—SIR FRANCIS YOUNGHUSBAND

—SIR FRANCIS YOUNGHUSBAND

On April 3 Dick and I slogged up the Cwm to set up housekeeping at Advance Base. The long, gradual stroll seemed interminable as we wandered back and forth between crevasses. We paused often to sit on our packs and nibble a bit of fruitcake, and to look at the tiny figures of the Sherpas far ahead.

“God, the camp must be another couple of miles,” Dick said. “I don’t think we’ll ever get there.”

Inside, I wearily agreed, but I couldn’t let Dick get discouraged. “No, it’s just over that rise, below those ice cliffs where the Swiss had theirs.” I willed the camp to be there.

It seemed almost too familiar after all the pictures. Familiar, except for the scale of things: Everest, bulking huge above the West Shoulder, Lhotse, foreshortened at the head of the Cwm, the wall of Nuptse soaring a vertical mile above our heads, its glassy slabs of ice shimmering in the sunlight. The Valley of Silence, up which we plodded, appeared almost level, but our labor belied the illusion. Heat, reflected from the surrounding walls, converged at the valley floor. I felt trapped in a gigantic reflector oven. My mind sought some distraction—a poem, plans for the West Ridge, thoughts of home—but heat drove thought away. I found myself counting steps. One foot, then another. Ten steps, and a drop of sweat dripped from the end of my nose; another ten, nope, only made nine before the next drip dropped—drop dripped? Try for ten. Nine again, damn it. Is Emerson talking to himself up there? He must be completely fuzzed by the altitude. But still, where does he get the wind to talk? All mine’s used up just breathing.

In the Western Cwm (Photo by Norman G. Dyhrenfurth)

Not till the homeward journey did Dick confess that he wasn’t talking to himself but to the tape recorder hidden in his vest. His demeanor, though not an act, was nevertheless designed to test the nature of my response, which, committed to tape, became a part of his sociological study.

At 21,350 feet, midway up the Cwm, Advance Base was higher than any point on the North American continent. This was the jumping-off point for the two routes. From here we would go up-Cwm to the base of the Lhotse Face and the South Col, or would take “the one less travelled by.” We could look straight up to the point where the West Shoulder bumped against the mountain itself, against the West Ridge.

According to plan the reconnaissance of the West Ridge would have first priority once Advance Base was established. The equipment for the recon accumulated there slowly, since we had temporarily outrun our line of supply.

“One big problem,” I wrote home, “has been with our Sherpas. Perhaps it is the big, fat, rich American image, and the fact that they have been at this too many years, but it is much like a labor union trying to put on the squeeze. It began four or five days ago at Base when they requested a second sleeping bag (the Indians had supplied two kapok bags last year). Instead of saying flatly no, that one Bauer bag was adequate (which it is), we agreed to pay them twenty-five rupees a month.

Next we get to Camp 1 to discover that many of the loads coming up are 35-40 pounds, not the 50 planned for, and we cannot get our Sherpas to carry full 50-pound loads to Advance Base. This all adds up to more carries, loss of time, and a diminution in chances of success, at least on the West Ridge, if not the Col. Willi tried to put four oxygen bottles (52 pounds) on one man to Advance Base but was forced to compromise because of new snow (3 inches) and a ‘difficult track, Sahib.’ The next day I fell heir to the job and went through the same nonsense (‘difficult balance on log bridges with heavy load, Sahib’) but finally got a carry up here that approached 50 pounds per man, with much grumbling and unhappiness on the part of all, especially me, for I find such a role not delectable.”

We sat at Advance Base, forced into a one- or two-day delay in starting the recon. I hovered protectively over the pile growing slowly outside the mess tent, taking repeated inventories—pickets, ice screws, fixed rope, one four-man tent, and twelve oxygen bottles—and mentally figuring deficits. All we needed were the stoves and three food boxes. Big Jim, Lute, and Dick Pownall eyed those forbidden goods enviously. As the pile grew, so did their discontent, a discontent derived from impatience to begin the buildup of the Lhotse Face, and nurtured by the oblivious enthusiasm with which I sequestered the incoming supplies. This was the first sign of a conflict that was inevitable between the two routes. From now on we would be competing for manpower and equipment to accomplish our separate goals.

The basis for conflict could be sensed long before, almost with the first separation into two teams. The growing enthusiasm of one team for its route heightened awareness in the other of the competition necessary to fulfill its own needs. As a result opinions were stated more forcefully—and less charitably—than they were felt. Thus the original separation born of personal desire was accentuated by an interaction in which each team found the other increasingly more vigorous and dogmatic in its own defense. The thing that saved it was that usually we were aware we overstated our cases. Though in group discussion I might be outspoken in defense of the West Ridge, in the privacy of my tent I could readily admit my understanding of the South Coler’s point of view and express my doubts about the West Ridge. Others must have faced the same problem of achieving compatibility between their goals and that which they knew was just. The value and rightness of one route over another was solely a matter of where each man’s hopes and ambitions lay. To avoid conflict was impossible. How constructively such conflict might be resolved would depend on the maturity and self-control of the individuals involved, and on their ability to compromise.

At Thyangboche we had chosen the team of four for the recon; now Dick was not to be a part of it. Each meal he ate refused to stay down. Weak simply from lack of food, he headed dejectedly down to Base to recover. From my own intense anticipation of the coming adventure I could imagine his disappointment. Jake’s death left Barry or Dave, who were at Camp 1, to fill the empty hole.

“Who will it be, Willi?”

“Dave. Neither of them is feeling too well at the moment. I’d rather save Barry for the buildup. I have the feeling we’d be better off using Dave early since I’m not sure how enthusiastic he is for the Ridge since Jake’s death.”

Dave came up from Camp 1, not overjoyed at having to climb while feeling so poorly. On the following day, April 7, Barrel, our seven Sherpas, and I headed up to establish camp at the Dump site. Dave would rest the day at Advance Base and come up with Willi early the next morning. It was a blustery day, and windswept snow scoured the Cwm. Even old Tashi wanted to turn back at the bottom of the fixed rope, but we were too close to the Dump.

“Just a couple of miles more, Tashi,” I said, and his eyes lit as he heard the Sherpa answer to our own frequent questions during the approach march.

Willi and Dave showed up on schedule. Unfortunately, starting at 6 AM, they had encountered not only wind, but also the bitterness of early morning cold. When they poured puffing into the tent, Willi’s hands were beyond his feeling them, but their effect on my bare stomach was something else again. Dave was just plain tired. Our plan had been to push on to the Shoulder to establish camp and begin the reconnaissance, but it seemed like doubtful weather for climbing. As things developed the decision was not for us to make. From the kitchen which was in the Sherpa tent, no sound emanated.

Advanced Base Camp (Camp 2) (Photo by Maynard Miller)

Near Dump Camp on the West Shoulder (Photo by Willi Unsoeld)

It was after ten when Tashi appeared with morning tea. “Passang Temba headache, Sahib,” he reported. Caused by the rattling of wind-whipped tent?

Another hour and it was obvious that we had been stalemated. Had wind and Sahib ambition permitted, there were not enough daylight hours remaining for a carry to the Ridge. We sent the Sherpas down to Advance Base to save food. They would return empty in the morning to make the carry, weather permitting. Otherwise, we’d come down. We also resolved to keep possession of our own kitchen in the future. The rest of the day we ate peanut butter and talked.

April 9 was clear and calm. The seven Sherpas pulled in just as Willi and I started breaking the trail toward the fixed ropes. Once around the icy corner we were in the open, switchbacking up steep slopes. The snow was firm, occasionally icy. At least none of that knee-to-waist–deep stuff we had labored through on Masherbrum—one fringe benefit of Everest winds. Willi’s feet flailed steps in the snow as he steamed ahead. Coming behind on the rope was breathtaking. Each change of direction required fresh gymnastics, flipping the rope, collecting coils, running to turn the corners, then gasping for air as Willi moved steadily forward.

“Dammit, Willi, what are you trying to do?”

He smiled back, thought for a moment, and replied, “Just testing you.”

“For what?”

“Bigger things.”

When the snow is hard and crampons grip well, it is easier to go first than second. You can move at a continuous pace, zigzagging up the slope, while your companion, forced to keep the slack out of the rope, follows erratically after. Willi was going all out, and the figures of the others dwindled below, but after a time it became easier to hold the pace. Finally, as we neared 23,000 feet, Willi stopped, panting. “Let’s trade off for awhile.”

Now Willi suffered the inconvenience of coming second; the rope became taut behind as we proceeded. With almost impersonal detachment I observed this stretching of my limits, filing the information away for the future and reveling in the pleasure of the effort.

By 4 PM we were still below the West Shoulder, which was hidden by falling snow. The late hour, weariness, and sheer boredom with putting one foot in front of the other all encouraged a decision to stop. Our search for a tent platform was frustrated by the flat light that made it impossible to gauge the angle of the slope. We dumped our loads below the bergschrund and began hacking out a tent platform. Dave and Barrel arrived, slipped out of their packs and sat down on top of them. We thanked the Sherpas, promising them a day’s rest for their truly long hard carry, a promise that added to the impatience of the South Colers. With only a couple of hours of light remaining, the Sherpas hurriedly departed for Advance Base. Our four-man tent was soon erected. Four people with gear could barely be accommodated crosswise. Cooking would have to be done in the vestibule. I chose the spot nearest the kitchen, determined that we should fare better than on the deadly diet of Pong. As I unleashed my latent culinary creativity, the Old Guide sat back enjoying the unaccustomed luxury of being waited on.

Stuffed with curried-ketchup-covered shrimp and rice we prepared for sleep. Dutifully filling in our diaries, another part of Emerson’s sociological study, I came to the line beginning, “Tomorrow, if possible, I should; will; would like to—” I scratched the last two choices and filled in the blank, “Tomorrow, if possible, I will survey the first step.”

Now, at 23,800 feet we were to sample the benefits of sleeping oxygen. Feeling exceedingly healthy after our race, Willi and I viewed the use of oxygen more as a game than a useful necessity. Still there was pleasure in the status symbol, for now we were joining the Big League as high-altitude Everesters. Add curiosity, the challenge of a new experience, and the realization that ultimately it would make a difference, and we were hooked. For me, too, there was the question of how all the gear I had labored so long over was going to work. Two yellow cylinders were hauled inside, like fish from the frozen sea—one for Dave and Barrel, one for Willi and me. I explained their use with an aura of confidence to conceal that I had never slept on oxygen before, either. A liter per minute oxygen flow was split by a plastic T to be shared by two, reminiscent of a fine old Cole Porter song. Barry and Dave slid into their polyethylene sleeping masks and with disgusting ease were soon asleep. Meanwhile, Willi and I lay awake savoring the new sensation.

“It’s kind of warm inside this thing, Willi.”

“Yes, I’m suffocating,” he replied, ripping the mask off, gasping for air.

“I think I could swim in mine, but the darn thing’s overflowing into my sleeping bag.”

Finally we achieved some sense of satisfaction by dispensing with the mask and holding the end of the hose beneath our noses, sniffing oxygen and trusting some unconscious instinct to hold the proper relation between hose and nose as we slept. I dozed, then awoke, searching for the end of the hose in the innards of my well-oxygenated sleeping-bag. Enough of that. I plugged my climbing mask into the T. That mask would be comfortable. But sleep didn’t come. No oxygen. The flow-indicator on the mask delivery tube provided enough resistance to shunt the entire supply to Willi, who was now sleeping peacefully with the hose jammed delicately into one nostril. Then a sudden surge of gas as Willi’s nose plugged up and I acquired the total flow. I slept, he woke, and so it went for several nights until we finally made our peace with the plastic aquariums. Eventually they provided all the psychological security and womblike warmth any fetus could desire.

The dewy night was followed by an even dewier awakening. As the sun hit the tent, the frost which had condensed on the inner liner began to liquefy. We could lie in our bags watching the drops form and creep to the center of the flat roof top. From the growing pool rain began to fall on the captive audience below.

The effort of cooking and dressing is breathlessly exhausting at high altitude, and even the simplest task is terribly time consuming. But that first day we set a new record—it took us five hours, not owing to altitude so much as just plain chaos. I had wakened to find myself shoved into the vestibule, wrapped cozily around a can of peanut butter. The place looked as if it had been stirred by a power mixer. The four of us were just the beginning. Air mattresses, sleeping bags, oxygen bottles, down parkas, anoraks, reindeer boots, overboots, diaries, first-aid kits, radio, were all well mixed. I hung in the vestibule, brewing soup, while the others tried to dodge the interior monsoon.

“Has anyone seen my other rag sock?” “No, that one’s mine—I think.”

Once shod, we emerged into the white open spaces to rope up—Willi and Dave, Barrel and me. That went all right. Crampons on, then oxygen. We’d be using it for climbing from here up. It was strange and new; screwing in regulators, hooking on delivery tubes, valves open, flow at two liters per minute.

Finally at noon we were off into the fog, headed toward the crest of the West Shoulder for the long-anticipated view. Here there was no question that oxygen made a difference; climbing was a delight. There was a little extra spring in the step, a reserve of energy and alertness to meet the unexpected. Best of all there was freedom to think about more than the alternate plod-pant-plod, with ten breaths per plod; there was freedom to enjoy the view, and to have thoughts to be alone with.

I was very much aware of the rubber mask on my face because I had designed it. On Masherbrum our single attempt to use oxygen ended because of the effort required to breathe through the masks. That same summer Gombu and two Indian companions were turned back high on Everest when they couldn’t remove ice that had formed on the breathing valves of similar sets. The same type of mask had got the British and Swiss to the top of Everest, but in ideal weather. The idea for a far simpler and more reliable mask took shape in my mind during my research on respiration. Fred Maytag’s enthusiasm brought it to reality. His company was more accustomed to manufacturing washing machines than high-altitude oxygen masks, but members of the research division spent many extra hours creating a mold which permitted the entire unit to be made as a single piece of rubber. The result was a mask with one valve instead of six. It could be de-iced by simply squeezing the rubber breathing cone with a mittened hand. Though climbing was one adventure Fred Maytag had not tasted, he understood it and enjoyed being part of our undertaking. He died of cancer three months before the expedition departed.

Cornice and Tom Hornbein on the crest of the West Shoulder (Photo by Willi Unsoeld)

The mask fit comfortably, even around a nose like mine; the goggles didn’t fog from my breath. I watched the oxygen bladder expand and contract with each breath, fascinated by its motion. I consciously overbreathed to accentuate the movement. Suddenly, I felt the rope come tight as Barrel shouted breathlessly: “Slow down, Tom!” He was having trouble getting synchronized with his oxygen. In my fascination with the equipment, my pace had increased considerably, gradually narrowing the gap to Willi and Dave, who had started earlier. Willi, looking back, saw us coming. “Aha,” he thought. “Hornbein’s trying to beat me to the Shoulder.” He brought Dave up to him. “Let me check your flow, Dave,” he said, unobtrusively turning Dave’s regulator to a full flow of four liters per minute, and off they went.

Unaware of the competition I had provoked, I paused and brought Barrel up to me. After checking his oxygen equipment, I suggested that he set the pace. Ahead, Willi’s feet flailed like pile drivers into the snow. The gap between the two ropes steadily widened. What drive, I thought, but what’s his hurry? What’s he trying to prove and who to? I’d never climbed with anyone so intensely competitive. I wondered if the competition was more than just a game, how much it accounted for his tireless drive, his choice of route.

As essentially a noncompetitor myself, I could not say. Yet I was lured into the simple childlike fun of the game. Could I keep up with Unsoeld, whose power on Masherbrum I too well recalled? I thought back to the day nearly three years before when I was toiling uphill at 23,000 feet, heavily laden.

Willi, starting an hour later had steamed past me under the burden of a huge army rucksack.

“Can I take your pack, Tom?” he had shouted from fifty yards ahead.

“No thanks, Willi,” I had answered, sagging to the snow, “I’ll die first.”

The game he lured me into now was rather ridiculous, as Dick pointed out later, when Willi, with unnecessary relish, described how we had tried to run each other into the ground. Though the game could tell me I might have the steam to keep up with him, it left untouched the more basic question of my relationship with the mountain and myself.

Willi and Dave were sitting nonchalantly on their packs staring into blank nothingness when Barrel and I joined them. For the next three hours we all sat transfixed, as the mists played ethereal games, parting to reveal tantalizing glimpses of what we had come to see. All around us was a confusion of vignettes as momentary rifts in the curtain unveiled the dim outline of the North Col, or of improbable bastions, belonging presumably to the West Ridge, or of rock floating free, fantastically high above. During the course of the afternoon, we must have glimpsed most of it, but only piecemeal, as isolated bits of a puzzle which seemed fearsomely greater than the sum of all its parts—a jumble of black, snow-etched walls and arêtes that ended nowhere.

After waiting in vain for the unveiling of all we’d long anticipated in our dreams, we returned at four, chilled and snowed-upon, to the chaos of our tent. There was little to cheer about but a lot to anticipate. If only the mountain could be divested of its modesty. A reconnaissance is a hard chore to perform if you can’t see anything. Not deterred by our lack of success, I closed my diary that day with: “Tomorrow, if possible, I will go above the first step.”

On the 11th we got away an hour earlier. At the Shoulder the mountain waited, fully assembled. The cloud cauldron of the great South Face boiled, accentuating the black, twisting harshness of the West Ridge. We stared. Yesterday’s fragments had not exaggerated. Our eyes climbed a mile of sloping sedimentary shingles, black rock, yellow rock, grey rock, to the summit. The North Col was a thousand feet below us across this vast glacier amphitheatre. As we stood where man had never stood before, we could look back into history. All the British attempts of the ’twenties and ’thirties had approached from the Rongbuk Glacier, over that Col, on to that North Face. The Great Couloir, Norton, Smythe, Shipton, Wager, Harris, Odell, our boyhood heroes. And there against the sky along the North Ridge, Mallory’s steps.

Everest was his more than any other man’s. In 1924, as he approached the mountain from which he was not to descend, he had written: “Still the conquest of the mountain is the great thing, and the whole plan is mine and my part will be a sufficiently interesting one and will give me, perhaps, the best chance of all of getting to the top. It is almost unthinkable with this plan that I shan’t get to the top; I can’t see myself coming down defeated.” This was the legacy we now looked upon. Our Ridge looked formidable. Once again the fear was there, and with the fear, the challenge: but how?

“That must be Hornbein’s Couloir over there,” Barrel said.

“You’re right. I think it is.” I replied.

“It’s a long way over, Tom,” said Willi.

“It sure is,” I said. “I’m not even sure how to get into it unless we can traverse from here.”

“How about that crack diagonally up through the cliff, just left of where the Shoulder meets the Ridge?” Dave asked.

“Yes, that looks possible,” Willi agreed. “From there we can either cross to Horn-bein’s Couloir, if we have to, or cut back up Jake’s to gain the West Ridge above the first step.”

“Sounds reasonable,” I said. “But those cliffs overhanging Jake’s Couloir don’t look too inviting.”

“Not without a lot of preparation,” Willi said. “But it’s an awful lot closer than that avalanche gully of yours. That’s a couple of miles over there and we’re not even sure it cuts through the Yellow Band.”

“I don’t see any signs of avalanche from it, though,” I replied.

“No, but just wait till it snows,” Willi said.

The plan was for Willi and me to try to reach Hornbein’s Couloir. Barry and Dave would tackle the Ridge itself, nearer, but less appetizing. We headed out, following the corniced edge. Finally, where the cornice faded, we stepped across into Tibet. As we climbed, the cauldron overflowed and once again the mountain was lost in cloud. At 24,500 feet we nibbled a bit of frozen tuna and fruitcake, waiting in vain for some hint of our objective. Toward three we turned back, picking up Dave and Barrel on the way.

It was hardly a cheerful evening. The two days of reconnaissance originally planned were gone. Our hope had been to surmount the first step, but thus far we hadn’t even reached the base of the Ridge. This side of the mountain could be climbed by a well-equipped, full-scale attempt; chances for a small offshoot of the major effort seemed pretty slim. For Sherpas to carry loads over that rock would require days of route preparation with fixed ropes and ladders. It seemed hopeless.

Dave was for going down in the morning. “We shouldn’t burn ourselves out here for nothing,” he said. “They can use us on the Col.” The logic was sound, except that there were too many people on the Col already. Willi, Barrel, and I felt a gnawing doubt. How much might the weather and our poor acclimatization be influencing our judgment? We hadn’t even set foot on the rock yet, and views through binoculars can be notoriously deceptive, particularly head on. There couldn’t be much up there to change our minds, but we owed it to ourselves to take one more look. Enough oxygen remained for that. If we were to write it off, at least we’d like to go as high as we could, just for the hell of it. So we left it up to the weather. In my diary I willed myself a little higher. “Tomorrow, if possible, I will get to the Couloir.”

The 12th started clear. I had the ice melting at six, and by eight, as the interior rain began to fall, we were through breakfasting on meat loaf from the evening before. Still, it was ten before we were under way. Half an hour later, even on a full flow of oxygen, Dave decided he couldn’t make it. He had fared poorly, plagued with the same symptoms of incomplete acclimatization he’d had at Camp 1. This led to a lack of enthusiasm for the route, which made him possibly the only realist among us. We watched him safely back over the bergschrund to the tent, then re-roped, with Barrel in the middle, and continued on to the Shoulder. Everest stood clear, rid even of its wind-blown banner. Ten thousand feet below, the Rongbuk Glacier wound northward into brown Tibetan hills. Ice towers on the glacier appeared as hundreds of tiny, ice blue gems. Through binoculars we sighted the remains of the Rongbuk Monastery in the rubble left by the receding ice. It had been destroyed by the Chinese a few years before.

Yesterday’s high point came easily by 1 PM, then we were on new terrain. Clouds coalesced, a light snow fell, crampons scraped across out-sloping rock and scratched superficially on glare ice. As I strolled along in the rear for the time, I mused on the inadequacies of an ice-ax arrest on such an ice-rink surface. Just don’t fall, that’s all, I thought. Climbing on his front crampon points, Willi led up a tiny fissure diagonally transecting a bulge of glare ice. At the top he rammed his ax into the crack to belay Barrel. Waiting below, I discovered Barrel was tied in closer to me than to Willi. He would be unable to reach Willi’s stance unless I moved along with him. His expression of astonishment as he turned to belay me and found me standing behind him was worth the lack of protection it cost in climbing up there.

With time for thoughts as we strolled along, I began to play games with my oxygen. Willi was leading on two liters. At that flow I could hold the pace with a reserve that allowed for reverie; on one liter it was an effort, and with the oxygen turned off I could barely keep up, my heart and lungs pounding to their limit. In another game, I would squeeze the entire contents of the rubber oxygen bladder into my lungs with a single, deep breath. In effect, this suddenly returned me to sea level. Within three or four seconds the bolus of well-oxygenated blood reached receptors, which sent their message to my brain. Momentarily my breathing almost ceased, and the fleeting respite from panting was pure pleasure. As the oxygen-rich blood reached my fingertips, they changed from purple to bright pink—and to purple again as I was suddenly returned to high altitude.

Perhaps there was too much time for thought. Somewhere during the course of our journey my objectivity succumbed to emotion. I decided the West Ridge was worth a try; I only hoped Willi would agree. Otherwise, we’d go clear to the base of the Couloir, if necessary, to convince him. Although this would mean wandering back to camp in the dark, the prospect seemed less forbidding at the moment than it should have.

At four we reached the rock, 25,100 feet, according to the altimeter. The Diagonal Ditch rose immediately above, to dissolve in fog and swirling snow. What we could see didn’t look unreasonable, but we couldn’t see much. We sat on the down-sloping slabs, munching rum fudge.

“All right, Willi. Have you made up your mind? Or do we have to go higher still?”

“I’m convinced, Tom. This is far enough for today.”

So the decision was made in the pit of our stomachs. Perhaps the day’s walk had provided only the solitude for a necessary bit of introspection.

All doubts that might have lingered were removed moments later when we traversed the hundred yards to the ridge crest, where the West Shoulder butts against the mountain itself. Here, at the very inception of the West Ridge, was a flat platform of wind-rippled snow, roomy enough to house all the tents we would require. The far edge was bounded by a rock promontory from which we peered past our feet at the tiny cluster of tents nestled in the Western Cwm. The summit of Nuptse was directly across the way, now scarcely above us. Lhotse filled the end of the Cwm, for the first time unforeshortened. In the foreground Everest’s South Face rose 4,000 feet and fell an equal distance to the Cwm. The summit of the mountain was hidden. To the north, the slope rounded from view—dropping to the Rongbuk Glacier. The scene was clothed in a seductive beauty of boiling clouds, glazed golden by the brilliance of the evening sun, cloud shadows alternating with shafts of sunlight which bathed the ridges and reflected intensified from millions of tiny ice crystals floating in the cooling air. Was this the mountain’s design to capture us? All doubt about our decision vanished with the spectacular dissolution of the storm. We headed down.

Dave was perplexed by our decision. He had been busy discarding food during our absence, convinced our departure the next day would be permanent.

“How did the route look?” he asked.

“Well, we really couldn’t see much. Mighty cruddy rock though. But you should see the beautiful place for 4W. It’s worth a try just to be able to live there a while.”

And so the decision was made. We’d be back up. My diary reflected my weary bliss: “Tomorrow, if possible, I will go restfully to 2.”

The West Shoulder from Camp 3 on the Lhotse Face (Photo by Norman G. Dyhrenfurth)

Nuptse (across) and Western Cwm (below) from Camp 4W’s promontory (Photo by Willi Unsoeld)

An oxygen-masked Tom Hornbein on the West Shoulder (Photo by Willi Unsoeld)

Willi Unsoeld and photographer Barry Bishop at promontory and future site of Camp 4W with Nuptse in the background (Photo by Tom Hornbein)

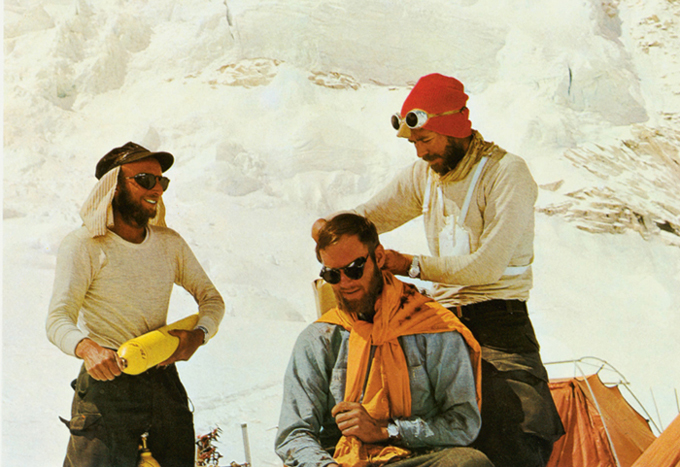

In Camp 2: Tom Hornbein, Barry Corbet, and Dick Emerson (Photo by Al Auten)