CHAPTER 4

Choosing to Do the Right Thing for Your Real Team

What’s the Problem?

Getting those around you aligned is more difficult today in part because of the rapid rate of change. Think internet speed. But it’s way more than that. Life is so much more complex. Consider all the new positions and roles in companies today. In a biotechnology company I’ve worked with, it’s really hard to keep up with all the new functions. At home, parents have to worry about cyberbullying. That’s a relatively new concept. Who knows what’s next?

In business settings, most people think that once you’ve established a strategic plan with annual goals, that must reflect a healthy degree of alignment. That’s like thinking that once a couple has said their vows, it truly will be happily ever after. It is much more than people agreeing on priorities, goals, or even promises.

We can split this into two different problem sets at work. One is getting a top team committed to a high-level direction and more explicit goals. Having facilitated hundreds of off-sites with executives and their management teams attempting to do this, I have some insight into the challenges.

If you’re one of those in upper management tasked with the responsibility of defining direction for or with your team, I’m sure you’ve experienced this: Toward the end of the meeting, you ask each person on the team if he or she supports the final strategy and goals. All concur. But what can you anticipate immediately following your team meeting? At least one person will come to your door (or cube, or open space) and say something like “I didn’t want to say it in the meeting, but I’m concerned with our conclusions. . . .” That’s when you want to scream. There really is a better way. It would have been much more constructive for that dissenting opinion to be aired within the meeting rather than after, so it could be dealt with as a team.

The major obstacle for higher-level teams is managing the discussion with a high degree of candor, following a reasonable structure for a set of meetings. It’s through the discussions, sharing, and shaping an evolving context that the team moves gradually to the same page. That will be explained further in the next chapter.

The other problem set has to do with getting everyone, including even those who contributed to developing those strategies and goals, to subsequently work throughout the year (or quarter) making daily decisions about what to do and not to do. If we didn’t have functions, departments, agencies, and disciplines with markedly different priorities and missions, that wouldn’t be such a grave concern. But the reality is almost everything these days is cross-functional/departmental/agency, etc. Some organizations refer to this as matrix management, but you get the idea.

Some consultants will tell you to simply deliver on what you’re being measured against and say no to all outside requests. That would work if we weren’t interconnected. But if it is a reasonable request from another group you work closely with, should you trust your judgment and try to do what’s right? If you don’t and you become known as the person who always says no, what’s the likelihood that others will help you in return when you ask?

To make it more real, what if your own manager or team leader doesn’t seem to want you to help other groups? Like many managers, they may be too myopically focused on their own world, refusing to acknowledge the bigger picture and what’s best for the larger organization. But you may sense that not helping out could obstruct an even more important, broader goal. In health care, that goal could be patient safety. In business settings it could be quality, time to market, improving a critical process, or building market share. In government it could be everyone’s safety.

What happens at home when you give in to your partner just to end an uncomfortable conversation, but you don’t get to a real commitment? You’ve been there—or you’ve been at the other end, not giving in until you hear what you want, a weak but stated agreement. How long does the agreement last before it cracks? People can usually tell when they have a real commitment from others. The body language, the eye contact (even in a virtual meeting)—all converge to suggest a deeper alignment. It takes a concerted effort to discuss the issues candidly to build a real commitment.

Are there times when reasonable people simply can’t agree? As mentioned earlier, I’ll never forget working with a start-up executive team on their strategy. Throughout the couple of days, it became more and more apparent that there was no agreeable path forward. They ultimately split up the company, amicably, and ventured on their separate paths. But in the vast majority of situations, people can find mutual solutions with the right mindset and the skills to make it happen.

ALIGNMENT TO DO THE RIGHT THING: KEY PROBLEMS

The goal of larger organizations is to align at the most senior executive levels and then communicate and translate vision, strategies, and company goals down the organization in order to align team and individual priorities with the greater company objectives.

We know this is not a perfect world, and it can be a challenge to communicate goals, ensure that those goals are translated in terms of what they mean to each team and ultimately each individual, and then communicate any adjustments throughout the year. Not only is it challenging to align down the organization, but we also see misalignment or duplication of goals across functions and teams.

This challenge can be magnified when the executive team has stalled in their decision making or, in some cases, doesn’t want to communicate strategies more broadly for fear that the company’s competitive advantage could be put at risk.

While the framework and tools in this book can provide perspectives to align the most senior teams, our focus is on what the individual, at any level of management or as a professional, can do to navigate within his or her organization—to do the right thing. By “professional,” I am referring to anyone who has a degree of discretion to make choices about how to spend his or her time, what to focus on, whom to respond to, and what priorities actually get completed. In a typical technology company, the professionals and management can make up about 90 percent of the employees.

The top three problems with this second mindset, alignment, include:

-

Lack of alignment predictably leads to diluted efforts and suboptimal results, especially given the need for cross-functional collaboration.

-

People will primarily identify with their immediate team to whom they report—kind of like people do in families, tribes, and other groups to which they belong. The broader team, arguably the more important team in most organizations, feels secondary.

As an example, a marketing professional in one business unit may identify primarily with the other marketing people in that business unit. Second perhaps is the business unit—or perhaps the global marketing team. And third typically is the company. The most successful team leaders and team members have the capacity to think in terms of what’s best for the variety of teams along with the company—all of which combine as their real team—rather than maintaining a more limited view of what’s best for their own slice of the organization.

-

Smart people can think of more compelling things to do than they actually can do. Take a moment to consider the implications. Although some people carefully whittle down their objectives and only commit to those they can confidently deliver, many commit to a broader to-do list, not ever expecting to accomplish all the objectives. Or the team leader adds newer priorities without indicating which existing priorities can be deleted or modified.

What’s the impact of missing “only” two out of ten priorities for that month? It may not matter, but it may matter a lot. What if one of those dropped priorities was a key requirement for someone else on a related team, which then forced them to miss their goal? And what if that goal was actually much more important to the broader organization?

The Chaos Maker: Weak on Alignment

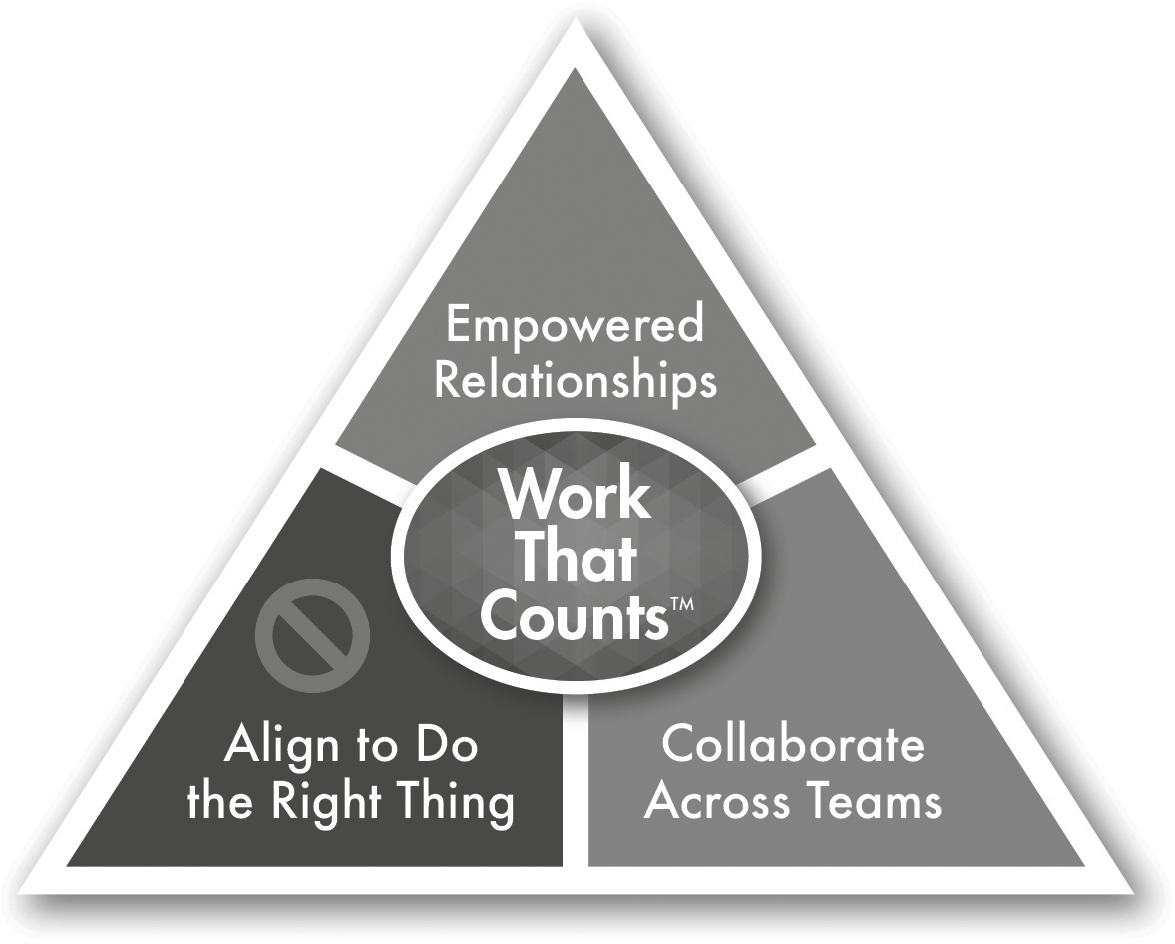

What happens if a person is strong on both empowered relationships and collaboration, but weak on alignment? They are fully empowered by their manager to take action and drive decisions, and they have the ability to influence and work with others around them, but they either aren’t aligned to the greater goals or haven’t aligned actions with the right people. This creates the Chaos Maker.

With this power to take action and drive decisions, and the people skills to partner with others, Chaos Makers can exert significant influence. But it will likely produce diluted results, and possibly the wrong or even disastrous results. At a minimum Chaos Makers could be duplicating effort with other teams in the quest to drive action. If they distract people from the more important priorities and persuade others toward decisions that don’t take into account the bigger picture, it can cause a lot of inadvertent damage.

Example of the Chaos Maker

Again, there are varying types of Chaos Makers. In general, these folks are highly regarded and trusted by their managers. People in the organization like them and want to work with them because often they have great ideas and energy. Here is an example of how it can go wrong when someone is empowered and collaborative, but not aligned to do the right thing.

Max was a leader in one of our international divisions. He was highly regarded as a savvy business leader, great with customers, and able to get things done. He had scaled his team and brought high-caliber talent into the organization. His decision-making approach and ability to deliver results earned his manager’s trust and empowerment. People in the region looked to him for direction. Max was regarded as someone who was challenging to work with, but everyone respected him because he could push people and teams to greater performance.

In his second year as division head, Max became myopically focused on his own business. He often missed the global team meetings, and given that he had a good relationship with his manager, they often skipped their check-ins. It was during this disconnected and isolated time that he missed a strategic change in direction of the broader organization. Max and his team were continuing to do business as usual, and suddenly more and more confused and angry calls were coming into—and from—the corporate office. Customers started to back away from the company and its mayhem. Max’s lack of alignment with the broader organization strategy had turned him into the Chaos Maker.

As you reflect on how important alignment is to you at work and at home, consider the pain and frustration of people essentially working against each other who are actually on the same but broader team. When my wife and I were raising our young family, we strove to maintain a mutual respect with our kids. We had a shared vision of raising them to be independent while still wanting to be together as a family as adults—to go on vacations together, even if we don’t pay for everything.

That broader alignment helped to make so many other decisions easier. The same applies in business. If we can truly align on the more important decisions, we will be much more likely to make better decisions along the way.