After Nihilism, after Technic: Sketches

for a New Philosophical Architecture

Federico Campagna

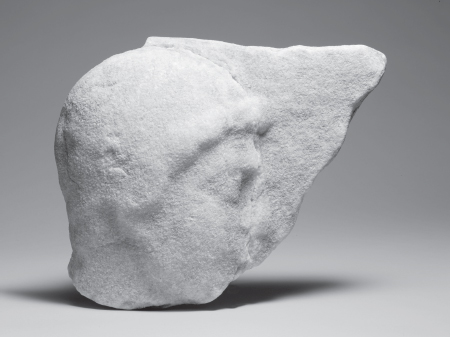

A marble relief fragment from the Late Archaic period shows the profile of an East Greek or Lydian youth (first quarter of fifth century BCE).

Even at the end of the Byzantine era, when Constantinople’s crumbling walls were all that was left of the long-gone splendor of the Roman Empire, the inhabitants of the city would still refer to themselves as Romanoi, “the Romans.” Likewise today, as a new era takes the world by storm, much like the Turkish armies did to Byzantium, we continue to refer to ourselves as the willing or unwilling subjects of capitalism. Yet like the faded insignia of a constitutional monarchy, stat rosa pristina nomine—nothing of the old carnivorous “rose” of capitalism remains but the name. A thin layer of spectacle covers the turgid expansion of a new force, at once much older and much newer than capitalism itself. What can be old and new at the same time? Only a demonic entity is capable of such a logic-bending feat, and indeed the force gnawing at capitalism’s marrow has long been identified as such. Its name is Technic, that which Ernst Jünger called “the chthonian force of the Titans.”

Once subjected to capitalist ideology—and before that, to countless other ideologies—Technic has now surpassed its old master, and it now grinds it beneath its heel. Finally free from any external constraints or directions, absolute Technic has even shed the appearance of its supposed neutrality: to a world struggling out of the desert of nihilism, Technic now imposes a new set of fundamental values, reshaping the ethics and the metaphysics of reality. It won’t be long, if it isn’t too late already, before the kingdom of Technic will have accomplished its total mobilization of the world, down to the deepest corners of the human soul.

But what is Technic? Following Emanuele Severino, we could describe it as the essence of the principle of instrumentality, according to which it is possible to transform things into means to be employed in the pursuit of aims.1 Such a definition of Technic seems to coincide almost perfectly with the definition of humanity typical of Western modernity. According to this view, which Oswald Spengler defined as the “Faustian” spirit, the peculiarity of a human being is exactly his or her ability to transform the world in order to produce complex tools for the pursuit of whatever aims, ad infinitum.2 Within this perspective, Technic appears not as an alienating force, but rather as the enabler of our supposedly “true” human nature. Faustian anthropology and absolute Technic find and justify each other along a tightly stepped minuet.

Unrestrained by any external teleological framework, contemporary Technic has bent its trajectory to compose a perfect circle, setting its own expansion as the world’s ultimate, universal aim. The tiresome refrain that “the medium is the message” returns now as an echo of this profound transformation of means into ends, toward the infinite expansion of the world’s productive apparatus and its ability to endlessly increase itself. As a long period of nihilist destruction begins to fade, the dawn of absolute Technic reclaims for itself a position of full autonomy and universal reach. Crowned Technic bridles the world in order to endlessly expand Technic’s power, for Technic’s sake.

In this new position as the dominant force over the present, Technic’s conceptual grid produces an ontological translation of the world into what Martin Heidegger defined as a “stockpiling of standing-reserves.”3 Under Technic’s watchful sun, no aspect of reality remains untouched by the furious rays of translation: nothing is sacred, as nothing resists the process of fragmentation into discreet linguistic units, perfectly manipulable and definable. If the essence of Technic is instrumentality, then the essence of instrumentality is the hybris of total language.

With predictable irony, the hermeneutic destabilization of reality first announced by Friedrich Nietzsche as nihilism morphs today into the asphyxiating framework of a new, all-reaching metaphysics. However silently beneath the mask of late capitalism, Technic has issued a universal call to order—its own order—following which the whole of reality is expected to present itself as readily available to be linguistically defined, classified, broken into discernible units suitable for purely productive employment. Like that of Osiris, the body of reality is torn apart and sewn back together in the service of Technic. Here lies the true source of Technic’s power, as its demonic roots stretch into the archetypal depths of mythology.

Differently from the age of capitalism, however, there is no longer any particular social class that is expected to benefit from such Faustian reassembling of reality. Even the so-called one percent is but the contemporary equivalent of the inner circle of a Carthaginian cult of Baal: standing, wearing clay masks sporting a large grin, watching their own world and that of their children destroyed by the fire of the new, triumphant god.

If we accept the transitional nature of the recent nihilistic phase—similar to the past nihilisms of the Sophists, of Alexandrian Hellenism, and of the Baroque—it appears clearer how the most crucial response to Technic’s assault should take place beneath the field of politics or economics. Technic’s total mobilization of reality began at a metaphysical and ethical level. Any attempt at overturning this epochal shift should reach to such an abyss, and any effective counterassault should forego postmodern timidity in favor of affirming metaphysical foundations and ethical values. This possible counterassault could be described as the creation of a new architecture of values, stretching from the gates of Being to the core of ethical choices. What might a basic outline of a possible, alternative plan of fundamental construction look like?

Such a sketch must start from (ultra)metaphysical considerations, since it is at this depth that contemporary Technic has produced its most crucial breach. As epitomized by language, Technic proposes a metaphysical view of reality according to which nothing lies beyond the reach of translation. According to Technic, there is no “outside” to language, no dimension that cannot at least potentially be reduced to precise and distinct units of meaning and production. Conversely, our experience of the world suggests that something lies beyond the reach of language. The very mystery of existence, the impenetrable fact of reality, however unreachable it may be by our discursive understanding, can awaken us to the undoubtable truth of Being. While individual beings remain objects of phenomenological observation, of metaphysical investigation and painful doubt, the mere fact of existence glimmers as an ultra-metaphysical truth. Its unmistakable darkness, its “mereness”—to borrow Wallace Stevens’s intuition—shines clearer than any Faustian project of total linguistic “unveiling” (aletheia) as proof of its presence beyond the horizon of language. Awaking to Being means facing a dark, absolute truth that shapes and limits the field of particular truths referred to as individual beings.

On this basis, the first step into a new architecture of values comes in the setting of limits. Negatively drawn out of the darkness of Being, the field of linguistic translation—and thus, of action—emerges as a game shaped by the specific limit of the board over which it takes place. One step beyond the edge of metaphysics, and the horse falls off the edge of the chessboard—and yet it is just that abyss that makes the game possible.

While the ultra-metaphysical darkness of Being is a truth to which we can awake—doubtless and speechless—approaching the ever-shifting shapes traversing the game board of language requires a further effort: faith. Against a common misconception, the issue of faith arises not in our relationship to Being, but in our relationship to the singular linguistic entities that we carve out as material, immaterial, or conceptual constructs. Faith is the trajectory produced by will, and it bridges the abyss of doubt over the field of the unveilable. This has nothing to do with awakening to the un-unveilable Being. Faith always confesses its own weakness, its dependence on will, and ultimately its own arbitrariness.

And yet, faith features as the second, crucial element to this new architecture of values. The mysterious objectivity of Being is complemented by the arbitrary subjectivity of faith. The realm of faith is that of metaphysics, the land of beings, the field of culture, the space of action.

One always talks about one’s own, singular, arbitrary faith. Its origin is the individual’s will and arbitrariness, although the foundations for action that it provides can be adopted by a virtually ecumenical community. In this case, it is my faith that I propose as a second force alongside the awaking to Being: precisely, my faith in the value of life. Nothing proves, or even suggests, the intrinsic value of life. Life’s value is not objective, and can only be affirmed as the product of an individual’s act of faith.

If we consider Being as an objective, constitutive force of this new architecture—similar to gravity for traditional architecture—my faith in the value of life resembles the architect’s arbitrary destination of a building: two unequal forces, equally intertwined. Similar to traditional architecture, this interplay between arbitrariness and objectivity unfolds here through a process of craftsmanship—through Technic. Rather than assaulting reality as an autonomous agent, however, Technic features within this architecture as a force that is limited by Being’s ultra-metaphysical presence, and functionally submitted to the set of worthy aims produced by faith in life. The rebellious servant is brought back under its master, although this time mastery is bestowed not upon a rigid and totalizing ideology, but upon an arbitrary faith that is aware both of its weakness and the limits of its metaphysical reach.

Once reduced to docility, Technic’s unfolding is assigned a rhythm by the combined forces of Being and faith—structuring it from the outside and from the inside, respectively. Action and language take on a rhythm characterized at once by lightness and heaviness.

Lightness, in the face of the fabric of reality. Different from both nihilism’s desertifying gaze and from Technic’s cage of total language, the fact of reality is considered here in its ultra-metaphysical qualities: it is Being that breathes pneuma into the world and into what exceeds it, while our linguistic actions have no role in keeping together the fabric of reality. The nausea produced by absolute freedom was only a moment of vertigo, followed by the realization that not everything is at stake, that we are not the makers of the universe.

Yet freedom still retains a position of heavy responsibility, weighing on our conduct throughout our lives. Although irresponsible toward the very existence of reality, our actions and our technical manipulation of language remain fully responsible for the maintenance of our faith in the value of life. If there are no objective gods safeguarding life, if there is no Zeus Xenios looking after the rights of the supplicants, it is only the discipline of our own will that can create a new mythology of emancipation and a practice of arete as the beautiful reproduction of faith through action.

Ethics is thus limited by Being’s ultra-metaphysical presence, at the edge of which it awakens, remaining powerful within such limits. Only its responsibility to maintain faith in life closes the harmony that transforms its unfolding from noise to music, its flowing from frenzy to dance. It is only the interplay of the forces of Being and faith that empower and lead the hands that will realize our new architecture of values. First toward the building of a defensive wall against Technic’s assault, then toward the construction of mythological and cultural weapons to lead our counterassault. And finally, toward the establishment of an inhabitable “cave of the nymphs,” an oasis of limit and freedom, where the chorus faithfully sings for its own glory, and Apollo benignly looks on from beyond.

Federico Campagna is a writer and philosopher based in London.