|

Play for more than you can afford to lose, and you will learn the game. |

—WINSTON CHURCHILL

We were stacked irresolutely about the tent: Barry, Al, Willi, Ang Dorje, Dick, and I. Dick appeared none the worse for his night out. It was hard to regret that we were beaten, so enticing was the prospect of fresh meat and unlimited eggs awaiting us at Base Camp, and the prospect of our homeward journey. To be off this mountain once and for all was the only goal with any meaning. We would have continued down to Advance Base that same day, but we were too tired. We crawled into our bags that night with the feeling that it was all over. The prospect of escaping from this inhospitable lump that could out of sheer whimsy blot us neatly from the scheme of things was pure delight. The lure of home was stronger still, the welling-up of love and longing. And strongest of all was the prospect of finally being freed from the lure of the mountain. The invisible line that linked me to Everest was frayed.

But it hadn’t broken. I wasn’t yet free to make my own decision. We hadn’t given it all we had. Descend now, and we must live the rest of our lives with that knowledge. So the bond still held fast. But it would be sheer fanaticism to suggest going back up. Weary muscles voted against the taunting of my mind; still I couldn’t shake it off. Our tents were ruined, a lot of food blown away. And oxygen? Four Sherpas had beat a hasty retreat to Advance Base. Three days ago we had fifteen, now only three remained, Ang Dorje, Passang Tendi, and Tenzing Nindra. We could salvage two four-man tents from here. Maybe we could get a small one from Advance Base. And a couple more Sherpas. But time was running out. We were scheduled to leave Base in a week.

Months before, in our early planning we had toyed with the idea of having only five camps, instead of six as on the Col. It would cut down the number of carries high on the mountain over terrain few of our Sherpas would be skilled enough to climb. The idea was ridiculous. How could we hope to travel farther in a day over steep, difficult terrain than on the easier ground of the regular route? We discarded the idea as naïve folly. We’d need at least six camps. Two two-man summit teams on successive days went without saying.

We had been hamstrung by the wind, and new questions kept me awake: Can we possibly consider going up? Suppose we eliminate a camp and try for a very long carry above 4W? A long shot, but it’s the only chance we have. Over 2,000 vertical feet in a day? Maybe, if the climbing isn’t too tough and the loads are light. If we can get two more Sherpas, that’ll still be 40 pounds apiece—for just one summit team. There isn’t time for a second one anyway. No time to send our recon a day early to locate the high camp. They’ll just have to get up early and hope the going is not too hard.

So we have a chance. If the Sherpas will agree to one more carry. It’s worth a try. I was bursting to tell my plan to Willi. With the dawn I could contain myself no longer. I kneed him in the ribs.

“Excuse me. I didn’t mean to wake you up. But since you are, what do you think of this?”

Willi forced open a sleepy eye and listened, wondering whether what he heard was sheer genius or only my pathological fanaticism. Undoubtedly the latter, he must have thought, but still it was a chance.

“O.K. Let’s try it on Barry.”

Barry bit. We crossed to the other tent and accosted Dick and Al. And so it was agreed. We called Base on the radio and Willi presented our plan.

Dyhrenfurth (Base): Willi, I’m delighted by your plan. This is exactly what we were going to suggest, that only two men make the attempt. And all I can say is, Willi, you’ve had a hell of a lot of tough luck. You’ve worked awfully hard. And we’re all 200 percent with you. We wish you all the luck in the world and hope you make it. Over.

Unsoeld (3W): Thanks a lot, Norm. We appreciate that and I’m especially appreciative that we’re thinking along the same lines. Really, this is probably a terrifically long shot. If we can carry through to 27,000 or so and then have to retreat we would all feel as if we had completed an adequate reconnaissance of the route. With 90 percent of the labor already done, getting the things up to 4W, it seems too bad to come down without one last all-out push, which, with a little bit of luck, we’ll carry out. Thanks a lot, Norm. Over.

Dyhrenfurth (Base): Willi, we all thank God, or course, that you are all alive, that nobody got hurt, and whether you make it or not, in any case you have accomplished miracles. I think the mountaineering world, I’m sure, will recognize that this is an incredible accomplishment on a long and difficult and unknown route. Over.

Willi (3W): Thanks a lot. We share your joy in all being alive, all right. There were a few times when things were flying around wildly that we weren’t sure but that some of the objects were us. And, I don’t know, if we just get one break in the weather now, it’s entirely possible to go all the way. The Couloir really looks good. The section of it that Tom and I were in looked like it was the steepest of all that we could see and it was a maximum of thirty to thirty-five degrees. So it didn’t look like a difficult route as far as we could see. The upper part of the mountain might give us something we can really sink our teeth in. Over.

Dyhrenfurth (Base): Willi, it sounds very, very good. All the luck in the world. As they say in German, Hals und Beinbruch. Over.

Al took to the air to consult Prather about replacing gear lost in the storm.

Auten (3W): We’ll need a couple of packs. Mine and Barry’s took off and are somewhere in China by now. Also two pairs of goggles, and two of down mitts. Hornbein says he needs some Bouton goggles, too, and a balaclava. And Jimmy’s two-man Gerry tent at Advance Base if he can give it up.

Prather (Base): Mighty fine. Big Jim sends good word up to you. He’s sending his pack up to you, and he says that the pack’s been to the summit. It’s a very expensive pack. And he says if you lose his pack your soul had better go to Heaven because your ass will be his. Over.

We were completely on our own. For all the well-wishing we knew the impatience of those below to be homeward bound. They knew our chances were dim; it was kindness that they still waited. I guess they also knew we wouldn’t come down until we were damned well through. We had kept the ridge attempt alive against an opposition which we thought was founded on doubt and lack of interest. Though hardly burdened with manpower or supplies, we were finally in position.

We rested the next two days, and waited for supplies. On the first morning Al wanted to go down. He had worked hard and well, but only a little of our enthusiasm for the route had rubbed off on him. Now he could see Dick assuming his original role in the foursome, with himself as excess baggage. I protested.

“We need all the manpower we can get,” I said. “Dick’s strength is still a big question and anyone of the rest of us could wake up sick tomorrow. Let’s not cut it any thinner than it is already. We need you.”

Al stayed.

The 18th and 19th were perfectly clear. Our colorful down clothes bloomed atop the tents. The summit of Everest stood a mile above, windless and inviting. The afternoon of the 19th, Ila Tsering and Tenzing Gyaltso arrived, all smiles, with our fresh supplies. Our discussion that afternoon went once more over the final plans. Till now we had not decided on the final route. Hornbein’s Couloir lay far out on the Tibetan North Face, almost in a fall line below the summit; Jake’s was a large snowfield leading back up toward the West Ridge. We were drawn toward the latter, because it would return us to the Ridge we had meant to climb. But we no longer had the strength to move a camp up that kind of terrain. We had to get it above 27,000 feet in the easiest way possible. With time for but one long carry, Hornbein’s Couloir appeared to offer us the only chance. Where the Couloir went, above the camp, we couldn’t guess. We’d just have to take our chances on the final day.

Dick broached the last unaired issue. “I’d think in all fairness we ought to discuss the choice of the summit team. I don’t mind being outspoken since I’m not in shape for it anyway. There’s no question that Barry, Tom, and Willi are in the best shape. I think this is the first consideration.”

We weighed the various pairings.

“I think Willi and Tom should go,” Barry said. “For one thing you’ve plugged harder on the route than any of the rest of us.”

“All the more reason for you to have a turn, Barry,” Willi replied.

In the six weeks we’d been on the mountain, Barry had not tasted a day of real climbing, of pushing a route over new terrain. He’d spent his time humping loads and toiling over the winch, or sitting restlessly at Advance Base. Though he said little, his frustration and disappointment were apparent. He had discovered that there wasn’t much real climbing involved in climbing the highest peaks on earth. He was a superb mountaineer. He could have easily gone to the top.

“Another thing,” Corbet continued, “you two have been climbing together; you know each other, and you’ll make the strongest team. What’s more, you’re both just about over the hump. This is my first expedition. I’ll be coming back again someday.”

So tentatively Willi and I were to be the summit team. The final decision would be made at our high camp two days later. If either of us fell out, Barry would plug the hole. We tackled the final problem in our tent that night. Barry would reconnoiter to find high camp. We had to decide who would accompany him. They’d have to start early and move fast to find and prepare a route for those following a few hours later. Dick had still not fully recovered from his illness. We doubted he could hold the pace. All things considered, it was decided that Al would go with Barry.

May 20 was the third perfect day in a row. How long could the weather hold? We struck the two tents that were to go to 4W. The snow had drifted level with their flat tops on the uphill side. Then the warmth from inside had caused a layer of ice to form. They were solidly imbedded. Much chopping finally extracted the tents with only a few additional holes for better ventilation. Willi and I sorted personal gear, some to stay at 4W, some to go up. A few pages were torn from the back of our diaries so that Emerson’s study could continue uninterrupted without our having to carry the entire books over the summit. Shortly after noon we saddled up, set our oxygen at two liters per minute, and headed for the West Shoulder. The two day’s rest had worked wonders.

Thinking of the possible traverse of Everest I said, “You know, Willi, if we’re really lucky this may be the last time we see 3W.” We both must have shared the next thought: Yes; and also if we’re unlucky.

As we approached the Shoulder we could see the prayer flag Ang Dorje had planted there, flapping in the wind. Like a couple of proud children about to reveal their most treasured hideaway, we watched Dick come over the top for his first view of the other side. His silence as he looked was all we needed to make the moment perfect. We pointed out the landmarks of our route, so far as it went.

As Dick began to photograph the route, Willi remembered leaving his haze filter in my rucksack at 3W. Deciding that such picture-taking opportunities might not come his way again, he left his pack and headed back down. The others moved on up toward 4W to begin the salvage job while I waited on the crest of the ridge for Willi.

For almost the first time during the entire expedition I was completely alone. I sat atop the ridge with my mittens off, soaking up the windless warmth of the afternoon sun. I looked across brown hills, deep glacial valleys, snow peaks ranging westward into haze. My thoughts knew only the restriction imposed by the limits of my ability to feel and comprehend. A vertical mile above, at the far end of the West Ridge, was the highest point on earth. The day after tomorrow? The dream of childhood, not to be lost? My gaze climbed lightly up each detail of our route, to the base of the Couloir at 26,000 feet. The rest was unknown, partly hidden, grossly foreshortened, but all there.

Like pain, a mountain can be a subjective sensation; for all its solidity and fixity of form, it is more than what one sees. It is awe, pleasure, respect, love, fear, and much, much more. It is an ever-changing, maturing feeling. Over the weeks since we had first stood on the Shoulder to see the black rock of the last 4,000 feet, my feelings toward the climb had steadily ripened. That rock couldn’t be divorced from the summit to which it led. Yet each time we looked, the slope seemed a few degrees gentler, the vertical distance not quite so unreasonable. After all, we had climbed steeper faces and longer distances, and on more rotten rock. But all together? And above 27,000 feet instead of half that high? However, you can’t see altitude. Might as well ignore it. We chose not to dwell on problems like what happens if you run out of oxygen below the summit. And what it’s like to climb on rotten rock at 27,000 feet, ballasted by a 40-pound pack.

Everest came down off Everest. It became, in a climbing sense, just another mountain to be approached and attempted within the context of our past experience in the Rockies, Tetons, or on Mount Rainier. Not quite, really. But much of the battle lay inside. That battle was nearly won. I looked out beyond the Great Couloir to the step where Mallory and Irvine were last seen. So near the Everest of my boyhood, I felt uneasy, as if I were trespassing on hallowed ground. I looked on the same North Face at which they had looked forty years before; I felt what they must have felt. The past was part of the rightness of our route.

Beyond the remains of the Rongbuk Monastery were the barren hills of Tibet, a strange land of strange people, living beneath the highest mountain on earth—did they know it? What difference did it make to them? I thought of home. It would be night there, everyone asleep. Can Gene feel my thoughts coming home? I took my photo album from my shirt pocket, and looked at the portraits inside. Tears came. Sheer, happy loneliness, the feeling of being nearly finished with the task I had set myself. It wouldn’t be long now.

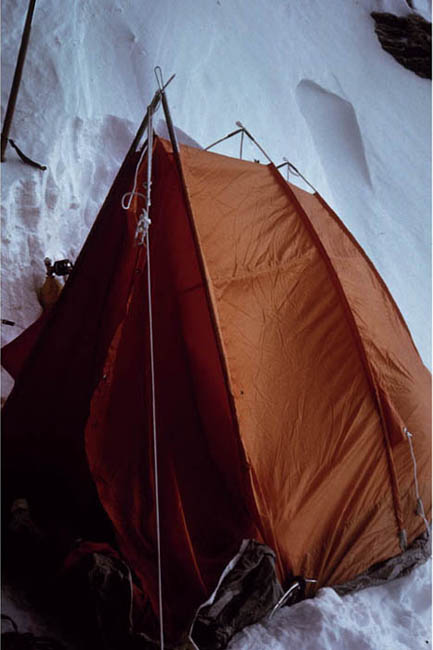

Completely alone. Range on range hazed westward. Beneath me clouds drifted over the Lho La, chasing their shadows across the flat of the Rongbuk Glacier. I remembered afternoons of my childhood when I watched the changing shapes of clouds against a deep blue sky, seeing elephants and horses and soft mountains. On this lonely ridge I was part of all I saw, a single, feeble heartbeat in the span of time and space about me. Willi was back. He came steaming up the hill on full flow from a cylinder strapped to his back, his haze filter clutched in one hand. He checked his watch to confirm what undoubtedly must stand as a world’s record for the run from 3W to the West Shoulder. Once he had caught his breath we took one last look at the sweep of mountain above us; henceforth we would be too much a part of it, able to locate ourselves only in the memory of this last soaring view. Squandering oxygen, we pressed the pace to join the others in rehabilitating the wreckage of 4W. Most of the oxygen bottles were still there, and enough butane if we used it carefully. But of twelve food boxes only three remained. One, fortunately, contained our high-camp ration. As Barry busily filmed us we began to pitch the tents. Four days before we had been forcibly made aware of the reason for our flat campsite, but there was no place else to put it. We oriented the two four-man tents with their broadsides less exposed to any recurrence of storm.

The walls flapped disconcertingly in the westerly breeze. Al carefully enmeshed the cluster with climbing ropes. The remnant of our original two-man tent was suspended from the frame of one of the larger tents; its own poles had been bent beyond repair. This sagging structure was to be Barry’s and Dick’s. Al would share one of the big tents with Ang Dorje and Tenzing Gyaltso. Feeling isolated, Al objected. Reluctantly the Sherpas consented to inhabit the ruined tent. They straightaway crawled inside and refused to come out for supper.

“Not hungry, Sahib,” said Ang Dorje, “only need sleep. O.K. tomorrow.”

But we wondered how much they were offended. Knowing the highs and lows of their temperament, we worried that they might remain in bed “sick” in the morning. I crawled into their tent to rig their sleeping oxygen and try to persuade them to have some tea. Later Willi went over through the cold of the night to chat with Ang Dorje.

Our plans for May 21 seemed a little ridiculous. First, Barry and Al had to explore and prepare an unknown route to the site for our high camp, 5W. We would give them a 2½-hour head start. Next, five untried Sherpas must traverse the North Face, climbing more than 2,000 vertical feet with loads, twice the distance ever carried before at that altitude.

In the bitter, pre-sun cold, Al and Barry departed. They carried fixed rope, pitons, ice screws, and one oxygen cylinder each. They also carried all our hopes for the following day. After breakfast Dick, Willi, and I prepared the loads for the Sherpas. I checked the pressure in all the oxygen cylinders, setting aside the six fullest for the final push. By nine the sun was warming the tents, but there was still no sign of Ang Dorje and Tenzing Gyaltso. We began to consider seriously the consequences should they not show, when a smiling face appeared at their tent door.

“Good morning, Sahibs. Ready go,” Ang Dorje said. Ila Tsering looked over at Ang Dorje, supposedly past his prime but somehow totally infected with the pleasure of our gamble, then at the three other young Sherpas, all on their first expedition.

“All good Sherpas Base Camp, Sahib. Only bad Sherpas up here,” he said. Delighted laughter, theirs and ours, got us on our way. Each shouldered a load of about forty pounds, counting the oxygen he would use during the day. Ila hefted his load.

“Very heavy, Sahib,” he said. We took turns lifting it. Sure enough, our food ration weighed about ten pounds more than the other loads. He grinned. “But this last day,” he said, “I carry.”

At 9:30 the five Sherpas were roped together. I checked their masks as they filed past and set their regulators at a flow of 1½ liters per minute. They followed Barry and Al’s tracks toward the Diagonal Ditch. Twenty minutes later Willi, Dick, and I pulled out. Willi and I carried only a single bottle of oxygen, cameras, radio, flashlight, and our personal belongings.

The Sherpas stayed one jump ahead. The three of us were completely absorbed in the pleasure of climbing together for the first time since Masherbrum. Since our visit five days before, the slope had changed radically. Entire snowfields had been blasted into oblivion, leaving us to scrape our crampons across an abundance of downsloping, fractured rubble. Far ahead we could see the figures of Barry and Al silhouetted against the snow as they disappeared into Hornbein’s Couloir.

Camp 4W and the Rongbuk Glacier (Photo by Willi Unsoeld)

For me the pleasure of the walk was tempered by anxiety. Could Al and Barry get to 27,500?

It was early afternoon before we reached the base of the Couloir, at 26,250 feet. Showers of ice cascading from above drew our attention to the tiny figures etched against the snow 800 feet higher. Barry was chopping away for all he was worth, hewing a staircase for us. We joined the Sherpas under a partly protected wall to await the end of the onslaught and nibble a bit of lunch. The Sherpas seemed less enthusiastic as they huddled to avoid the constant bombardment of ice spewing out the end of the gully and whirring past our heads with a high-pitched whine. We dallied over our sardines, pineapple, and chocolate, all frozen tasteless. The prospect of entering the gully was too much like becoming tenpins in a high-angle bowling alley.

A little after 2:00 PM the ice fall abated. With Ang Dorje paternally in the lead, the Sherpas started up, their flow increased to 3 liters per minute. Dick had reached this select 8,000-meter level with little difficulty. He would have liked to go higher, but it seemed more sensible for him to remain here, conserving his energy and oxygen to assist the others on their late return to 4W. Our masks could not hide tears when it came time to head on up.

“Must be the altitude,” said Willi.

“Don’t do anything foolish, you nuts,” Dick said. Then, as an afterthought, with a twinkle in his eye, “See you back at 2.”

For a long time as we climbed we could look down on the back of Dick’s head as he sat on that lonely ledge, looking out into Tibet.

The shadows were lengthening across the glaciers 12,000 feet below. It was nearly 4:00 PM when we looked up to see Al and Barry, their two heads peering gnome-like from a snow ledge at the base of the Yellow Band. We shouted encouragement to the Sherpas, now below us, for they were beginning to suspect their Sahibs of wanting to pitch the last camp on the summit itself. The slope of the staircase Barry had carved steepened to about forty degrees as we came up to them. He filmed our arrival.

“O.K. Willi, come up around the end and turn toward me, and smile.”

Willi smiled beneath his oxygen mask. My first breathless question as I reached the ledge was, “How high are we, Barry?”

“The altimeter says 27,200 and it’s still rising.”

“Wow! Tremendous. You guys did it!”

We’d have a long day tomorrow—but it was possible. Willi had been hastily surveying their choice of a campsite. It was a wind-scooped depression running beneath the cliff for about 10 feet. At the wide end it might have been 12 inches across.

“Where’d you find such spacious accommodations?” he asked.

“We knew you’d be satisfied with nothing but the best,” Barry said, “but it’s the only possibility we’ve seen all afternoon. Anyway you’ll be able to keep warm digging a platform when we leave. Only please don’t knock any ice down on us.”

With the Sherpas clinging to the slope by their axes, we hacked out a hasty ledge, then gingerly passed the tent, food, and oxygen bottles up to it.

“Careful. If we lose a bottle of oxygen we’re through.”

It would be dark before they reached 4W. Again tears came as we thanked Ang Dorje, Ila, the two Tenzings, and Passang Tendi. “Good luck, Sahib,” each one said as we clasped hands. Then we said goodbye to Barry. And to Al. Barry sank his ax into the snow to anchor the rope. Al led off, followed by the Sherpas. They slid quickly down the fixed line. Then Barry pulled his ax, descended carefully to them and repeated the process.

“Just like guiding Mount Owen, Willi,” he shouted up.

There was only a brief moment to feel the grandeur of our impending isolation. We had to contrive some architectural plan for carving a tent platform from an excessively steep slope of snow.

“How about parallel to the cliff?” I asked.

“I think it’ll take less digging if we diagonal it out into the gully.”

For the next hour and a half we chopped, jumping on the pieces to pulverize them to a size less painful should they accidently be launched on to the party descending below. Every effort was breathtakingly slow.

“Think it’s big enough?” Willi asked.

“Let’s give it a try.”

With the wind threatening to blow it away, we pitched the tent.

“Nope. Not quite big enough. It seems to hang over a bit on the outside,” I said. The platform was a good foot too narrow.

“How much do you weigh, Tom, boy?”

“About 130, stripped. Why?”

“I have you by 25 pounds. Maybe you better sleep on the outside.”

I climbed in to start supper while Willi secured the tent to the slope. One rock piton driven half an inch into the rotten rock of the Yellow Band anchored the uphill ties, our axes buried to the hilt in equally rotten snow pinned the outside corners.

Willi ceremoniously planted the prayer flag Ang Dorje had left. “I think we’d better count on this,” he said. It promised to be a classical high-camp night on Everest: wind batters the tent while its occupants cling to the poles inside, sipping a cold cup of meager tea. We had the wind, the insecure platform—and the enticing prospect of a two mile vertical ride into Tibet if our tent let go. But these modern tents had the poles on the outside; there was nothing to cling to. We turned to our meager fare. This began with chicken-rice soup, followed by a main course of butter-fried, freeze-dried shrimp in a curried tomato sauce, crackers and blackberry jam, and a can of grapefruit segments for dessert. All this was interspersed with many cups of steaming bouillon. Our greatest sorrow was that we could do away with only two-thirds of the four-man luxury ration. We turned to a bit of oxygen as a chaser; once again we had overeaten.

Everything was readied for an early start. For this one night I succumbed to Unsoeld’s slovenly habit of sleeping fully clothed, except for boots, which were the foundation under the outer half of my air mattress. While Willi stacked the oxygen bottles in the vestibule, I melted snow for tomorrow’s water. This and the butane stoves would share the warmth of our sleeping bags to prevent their freezing during the night.

About nine Willi awoke from his after-dinner nap, gripped by an overwhelming urge to relieve himself which had for some time been overwhelming me. I promptly encouraged his leaving the tent by offering him a belay. “No thanks, Tom. A guide can handle these things himself.”

He disappeared into the gusty blackness, his flashlight inscribing chaotic circles of light. What a horrible way to go, I thought. And he has the flashlight! After a time he returned, triumphant. We finished the evening religiously filling out Emerson’s diary. Once more violating the classical Everest tradition, we turned our sleeping oxygen to one liter each and settled into the humidity of our plastic sleeping masks. To the lullaby of the wind shaking our high and lonely dwelling, we fell into a deep sleep. But just before that I wrote a letter home, without oxygen:

May 21

Camp 5W, 27,200

Genie:

Just a brief note on our hopeful summit eve. 9.00 p.m. Willi and I perched in a hacked-out platform at the base of the Yellow Band in Hornbein’s Couloir. The morrow greets us with 2,000 feet to the top, the first of which looks like some good rock-climbing. Very breathless without oxygen. Mainly, as wind rattles the tent and I hang slightly over the edge, would have you know I love you. Tomorrow shall spell the conclusion to our effort, one way or another.

Good night.

Love always,

TOM

Sherpas departing 4W (Photo by Willi Unsoeld)

Sherpas ascending the Diagonal Ditch (Photo by Willi Unsoeld)

Tom Hornbein and Martian friend (Photo by Richard M. Emerson)

Dick Emerson and Tom Hornbein ascending the Diagonal Ditch (Photo by Willi Unsoeld)

The tent at Camp 5W (Photo by Willi Unsoeld)