—JAMES R. ULLMAN

—JAMES R. ULLMAN

The rest is like a photograph with little depth of field, the focused moments crystal sharp against a blurred background of fatigue. We descended the gully I had been unable to find in the dark. Round the corner, Dave and Girmi were coming toward us. They thought they heard shouts in the night and had started up, but their own calls were followed only by silence. Now, as they came in search of the bodies of Lute and Barry they saw people coming down—not just two, but four. Dave puzzled a moment before he understood.

The tents at Camp 6—and we were home from the mountain. Nima Dorje brought tea. We shed boots. I stared blankly at the marble-white soles of Willi’s feet. They were cold and hard as ice. We filled in Emerson’s diary for the last time, then started down. With wind tearing snow from its rocky plain, the South Col was as desolate and uninviting as it had always been described. We sought shelter in the tents at Camp 5 for lunch, then emerged into the gale. Across the Geneva Spur, out of the wind, on to the open sweep of the Lhotse Face we plodded in somber procession. Dave led gently, patiently; the four behind rocked along, feet apart to keep from falling. Only for Willi and me was this side of the mountain new. Like tourists we looked around, forgetting fatigue for the moment.

At Camp 4 we stopped to melt water, then continued with the setting sun, walking through dusk into darkness as Dave guided us among crevasses, down the Cwm. It was a mystery to me how he found the way. I walked along at the back, following the flashlight. Sometimes Willi stopped and I would nearly bump into him. We waited while Dave searched, then moved on. No one complained. At 10:30 PM we arrived at Advance Base. Dick, Barry, and Al were down from the Ridge, waiting. Frozen feet and Barrel’s hands were thawed in warm water. Finally to bed, after almost two days. Short of a sleeping bag. Willi and I shared one as best we could. May 24 we were late starting, tired. Lute, Willi, and Barrel walked on thawed feet. It was too dangerous to carry them down through the Icefall. Willi, ahead of me on the rope, heeled down like an awkward clown. The codeine wasn’t enough to prevent cries of pain when he stubbed his toes against the snow. I cried as I walked behind, unharmed. At Camp 1 Maynard nursed us like a mother hen, serving us water laboriously melted from ice samples drilled from the glacier for analysis. Then down through the Icefall, past Jake’s grave—and a feeling of finality. It’s all done. The dream’s finished.

Descending from Camp 6 to Camp 5 on the South Col (Photo by Barry Bishop / ©1963 National Geographic Society)

No rest. The next day, a grim grey one, we departed Base. From low-hanging clouds wet snow fell. Willi, Barrel, and Lute were loaded aboard porters to be carried down over the rocky moraine. It was easier walking. At Gorak Shep we paused. On a huge boulder a Sherpa craftsman had patiently carved:

Clouds concealed the mountain that was Jake’s grave. As we descended, the falling snow gave way to a fine drizzle. There was nothing to see; just one foot, then another. But slowly a change came, something that no matter how many times experienced, is always new, like life. It was life. From ice and snow and rock, we descended to a world of living things, of green—grass and trees and bushes. There was no taking it for granted. Spring had come, and even the grey drizzle imparted a wet sheen to all that grew. At Pheriche flowers bloomed in the meadows. Lying in bed, Willi and I listened to a sound that wasn’t identifiable, so foreign was it to the place—the chopping whirr as a helicopter circled, searching for a place to land. In a flurry of activity Willi and Barrel were loaded aboard. The helicopter rose from the hilltop above the village and dipped into the distance. The chop-chop-chop of the blades faded, until finally the craft itself was lost in the massive backdrop. The departure was too unreal, too much a part of another world, to be really comprehended. Less than five days after they had stood on the summit of Everest, Barrel and Willi were back in Kathmandu. For them the Expedition was ended. Now all that remained was weeks in bed, sitting, rocking in pain, waiting for toes to mummify to the time for amputation.

Up over barren passes made forbidding by mist and a chill wind, we travelled. Hard work. Then down through forests of rain-drenched rhododendrons, blossoming pastels of pink and lavender. Toes hurt. Two weeks to Kathmandu. Feet slipped on the muddy path. Everything was wet. We were finished. Everest was climbed; nothing to push for now. Existence knew only the instant, counting steps, falling asleep each time we stopped to rest beside the trail. Lester, Emerson, and I talked about motivation; for me it was all gone. It was a time of relaxation, a time when senses were tuned to perceive, but nothing was left to give.

Pleasure lay half-hidden beneath discomfort, fatigue, loneliness. Willi was gone. The gap where he had been was filled with a question: Why hadn’t I known that his feet were numb? Surely I could have done something, if only…I was too weary to know the question couldn’t be resolved. Half of me seemed to have gone with him; the other half was isolated from my companions by an experience I couldn’t share and by the feeling that something was ending that had come to mean too much. Talk of home, of the first evening in the Yak and Yeti Bar, of the reception that waited, was it really so important? Did it warrant the rush?

We’d climbed Everest. What good was it to Jake? To Willi, to Barrel? To Norman, with Everest all done now? And to the rest of us? What waits? What price less tangible than toes? There must be something more to it than toiling over the top of another, albeit expensive, mountain. Perhaps there was something of the nobility-that-is-man in it somewhere, but it was hard to be sure.

Yes, it satisfied in a way. Not just climbing the mountain, but the entire effort—the creating something, the few of us molding it from the beginning. With a lot of luck we’d succeeded. But what had we proved?

Existence on a mountain is simple. Seldom in life does it come any simpler: survival, plus the striving toward a summit. The goal is solidly, three-dimensionally there—you can see it, touch it, stand upon it—the way to reach it well defined, the energy of all directed toward its achievement. It is this simplicity that strips the veneer off civilization and makes that which is meaningful easier to come by—the pleasure of deep companionship, moments of uninhibited humor, the tasting of hardship, sorrow, beauty, joy. But it is this very simplicity that may prevent finding answers to the questions I had asked as we approached the mountain.

Then I had been unsure that I could survive and function in a world so foreign to my normal existence. Now I felt at home here, no longer overly afraid. Each step toward Kathmandu carried me back toward the known, yet toward many things terribly unknown, toward goals unclear, to be reached by paths undefined.

Beneath fatigue lurked the suspicion that the answers I sought were not to be found on a mountain. What possible difference could climbing Everest make? Certainly the mountain hadn’t been changed. Even now wind and falling snow would have obliterated most signs of our having been there. Was I any greater for having stood on the highest place on earth? Within the wasted figure that stumbled weary and fearful back toward home there was no question about the answer to that one.

It had been a wonderful dream, but now all that lingered was the memory. The dream was ended. Everest must join the realities of my existence, commonplace and otherwise. The goal, unattainable, had been attained. Or had it? The questions, many of them, remained. And the answers? It is strange how when a dream is fulfilled there is little left but doubt.

|

Never let success hide its emptiness from you, achievement its nothingness, toil its desolation. And so keep alive the incentive to push on further, that pain in the soul which drives us beyond ourselves. Whither? That I don’t know. That I don’t ask to know. |

—DAG HAMMARSKJÖLD

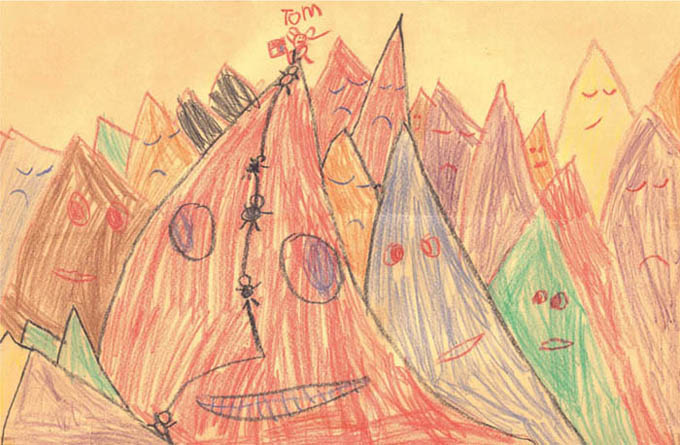

“Tom” and his children on Everest, as drawn by four-year-old Betsy Hornbein, May 1963

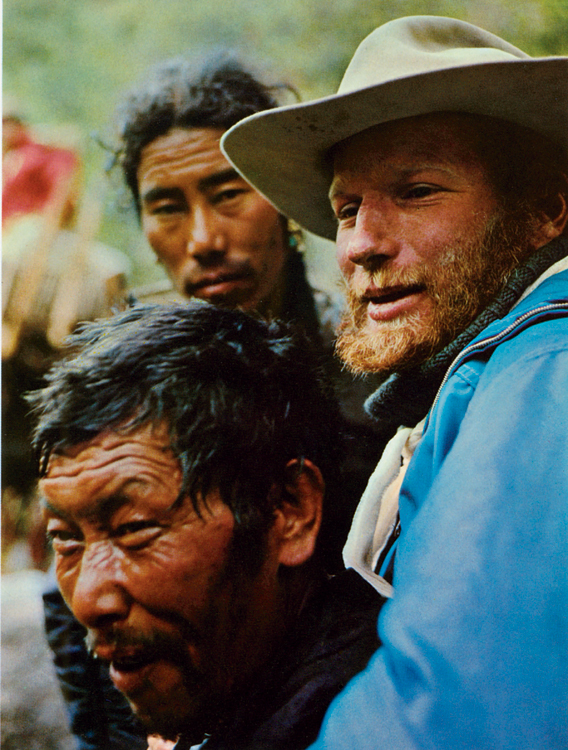

Willi Unsoeld being carried by porter (Photo by James Lester)

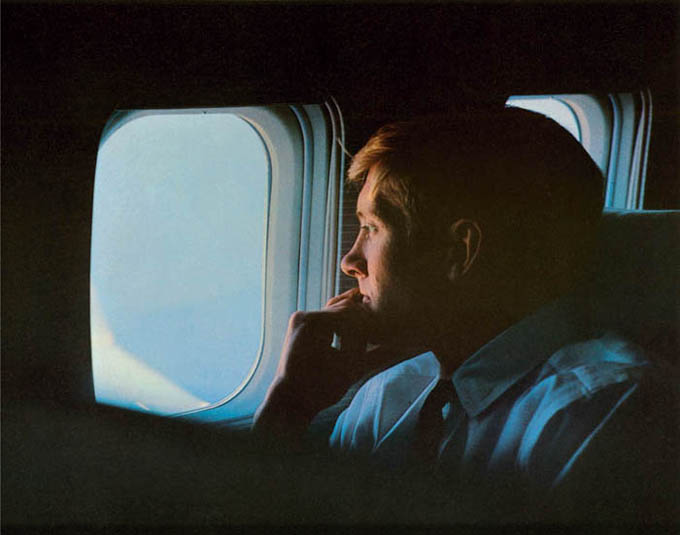

Frostbitten Willi Unsoeld getting a lift to the helicopter (Photo by James Lester)

Willi Unsoeld and Tom Hornbein approaching the West Ridge (Photo by Barry Bishop)

Jake Breitenbach (Photo by James Lester)

John Edgar Breitenbach was killed on March 23, 1963, in the Khumbu Icefall of Mount Everest by a collapsing wall of ice.

Jake climbed throughout North America, made significant ascents in the Tetons, climbed McKinley by the West Buttress and again by the western rim of the South Face, and attempted Mount Steele in the St. Elias Range. He was a member of the 1963 American Mount Everest Expedition. Jake was a fine mountaineer. He never climbed Mount Owen, although he went to within a yard of the summit many times. He thought that someday he might want to climb Owen for the first time, and perhaps he enjoyed the courting.

He graduated in mathematics from Oregon State College, then made his home in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where he guided for six years and operated a ski shop. He is survived by his wife, his parents, a brother, and his friends, all of whom loved him.

Exultant, tolerant of himself and others, delighted by new horizons, Jake was always searching, searching harder than most. He also lived harder than most and was once a swinger of birches. He liked sunsets, the New World Symphony, yellow rock in the sunlight, watching his own history, cold nights, catching a fish. He was very happy in the Icefall the day he died, though he knew that mountains sometimes move.

Most of all, Jake scribed the future through his friends which imprint will survive. His friends will recognize the epitaph Jake always wanted—Long live the Crow.

—James Barry Corbet