. He had split the band up so he wanted the credit. It was kids’ stuff really, but typical of where The Beatles were now at with each other. George agreed. “In that period everybody was getting pissed off at each other for everything … He had that press release, but everybody else had already left the band. That was what pissed John off … It was, ‘Hey, I’ve already left and it’s as if he’s invented it!’”

On April 10, 1970 the headlines arrived. “The Beatles Split Up.” The gang was no more and the game was up. “I absolutely did believe—as millions of others did—that the friendship The Beatles had for each other was a lifesaver for all of us,” Derek Taylor said with typical insight. “I believed that if these people were happy with each other … life was worth living. But we expected too much of them.” These words are so true, but the spirit of the gang would live on, refusing to wither or to die.