—LIONEL TERRAY

—LIONEL TERRAY

On the third of March we crossed our final pass, the Taksindu Banyang, at 10,000 feet. Throughout our eastward journey the country had grown in vastness and depth. Here the bottom seemed to drop out and a whole complex of ridges and hillsides fell toward the silent thread of river a mile below. “That’s the Dudh Kosi, the Milky River,” Norm said. “We’ll cross it tomorrow.” His face showed his pleasure in having once again, after several years, come home. This was the place he knew, the Solu Khumbu, the home of the Sherpas. That moving thin line of white so far below was a raging torrent, the largest we would have to cross. It was no harder to believe that than to believe that we could possibly descend to it in a day. The thought of the climb back out again, months later, weak and worn, flashed through my mind and was quickly dismissed.

A sweat-soaked porter passed by under two boxes of oxygen bottles, a 145-pound load and a tough way to make an extra dollar. Norm and I started down through the forests, looking down on the grey and brown tree tops, intricately patterned in their winter nakedness. White islands of blossoming magnolias were beacons in their stark setting and reminded me of dogwood in the Ozark spring. We camped that night on a shelf a short distance below the pass. The moon shone on a haze of rising mist and the smoke of many fires. Beyond the trees, the world spilled into a silvery moonlit cloud on which the ridgetops floated.

Before the night was half begun, the coughing and talking of the porters began, followed too soon by Danu’s banging a spoon against a kitchen pan. The crew staggered from the comfort of tents into the damp predawn chill and stood shivering about the sagging metal table. By lantern light we groped for tea, cocoa water, and Metrecal cookies to plaster peanut butter on. With packs and umbrellas we were off, coasting down toward a river hidden in the darkness below. As the sun rose we broke out of the forest, crossed steep tilled fields past thatched farmhouses, and felt the freshness of the new sun give way to the familiar heat of mid-morning until relief came in the humid shade of the jungle. The trail descended in steps made of rocks and tree roots that trapped the dark humus of old leaves; the smell of moist earth was freed by our slipping feet. Ahead in the clearing, smoke rose from the fire. Danu was there with breakfast. The deep rumble of the Dudh Kosi carried easily through the one remaining thicket.

The warmth of the sun, topping off a full breakfast, breeds a certain inertia, at least in those pushing middle age and having a streak of laziness in them, so I lay in the sun shirtless, my face covered. The world was held at a distance; murmuring voices, buzzing flies, the grass tickling the backs of my legs, the momentum of life at a complete standstill. Thoughts floated lazily, as boundless as the clouds, only to be intruded upon by the sound of Jake’s voice:

“Can you reach that little nubbin up to the right? It might take one fingernail.” I peered out from under my hat, squinting into the brightness. Barry was glued mysteriously to a wall on the huge boulder at the lower end of the clearing. I watched, wanting to remain uninvolved, as his fingers groped blindly for a handhold, creeping across the smooth granite with sensitive movements of a pianist. At last his hand paused, on something? Then almost magically his body straightened, smoothly and delicately, the edge of his boot biting on a tiny flake and holding. Jake watched quietly, the serious set of his mouth belied by the relaxed grin in his eyes. Then he took to the slab, fingers dancing over the rock, boot edges clinging to imperceptible exfoliations, polishing the rough edges left by Barry’s pioneering performance. They were both fine climbers.

Bouldering, when we could find the opportunity, provided a refreshing interlude. It reminded us we were climbers, not merely walkers and that soon we would be called upon to put our climbing to the test. For now, each brief pitch was a puzzle. Following Barry’s and Jake’s lead, each of us tried to solve it. Dick’s arms had never been over-strong for his weight; his power was in his legs. As a result he had developed a fluidness of motion over the years, and his studied control was beautiful to see as he followed after Jake. In contrast, Unsoeld attacked the problem with the same energetic flair with which he faced all challenges, achieving feats of gymnastic contortion with the grunts and groans of a professional wrestler. Before long he was spread-eagled horizontally across the wall, one hand high above, the other pressing downward against smooth rock several inches below his feet. In the end he got there, at the price of an audience completely drained by his skillful brinkmanship. I followed monkey-style, weight too much on my wiry arms and fingers. Will had been studying the rock, jaw muscles contracting as, like a chess player, he plotted each move in advance. Then he attacked with a determination that seemed to say to the rock, “Either I get up or you come down.” Our ice climbers, Jim and Lute, gave it a try, mumbling about the beauties of cutting steps up steep ice. Pownall, a superb rock climber, didn’t join the game—and even deprived himself of the greater pleasure of being a heckling spectator.

It was slow going the day we moved from Pheriche to Lobuje, climbing the 2,000-foot terminal moraine of the Khumbu Glacier. We were new to the altitude and felt it. At about 16,000 feet, Barry and Jake found a boulder and several people were sitting sluggishly on the hillside looking at it. Altitude itself, I soon discovered, was the challenge in the 15-foot crack Barry had pioneered. Tackling the pitch with naïve enthusiasm, I found myself folding over on the flat summit, prostrate and panting. What a fantastic difference, climbing from 16,000 feet to 16,015! It certainly added a new dimension to bouldering. Porters would come by, set down their loads to watch our antics, then saddle up and shuffle on. One youngster stayed, grinning. We grinned back. “You try?” we asked. Shyly, he came down to the base of the rock, wearing a pair of rotting boots. He attacked the sharp, narrow crack with a graceless gusto which carried him halfway to the top before he fell off. He laughed, embarrassed, and went at it again, and again. Finally, in frustration, he sat down and removed his boots. As we watched in pained amazement he curled his toes into the knife-edged crack and scampered to the top. He grinned with pride at our cries of “Shabash, well done!” and our predictions about his future as a great high-altitude Sherpa.

We put so many routes up the Lobuje Boulder that there was talk of publishing a guidebook. Coated by a fresh fall of snow, the boulder provided a good training ground for our Sherpas in preparation for the West Ridge. They greeted the practice sessions as children might, jesting, exclaiming, and a little fearful. Uproarious laughter followed when one of them slipped from his holds to dangle at the end of the rope. Many of them climbed with a primitive naturalness that was enviable. It was a universal game.

Yet these scrambles were more than just games for exuberant overripe youth. They were preparation, in a way, for the adulthood that was waiting ahead. Each rock puzzle was a test, though not in a mountaineering sense. Nothing so difficult existed on Everest, on terrain already so well known. This was fortunate, for cold and altitude would make such rock unclimbable. The measure was more of the man than of his climbing ability. Though the performance of others might provide some yardstick, each man faced a solitary challenge. Whether you succeeded or failed on any given pitch, the revelation was in how you faced the challenge, and how Barry did, and Dick and Will. You watched silently, noting the ability of a man to laugh at his own awkwardness. Impatience, self-castigation, the quality rather than the quantity of determination, unreasoning perseverance or reasoning self-appraisal. Impressions were formed, evaluations made and filed away. Competition may have been a part of these games, but if so, it was purely of an individual’s own making. There was nothing inherently competitive in climbing from the bottom to the top of a boulder any more than in running the four-minute mile; you were competing only with yourself. In this bouldering seemed to differ from the effort for which it helped prepare. These scrambles were not Everest in miniature; on the mountain competition would almost be forced upon us for two reasons: not everyone would get to the top; all of us wanted to.

Norm broached the question of attitudes toward the summit one evening after dinner. “I’m curious about one thing,” he said. “If we’re really honest with ourselves, how many of us have real strong hopes, and expect to get to the summit?”

Will Siri scanned the bodies crowded inside the tent. “How many people are there on the team?” he asked in reply.

“Lester, I didn’t see your hand up there,” said Norm, smiling at our emphatically non-mountaineering psychologist. “But I’m sure that we all know that only a certain number will be able to make it. That’s all there is to it logistically; as many as possible, but there are limitations.”

“I don’t think you’ve got to worry too much about it,” Big Jim replied. “I think the whole team thinks that as long as two men, as long as somebody, gets to the summit, goddammit, that’s the important thing.”

The only important thing? What about the individual dreams? How do you reconcile the personal ambitions of nineteen climbers with the notion of a group goal which if achieved by some is thereby achieved by all? Nineteen prima donnas could yield a highly explosive mixture. Perhaps appreciation of this fact was enough to prevent detonation. Or was it the realization that no man’s hopes could be fulfilled outside the group’s goal, that no one could climb Everest alone?

Perhaps a team devoted solely to the expedition objective would be optimal, a group all of whom could say, “It’s only important that someone gets to the top. I’ll do all I can to get him there.” Such a philosophy would certainly produce a well-meshed effort. But we were not such a group, and I doubt that such a group would have the same intensity of drive as that attained by a team of personally motivated individuals. With group motivation one extreme, and competitive uncompromising personal desire the other, we fell somewhere between as a team. Two issues helped to clarify where the balance lay: the question of Sherpas on the summit team and the question of West Ridge.

“I think we should also think of what part the Sherpas will play in the final assault,” Norm suggested. “I’d like to get some of your reactions and points of view on Sherpas going for the summit. But it should be clear to all that this will diminish each individual’s chance to be a member of a summit team.”

“Well, let’s ask then,” Will said, “if anyone feels Sahibs should have the first crack at the summit if they are able to do so, or whether it should be Sherpa-Sahib teams.”

“I think personally Sahibs have the first crack at it, if they are healthy enough to do it,” Dave Dingman said.

“At least,” said Big Jim, “the Sahib should lead the rope.”

“Well, at least be on it,” I added.

“Many of these Sherpas have been to the summit of big peaks before; there is no question of their ability,” Norman said. “We will strengthen our team if we do figure on Sherpas as members of the climbing team. I think it will strengthen us tremendously.”

“If we deny them the opportunity to get to the summit and some of them are able to do so, I think we would make ourselves exceedingly unpopular with the Sherpas,” Will said. “Besides, I think we may be overestimating the number of people we’re going to put on the summit. Everest is still a high peak and we’re not going to be racing everybody up the mountain. I think the chances of getting everyone to the summit who would like now to get to the summit are very, very remote. There’s one other thing, too. You may not appreciate this yet, but once you start climbing with the Sherpas they’ll become far more a part of the team, and friends, than they are on the approach march. There will be less distinction between Sahib and Sherpa.”

Jimmy Roberts offered a bit of British logic. “Yes, I think technically now, the Sherpas are quite capable of reaching the summit of Everest, possibly without Sahibs. They like a Sahib along. I’d say there was no necessity to make a political thing of insuring that a Sherpa gets to the summit. I think—just let things take their own course. I think you’ll find that one or two Sherpas will reach the summit. I would say that if one Sherpa has got up, and there are two equally fit—a Sahib and a Sherpa, then let the Sahib go. They’ve had a lot more work to do on the preparation. They deserve it more.”

“You know, of course,” Norm said, “that the West Ridge will also diminish the number of people who get to the summit. You have to be aware of that.”

“I think the probability of that is extremely high,” I added. “Presuming that you don’t even succeed on the West Ridge, as few as two people could end up climbing the mountain.”

“Well, now let’s discuss this for a minute,” Norm said. “How do you feel about it? Is this fair in a way, to lessen the chances of a certain number of people to get to the top by tackling the West Ridge? Then a lot of guys who are counting heavily on the summit won’t have a chance.”

Big Jim expressed what most of us thought. “I think that for the good of the Expedition we should have an objective other than just the South Col and the quantity of people on the summit. We should have a new route.”

“I would second Jim’s point,” Will said. This was followed by many nods of agreement. As things stood now, still far from the mountain, there appeared to be a mature balance between personal ambitions and expedition goals.

Whatever weight personal ambition had in this balance, there was one thing that made competition unnecessary. It pertained less to summit hopes than to the myriad challenges of productive day-to-day survival on the mountain. It was the simply lonely question asked in self-appraisal on the boulder. Can I?

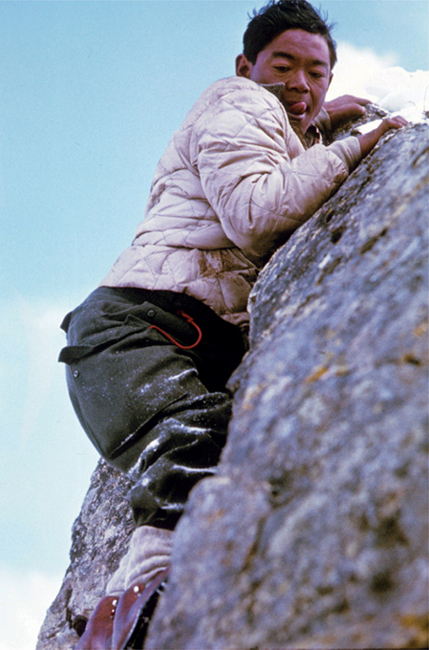

Sherpa bouldering before Lobuje (Photo by Lute Jerstad)

Young Sherpani (Photo by Gil Roberts)

Inside a stupa gateway, looking up and out (Photo by Richard M. Emerson)

One of many waterfalls encountered on the trek in (Photo by Richard M. Emerson)

Rhododendrons in the rain (Photo by James Lester)

The camp at Puijan (Photo by James Lester)