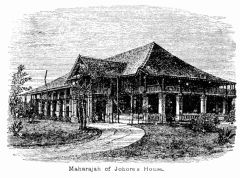

Maharajah of Johore's House

View full size illustration.

[20] Luiz de Camoens, a celebrated Portuguese poet, born about 1520; fought against the Moors, and in India; but was often in trouble, and was frequently banished or imprisoned. During his exile in Macao he wrote his great poem 'The Lusiads,' in which he celebrates the principal events in Portuguese history.

On reaching the yacht, after some delay in embarking, we slipped our anchor as quickly as possible, and soon found ourselves in a nasty rolling sea, which sent me to bed at once. Poor Tom, though he felt so ill that he could hardly hold his head up, was, however, obliged to remain on deck watching until nearly daylight; for rocks and islands abound in these seas, and no one on board could undertake the pilotage except himself.

Thursday, March 8th.—When I went on deck at half-past six o'clock there was nothing to be seen but a leaden sky, a cold grey rolling sea, and two fishing junks in the far distance, nor did the weather improve all day.

Friday, March 9th.—Everybody began to settle down to the usual sea occupations. There was a general hair-cutting all round, one of the sailors being a capital barber, and there is never time to attend to this matter when ashore. The wind was high and baffling all day. At night the Great Bear and the Southern Cross shone out with rivalling brilliancy: 'On either hand an old friend and a new.'

Saturday, March 10th.—A fine day, with a light fair breeze. Passed the island of Hainan, belonging to China, situated at the entrance of the Gulf of Tonquin, which, though very barren-looking, supports a population of 150,000.

Repacked the curiosities and purchases from Canton and Hongkong, and made up our accounts.

About noon we passed a tall bamboo sticking straight up out of the water, and wondered if it were the topmast of some unfortunate junk sunk on the Paranella Shoal. There were many flying-fish about, and the sunset was lovely.

Sunday, March 11th.—We feel that we are going south rapidly, for the heat increases day by day. The services were held on deck at eleven and four.

About five o'clock I heard cries of 'A turtle on the starboard bow,' 'A wreck on the starboard bow.' I rushed out to see what it was, and the men climbed into the rigging to obtain a better view of the object. It proved to be a large piece of wood, partially submerged, apparently about twenty or thirty feet long. The exposed part was covered with barnacles and seaweed, and there was a large iron ring attached to one end. We were sailing too fast to stop, or I should have liked to have sent a boat to examine this 'relic of the sea' more closely. These waifs and strays always set me thinking and wondering, and speculating as to what they were originally, whence they came, and all about them, till Tom declares I weave a complete legend for every bit of wood we meet floating about.

Tuesday, March 13th.—About 2.30 a.m. the main peak halyards were carried away. Soon after we gybed, and for two or three hours knocked about in the most unpleasant manner. At daybreak we made the island of Pulu Lapata, or Shoe Island, situated on the coast of Cochin China, looking snowy white in the early morning light.

The day was certainly warm, though we were gliding on steadily and pleasantly before the north-east monsoon.

Wednesday, March 14th.—The monsoon sends us along at the rate of from six to seven knots an hour, without the slightest trouble or inconvenience. There is an unexpected current, though, which sets us about twenty-five miles daily to the westward, notwithstanding the fact that a 'southerly current' is marked on the chart.

March 16th.—There was a general scribble going on all over the ship, in preparation for the post to-morrow, as we hope to make Singapore to-night, or very early in the morning. About noon Pulo Aor was seen on our starboard bow. In the afternoon, being so near the Straits, the funnel was raised and steam got up. At midnight we made the Homburgh Light, and shortly afterwards passed a large steamer steering north. It was a glorious night, though very hot below, and I spent most of it on deck with Tom, observing the land as we slowly steamed ahead half speed.

SINGAPORE.

Saturday, March 17th.—We were off Singapore during the night. At 5 a.m. the pilot came on board and took us into Tangong Pagar to coal alongside the wharf. We left the ship as soon as possible, and in about an hour we had taken forty-three tons of coal on board and nearly twenty tons of water. The work was rapidly performed by coolies. It was a great disappointment to be told by the harbour-master that the Governor of the Straits Settlement and Lady Jervoise were to leave at eleven o'clock for Johore. We determined to go straight to the Government House and make a morning call at the unearthly hour of 8 a.m. The drive from the wharf was full of beauty, novelty, and interest. We had not landed so near the line before, and the most tropical of tropical plants, trees, flowers, and ferns, were here to be seen, growing by the roadside on every bank and dust-heap.

The natives, Malays, are a fine-looking, copper-coloured race, wearing bright-coloured sarongs and turbans. There are many Indians, too, from Madras, almost black, and swathed in the most graceful white muslin garments, when they are not too hard at work to wear anything at all. The young women are very good-looking. They wear not only one but several rings, and metal ornaments in their noses, and a profusion of metal bangles on their arms and legs, which jingle and jangle as they move.

The town of Singapore itself is not imposing, its streets, or rather roads of wooden huts and stone houses, being mixed together indiscriminately. Government House is on the outskirts of the city in the midst of a beautiful park which is kept in excellent order, the green turf being closely mown and dotted with tropical trees and bushes. The House itself is large and handsome, and contains splendid suites of lofty rooms, shaded by wide verandahs, full of ferns and palms, looking deliciously green and cool. We found the Governor and his family did not start until 11.30, and they kindly begged us to return to breakfast at half-past nine, which we did. Before finally leaving, Sir William Jervoise sent for the Colonial Secretary, and asked him to look after us in his absence. He turned out to be an old schoolfellow and college friend of Tom's at Rugby and Oxford; so the meeting was a very pleasant one. As soon as the Governor and his suite had set off for Johore we went down into the hot dusty town to get our letters, parcels, and papers, and to look at the shops. There are not many Malay specialities to be bought here; most of the curiosities come from India, China, and Japan, with the exception of birds of Paradise from New Guinea, and beautiful bright birds of all colours and sizes from the various islands in the Malay Archipelago.

The north-east monsoon still blows fresh and strong, but it was nevertheless terribly hot in the streets, and we were very glad to return to the cool, shady rooms at Government House, where we thoroughly appreciated the delights of the punkah.

There are very few European servants here, and they all have their own peons to wait on them, and carry an umbrella over them when they drive the carriage or go for a walk on their own account. Even the private soldier in Singapore has a punkah pulled over his bed at night. It is quite a sight to meet all the coolies leaving barracks at 5 a.m., when they have done punkah-pulling.

At four o'clock Mr. Douglas called to take us for a drive. We went first to the Botanical Gardens, and saw sago-palms and all sorts of tropical produce flourishing in perfection. There were many beautiful birds and beasts, Argus pheasants, Lyre birds, cuckoos, doves, and pigeons, more like parrots than doves in the gorgeous metallic lustre of their plumage. The cages were large, and the enclosures in front full of Cape jasmine bushes (covered with buds) for the birds to peck at and eat.

From the gardens we went for a drive through the pretty villas that surround Singapore in every direction. Every house outside the town is built on a separate little hill in order to catch every breath of fresh air. There is generally rather a long drive up to the houses, and the public roads run along the valleys between them.

It was now dark, and we returned to dine at Government House.

Sunday, March 18th.—At six o'clock this morning Mabelle and I went ashore with the steward and the comprador to the market. It is a nice, clean, octagonal building, well supplied with vegetables and curious fruits. The latter are mostly brought from the other islands, as this is the worst season of the year in Singapore for fruit. I do not quite understand why this should be, for, as it is only a degree above the line, there is very little variation in the seasons here. The sun always rises and sets at six o'clock all the year round; for months they have a north-east monsoon, and then for months together a south-west monsoon.

We tasted many fruits new to us—delicious mangosteens, lacas, and other fruits whose names I could not ascertain. Lastly, we tried a durian, the fruit of the East, as it is called by people who live here, and having got over the first horror of the onion-like odour we found it by no means bad.

The fish market is the cleanest, and best arranged, and sweetest smelling that I ever went through. It is situated on a sort of open platform, under a thick thatched roof, built out over the sea, so that all the refuse is easily disposed of and washed away by the tide. From the platform on which it stands, two long jetties run some distance out into the sea, so that large fishing boats can come alongside and discharge their cargoes from the deep at the door of the market with scarcely any exposure to the rays of the tropical sun.

The poultry market is a curious place. On account of the intense heat everything is brought alive to the market, and the quacking, cackling, gobbling, and crowing that go on are really marvellous. The whole street is alive with birds in baskets, cages, and coops, or tied by the leg and thrown down anyhow. There were curious pheasants and jungle-fowl from Perak, doves, pigeons, quails, besides cockatoos, parrots, parrakeets, and lories. They are all very tame and very cheap; and some of the scarlet lories, looking like a flame of fire, chatter in the most amusing way. I have a cage full of tiny parrots not bigger than bullfinches, of a dark green colour, with dark red throats and blue heads, yellow marks on the back, and red and yellow tails. Having bought these, everybody seemed to think that I wanted an unlimited supply of birds, and soon we were surrounded by a chattering crowd, all with parrots in their hands and on their shoulders. It was a very amusing sight, though rather noisy, and the competition reduced the prices very much. Parrakeets ranged from twelve to thirty cents apiece, talking parrots and cockatoos from one to five dollars. At last the vendors became so energetic that I was glad to get into the gharry again, and drive away to a flower shop, where we bought some gardenias for one penny a dozen, beautifully fresh and fragrant, but with painfully short stalks.

Towards the end of the south-west monsoon, little native open boats arrive from the islands 1,500 to 3,000 miles to the southward of Singapore. Each has one little tripod mast. The whole family live on board. The sides of the boat cannot be seen for the multitudes of cockatoos, parrots, parrakeets, and birds of all sorts, fastened on little perches, with very short strings attached to them. The decks are covered with sandal-wood. The holds are full of spice, shells, feathers, and South Sea pearl shells. With this cargo they creep from island to island, and from creek to creek, before the monsoon, till they reach their destination. They stay a month or six weeks, change their goods for iron, nails, a certain amount of pale green or Indian red thread for weaving, and some pieces of Manchester cotton. They then go back with the north-east monsoon, selling their goods at the various islands on their homeward route. There are many Dutch ports nearer than Singapore, but they are over-regulated, and preference is given to the free English port, where the simple natives can do as they like so long as they do not transgress the laws.

As we were going on board, we met the Maharajah of Johore's servant, just going off with invitations to dinner, lunch, and breakfast for the next two days for all our party, and with all sorts of kind propositions for shooting and other amusements.

Some of our friends came off before luncheon to see the yacht, and we returned with them to tiffin at Government House. At four o'clock the carriage came round to take us to Johore. We wished good-bye to Singapore and all our kind friends, and started on a lovely drive through the tropical scenery. There is a capital road, fifteen miles in length, across the island, and our little ponies rattled along at a good pace. There was a pleasant breeze and not much dust, no sun, and a stream ran the whole way by the side of the road. The acacia flamboyante—that splendid tree which came originally from Rangoon and Sumatra—was planted alongside the road, and produced a most charming effect. It is a large tree, with large leaves of the most delicate green; on its topmost boughs grow gorgeous clusters of scarlet flowers with yellow centres, and the effect of these scarlet plumes tossing in the air is truly beautiful. As we were driving along we espied a splendid butterfly, with wings about ten inches long. Mr. Bingham jumped out of the carriage and knocked it down with his hat; but it was so like the colour of leaves in grass that in the twilight nobody could distinguish it, and, to our great disappointment, we could not find it. We were equally unsuccessful in our attempted capture of a water-snake a couple of feet long. We threw sticks and stones and our syce waded into the stream, but all to no purpose; it glided away into some safe little hole under the bank.

We reached the sea-shore about six o'clock, and found the Maharajah's steam-launch waiting to convey us across the Straits to the mainland. These Straits used to be the old route to Singapore, and are somewhat intricate. Tom engaged a very good pilot to bring the yacht round, but at the last moment thought that he should like to bring her himself; the result being that he arrived rather late for dinner. The Maharajah and most of the party were out shooting when we arrived; but Sir William Jervoise met us and showed us round the place, and also arranged about rooms for us to dress in. Johore is a charming place; the Straits are so narrow and full of bends that they look more like a peaceful river or inland lake in the heart of a tropical forest than an arm of the mighty ocean. As we approached we had observed a good deal of smoke rising from the jungle, and, as the shades of evening closed over the scene, we could see the lurid glare of two extensive fires.

We sat down thirty to dinner at eight o'clock. There were the Maharajah's brothers, the Prime Minister, Harkim or judge, and several other Malay chiefs, the Governor of the Straits Settlements, his family and suite, and one or two people from Singapore. The dinner was cooked and served in European style; the table decorated with gold and silver épergnes full of flowers, on velvet stands, and with heaps of small cut-flower glasses full of jasmine. We were waited on by the Malay servants of the establishment, dressed in grey and yellow, and by the Governor's Madras servants, in white and scarlet. The Maharajah and his native guests were all in English evening dress, with white waistcoats, bright turbans, and sarongs. The room was large and open on all sides, and the fresh evening breeze, in addition to the numerous punkahs, made it delightfully cool. The Maharajah is a strict Mohammedan himself, and drinks nothing but water. I spent the three hours during which the dinner lasted in very pleasant conversation with my two neighbours. We returned on board soon after eleven o'clock.

Monday, March 19th.—Mabelle and I went ashore at six o'clock for a drive. It was a glorious morning, with a delightfully cool breeze, and the excursion was most enjoyable. We drove first through the old town of Johore, once of considerable importance, and still a place of trade for opium, indigo, pepper, and other tropical products. Nutmeg and maize used to be the great articles of export, but latterly the growth has failed, and, instead of the groves we had expected to see, there were only solitary trees. After leaving the town we went along a good road for some distance, with cottages and clearings on either side, until we came to a pepper and gambir plantation. The two crops are cultivated together, and both are grown on the edge of the jungle, for the sake of the wood, which is burned in the preparation of the gambir. I confess that I had never heard of the latter substance before, but I find that it is largely exported to Europe, where it is occasionally employed for giving weight to silks, and for tanning purposes.

The pepper garden we saw was many acres in extent. Some of the trees in the forest close by are very fine, especially the camphor-wood, and the great red, purple, and copper-coloured oleanders, which grow in clumps twenty and thirty feet in height. The orchids with which all the trees were covered, hanging down in long tassels of lovely colours, or spread out like great spotted butterflies and insects, were most lovely of all. By far the most abundant was the white phalænopsis, with great drooping sprays of pure white waxy blossoms, some delicately streaked with crimson, others with yellow. It was a genuine jungle, and we were told that it is the resort of numerous tigers and elephants, and that snakes abound.

On our way back through the town we stopped to see the process of opium making. This drug is brought from India in an almost raw state, rolled up in balls, about the size of billiard balls, and wrapped in its own leaves. Here it is boiled down, several times refined, and prepared for smoking. The traffic in it forms a very profitable monopoly, which is shared in Singapore between the English Government and the Maharajah of Johore.

We also saw indigo growing; the dye is prepared very much in the same way as the gambir. That grown here is not so good as that which comes from India, and it is therefore not much exported, though it is used by the innumerable Chinese in the Malay peninsula to dye all their clothes, which are invariably of some deep shade of blue. We saw sago-palms growing, but the mill was not working, so that we could not see the process of manufacture; but it seems to be very similar to the preparation of tapioca, which we had seen in Brazil.

On our passage through the town we went to look at a large gambling establishment; of course no one was playing so early in the morning, but in the evening it is always densely crowded, and is a great source of profit to the proprietor. I could not manage to make out exactly from the description what the game they play is like, but it was not fan-tan. We now left the carriage, and strolled to see the people, the shops, and the market. I bought all sorts of common curiosities, little articles of everyday life, some of which will be sure to amuse and interest my English friends. Among my purchases were a wooden pillow, some joss candles, a two-stringed fiddle, and a few preserved eggs, which they say are over a hundred years old. The eggs are certainly nasty enough for anything; still it seems strange that so thrifty a people as the Chinese should allow so much capital to lie dormant—literally buried in the earth.

At half-past nine o'clock the Maharajah, with the Governor and all his guests, came on board. His Highness inspected the yacht with the utmost minuteness and interest, though his Mohammedan ideas about women were considerably troubled when he was told that I had had a great deal to do with the designing and arrangement of the interior. At half-past eleven the party left, and an hour afterwards we went to make our adieux to the Maharajah.

On our departure the Maharajah ordered twenty coolies to accompany us, laden with fragrant tropical plants. He also gave me some splendid Malay silk sarongs, grown, made, and woven in his kingdom, a pair of tusks of an elephant shot within a mile of the house, besides a live little beast, not an alligator, and not an armadillo or a lizard; in fact I do not know what it is; it clings round my arm just like a bracelet, and it was sent as a present by the ex-Sultan of Johore. Having said farewell to our kind host and other friends, we pushed off from the shore, and embarked on board the yacht; the anchor was up, and by five o'clock a bend in the Straits hid hospitable and pleasant Johore from our view, and all we could see was the special steamer on her way back to Singapore with the Maharajah's guests on board. At Tanjore we dropped our funny little pilot, and proceeded on our course towards Penang. The Straits are quite lovely, and fully repaid the trouble and time involved in the detour made to visit them. The sun set and the young moon arose over as lovely a tropical scene as you can possibly imagine.

Tuesday, March 20th.—At 5.30, when we were called, the Doctor came and announced that he had something very important to communicate to us. This proved to be that one of our men was suffering from small-pox, and not from rheumatic fever, as had been supposed. My first thought was that Muriel had been with the Doctor to see him yesterday evening; my next, that many men had been sleeping in the same part of the vessel with him; my third, that for his greater comfort he had been each day in our part of the ship; and my fourth, what was to be done now? After a short consultation, Tom decided to alter our course for Malacca, where we arrived at half-past nine; the Doctor at once went on shore in a native prahu to make the best arrangements he could under the circumstances. He was fortunate enough to find Dr. Simon, nephew of the celebrated surgeon of the same name, installed as head physician at the civil hospital here. He came off at once with the hospital boat, and, having visited the invalid, declared his illness to be a very mild case of small-pox. He had brought off some lymph with him, and recommended us all to be re-vaccinated. He had also brought sundry disinfectants, and gave instructions about fumigating and disinfecting the yacht. All the men were called upon the quarter-deck, and addressed by Tom, and we were surprised to find what a large proportion of them objected to the operation of vaccination. At last, however, the prejudices of all of them, except two, were overcome. One of the latter had promised his grandfather that he never would be vaccinated under any circumstances, while another would consent to be inoculated, but would not be vaccinated. We had consulted our own medical man before leaving England, and knew that for ourselves the operation was not necessary, but we nevertheless underwent it pour encourager les autres. While the Doctor was on shore we had been surrounded by boats bringing monkeys, birds, ratan and Malacca canes, fruit, rice, &c., to sell, and as I did not care to go ashore, thinking there might be some bother about quarantine, we made bargains over the side of the yacht with the traders, the result being that seven monkeys, about fifty birds of sorts, and innumerable bundles of canes, were added to the stock on board. In the meantime Dr. Simon had removed our invalid to the hospital.

Malacca looks exceedingly pretty from the sea. It is a regular Malay village, consisting of huts, built on piles close to the water, overshadowed by cocoa palms and other forms of tropical vegetation. Mount Ofia rises in the distance behind; there are many green islands, too, in the harbour. By one o'clock we were again under way, and once more en route for Penang.

Wednesday, March 21st.—During the night we had heavy thunder storms. About 11 a.m. we passed a piece of drift-wood with a bird perched on the top, presenting a most curious effect. Several of the men on board mistook it for the back fin of a large shark. About 5 p.m. we made the island of Penang. After sunset it became very hazy, and we crept slowly up, afraid of injuring the numerous stake nets that are set about the Straits most promiscuously, and without any lights to mark their position. Before midnight we had dropped our anchor.

Thursday, March 22nd.—At 5 a.m., when we were called, the whole sky was overcast with a lurid glare, and the atmosphere was thick, as if with the fumes of some vast conflagration. As the sun rose in raging fierceness, the sky cleared, and became of a deep, clear, transparent blue. The island of Penang is very beautiful, especially in the early morning light. It was fortunate we did not try to come in last night, as we could now see that we must inevitably have run through some of the innumerable stake nets I mentioned. As we approached Georgetown, the capital of the province, we passed many steamers and sailing ships at anchor in the roads. A pilot offered his services, but Tom declined them with thanks, and soon afterwards skilfully brought us up close in shore in the crowded roadstead. The harbour-master sent off, as did also the mail-master, but no Board of Health officials appeared; so, after some delay, the Doctor went on shore to find the local medical man, promising shortly to return. He did not, however, reappear, and, after waiting a couple of hours, we landed without opposition. We packed off all the servants for a run on shore, and had all the fires put out in order to cool the ship. Our first inquiry was for an hotel where we could breakfast, and we were recommended to go to the Hôtel de l'Europe.

Our demands for breakfast were met at first with the reply that it was too late, and that we must wait till one o'clock tiffin; but a little persuasion induced the manager to find some cold meat, eggs, and lemonade. We afterwards drove out to one or two shops, but anything so hopeless as the stores here I never saw. Not a single curiosity could we find, not even a bird. We drove round the town, and out to the Governor's house; he was away, but we were most kindly received by Mrs. Anson and his daughter, and strongly recommended by them to make an expedition to the bungalow at the top of the hill. In about an hour and a half, always ascending, we reached the Governor's bungalow, situated in a charming spot, where the difference of 10° in the temperature, caused by being 1,500 feet higher up, is a great boon. After tiffin and a rest at the hotel, a carriage came to take us to the foot of the hill, about four miles from the town. We went first to a large Jesuit establishment, where some most benevolent old priests were teaching a large number of Malay boys reading, writing, and geography. Then we went a little further, and, in a small wooden house, under the cocoa trees, at last found some of the little humming birds for which the Malay Archipelago is famous. They glisten with a marvellous metallic lustre all over their bodies, instead of only in patches, as one sees upon those in South America and the West Indies. The drive was intensely tropical in character, until we reached the waterfall, where we left the carriage and got into chairs, each carried by six coolies. The scenery all about the waterfall is lovely, and a large stream of sparkling, cool, clear water tumbling over the rocks was most refreshing to look at. Many people who have business in Penang live up here, riding up and down morning and evening, for the sake of the cool, refreshing night air. One of the most curious things in vegetation which strikes our English eyes is the extraordinary abundance of the sensitive plant. It is interwoven with all the grass, and grows thickly in all the hedgerows. In the neatly kept turf, round the Government bungalow, its long, creeping, prickly stems, acacia-like leaves, and little fluffy mauve balls of flowers are so numerous, that, walking up and down the croquet lawn, it appears to be bowing before you, for the delicate plants are sensible of even an approaching footstep, and shut up and hide their tiny leaves among the grass long before you really reach them.

From the top of the hill you can see ninety miles in the clear atmosphere, far away across the Straits of Perak to the mainland. We could not stay long, and were carried down the hill backwards, as our bearers were afraid of our tumbling out of the chairs if we travelled forwards. The tropical vegetation is even more striking here, but, alas! it is already losing its novelty to us. Those were indeed pleasant days when everything was new and strange; it seems now almost as if years, not months, had gone past since we first entered these latitudes. We found the carriage waiting for us when we arrived at the bottom of the hill about seven o'clock, and it was not long before we reached the town.

The glowworms and fireflies were numerous. The natives were cooking their evening meal on the ground beneath the tall palm-trees as we passed, with the glare of the fires lighting up the picturesque huts, their dark figures relieved by their white and scarlet turbans and waist-cloth. The whole scene put us very much in mind of the old familiar pictures of India, the lithe figures of the natives looking like beautiful bronze statues, the rough country carts, drawn by buffaloes without harness, but dragging by their hump, and driven by black-skinned natives armed with a long goad. We went straight to the jetty, and found to our surprise that in the roads there was quite a breeze blowing, and a very strong tide running against it, which made the sea almost rough.

Mrs. and Miss Anson, Mr. Talbot, and other friends, dined with us. At eleven they landed, and we weighed anchor, and were soon gliding through the Straits of Malacca, shaping for Acheen Head, en route to Galle.

It seems strange that an important English settlement like Penang, where so many large steamers and ships are constantly calling, should be without lights or quarantine laws. We afterwards learned on shore that the local government had already surveyed and fixed a place for two leading lights. The reason why no health officers came off to us this morning was probably that, small-pox and cholera both being prevalent in the town, they thought that the fewer questions they asked, and the less they saw of incoming vessels, the better.

Friday, March 23rd.—A broiling day, everybody panting, parrots and parrakeets dying. We passed a large barque with every sail set, although it was a flat calm, which made us rejoice in the possession of steam-power. Several people on board are very unwell, and the engineer is really ill. It is depressing to speculate what would become of us if anything went wrong in the engine-room department, and if we should be reduced to sail-power alone in this region of calmness. At last even I know what it is to be too hot, and am quite knocked up with my short experience.

Saturday, March 24th.—Another flat calm. The after-forecastle, having been battened down and fumigated for the last seventy-two hours, was to-day opened, and its contents brought up on deck, some to be thrown overboard, and others to be washed with carbolic acid. I never saw such quantities of things as were turned out; they covered the whole deck, and it seemed as if their cubic capacity must be far greater than that of the place in which they had been stowed. Besides the beds and tables of eight men, there were forty-eight birds, four monkeys, two cockatoos, and a tortoise, besides Japanese cabinets and boxes of clothes, books, china, coral, shells, and all sorts of imaginable and unimaginable things. One poor tortoise had been killed and bleached white by the chlorine gas.

Sunday, March 25th.—Hotter than ever. It was quite impossible to have service either on deck or below. We always observe Sunday by showing a little extra attention to dress, and, as far as the gentlemen are concerned, a little more care in the matter of shaving. On other days I fear our toilets would hardly pass muster in civilised society. Tom set the example of leaving off collars, coats, and waistcoats; so shirts and trousers are now the order of the day. The children wear grass-cloth pinafores and very little else, no shoes or stockings, Manilla or Chinese slippers being worn by those who dislike bare feet. I find my Tahitian and Hawaiian dresses invaluable: they are really cool, loose, and comfortable, and I scarcely ever wear anything else.

We passed a large steamer about 7.30 a.m., and in the afternoon altered our course to speak the 'Middlesex,' of London, bound to the Channel for orders. We had quite a long conversation with the captain, and parted with mutual good wishes for a pleasant voyage. It was a lovely moonlight night, but very hot, though we found a delightful sleeping-place beneath the awning on deck.

Monday, March 26th.—The sun appeared to rise even fiercer and hotter than ever this morning. I have been very anxious for the last few days about Baby, who has been cutting some teeth and has suffered from a rash. Muriel has been bitten all over by mosquitoes, and Mabelle has also suffered from heat-rash. Just now every little ailment suggests small-pox to our minds.

About noon, when in latitude 6.25 North, and in longitude 88.25 East, we began to encounter a great deal of drift wood, many large trees, branches, plants, leaves, nautilus shells, back-bones of cuttlefish, and, in addition, large quantities of yellow spawn, evidently deposited by some fish of large size. The spawn appeared to be of a very solid, consistent character, like large yellow grapes, connected together in a sort of gelatinous mass. It formed a continuous wide yellow streak perhaps half a mile in length, and with the bits of wood and branches sticking up in its midst at intervals, it would not have required a very lively imagination to fashion it at a little distance into a sea serpent. Where does all this débris come from? was the question asked by everybody. Out of the Bay of Bengal probably, judging from the direction of the current. We wondered if it could possibly be the remains of some of the trees uprooted by the last great cyclone.

At 1.30 p.m. a man cried out from the rigging, 'Boat on the starboard bow!' a cry that produced great excitement immediately; our course was altered and telescopes and glasses brought to bear upon the object in question. Every one on board, except our old sailing master, said it was a native boat. Some even said that they could see a man on board waving something. Powell alone declared it to be the root of a palm from the Bay of Bengal, and he proved right. A very large root it was, with one single stem and a few leaves hanging down, which had exactly the appearance of broken masts, tattered sails, and torn rigging. We went close alongside to have a good look at it; the water was as clear as crystal, and beneath the surface were hundreds of beautifully coloured fish, greedily devouring something—I suppose small insects, or fish entangled among the roots.

Tuesday, March 27th.—It requires a great effort to do anything, except before sunrise or after sunset, owing to the intense heat; and when one is not feeling well it makes exertion still more difficult. At night the heat below is simply unbearable; the cabins are deserted, and all mattresses are brought up on deck.

CEYLON.

Wednesday, March 28th.—At midnight the wind was slightly ahead, and we could distinctly smell the fragrant breezes and spicy odours of Ceylon. We made the eastern side of the island at daylight, and coasted along its palm-fringed shores all day. I had been very unwell for some days past, but this delightful indication of our near approach to the land seemed to do me good at once. If only the interior is as beautiful as what we can see from the deck of the yacht, my expectations will be fully realised, brilliant as they are.

As the sun set, the beauty of the scene from the deck of the yacht seemed to increase. We proceeded slowly, and at about nine o'clock were in the roads of Galle and could see the ships at anchor. Tom did not like to venture further in the dark without a pilot, and accordingly told the signal-man to make signals for one, but being impatient he sent up a rocket, besides burning blue lights, a mistake which had the effect of bringing the first officer of the P. and O. steamship 'Poonah' on board, who thought perhaps we had got aground or were in trouble of some sort. He also informed us that pilots never came off after dark, and kindly offered to show us a good anchorage for the night.

Thursday, March 29th.—The pilot came off early, and soon after six we dropped anchor in Galle harbour. The entrance is fine, and the bay one of the most beautiful in the world. The picturesque town, with its old buildings, and the white surf dashing in among the splendid cocoa-trees which grow down to the water's edge, combined to make up a charming picture. We went on board the 'Poonah' to breakfast as arranged, and afterwards all over the ship, which is in splendid order. Thence we went ashore to the Oriental Company's Hotel, a most comfortable building, with a large, shady verandah, which to-day was crowded by passengers from the 'Poonah.' At tiffin there was a great crowd, and we met some old friends. At three o'clock we returned to the yacht, to show her to the captain of the 'Poonah' and some of his friends, and an hour later we started in two carriages for a drive to Wockwalla, a hill commanding a splendid view. The drive was delightful, and the vegetation more beautiful than any we have seen since leaving Tahiti, but it would have been more enjoyable if we had not been so pestered by boys selling flowers and bunches of mace in various stages of development. It certainly is very pretty when the peach-like fruit is half open and shows the network of scarlet mace surrounding the brown nutmeg within. From Wockwalla the view is lovely, over paddy-fields, jungle, and virgin forest, up to the hills close by and to the mountains beyond. There is a small refreshment-room at the top of the hill, kept by a nice little mulatto woman and her husband. Here we drank lemonade, ate mangoes, and watched the sun gradually declining, but we were obliged to leave before it had set, as we wanted to visit the cinnamon gardens on our way back. The prettiest thing in the whole scene was the river running through the middle of the landscape, and the white-winged, scarlet-bodied cranes, disporting themselves along the banks among the dark green foliage and light green shoots of the crimson-tipped cinnamon-trees. We had a glorious drive home along the sea-shore under cocoa-nut trees, amongst which the fireflies flitted, and through which we could see the red and purple afterglow of the sunset. Ceylon is, as every one knows, celebrated for its real gems, and almost as much for the wonderful imitations offered for sale by the natives. Some are made in Birmingham and exported, but many are made here and in India, and are far better in appearance than ours, or even those of Paris. More than once in the course of our drive, half-naked Indians produced from their waist-cloths rubies, sapphires, and emeralds for which they asked from one to four thousand rupees, and gratefully took fourpence, after a long run with the carriage, and much vociferation and gesticulation. After table-d'hôte dinner at the hotel we went off to the yacht in a pilot boat; the buoys were all illuminated, and boats with four or five men in them, provided with torches, were in readiness to show us the right way out. By ten o'clock we were outside the harbour and on our way to Colombo.

Friday, March 30th.—It rained heavily during the night, and we were obliged to sleep in the deck-house instead of on deck. At daylight all was again bright and beautiful, and the cocoanut-clad coast of Ceylon looked most fascinating in the early morning light. About ten o'clock we dropped our anchor in the harbour at Colombo, which was crowded with shipping. 175,000 coolies have been landed here within the last two or three months; consequently labour is very cheap this year in the coffee plantations.

The instant we anchored we were of course surrounded by boats selling every possible commodity and curiosity, carved ebony, ivory, sandal-wood, and models of the curious boats in use here. These boats are very long and narrow, with an enormous outrigger and large sail, and when it is very rough, nearly the whole of the crew of the boat go out one by one, and sit on the outrigger to keep it in the water, from which springs the Cingalese saying, 'One man, two men, four men breeze.' The heat was intense, though there was a pleasant breeze under the awning on deck; we therefore amused ourselves by looking over the side and bargaining with the natives, until our letters, which we had sent for, arrived. About one o'clock we went ashore, encountering on our way some exceedingly dreadful smells, wafted from ships laden with guano, bones, and other odoriferous cargoes. The inner boat harbour is unsavoury and unwholesome to the last degree, and is just now crowded with many natives of various castes from the south of India.

Colombo is rather a European-looking town, with fine buildings and many open green spaces, where there were actually soldiers playing cricket, with great energy, under the fierce rays of the midday sun. We went at once to an hotel and rested; loitering after tiffin in the verandah, which was as usual crowded with sellers of all sorts of Indian things. Most of the day was spent in driving about, and having made our arrangements for an early start to-morrow, we then walked down to the harbour, getting drenched on our way by a tremendous thunderstorm.

Saturday, March 31st.—Up early, and after rather a scramble we went ashore at seven o'clock, just in time to start by the first train to Kandy. There was not much time to spare, and we therefore had to pay sovereigns for our tickets instead of changing them for rupees, thereby receiving only ten instead of eleven and a half, the current rate of exchange that day. It seemed rather sharp practice on the part of the railway company (alias the Government) to take sovereigns in at the window at ten rupees, and sell them at the door for eleven and a half, to speculators waiting ready and eager to clutch and sell them again at an infinitesimally small profit.

The line to Kandy is always described as one of the most beautiful railways in the world, and it certainly deserves the character. The first part of the journey is across jungle and through plains; then one goes climbing up and up, looking down on all the beauties of tropical vegetation, to distant mountains shimmering in the glare and haze of the burning sun. The carriages were well ventilated and provided with double roofs, and were really tolerably cool.

About nine o'clock we reached Ambepussa, and the scenery increased in beauty from this point. A couple of hours later we reached Peradeniya, the junction for Gampola. Here most of the passengers got out, bound for Neuera-ellia, the sanatorium of Ceylon, 7,000 feet above the sea. Soon after leaving the station, we passed the Satinwood Bridge. Here we had a glimpse of the botanical garden at Kandy, and soon afterwards reached the station. We were at once rushed at by two telegraph boys, each with a telegram of hospitable invitation, whilst a third friend met us with his carriage, and asked us to go at once to his house, a few miles out of Kandy. We hesitated to avail ourselves of his kind offer, as we were such a large party; but he insisted, and at once set off to make things ready for us, whilst we went to breakfast and rest at a noisy, dirty, and uncomfortable hotel. It was too hot to do anything except to sit in the verandah and watch planter after planter come in for an iced drink at the bar. The town is quite full for Easter, partly for the amusements and partly for the Church services; for on many of the coffee estates there is no church within a reasonable distance.

About four o'clock the carriage came round for us, and having despatched the luggage in a gharry, we drove round the lovely lake, and so out to Peradeniya, where our friend lives, close to the Botanic Gardens. Many of the huts and cottages by the roadside have 'small-pox' written upon them in large letters, in three languages, English, Sanscrit, and Cingalese, a very sensible precaution, for the natives are seldom vaccinated, and this terrible disease is a real scourge amongst them. Having reached the charming bungalow, it was a real luxury to lounge in a comfortable easy chair in a deep cool verandah, and to inhale the fragrance of the flowers, whilst lazily watching the setting of the sun. Directly it dipped below the horizon, glowworms and fireflies came out, bright and numerous as though the stars had come down to tread, or rather fly, a fairy dance among the branches of the tall palm-trees high overhead. Our rooms were most comfortable, and the baths delicious. After dinner we all adjourned once more to the verandah to watch the dancing fireflies, the lightning, and the heavy thunderclouds, and enjoy the cool evening breeze. You in England who have never been in the tropics cannot appreciate the intense delight of that sensation. Then we went to bed, and passed a most luxurious night of cool and comfortable sleep, not tossing restlessly about, as we had been doing for some time past.

Sunday, April 1st.—I awoke before daylight. Our bed faced the windows, which were wide open, without blinds, curtains, or shutters, and I lay and watched the light gradually creeping over the trees, landscape, and garden, and the sun rising glorious from behind the distant mountains, shining brightly into the garden, drawing out a thousand fresh fragrances from every leaf and flower.

By seven o'clock we found ourselves enjoying an early tea within the pretty bungalow in the centre of the Botanic Gardens, and thoroughly appreciating delicious fresh butter and cream, the first we have tasted for ages. We went for the most delightful stroll afterwards, and saw for the first time many botanical curiosities, and several familiar old friends growing in greater luxuriance than our eyes are even yet accustomed to. The groups of palms were most beautiful. I never saw anything finer than the tallipot-palm, and the areca, with the beetle-vine climbing round it; besides splendid specimens of the kitool or jaggery-palm. Then there was the palmyra, which to the inhabitant of the North of Ceylon is what the cocoa-nut is to the inhabitant of the South—food, clothing, and lodging. The pitcher-plants and the rare scarlet amherstia looked lovely, as did also the great groups of yellow and green stemmed bamboos. There were magnolias, shaddocks, hibiscus, the almost too fragrant yellow-flowered champac, sacred to Hindoo mythology; nutmeg and cinnamon trees, tea and coffee, and every other conceivable plant and tree, growing in the wildest luxuriance. Through the centre of the gardens flows the river Ambang Ganga, and the whole 140 acres are laid out so like an English park that, were it not for the unfamiliar foliage, you might fancy yourself at home.

We drove back to our host's to breakfast, and directly afterwards started in two carriages to go to church at Kandy. The church is a fine large building, lofty, and cool, and well ventilated. This being Easter Sunday, the building was lavishly decorated with palms and flowers. The service was well performed, and the singing was excellent. The sparrows flew in and out by the open doors and windows. One of the birds was building a nest in a corner, and during the service she added to it a marabout feather, a scrap of lace, and an end of pink riband. It will be a curious nest when finished, if she adds at this rate to her miscellaneous collection.

After church we walked to the Government House. Sir William Gregory is, unfortunately for us, away in Australia, and will not return till just after our departure. The entrance to it was gay with gorgeous scarlet lilies, brought over by some former Governor from South America. It is a very fine house, but unfinished. We wandered through the 'banquet halls deserted,' and then sat a little while in the broad cool airy verandah looking into the beautiful garden and on to the mountain beyond.

At half-past eleven it was time to leave this delightfully cool retired spot, and to drive to a very pleasant luncheon, served on a polished round walnut-wood table, without any tablecloth, a novel and pretty plan in so hot a climate. As soon as it became sufficiently cool we went on round the upper lake and to the hills above, whence we looked down upon Kandy, one of the most charmingly placed cities in the world. As we came back we stopped for a few minutes at the Court, a very fair specimen of florid Hindoo architecture, where the judges sit, and justice of all kinds is administered, and where the Prince of Wales held the installation of the Order of St. Michael and St. George during his visit. We also looked in at some of the bazaars, to examine the brass chatties and straw-work. Then came another delicious rest in the verandah among the flowers until it was time for dinner. Such flowers as they are! The Cape jessamines are in full beauty just now, and our host breaks off for us great branches laden with the fragrant bloom.

Monday, April 2nd.—Before breakfast I took a stroll all round the place, with our host, to look at his numerous pets, which include spotted deer, monkeys, and all sorts of other creatures. We also went to the stables, and saw first the horses, and the horsekeepers with their pretty Indian wives and children. Then we wandered down to the bamboo-fringed shores of the river, which rises in the mountains here, and flows right through the island to Trincomalee.

At eleven o'clock Tom and I said 'good-bye' to the rest of the party, and went by train to Gampola, to take the coach to Neuera-ellia, where we were to stay with an old friend. We went only a dozen miles in the train, and then were turned out into what is called a coach, but is really a very small rough wagonnette, capable of holding six people with tolerable comfort, but into which seven, eight, and even nine were crammed. By the time the vehicle was fully laden, we found there was positively no room for even the one box into which Tom's things and my own had all been packed; so we had to take out indispensable necessaries, and tie them up in a bundle like true sailors out for a holiday, leaving our box behind, in charge of the station-master, until our return. The first part of the drive was not very interesting, the road passing only through paddy-fields and endless tea and coffee plantations. We reached Pusillawa about two o'clock, where we found a rough and ready sort of breakfast awaiting us. Thence we had a steep climb through some of the finest coffee estates in Ceylon, belonging to the Rothschilds, until we reached Rangbodde. Here there was another delay of half an hour; but although we were anxious to get on, to arrive in time for dinner, it was impossible to regret stopping amidst this lovely scenery. The house which serves as a resting-place is a wretched affair, but the view from the verandah in front is superb. A large river falls headlong over the steep wall of rock, forming three splendid waterfalls, which, uniting and rushing under a fine one-arched bridge, complete this scene of beauty and grandeur.

We were due at Neuera-ellia at six, but we had only one pair of horses to drag our heavy load up the steep mountain road, and the poor creatures jibbed, kicked over the traces, broke them three times, and more than once were so near going over the edge of the precipice that I jumped out, and the other passengers, all gentlemen, walked the whole of that stage. The next was no better, the fresh pair of horses jibbing and kicking worse than ever. At last one kicked himself free of all the harness, and fell on his back in a deep ditch. If it had not been so tiresome, it really would have been very laughable, especially as everybody was more or less afraid of the poor horse's heels, and did not in the least know how to extricate him.

In this dilemma our hunting experiences came in usefully, for with the aid of a trace, instead of a stirrup leather, passed round his neck, half-a-dozen men managed to haul the horse on to his legs again; but the pitchy darkness rendered the repair of damages an exceedingly difficult task. The horses, moreover, even when once more in their proper position, declined to move, but the gentlemen pushed and the drivers flogged and shouted, and very slowly and with many stops we ultimately reached the end of that stage. Here we found a young horse, who had no idea at all of harness; so after a vain attempt to utilise his services, another was sent for, thus causing further delay.

It was now nine o'clock, and we were all utterly exhausted. We managed to procure from a cottage some new-laid eggs and cold spring water, and these eaten raw, with a little brandy from a hunting-flask, seemed to refresh us all. There was again a difficulty in starting, but, once fairly under way, the road was not so steep and the horses went better. I was now so tired, and had grown so accustomed to hairbreadth escapes, that, however near we went to the edge of the precipice, I did not feel capable of jumping out, but sat still and watched listlessly, wondering whether we should really go over or not. After many delays we reached Head-quarter House, where the warmth of the welcome our old friend gave us soon made us forget how tired we were. They had waited dinner until half-past seven, and had then given us up. There were blazing wood fires both in the drawing-room and in our bedroom, and in five minutes a most welcome dinner was put before us. Afterwards we could have stayed and chatted till midnight, but we were promptly sent off to bed, and desired to reserve the rest of our news until morning.

Tuesday, April 3rd.—A ten o'clock breakfast afforded us ample opportunity for a delicious rest and letter-writing beforehand. Afterwards we strolled round the garden, full of English flowers, roses, carnations, mignonette, and sweet peas. Tom and the gentlemen went for a walk, whilst we ladies rested and chatted and wrote letters.

After lunch we all started—a large party—to go to the athletic sports on the racecourse, where an impromptu sort of grand stand had been erected—literally a stand, for there were no seats. There were a great many people, and the regimental band played very well. To us it appeared a warm damp day, although the weather was much cooler than any we have felt lately. This is the week of the year, and everybody is here from all parts of the island. People who have been long resident in the tropics seem to find it very cold; for the men wore great-coats and ulsters, and many of the ladies velvet and sables, or sealskin jackets. On the way back from the sports we drove round to see something of the settlement; it cannot be called a town, for though there are a good many people and houses, no two are within half a mile of one another. There are two packs of hounds kept here, one to hunt the big elk, the other a pack of harriers. The land-leeches, which abound in this neighbourhood, are a great plague to horses, men, and hounds. It rained last night, and I was specially cautioned not to go on the grass or to pick flowers, as these horrid creatures fix on one's ankle or arm without the slightest warning. I have only seen one, I am thankful to say, and have escaped a bite; but everybody seems to dread and dislike them.

After dinner we went to a very pleasant ball, given by the Jinkhana Club, at the barracks. The room was prettily decorated with the racing jackets and caps of the riders in the races, and with scarlet wreaths of geranium and hibiscus mingled with lycopodium ferns and selaginella. We did not remain very late at the ball, as we had to make an early start next morning; but the drive home in the moonlight was almost as pleasant as any part of the entertainment.

Wednesday, April 4th.—We were called at four o'clock, and breakfasted at five, everybody appearing either in dressing-gowns or in habits to see us set off. They all tried to persuade us to stay for the meet of the hounds at the house to-day. Another ball to-night, and more races, and another ball to-morrow; but we are homeward bound, and must hurry on. It was a lovely morning, and we waited with great patience at the post-house for at least an hour and a half, and watched the hounds come out, meet, find, and hunt a hare up and down, and across the valley, with merry ringing notes that made us long to be on horseback.

We saw all the racehorses returning from their morning gallop, and were enlightened by the syces as to their names and respective owners. There were several people, a great deal of luggage, and, though last not least, Her Majesty's mails, all waiting, like us, for the coach. About a quarter to seven a message arrived, to the effect that the horses would not come up the hill, they had been jibbing for more than an hour, so would we kindly go down to the coach. A swarm of coolies immediately appeared from some mysterious hiding-place, and conveyed us all, bag and baggage, down the hill, and packed us into the coach. Even this concession on our part did not induce the horses to make up their minds to move for at least another quarter of an hour. Then we had to stop at the hotel to pick up somebody else; but at last we had fairly started, eleven people in all, some inside and some perched on a box behind. The horses were worse than ever, tired to death, poor things; and as one lady passenger was very nervous and insisted on walking up all the acclivities, we were obliged to make up our pace down the hills. The Pass looked lovely by daylight, and the wild flowers were splendid, especially the white datura and scarlet rhododendron trees, which were literally covered with bloom.

By daylight, the appearance of the horses was really pitiable in the extreme—worn-out, half-starved wretches, covered with wounds and sores from collars and harness, and with traces of injuries they inflict on themselves in their struggles to get free. When once we had seen their shoulders, we no longer wondered at their reluctance to start; it really made one quite sick to think even of the state they were in.

If some of the permanent officials were to devote a portion of their time to endeavours to introduce American coaches, and to ameliorate the condition of the horses on this road, they would indeed confer a boon on their countrymen. The coachman, who was as black as jet, and who wore very little clothing, was a curious specimen of his class, and appeared by no means skilled in his craft. He drove the whole way down the steep zigzag road with a loose rein; at every turn the horses went close to the precipice, but were turned in the very nick of time by a little black boy who jumped down from behind and pulled them round by their traces without touching the bridle. We stopped at Rangbodde to breakfast, and again at Pusillawa. This seemed a bad arrangement, for we were already late; it resulted in the poor horses having to be unmercifully flogged in order to enable us to catch the train at Gampola, failing which, the coach proprietors would have had to pay a very heavy penalty.

From Gampola we soon arrived at Peradeniya, where we met Mr. Freer, who was going down to Colombo. Tom had decided previously to go straight on, so as to have the yacht quite ready for an early start to-morrow. I in the meantime went to our former hosts for one night to pick up Mabelle and the waifs and strays of luggage.

On my way from the station to the house, going over the Satinwood Bridge, from which there is a lovely view of the Peacock Mountain, I saw an Englishman whom we had observed before, washing stones in the bed of the river for gems. He has obtained some rubies and sapphires, though only of small size, and I suppose he will go on washing for ever, hoping to find something larger and more valuable. On one part of the coast of the island near Managgan the sands on the side of one of the rivers are formed of rubies, sapphires, garnets, and other precious stones washed down by the current, but they are all ground to pieces in the process, not one being left as big as a pin's head. The effect in the sunlight, when this sand is wet with the waves, is something dazzling, and proves that the accounts of my favourite Sindbad are not so fabulous as we prosaic mortals try to make out. The island must be rich in gems, for they seem to be picked up with hardly any trouble. At Neuera-ellia it is a favourite amusement for picnic parties to go out gem-hunting, and frequently they meet with very large and valuable stones by the riverside or near deserted pits, large garnets, cinnamon-stone, splendid cat's-eyes, amethysts, matura diamonds, moonstone, aquamarine, tourmaline rubies, and sapphires.