11

The Darkening of the Sun

The earthquake under the sea—The Chaldean announces that the day of destruction has come—The escape of the people of Gebal—The catastrophic eruption of Thira takes place—The return of Aleph—A prophecy of the greatness of the Phoenician people

The King of Gebal was sitting in a small room of the palace, overlooking the sea and the whole line of coast from north to south. He was talking to a prisoner who stood in chains, flanked by two palace guards.

“General Zayin knows me,” the man was saying. “I was his staff-sergeant in the expeditionary force he led up north. We were captured together, then I lost sight of him. They say he escaped. Me, I was taken to Carchemish, and then to Nineveh. And all the time I was prisoner they were preparing for war. Or maybe they’re always like that, the Mitanni. Keen soldiers all right, even if it is all chariots. So when the time came to invade the coast here, they wanted me as a guide, knowing I was a Giblite. What could I do, Your Majesty? I thought maybe I could lose them somewhere, mislead them like. Anyway, I was with the leading unit. Chariots it was, mainly. Ugh! No way for a soldier to travel—give me two feet any time—”

“So you guided the enemy to our land?” interjected the King harshly.

“I tell you, sir, it wasn’t a case of doing that. It was as big a shock to me as it was to them when we came across the Giblite army waiting for us that far north. The first battle was a victory for us—I mean the Giblites of course. The Mitanni were beaten back, and ran. Now’s my chance to go over to my own people, I thought. But no, they kept an eye on me and I couldn’t escape. We followed them, that is the Giblites followed the Mitanni, me still being a prisoner, but that was the mistake, to go after the Mitanni on to the open plains. I reckon if General Zayin had been there he wouldn’t have allowed it. Once in the open, the reinforcements came up, chariotry, of course, and our lot—the Giblites that is—was split up and cut to pieces—they didn’t stand a chance, foot soldiers against horse on the plains.” There were tears in the sergeant’s eyes as he said this.

“Well, then we regrouped and marched south—the Mitanni that is, and me their prisoner. I swear I didn’t help them, Your Majesty! As soon as I started recognizing the ground I gave them the slip one night in the mountains—and here I am. Lucky it’s slow going for chariots down the coast and I kept ahead of them. If I’ve had two hours’ sleep the last five nights call me a liar! But I’m not that far ahead, Your Majesty. They’ll be on us any time now, and there’s not a Giblite soldier between them and the city.”

The King pulled at his beard and spoke as if to himself. “How do I know you are telling the truth? How do I know you are not sent by the enemy to spread tales to alarm us? How do I know who you are?”

“I am no spy, Your Majesty!” the soldier protested. “Where’s General Zayin? He knows me! Ask him!” And at that moment a man strode into the room and the soldier looked hopefully into his face, thinking to recognize the features of Zayin. But it was not Zayin, though the face bore some resemblance. It was Nun, the sailor.

Nun made his obeisance to the King, and before he rose the King asked flatly, “Well, what is the news from the sea? Is it victory or defeat?”

“Neither, as yet, Your Majesty,” said Nun. “You know we set out with a small force of ships to patrol the coast to the north and south. Much as we expected, I spied the Cretan ships lying up for the night in a safe bay. They are a strong fleet. We stood in to land, trying to lure them into the open sea to do battle, and three fast rowing galleys came out to engage us. But night was falling and only one had the courage to brave the sea and the darkness. We boarded her and took prisoners. They say their fleet carries many soldiers, and their intention is to attack our city and destroy it without mercy. Your Majesty, they may be here within hours. We must have all the ships and all the troops available, and we must meet them at sea and fight there!”

The King looked grimly out to sea. “You may have the ships. As for the men, I think there are none left in Gebal.”

There was the sound of approaching feet in the corridor, and Zayin arrived, breathless and sweating.

“Is it victory or defeat?” the King asked, not waiting for Zayin to kneel.

“Victory, Your Majesty!” replied Zayin. “We repulsed the Egyptians with many casualties. But why have you ordered us to retire?”

The King looked no happier, and seemed to be talking to himself. “So, many Egyptians have been killed. It might have been better to have received them with open arms, and had Pharaoh as our friend.”

Zayin stood dumb, incredulous that the news of his victory should be received in this way. “But, Your Majesty!” he said at last. “They came to destroy us! Your orders were to—”

The King was on his feet, looking out to sea, with his back to the men in the room. He interrupted Zayin’s words. “The Egyptians have come to destroy us. The Mitanni have come to destroy us. The Cretans have come to destroy us. The gods know whether these three great empires have conspired together to annihilate our city, or whether it is only a cruel joke of Fate that they come all at one time. But what can one city do against an empire, let alone three! We cannot sit and await destruction. We have fought, and shown our mettle. The time has now come to talk terms. Send for the High Priest.”

The High Priest had been lurking near by and it did not take long for him to come. The King turned to him. “High Priest, the three great empires of the world are set on destroying us. What is your counsel?”

The High Priest had his plan ready. “Your Majesty, we must, of course, make peace with Pharaoh, as I have always said. His gods are ours, his learning is ours. He will protect us against our other enemies.”

Zayin interrupted, “How can you make peace with an army of soldiers who want nothing but vengeance for their defeat?”

“There are customs,” said the High Priest. “They must be met by an embassy of peace. Gold and jewels must be sent as gifts, and before them must go the maidens of the city and of the Temple, singing and dancing to show that they mean peace.”

Nun spoke slowly, “So we are to send our maidens to take the brunt, since our men cannot do so? And do we ever see our young women again?”

“Have you seen the desert wolves that make up the army of Pharaoh, High Priest?” cried Zayin. “Our soldiers were frightened to look at them. Are we then to send our sisters to cope with them?” Both Zayin and Nun were thinking of Beth.

“It is a custom,” shrugged the High Priest. “If we seek peace, we must purchase it.”

All looked at the King for a decision, but the King was looking out to sea, and his face told them nothing. Nun’s eyes, too, turned to the western horizon, expecting the sight of Cretan sails. Zayin moved to catch a possible glimpse of his army returning from the coast and perhaps of the pursuing Egyptians. The sergeant looked grimly northward.

What they saw—and not one of them at first believed his eyes, for each thought it was only an image of his sinking hopes—what they saw was the sea in retreat from the coast.

Quite smoothly and quietly, the calm sea was sinking. On the coast, great stretches of sand and weed-covered rocks were appearing, which had never emerged above tide level before. The water of the harbor was running out of the harbor mouth like a river, leaving a sight never previously seen on this almost tideless coast: ships lying over on their sides in the mud, timbers of sunken vessels and broken stone columns emerging from the green slime.

The four men turned and looked at each other, and knew that they had each seen the same thing. And then for a few moments it seemed as if a giant hand had taken the whole palace and shaken it until it quivered, so that pillars rocked upon their pedestals and great stones in the walls ground one against another. Each of them stood petrified, only their eyes turning from face to face. And then they saw that beside the High Priest was standing another bearded, priestly figure, the Chaldean. It was he who spoke first.

“It is the sign! It is the sign for which I have been waiting. Lord of Gebal, men of Gebal, the day of destruction is here. Flee from your city! Flee to the mountains! Flee, O Giblites, you have but a little time to save yourselves from destruction fiercer than the arms of your enemies!”

The King turned, glaring at the intruder.

“This is the Chaldean sage I spoke of, Sire,” said Nun hurriedly.

But he was vehemently interrupted by the High Priest. “Is it not enough that the earth is shaken and the sea flies from the coast?” cried the High Priest. “Must we also suffer false prophets and imposters in our hour of peril?”

Once again, the Chaldean spoke in a level but urgent voice. “I foretold doom to the Cretans. They put me in prison for my pains and I vowed not to speak again. But, King of Gebal, I must speak now for the hour is already upon you. Your one hope is to abandon your city—”

“And leave it to our enemies from the North and West?” hissed the High Priest. “Who paid you to speak thus?”

The Chaldean spoke back calmly. “What means the destruction of your people and your city to me, High Priest? For myself, I have little fear of death, but I feel no need to seek it within your walls. Those who will take to the mountains with me, let them come. To those who choose to stay, I say farewell, for I shall not see them again.” And he bowed to the King and walked from the chamber.

When all men are in doubt, they will listen to one who seems sure of what he is saying. And for Nun it was the behavior of his element, the sea, and the sickening sight of the ships in the harbor abandoned in the mud that decided him. Besides, he had faith in the sage with whom he had shared such strange experiences. “Zayin,” he cried, “I go to summon our family and take them to the mountain, and all who can may follow me.” He ran from the room, and to the crowd of amazed palace servants and courtiers who were milling around the courtyard he cried out in the words of the Chaldean, “To the mountain! To the mountain! Abandon the city! Abandon the city!”

Remembering just in time that Beth was to be found not at home but at the Temple, he ran to the quarters of the Temple maidens. Ignoring the shrieks of “Sacrilege!” at his irruption, which seemed to cause as much panic as the earthquake itself, he found Beth, took her hand, and pulled her after him. They hurried back together through the courtyard. As they did so another terrible shock rocked the ground and the tall obelisk with the inscription to Abishram toppled from its plinth and broke on the stones of the yard. They ran from the palace gates and down the narrow streets to their home, calling all the time to their amazed neighbors “To the mountain! To the mountain! There’s no safety here!”

Standing before the house, bewildered, they found Resh and their aunt and the other women. Nun looked at Beth. She was pale and out of breath, but she seemed to be more in command of her senses than the rest of the family. “Beth,” he said urgently, “see that they pack a few necessities—just food and some wraps, nothing else—and lead them out of the back way toward the mountain. Can I trust you to do that?” Beth nodded, and giving her hand a squeeze he rushed off to the harbor. It was his duty at least to warn the crews of the ships. As he ran along the quays he saw that the water was now returning, not wave by wave as when the tide turns on ocean shores, but welling up over the rocks and pouring back through the harbor mouth in a great surge. He found his own crew, and others standing in consternation at the sight. “Abandon everything!” he commanded. “Save yourselves! There is nothing we can do here.”

“The sea’s returning, Master.” It was his boatswain who spoke. “Can’t we put to sea—I’d trust it more than this shivering soil!”

For a moment Nun felt the man might be right; but he had lost his usual faith in the sea. “Look after your families, men,” he cried. “Take them to the mountain. Those are your orders. Save the people of Gebal! The rest must look after itself.” And as they ran from the harbor they saw to their horror that the water was not stopping at the high-water mark, but was gradually and with a deadly calm lapping the quays and swamping the warehouses.

As Nun passed through the poor quarter round the docks, yet another fierce shock made him stagger in the street and brought many of the roofs of the houses tumbling down. Everyone was now out of their houses, and he did his best to calm the panic and direct them, by families, to the mountain. Farther on he heard another voice raised above the wails and shrieks of the bewildered citizens, repeating the same message: “To the mountain! To the mountain!” To his amazement it was the Chaldean, standing prophet-like on a flight of steps, urging the population to seek safety.

Nun made his way through the throng to the Chaldean. “Come, sir,” he cried. “Surely you have done enough for the people of Gebal. Save yourself! Follow your own good advice! Let me accompany you to the mountain.”

The streets were so crowded that Nun decided it would be quicker through the open spaces of the palace and the Temple courtyards. The guards had long since abandoned their posts at the palace gates and no one stopped them, but standing in the middle of the great court, by the side of the sacred pool, from which the water now flowed was a solitary figure. The High Priest!

“Will you not save yourself now, Your Reverence?” Nun called as he tried to intercept their flight. The High Priest said nothing as he planted himself squarely before them, his eyes flaming with fury.

“This is no place to stay, Your Reverence,” said Nun. He cared little whether the High Priest saved himself or not, but he could not ignore him.

“This place,” hissed the High Priest, “is the holy place of El, of Reshef, and of Balaat-Gebal. Though all the city, the King included, may choose to abandon it at the word of a traitor, for me it is a place to stay. When all is done, this is but an earthquake. I have known them before during the many years the gods have permitted me to live. Three shocks, and it’s over, and the work of rebuilding must begin. But this time our enemies will be in possession, because you, Son of Resh; have listened to one who was sent from the East to betray us. May they pay you well for it, Chaldean!” And the High Priest turned his back.

For a terrible moment Nun doubted, and wondered if the High Priest might not be right. He looked at the face of the Chaldean beside him, but in it he saw the last thing that he expected. He saw compassion, and when the sage spoke there was sorrow in his voice. “Farewell again, High Priest of Gebal,” were the Chaldean’s words. “Pray to your gods that you may be right. But I fear we shall not meet again.”

Together Nun and the Chaldean made for the land gate of the town, and then up the track among the olive orchards and terraces. As the track became steeper he began to realize what an old man his companion was. He moved slowly and painfully, and Nun, who was no mountaineer himself, had often to help him. But whenever they met families who had settled themselves on the lower slopes, the Chaldean urged them to go higher, higher. Where the pine woods began, they came upon Resh and the aunts resting at the base of a great rock, while Beth stood anxiously looking out from the top of it. Nun was relieved to see them, but the old man cried urgently, “Bid them climb higher, bid them seek the tops of the foothills, the level spaces! There is no trust in the rocks and cliffs now.”

Nun began to protest. “Surely this rock has stood for ages above Gebal! What can be safer?”

But the sage said, “Indeed, that rock may have stood for ages, but when the hour of destruction comes, who knows what rock will stand?”

So Nun urged his family and the other Giblites upward to the rounded tops of the foothills and the flat lands before the mountains themselves began. He settled Resh and the older women on a gentle slope that gave a view of the city below and the sea coast to the North and South, and told Beth that he was going to search for Zayin, and the King.

As he scrambled across the face of the hill toward the South, his heart stood still as he saw a line of hundreds of figures winding across the other side of a valley, with the sun glinting on their armor and weapons. An army! Then he realized it must be Zayin’s army coming up from the direction of the Dog River. And yes, at the head of them was a figure mounted on a horse. Zayin must have ridden down the coast and diverted the army up into the hills.

Nun went ahead to meet his brother, meaning to advise him as to the safest places on the hills. In the glaring heat of the afternoon, the population of Gebal was sorting itself out, family by family, over the bare hillside. Mothers were still anxiously asking after children they had mislaid in the exodus from the city, crying children were being led from group to group, looking for their parents. Old people were being settled comfortably on the ground, babies were being fed, women were already wandering in search of water, young boys were running and climbing over the rocks, carried away by the excitement of the moment and pursued by the angry cries of their parents. But those families that were already quietly settled, and lonely individuals who had nothing to do but sit and wait, eyed Nun as he passed among them and asked, “What next, Son of Resh? What is going to happen?” But Nun himself had not yet had time to consider the question.

Zayin was already disposing his troops when Nun came up to him; but on Nun’s advice he ordered them to move on up to the level ground, and to make his headquarters with the remainder of the family from where there was a view of all the terrain below. And on their way back they saw, among the latecomers from the city, another party of armed men, accompanied by some gray heads, and carrying a litter.

“Palace guards!” exclaimed Zayin. “It must be the King himself.” And meeting him they directed the litter bearers to the hilltop where the King was ensconced on a throne-shaped rock.

Then a silence seemed to fall over the hills, on which the entire population of the city of Gebal were spread in the hot, still afternoon. The persistent voices of the grasshoppers, crickets, and cicadas seemed to be asking, over and over, “What next? What next?”

Beth, sitting between her brothers, looked anxiously at Nun, and murmured, “There have been no more shocks since the three we felt in the town.” Her voice sounded a question that must have been in many minds. Had all this alarm been over a few minor tremors? Who was going to be first to admit a false alarm? They looked at the Chaldean, but he seemed to be watching the western horizon with such intensity that there was no room for doubt in his face.

Then a mutter seemed to run through the crowd on the northern side of the hill, and people began to crane their necks and point excitedly up the coast. Zayin and Nun stood up to look in that direction. Round the foot of the farthest headland to the North they could just make out a black line, but what really caught the attention were intermittent flashes of reflected sunlight.

“Armor,” said Zayin briefly. “The enemy from the North.”

“What are we going to do?” asked Nun, aghast.

Zayin merely looked at him. At the very same moment a breathless soldier came running up from the direction of the southern wing of the army. “General Zayin,” he gasped. “They come! They come!”

“I have seen the army of the North,” said Zayin curtly.

“No, my lord, the Egyptians! They are advancing from the Dog River. You may see them from that hill.”

The messenger looked at the General, as if expecting an order. Zayin looked at Nun. They both looked at the Chaldean, who still seemed to be standing in a trance, his eyes fixed on the West.

“We are to stand, here, like spectators at a ritual, and see our city occupied?” asked Zayin with a set face. There was no one who could reply “The participants are not yet ready for the ritual,” said Nun, his eyes, too, on the western sea. “We await the Cretan fleet.” With his hand he shaded the sun from his eyes. Were they deceiving him, was he imagining what he expected to see, or were there tiny grains scattered over the taut blue silk of the sea, moving imperceptibly from the hazy horizon toward the shore?

As they stood there, frozen immobile in the hot afternoon, it was Beth who broke the spell. Leaping to her feet she cried, “Zayin, Nun! you can’t stand there and do nothing!” And the two brothers were both on the point of giving way to the same impulse to hurl themselves down the mountainside, had not there come at that moment a great cry from the Chaldean sage. He was standing erect with both arms outstretched toward the western sky.

“BEHOLD! IT HAS BEGUN!”

The sun stood halfway down the sky, in the dead middle of the afternoon. But out of the horizon haze, a little north of west, there was climbing a dense black cloud in the form of a towering Giant. With monstrous speed it reached the height of the sun, solid black from base to head, then continued to spread as quickly across the sky to north and south, until the sun itself was glaring through a reddish-yellow mist, and then was blotted out completely by a blanket of intense black. Now all the western sky was black, and the sea was black beneath it. As the hot rays of the sun were cut off, a deathly chill seemed to fall over the mountainside, and a great wail of terror arose from the Giblite multitude as they flung themselves to the ground and cowered before the awful spectacle.

Then came the earth shock, compared with which the previous tremors had been the slightest twitches of a sleeping Giant. Prostrate against the solid rock, the Giblites felt repeated blows shaking the roots of the mountain, as if monstrous limbs were striking upward through the earth’s crust, hacking their way through. All minds were numbed, but what was left of Nun’s recalled the western isle and the Giants that were said to be imprisoned beneath it. Indeed, the very mountain chain seemed to be breaking up: cliff faces and escarpments were wrenched loose, and great crags rolled over and over into the valleys or into the sea, and the Giblites who had been unwise enough to settle on hanging rocks or shelter beneath them were carried down to their death or crushed in their headlong course.

After the cloud, and the shock waves, came the sound, and this was like all the thunderstorms a man might hear in his lifetime, rolled together in one incredible moment.

Below, the face of the sea was almost indistinguishable in the darkness, but if anyone had eyes left to see and mind to register, there was still enough light from the eastern sky to see the next messenger from the cataclysm in the west. At first a line of white foam detaching itself from the black horizon, it revealed itself as a gigantic wave rushing with unbelievable speed toward the coast. It seemed to break, to those whose horrified eyes took in the sight, not against the rocks of the shore but against the very slopes of the mountain range, so that the watchers had a mad fear that it would climb and wash them from the hilltops where they lay. The city of Gebal was lost in a smother of darkness and foam, like a child’s sand castles swept by the advancing tide.

Then the wind reached them. The Giblites pressed themselves against the rocks, fearing to be lifted and hurled into nothingness by its force, which was indeed the fate of many who were on exposed crags and peaks. In the pine belt, the trees lay down once before the blast, and did not rise again; they had been uprooted or snapped off short in their thousands. The wind continued unabated, and spread the black cloud across the sky even to the farthest East. And after that all sense of time was lost; no one could tell when the darkness of day passed to the darkness of night, no one indeed could ever say whether it was for only one night, or two, or many, that the survivors of Gebal clung helpless to the mountainside while chaos returned to the waters and the firmament, and all light was extinguished save a ghastly red glow from the West that had nothing to do with the sun.

Beth opened her eyes. She saw a gray world—gray skies, a gray sea, gray ashes falling from the sky and covering the rocks. There were other forms around her, stirring from what might be sleep.

She tried her tongue: “We are alive!” she said doubtfully.

“Are we?” came a voice. It sounded like one of her brothers.

“Impossible!” said another voice. It sounded like her father’s.

She rubbed the sleep and the ashes from her eyes.

“Father! Nun! Zayin!” she said. Three other forms sat up, and a fourth, which she recognized as the Chaldean’s.

“We have been sleeping,” said Beth. “Wake up! We are alive.”

“How can you be sure?” asked Resh, his voice also full of doubt.

“I am here. You are here. Nun and Zayin, we are here, aren’t we?” Beth said.

Resh tried to collect his wits. “But what use is there in being alive, when the world has come to an end?”

A great sadness came over Beth. “Has the world ended, Father?” she asked.

“Surely it did,” Resh said. “Is not this the afterworld, where spirits eat mud and ashes?”

Beth recognized that part of her sadness was only hunger. “Eat, did you say, Father? Are you hungry? I am, but we brought food from—” She did not want to say, “From the world.” “We brought food. Here!” she rummaged in a bundle lying near. “Cheese, and olives. And bread—see, it is quite fresh, as if it was baked yesterday. Yesterday! Is that possible?”

“Certainly it was in another world that it was baked,” said Resh. “But let us eat. Zayin? Nun? It is well we took food with us to the afterworld. We need not eat earth yet.”

Zayin accepted the food, but he was standing up and looking around him as he ate.

“What is this talk of the afterworld?” he said at last. “It seems to me that this is the side of the mountain above Gebal where we came before—” He could not finish the sentence. “Look, here are the people of Gebal around us. There are my soldiers. Wherever we are, we are not alone.”

They realized that other families were stirring round them; people were talking in low voices, babies were crying, children were calling for food and water.

“All souls that ever lived meet in the afterworld,” muttered Resh. “We cannot expect to be alone.”

“My body feels as it did,” Zayin said musingly. “I feel—I feel that this body should ache with pain, with the blows it has suffered. But I feel well. More bread, if you have it, please, Beth! I am certainly thirsty. We must find water.”

Then Nun spoke. “Zayin, Zayin, what of the armies, the invaders? And what of the city?”

Zayin struck his head. “Ah! If the world has not ended, what is happening there? Our city!” He strode to the edge of the slope and looked down. They waited in suspense until he returned the short distance.

“Well?” asked Nun.

Zayin’s voice in reply sounded distant, baffled. “I can make nothing of this gray world and gray sea. And the ashes!”

“The city, man, the city!” repeated Nun. “Is it still there?”

“Yes,” replied Zayin, sitting down and taking another mouthful. “It is still there. But it seems—dead.”

“The world is dead,” said Resh. “It came to an end.”

“I think I am alive,” said Nun. “I know this bread, cheese, and olives are delicious. Have we survived—survived whatever it was that happened, and are we to go on living in a dead world? Chaldean, eat, pray! Prove that you, too, are alive. But tell us. Tell us what happened!”

Just then a Giblite came over from another group, carrying a waterskin. “We have water to spare, Resh and sons of Resh. Drink, I pray you. And tell us what we are to do, for no one knows.”

They thanked him, drank, then Nun turned again to the Chaldean. “You who foretold the future, interpret to us poor ignorant ones who cannot rightly remember the past or understand the present. Tell us what happened, then perhaps we shall know what we must do next.”

The Chaldean finished eating, drank, and began to speak slowly. “To explain the present may be harder than to foretell the future. To decide what to do is always hardest. You say I foretold what has happened. Indeed, what I read in the stars, together with a voice within me, my foreboding, predicted a great calamity. The stars suggested a time. I traveled until I felt I had found the place. Nun the Seafarer, you will remember the island north of Crete?”

“The island without water, where they entertained us with wine and told of the buried Giants?” said Nun. “Thira. Can I ever forget it?”

“That was the place,” said the Chaldean.

“Then their story of the Giants was true?” asked Nun, beginning to understand.

“Certain it is that, buried beneath the crust of earth we live on, lie forces that were free at the beginning of time and are now imprisoned, call them Giants, monsters, Titans if you wish.”

“And from this place,” said Nun, “they escaped?”

“That is what I believe must have happened,” said the sage. “If ever you voyage again to the isles of the west, do not look to be entertained again by our former hosts. My vision tells me that they were burned, by the first great outbreak of heat, into the ashes which are now falling over the world. Do not even look for the mountain of Thira. It, too, was consumed in an instant, and you will not see it again.”

The listeners were silent for a while, trying to comprehend the disintegration of a mountain. Then Nun spoke.

“The sign, Chaldean, what of that? The waters receded from the shore before our eyes, and you said that was the sign for the destruction to begin. Where did the waters go?”

“Who can say?” replied the Chaldean. “But we know when the earth quakes, great chasms may appear in the land. May not this happen under the sea? May not the waters of the sea pour down such gulfs until they encounter the unquenchable fire of the underworld? Then, when one inexhaustible element meets another—what struggles must follow, what release of inconceivable forces?”

“Speak to us of Giants,” said Zayin. “I cannot understand your philosophy of elements and forces. But a Giant we saw, a Giant in the form of a cloud, rising in the west. I can believe that the Giants have escaped and conquered the world. Tell us, Chaldean, are all the kingdoms of the earth destroyed?”

The sage’s eyes took on a distant look as if he were trying to see beyond the gray horizon. “For great Knossos, court of proud Minos, the destruction I foretold must have come to pass—yet Knossos, among its mountains, may rise again. Mallia and the cities of the Cretan coast have been overwhelmed, and for all its great wealth Crete cannot remain a power among nations for long. We all beheld the great waves that sped across the sea from the central eruption, like ripples from a stone cast into a pool. Wherever these reached the shore, the dwellers on the coast must have been swept away—”

“The armies!” cried Zayin. “Our enemies that were marching from north and south to attack us! They must have been carried away like ants in a torrent!”

“The Cretan navies too,” said Nun. “They are certainly destroyed. No ships could have lived in that sea.” He paused, and then added, “Our ships in harbor too. What can be left of them? And our city? Before we rejoice over our enemies, Zayin, let us know what is left for us to rejoice over. Chaldean, you say that even Knossos may rise again. This is not the end of all things, then?”

“The end of all things? No,” replied the Chaldean. “In my country and in Upper Egypt it may be that they have only looked upon this darkness and wondered. By the same token, I must soon return to my own people and relate these disasters.”

“But what of our future?” said Nun. “Will you not prophesy for us? Is the nation of Gebal to rise again, or are we to die here on this ravaged mountainside? What do the heavens hold in store for us?”

“How can I read the secrets of the heavens, when night and day they are still wrapped in the clouds of this catastrophe?” asked the sage. Then he rose to his feet and looked at the group of Giblites that had gathered around him, and went on. “Nevertheless, I shall speak of your future—what any child among you could speak. People of Gebal, if you sit here on this mountainside and do nothing, you will surely die. If you descend to your city, to your farms, and your shipyards, you will find your buildings overthrown, your crops and orchards devastated, your ships smashed to pieces. You may wish then that you had been wiped out on the first day of this calamity. You may feel that you might as well have stayed to starve on the mountain. But mankind is not so easily released from its penance, its commitment to toiling, striving, building. You may have to start from your beginnings again, fashioning your simplest tools from what you have to hand, like the most primitive tribes. Yet, one advantage you do have over primitive peoples. Your material possessions may be lost, your written records destroyed, but each of you carries in his mind the patterns of your civilization. And you may learn from this disaster that what you carry in your minds is of far greater value than your material possessions. General Zayin, you have only a remnant of your armies, your military stores may be destroyed, your sources of armaments cut off—yet who knows, the future may see the armies of your nation crossing deserts and mountains in lands you have not yet heard of, if its leaders retain the spark of military imagination I discern in you, though the gods know I am no man of war. Nun, Captain of Ships, I fear you have no ships now to command, and your very harbor and shipyards may be unusable. But a few generations to come may see ships from this coast penetrating to unknown shores and islands, to seas which at present have no name, thanks to the skills of navigation which now exist in your mind alone.”

The prophet’s gaze fell on the face of Beth, solemn and open-eyed, and he permitted himself a gentle smile. “Even your daughters, people of the coast, show signs that they may be the forebears of queens who shall become legendary in times to come for their wit and wisdom.” Beth blushed and smiled back shyly, and the Chaldean’s eyes wandered over the rest of the assembly. “Bear witness, Giblites, I read this not in the stars but in your minds and faces. And, indeed, there may be one among you, whose face I do not know, and who carries in his mind a secret of even greater worth, a secret seed that, planted here and now, may grow and spread over the face of the earth, beyond the farthest marches of your armies or the longest voyages of your ships. And this seed may be something which seems at present no more important than a childish game—”

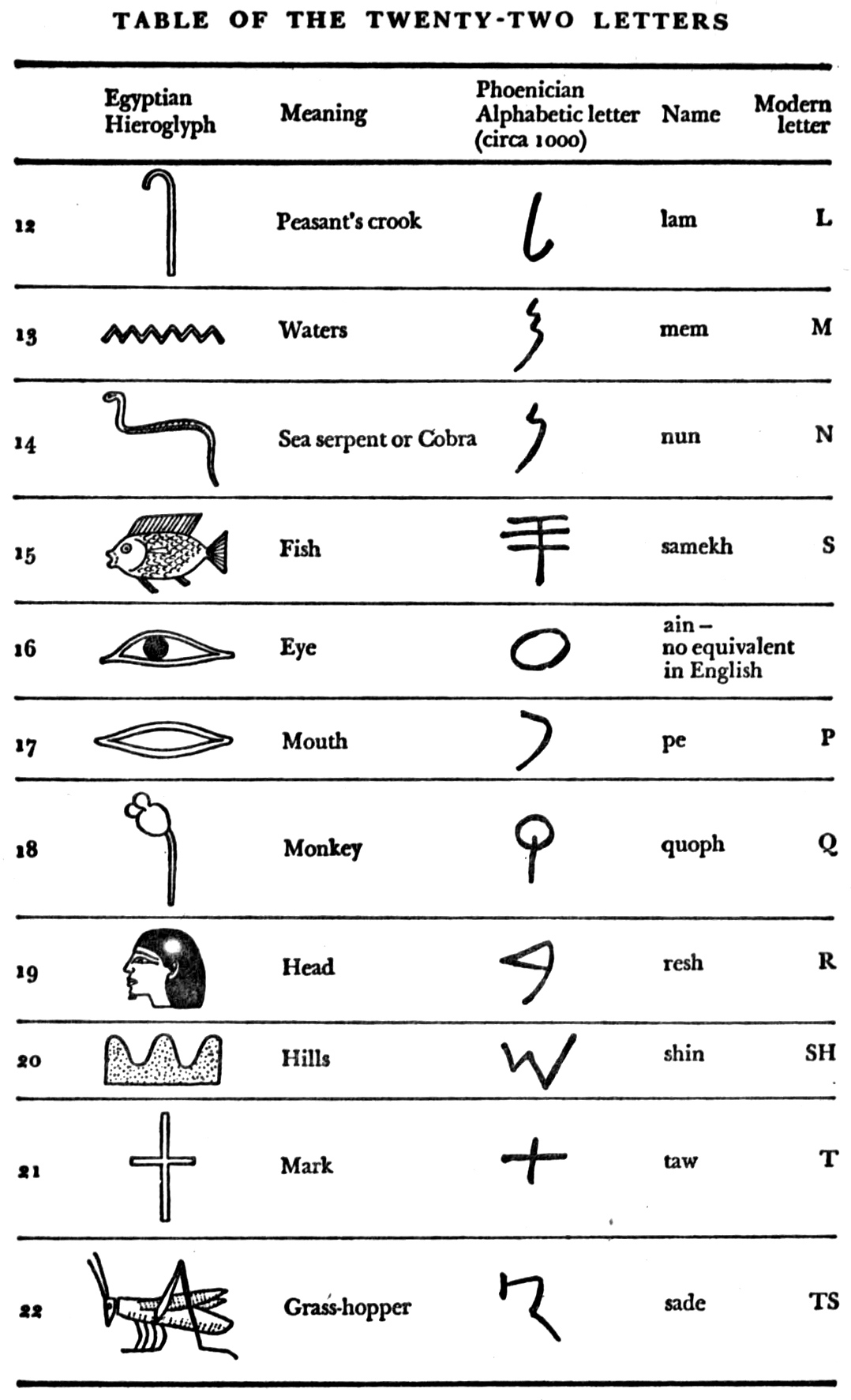

And, unaware that she was doing so, Beth spoke aloud. “Like the twenty-two letters! I wonder where Aleph is.”

A traveler was descending the slopes of the mountain above Gebal. He had passed through the belt of the cedar forest, and had observed with wonder and dismay the tangle of uprooted trunks and splintered limbs. Only the smallest seedlings and most pliant saplings were still growing, with a few ancient trees of great girth and low growth in sheltered places. He lingered for a time in a clearing where trees had been felled some time ago by the hands of men and still lay waiting to be carried away; then he continued on down a track until he came to a place of bare rocks. Here there were great wounds in the side of the mountain, where crags had been torn away and left raw, red unweathered rock behind. He came to the pines. Every one of them lay flat against the ground, their tops pointing away from the West. The traveler closed his eyes: he was faint from hunger, and his head swam in the hot sun. He listened to the sounds of the pine wood: the cicadas sang their senseless song, just as he remembered it, among the withering branches, but he missed the music of the wind that used to play in the swaying pine-tops.

The traveler’s heart was full of dread and his body was very weary after much solitary journeying and great privation, but he forced himself on toward the city. He came to a point where he knew he would be able to look down on Gebal, but he was afraid of what he might see, or fail to see. He reached the edge of the rocks and looked down. Hundreds of feet below in the sun’s glare, the promontory of Gebal could be clearly seen. To the right, the blue indentation of the harbor was as it used to be. The traveler screwed up his eyes and blinked, trying to interpret what he saw; the outlines of the city wall, the palace, the temples, and the houses seemed to be just as he remembered them. His heart lifted with relief—and then he began to distinguish what was lacking from the remembered picture. The neat nutshell hulls of boats were missing from the harbor. The rectangle of the palace was not sharp and bold as it had been. It was perhaps only the empty husk of a building. And, try as he might, he could not make out any sign of life. He tried to convince himself that he was still too high to distinguish human figures. He did not wish to think he was looking down on a deserted city.

He felt he must keep going, or he would collapse from weariness. He came to the olive orchards. They, too, were bare, splintered, stripped of their leaves and fruit, though the gnarled black trunks and roots still seemed to clutch the rocky soil. As he reached the lower terraces, the walls of which were all scattered and crumbled, he thought his exhaustion was playing tricks with his senses. It was still half an hour’s walk to the harbor or the shore—yet there was a ship, wrecked in a tangle of olive trunks, its anchor cable trailing out behind it through a plantation where the stumps of fig trees were swathed in rotting seaweed.

The sun was setting now beyond the city. Every sunset since the time of the darkness had colored the whole sky with flaring hues of red, orange, and violet, and so it was this evening. But the traveler did not stop to admire them. He must reach the city before dark. If he could encounter seagoing ships in an olive orchard in broad daylight, he was afraid to think what he might see in the city after nightfall. A people of ghosts?

Picking his way in the gathering dusk over pebbles, sea sand, and rotting weed he approached the city walls. They still stood high and black against the sky, but their tops were jagged and crumbled like the walls of a ruin. At the landward gate, two soldiers barred his way. They were gaunt and famine-stricken, living specters—but they were living.

“Who goes there?” came the challenge. “We admit no strangers to Gebal. We’ve scarce enough to keep ourselves alive.”

“I have come a long way,” said the traveler. “I am fainting with hunger.”

“There’s no food here,” said the second soldier. “Be on your way, stranger!”

“But I am a Giblite,” persisted the traveler.

“A Giblite?” repeated the first soldier, coming close to the traveler to scan his face in the dusk. “I don’t recognize you. What’s your trade?”

“I am a scribe,” said the traveler. “Apprentice scribe,” he corrected himself.

“Gebal has no scribes,” said the second soldier curtly. “They all stayed with the High Priest and got drowned. I shouldn’t linger here, stranger! You might get skinned and eaten. There’s famine here.”

The traveler leaned weakly against the stone of the great gate. “Who is left alive here?” he asked. “My father was Chief Mason, my brothers were General Zayin and Nun, the sailor.”

The second soldier came near and examined the traveler’s face in the thickening light. “Lucky you got here before dark! We’ve no oil for lamps here, and we’d have made short work of you. I remember you, though. You’re old Resh’s son, aren’t you. Used to be tally clerk at the Temple. What’s the name? Aleph, isn’t it?”

Aleph nodded. “Are they alive, my family?”

“I reckon you’ll find them in the same place where you used to live,” said the soldier. “Mostly we’re living in the ruins of the old houses and digging around for what we can find. Come on in. Another mouth to feed, but I dare say they’ll be glad to see you.”

Wearily, but with lightened heart, Aleph made his way through the rubble-filled, barely recognizable streets. On every side families were settling themselves for the night in makeshift tents or lean-to shacks propped against whatever walls were left standing. Some were sharing out meager rations of food, but everyone seemed subdued with the quietness of hunger and exhaustion. He even passed neighbors who smiled and saluted him wanly, unaware that he was returning from a long absence. He did not stop to tell his story.

He came to the northern slope of the mound on which the city stood, where he estimated that their house used to stand. But he could distinguish no landmark. He stood uncertainly, listening to murmured conversations of the citizens around him. Then as he stood he realized that his ear had become attuned to two, three, four voices that he knew. The voices of his family, raised in familiar argumentative tones.

“Men cannot work without food.” It was the voice of his sister Beth.

“Send the army on foraging expeditions.” It was Zayin. “Let them bring back food from neighboring states.”

“Keep the army here to clear the city and rebuild. Let us build ships too. Then we can trade and bring food,” came the voice of Nun.

“We can build neither ships nor houses without timber. We must fell timber and bring it from the forests,” said the voice of his father, Resh.

Beth was about to bring the argument in full circle by saying “Woodcutters cannot work without food—” when Aleph interrupted in the darkness.

“There are twenty-nine felled trunks on the edge of the forest,” he said clearly. There was a dead silence. “I counted the trees, Father,” he added.

His family emerged from the shack in which they were sitting and surrounded him. Beth and his father were both trying to hang round his neck, Nun was shaking him by the hand, and Zayin was thumping him on the back. It was all too much. He would have fallen to the ground in a faint if they had not all held him up and carried him in to what was left of their home.

When he came to himself, he could just see their faces by the light of a little wood fire. Beth spoke: “We found an unbroken jar of wine and some parched corn in the rubble of the house. We were saving it, but you must eat, Aleph dear, you are not well.”

“We had given up hope for you, my son,” said Resh. “Where have you been?”

“I was in Sinai, in Pharaoh’s mines—”

“Yes, yes, we know, we know,” said Beth soothingly. “We got your message.”

“My message?” said Aleph in bewilderment. “You mean the bird …? It came back, and you understood?”

Zayin spoke as though something had just struck him. “If that bird had not told us about Pharaoh’s army, the Egyptians would have captured the city—”

“Before the destruction came,” put in Nun. “And they would not have let us take to the mountains and—”

“And we would not be here now,” finished Beth quietly.

“Tell me what happened,” said Aleph. “They sent me from Sinai, northward with a supply column. There was darkness and confusion, and I escaped—”

“We shall have plenty of time to tell our stories,” said Beth. “Now you must eat.”

Aleph took the wine and the water-gruel. “I am sorry to be just another mouth to feed,” he said.

“Nonsense, my boy,” said his father. Resh turned to the others, “Aleph is now the only scribe in Gebal.”

His father spoke, proudly, but Aleph felt all his shame returning. He turned his head away. “You know I never learned all the six hundred and four signs, Father. Now there is no one to teach me. I am no use to anyone.”

“Aleph,” Beth said. “You have your twenty-two letters. They seem to be enough. One day all our story will be written with them.”