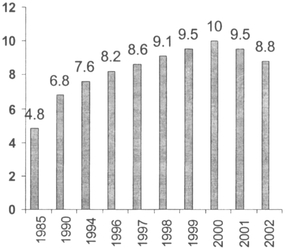

Figure 11.1 (a) Flight movements 1985-2002

Thomas Immelmann

No doubt, the current environment is a hard time for the aviation industry, when even airports - such as Cologne or Stuttgart - suffer heavy operating losses and may even come close to bankruptcy. In this situation, talking about airport regulation in terms of a price or fee cap may be cherished by some airlines1 but few airport shareholders or authorities. It will be shown subsequently that at Hamburg Airport, a sophisticated price cap regulation proves to be crisis resistant. A concise planning of the processes and the ability to have an annual validation, produced price cap regulation that both proves to be stable in bad times and keeps up its originally intended regulatory function for a fair airport-airline fiscal relation.

Founded as an airfield serving more airships than the young airplane industry in those years, Hamburg Airport was founded on a sheep's meadow a couple of miles away from what was the heart of Hamburg city in the year 1911. Since then, it has grown to an airport serving almost 10 million passengers and 70 airlines in 2000, with the traffic structure of a European "classic origin & destination" airport (see Figure 11.1). In 2000, Hamburg accounted for 165,000 flight movements, of which some 152,000 were commercial. In 2001, passenger development fell back to 9.5 million passengers and 159,000 flight movements, followed by 8.85 mio passengers and roughly 150,000 flight movements in 2002. In economic terms in Hamburg this was the worst year in recent civil aviation history. Still, with a net income of €21 million and €190 million in sales revenues Hamburg Airport proves to be one the most profitable airports in Europe, though the economic development has steadily grown worse since 2001.

Figure 11.1 (a) Flight movements 1985-2002

Figure 11.1 (b) Passenger movements 1997-2002

Located now within the city limits of Hamburg, which has grown around the airfield in the past 90 years, Hamburg Airport is not only the oldest international airport still in place at its founding location, but it also has quite complex regulatory requirements due to the fact that more than half a million people live in the direct neighbourhood of the airport. Environmental and noise restriction regulations were initially applied in 1983 and have constantly tightened.2

Another feature about Hamburg airport which should be mentioned, since it has implications for airport regulation, is the management of services. A modern business approach was developed well in advance of European airport deregulation. The management of Hamburg Airport saw quite early the challenges to be faced with the deregulation of airport business, especially in the business field of ground handling. The airport has been trying to cope with these challenges, creating a number of subsidiaries to the former Airport Authority, Flughafen Hamburg GmbH. A number of strong companies specialised in certain ground handling business fields have been founded and have successfully established themselves in the market. This strategy took some pressure from the regulatory issues to be clarified before privatization, while some of the former monopolist ground-handling services have been made ready for competition.

Table 11.1 Organization of Hamburg Airport and subsidiaries 2002

| 40% | AHS Hamburg - Aviation Handling Services GmbH |

| 100 % | AIRSYS Airport Business Information Systems |

| 100 % | ANG - Airport Networks GmbH |

| 100% | CATS - Cleaning and Aircraft Technical Services GmbH |

| 100 % | CSP - Commercial Services Partner GmbH |

| 100 % | GAC - German Airport Consulting GmbH |

| 100 % | GroundSTARS - Groundstars GmbH & Co. KG |

| 100 % | SecuServe - Aviation Security and Services GmbH |

| 60% | SAEMS - Special Airport Equipment & Maintenance Services mbH |

| 51 % | STARS - Special Transport and Ramp Services GmbH & Co. KG |

Another background feature of the regulatory framework at Hamburg Airport definitely has to be mentioned: the political will to privatize or at least partially privatize public infrastrucuture. Apparently, the public shareholders of Hamburg Airport - the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (64 per cent), the Federal State of Schleswig-Holstein (10 per cent) and the Federal republic of Germany (26 per cent) were quite aware of the danger of a misuse of the airport's monopoly role by a new private owner.3 As one of the principles of the public-private partnership before the privatization process, the public shareholders and the Ministry for Economy of Hamburg, being the executive authority for all aviation issues in the federal state of Hamburg, made the decision to establish a form of price cap regulation for all airport fees regulated by German federal law (§ 43 LuftZVO).4 This included passenger handling, parking, landing and noise emission fees, but neither ground handling service fees, security/safety charges or charges for central infrastucture issues such as baggage handling etc, nor other airport revenues from other business fields (i.e. non-aviation related rents and revenues) were to be included.

The goal was, however, to prevent a private shareholder from simply cashing in on windfall profits. The price cap contract was finally signed in 2000 with a duration of five years from 2000 to the end of 2004.5 Thus, the price cap contract would be one of the "sine-qua-non" conditions to a future public-private shareholder partnership that had been established in 2000 by the acquisition of 40 percent of Hamburg Airport by the appointed private consortium Hamburg Airport Partners (HAP), owned by Hochtief Airport, an affiliate of the largest German construction company, and Aer Rianta, the worldwide successful Irish airport company.

Prior to privatization, in the negotiations between representatives of executive authorities, public shareholders, airlines and other important customers and users of Hamburg Airport, the Government of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg and the Federal Republic of Germany, the conditions of the public private contract and the price cap regulation were brought into one formula. This formula set the reference quotient as a benchmark and a method of regulation to define the future level of fees per passenger:6

where RQ is an abbreviation for reference quotient, which represents the sum of all regulated fees per passenger charged by Hamburg Airport in 1999, To define the maximum limit of regulated fees per pax and fiscal year for the following year, the price cap formula is applied. CPI stands for the consumer price index, clearing the regulation from nominal monetary effects. Z represents the minimum decrease rate on airport fees that the airport company has to accomplish - a rate of minus 2 per cent. {-scs} means - not exactly arithmetically correct - that the increase of productivity at Hamburg Airport - also the avoidance of windfall profits by sheer scale effects of rapid passenger development - had to be shared between airlines and the airport company defined by a "sliding scale model".

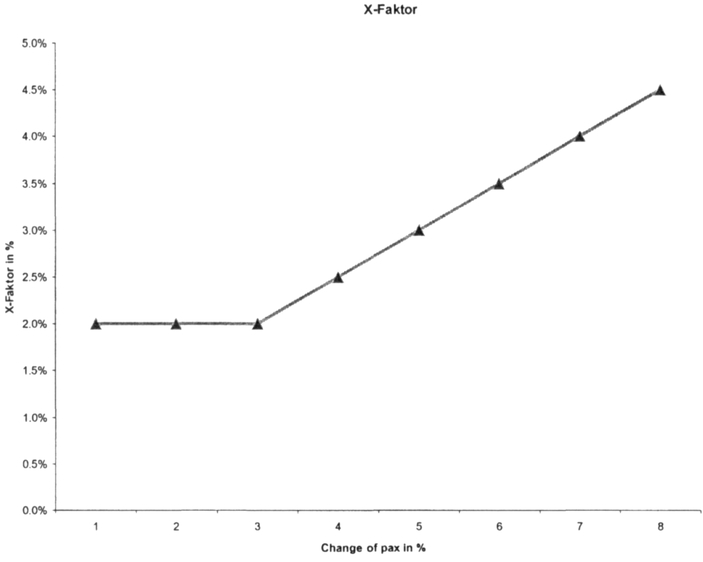

Figure 11.2 Sliding scale model

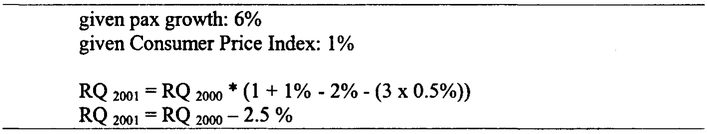

For each percentage of annual passenger growth above 3 percent - the average growth at Hamburg Airport in the 15 years before the introduction of the price cap contract - in a current year, the reference quotient of the following year has to be decreased by an additional 0.5 percent7. Fig. 11.3 gives an example of how the price cap reference quotient would be determined:

Figure 11.3 The cap reference quotient

This decrease may seem negligible at first look, but the effect of this "productivity sharing" on the market proved to be positive and underlines the marketing character of the price cap regulation - especially at an origin-destination-airport like Hamburg, where comparably small changes in the regulation framework may have huge effects on market structure.8

As shown in Figure 11.4, the effect on the development on the price cap reference quotient was relatively small, due to the fact that the second year of the price cap application at Hamburg Airport was 2001, which had a date in September to be long remembered.

Figure 11.4 Reference quotient 1999-2003 (cum.)

To understand the question why the price cap regulation had a quite limited negative impact on Hamburg Airport's economic performance, a change of paradigm has to be seen. The radical, if not revolutionary change in this price cap model of airport charges and fees for the airport company was the "head count principle", measuring all formerly regulated revenues by numbers of passengers instead of maximum-take-off-weight-tons, landing fee per aircraft type, duration of aircraft parking or other traditional ways. This was the very moment when the airport management and shareholders had to find an answers to a - at first glance simple question: what happens if passenger growth rates decline? What happens in times of crisis in aviation industry?

First, price cap protection tools in the case of a - sudden or slow - decline in the aviation market is the communication between producer and market, airport and airline, infrastructure unit and environment. None of the rules set up in the public private price cap contract are static. As described in the two annexes of the contract,9 a number of boards and control units had to be established by the airport company - not only for crisis management reasons, of course, but also for normal conditions for the surveillance of the airport's service level performance. Further, annual passenger service reports produced under demographic standards have to show the observance of high quality standards in infrastructure and service levels for passengers as well as for airlines or other business-to-business-customers. A landside customer board - a group of retailers, car rental managers and other landside concessionaires - an airside customer board - manned by airline operation representatives such as station and cargo managers - and a neighbourhood community board - have at least one session a year, with the opportunity to discuss all potential claims and critical items directly with the airport's management. In case the claims could not be answered satisfactory, the according board representatives have the right and the ability to pass on their claims to the executive regulatory authority of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg - a procedure that quite remarkably - has not happened yet. In Hamburg, this communication structure gave airlines as well as the airport the opportunity to react closely and jointly and not least - very cost-effectively on the change of security paradigms after September 11.

The most important control and steering unit is the Price Cap Review Board with executive level representatives of airlines and airline associations such as BARIG and ADL. This board meets at least once annually and is in the position to change virtually any of the price cap regulation contract paragraphs. The most important change in the price cap regulation since its inauguration in 2000 was the abandonment of the sliding scale clause immediately after September 2001, which proved to be an emergency exit - and an important one - out of the dangers of a totally passenger-figure-driven price cap at Hamburg Airport and which was decided in total accordance with the airport company. The advantage for the airport is the chance to recover faster from the sudden decrease in passenger demand in all aviation-related business fields, the advantage for airlines is the preservation of a long-term and safe scheme of airport fee decrease.

Another dimension of the immunity of the price cap contract against the general economic crisis is the real valuation/inflation index of the reference quotient. In the Hamburg case, this valuation is tied to the general consumer price index in the Federal Republic of Germany. As it seems to be one of the natural laws in the world's economy, a general economic downturn comes hand in hand with high inflation, so the real value of regulated fees safeguards the airport's infrastructure prices against rapid devaluation.

When establishing price cap regulation in an aviation infrastructure unit such as an airport, no "plan for the unplanned" may really survive its first encounter with reality. But it seems to be possible to build in emergency exits that allow partners to leave the once-defined path of regulation and comply with an abrupt change of the economic situation. To cope with the price cap's substantial decrease of airport fees by increasing productivity and cost reduction is definitely a demanding task for the airport company, but the history of regulatory performance at Hamburg Airport in the past three years has comprehensively shown that an everlasting growth in passenger figures is neither a necessity nor an absolute living condition for a price cap. And very definitely, an economic downturn or even the chance of a sudden evolving economic crisis are no argument against a price cap in principle. On the contrary, on an aggregate level, a price cap has a thorough character of providing a marketing incentive that survives in bad times and may serve as a preparation for fitness in times of declining yields and a growing uncertainty in the entire aviation industry (which has been a general trend since the late 1990s10). Or to put it more practically: an airport among the first to reasonably value its services and infrastructure in good times is the last to be visited by airline managers that desperately and dramatically seek to reduce costs in bad times - and finally reduce traffic by cutting frequencies or cancelling destinations, leaving the airport and its expensive infrastructure in even worse economic conditions.

1 Compare with i.e. Thomas C. Lawton's remarks upon the airport charges as a structural barrier against low cost airlines in: Cleared for Take-Off; Ashgate; Aldershot, 2002, p. 67f.

2 See the contributions of Hans-Martin Nieme ier and Axel Schmidt in T. Immelmann et al. (Eds), Aviation versus Environment? Papers of the 2nd Hamburg Aviation Conference. Peter Lang, Frankfurt/M. 2000

3 In fact, Hamburg Airport and the Ministry for Economy of Hamburg supported several scientific surveys on this issue before the airport privatization was underway; see W. Pfȧhler, H.-M. Niemeier et al, Airports and Air Traffic Regulation, Privatization and Competition, Peter Lang, Frankfurt/M. 1999.

4 Luftfahrtzulassungsverordnung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland

5"Öffentlich-rechtlicher Vertrag tiber die Festsetzung und Anpassung regulierter Flughafenentgelte. Abgeschlossen zwischen der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg und der Flughafen Hamburg GmbH." Hamburg, April 2000. The following is referred to as "Price cap contract". The author was the responsible spokesman for the airport in the negotiations on the price cap contract; quotes are made from the author's final draft, which was identical to the signed contract paper.

6 Price cap contract p. 4.

7Price cap contract p. 5f.

8 Compare with David W. Gillen et al, The Impact of Liberalizing International Aviation Bilaterals, Ashgate, Aldershot 2001, where the effects of liberalization of international traffic rights on a relatively small Hamburg, respectively north German market are shown.

9 Price cap contract p. 7-9 and annex 3, A, B, C.

10 Compare with Rigas Doganis, The Airline Business in the 21st Century, Routledge, London 2001, p. 9f.