Notes

The Bible is quoted in the authorized King James version, the classics in the Loeb Classical Library (Harvard University Press and (Heinemann), and Shakespeare in The Norton Facsimile [of] The First Folio, ed. Charlton Hinman (1968).

To His Sacred Majesty (Virtue’s triumphant shrine, who dost engage)

2 pilgrimage: to Dover to greet the fleet bringing Charles II back to England: ‘it being endlesse to reckon or number those that are gone, who are the flower of the Gentry of England, all striving to exceed each other in costliness of their Furniture and Equipage’ The Publick Intelligencer, 21–28 May 1660).

3 ecstatic: punning on two meanings of the word: the etymological sense of ‘out of place’, ‘Out of themselves’ (1. 4) and the lexical sense of’intensely pleasurable’ (OED) (Rochester 1984, 229).

5 one camp: the Lord General George Monck ordered the Parliamentary army, that defeated Charles II at Worcester in 1651, to march out of London on 23 May 1660 and to encamp at Blackheath, beyond Greenwich in Kent. ‘At Black Heath the Army was drawn up where His Majesty viewed them, giving out many expressions of His Gracious favor to the Army, which were received by loud shoutings and rejoycings’ (The Parliamentary Intelligencer, 28 May–4 June 1660).

7 loyal Kent: in 1648 a widespread insurrection in Kent on behalf of Charles I was savagely suppressed by Fairfax.

8 Fencing her ways: on Tuesday 29 May 1660 ‘His Majesty took his journey from Rochester betwixt four and five in the morning, the Military forces of Kent lining the wayes, and maidens strewing herbs and flowers, and the several towns hanging out white sheets’ (Mercurius Pubticus, 24–31 May 1660); moving groves: ‘2 or 300 Maids of the Town [Pursely, Kent]… marched in Rank and File, each carrying a green Beechen bough, with Drums and Trumpets, up to Stinchcomb Hill, where… they drank the Kings Health upon their Knees’ (ibid.); cf. Macbeth, V v 38: ‘MESSENGER: … may you see it comming. / I say, a moving Grove’.

10 sedentary feet: punning on two meanings of the phrase: ‘idle feet’ and ‘halting verse’ (Rochester 1984, 229).

11 youth: Rochester was thirteen on 10 April 1660; not patient: impatient, ‘Restlessly desirous, eagerly longing’ (OED).

16 father’s ashes: Henry Wilmot, 1st Earl of Rochester, died on 19 February 1658 at Ghent. He was buried first in Sluys, in the Netherlands, and was reinterred at Spelsbury, Oxfordshire.

To his Mistress(Why dost thou shade thy lovely face? Oh, why)

This is a parody of Francis Quarles, Emblemes (1635), 149–50, 170. By changing the order of the stanzas and a few words and phrases – ‘My love’ for ‘My God’ – Quarles’s passionate poem of sacred love is turned into an equally passionate poem of profane love.

19-21 ‘Stanza xi of Quarles’s Emblemes, III vii reads as follows: “If that be all, shine forth and draw thee nigher; / Let me behold, and die, for my desire / Is phoenix-like, to perish in that fire.” In Rochester, this becomes: “If that be all Shine forth and draw thou nigher. / Let me be bold and Dye for my Desire. / A Phenix likes to perish in the Fire.” There are only two verbal substitutions here of any consequence:…“behold” into “be bold”, and the most striking introduction of the word “likes” in Rochester’s versions of the third line. Otherwise, the transformation has been effected by means which are not properly linguistic: by end-stopping the second line where Quarles had permitted an enjambment and by a change in punctuation and accentual stress which suddenly throws the erotic connotations of the word “die"… into relief.… The lines are the same and not the same; another voice is speaking Quarles’s words, from another point of view’ (Righter 1968, 58).

23 flameless: the copy-text reads ‘shameless’, but the context requires Quarles’s word.

27 lamb… stray: cf. ‘it is not the will of your Father which is in heaven, that one of these little ones should perish’ (Matthew 18.14).

35 thy: the copy-text reads ‘my’, but the context requires Quarles’s word; cf. line 1.

36 die: cf. ‘the LORD …said, Thou canst not see my face: for there shall no man see me, and live’ (Exodus 33.20).

43 thy: the copy-text reads ‘my’, but the context requires Quarles’s word.

Verses put into a Lady’s Prayer-Book Fling this useless book away)

This poem is an adaptation of two poems of Malherbe.

Writ in Calista’s Prayer-Book. An Epigram of Monsieur de Malherbe

Whilst you are deaf to love, you may,

Fairest Calista, weep and pray,

And yet, alas! no mercy find;

Not but God’s merciful!, ‘tis true,

But can you think he’ll grant to you

What you deny to all mankind?

(Charles Cotton, Poems on Several Occasions (1689), 51)

Written in Clarinda’s Prayer-Book

In vain, Clarinda, Night and Day

For Mercy to the Gods you Pray:

What Arrogance on Heav’n to call

For that, which you deny to All!

(George Granville, Lord Lansdowne, Poems upon Several Occasions(1712), 124)

8 Without repentance: cf. ‘O God… Restore thou them that are penitent’ (The Book of Common Prayer (1683), sig. BIr).

16 easy steps: ‘There is no source in Malherbe for Rochester’s ideas of a sensual grains ad Parnassum… The metaphor was probably familiar to Rochester from Socrates’ speech in the Symposium but in the anti-religious context of the poem it is made to provide an ironic commentary on its Christian application, exemplified in Crashaw’s title Steps to the Temple and in Adam’s words to Raphael in Paradise Lost, Book V, “In contemplation of created things / By steps we may ascend to God” ’ (Treglown 1973,45–6).

17 joys… above: the phrase recurs in a poem of which the attribution to Rochester is confirmed (12.22).

Rhyme to Lisbon (Here’s a health to Kate, our sovereign’s mate)

‘The… E. of Roch[ester] coming in… when the K. Charles was drinking Lisbon [‘A white wine produced in the province of Estremadura in Portugal’ (OED)], They had bin trying to make a Rhime to Lisbon, Now saies the K. here’s one will do it. Rochester takes a glass, and saies A health to Kate! …’ (B.L. MS. Add. 29921, f. 3V). For these extemporaneous verses Rochester employed a common ballad stanza, A4B3A4B3, with double rhyme in the short line. It can be sung to the tune of ‘Chevy Chase’ (Simpson 1966,96).

1Kate: Catherine of Braganca.

3 Hyde: Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, was blamed for negotiating Charles’s marriage to ‘a barren Queen’ bishop: Gilbert Sheldon, Archbishop of Canterbury, married Charles and Catherine of Braganca at Portsmouth on 21 May 1662.

4 of his bone: cf. the solemnization of matrimony: ‘we are members of [the Lord’s] body, of his flesh, and of his bones. For this cause… they two shall be one flesh. This is a great mystery’ (The Book of Common Prayer (1683), sig. K 12r)

.

Song (Give me leave to rail at you)

A reply to Rochester’s verses, in Elizabeth Malet’s hand with corrections in her hand, is preserved in Nottingham MS. Portland Pw V 31, f. I2r:

Song

Nothing adds to love’s fond fire

More than scorn and cold disdain.

I to cherish your desire

Kindness used, but ‘twas in vain.

5 You insulted on your slave;

To be mine you soon refused.

Hope not then the power to have

Which ingloriously you used.

Think not, Thyrsis, I will e’er

10 By my love my empire lose.

You grow constant through despair,

Kindness you would soon abuse.

Though you still possess my heart,

Scorn and rigor I must feign.

15 There remains no other art

Your love, fond fugitive, to gain.

You that cou’d my Heart subdue,

To new Conquests ne’re pretend,

Let your example make me true,

20 And of a Conquer’d Foe, a Friend

Then if e’re I shou’d complain,

Of your Empire,or my Chain

Summon all your pow’rful Charmes,

And sell the Rebelin your Armes.

2 scorn and… disdain: cf. ’LADY WISHFORT: … a little Disdain is not amiss; a little Scorn is alluring’ (Congreve, The Way of the World (1700), III 164-5).

9-10 love… empire: the speaker refuses to cast herself as heroine in a Restoration heroic drama; cf. ’ZEMPOALLA: Were but this stranger kind, I’d… give my Empire where I gave my heart’ (Sir Robert Howard and John Dryden, The Indian Queen. A Tragedy (1664), IV i 55-6). Since Elizabeth Malet was an heiress, ‘worth… 2500l. per annum’ (Pepys, 28 May 1665), her ‘empire’ was no fiction.

24 sell: Walker emends ‘sell’ to ‘fell’ (Rochester 1984, 22); ‘quell’ may be the word intended; cf. quell a rebellion.

From Mistress Price, Maid of Honour to Her Majesty, mho sent [Lord Chesterfield] a Pair of Italian Gloves (My Lord, These are the gloves that I did mention)

Nicholas Fisher points out that the poem adopts the three-part structure and dramatic situation of Ovid’s Heroides (375), but unexpectedly puts the woman in complete control of the situation (Classical and Modern Literature 11 (1991), 341–3).

7 Bretby: Bretby Park was the Chesterfield estate in Derbyshire.

Under King Charles H’s Picture (I, John Roberts, writ this same)

1 writ: in the obsolete sense of’draw the figure of (something)’(OED).

3 by name: Rochester may be mimicking Roberts’s actual speech or mocking the traditional English carol: ‘That there was born in Bethlehem, / The Son of God by name’; ‘born of a virgin, / Blessed Mary by name’ (Oxford Book of Carols, ed. Percy Dearmer et al. (1928), 25, 62).

To his more than Meritorious Wife (I am by fate slave to your will)

1-2 I am by fate slave to your mill And shall be most obedient still: the ‘hyperbolic compliment’ (303) of the first two lines is undercut by the comic double rhymes, ‘compose ye… a posy’, ‘duty… true t’ye’, and ‘speeches… breeches’ (pronounced ‘britches’), that follow.

8 Yielding…the breeches: surrendering the authority of a husband (Tilley B645)

10 Jan: Rochester’s surviving letters to his wife are signed ‘Your humble servant Rochester’ or ‘R’.

Rochester Extempore (And after singing Psalm the 12th)

1 Psalm the 12th: Psalm 12, signed T[homas] S[ternhold] begins: ‘Help, Lord, for good and godly men / do perish and decay: / And faith and truth from worldly men / is parted clean away’ (Sternhold and Hopkins, The Whole Book of Psalms, Collected into English Metre (1703), sig. A4r).

6 I am a rascal, that thou know’st. Defoe quotes this line in the Review of 14 February 1713, attributing it to ‘Lord Rochester’s Confession to his Penitentials’; rascal: this ancestor of Robert Burns’s Holy Willie is equally ‘fash’d wi’ fleshly lust’.

Spoken Extempore to a Country Clerk after having heard him Sing Psalms (Sternhold and Hopkins had great qualms)

1 Sternhold and Hopkins: Thomas Sternhold (d. 1549) and John Hopkins (d. 1570) collaborated to produce a metrical version of the Psalms (c. 1549) which survived in the next age as the standard for bad poetry (Thomas Brown, The Works (1711), IV 163–5).

The Platonic Lady (I could love thee till I die)

This exercise in octosyllabic couplets is an adaptation of some verses attributed to Petronius (Oldham 1987, 462):

A Fragment from Petronius Translated

Doing, a filthy pleasure is, and short;

And done, we straight repent us of the sport:

Let us not then rush blindly on unto it,

Like lustfull beasts, that onely know to doe it:

For lust will languish, and that heat decay.

But thus, thus, keeping endlesse Holy-day,

Let us together closely lie, and kisse,

There is no labour, nor no shame in this;

This hath pleas’d, doth please, and long will please; never

Can this decay, but is beginning ever.

(Jonson 1925–52, VIII 294)

The title is ironical. What the lady advocates is not platonic love, ‘free from sensual desire’(OED), but coitus reservatus (Sanskrit karezza), in which ‘by a technique of deliberate control [i.e. ‘the art of love’ (1. 6)] …orgasm is avoided and copulation thereby prolonged’ (OED, s.v. coitus).

7 enjoyment: ejaculation, which ‘Converts the owner to a drone’ (1. 12).

11–12sting… gone… drone: cf. ‘If once he lose his sting, he grows a Drone’

(Cowley, Against Fruition (1668), 32).

17what: penis.

23-4Let’s practise then and we shall prove These are the only sweets of love: Possibly a parody of Marlowe’s ‘Come live with mee and be my love, / And we will all the pleasures prove’ (The Passionate Pilgrim (1599), sig. D5) (Rochester 1953, 228).

Song (As Cloris full of harmless thought)

23 the lucky minute: cf. ‘Twelve is my appointed lucky Minute, when all the Blessings that my Soul could wish Shall be resign’d to me’ (Aphra Behn, The Lucky Chance (1686?; 1687), 58); ‘Lovers that… in the lucky Minute want the Pow’r’ (Samuel Garth, The Dispensary (1699), POAS, Yale, VI 735). Treglown isolates a lucky Minute/happy Time/Shepherd’s Hour sub-genre of seventeenth-century erotic lyric and cites examples including Sir Carr Scrope’s song in The Man of Mode (1676) (cf. headnote above), John Glanvill’s The Shepherd’s Hour (1686), and Dryden’s song in Amphitryon (1690), IV i: A Pastoral Dialogue betwixt Thyrsis and Iris (Treglown 1982, 86–7). ‘The Lucky Minute’ also became a popular tune title (Simpson 1966, 106).

Song to Cloris (Fair Cloris in a pigsty lay)

8 ivory pails: the rarity and expensiveness of ivory (£167 per hundredweight in 1905) makes these ivory swill buckets a refinement of mock-epic proportions, like the ivory gate through which Cloris’s false dream reaches her (Odyssey, XIX 562; Aeneid, VI 895).

15 Flora’s cave: the cave in which the Greek nymph Chloris is raped by Zephyrus, the west wind, and from which she emerges as Flora, the Roman goddess of flowers and spring (Ovid, Fasti, V 19s). The cave is Ovid’s and the hymeneal gate may be Shakespeare’s (The Winter’s Tale (1609–10; 1623), I ii 196–8), but the phallic pig appears to be Rochester’s.

31 piercè;d: one reader wishes that this dream of rape had been a real rape ‘perhaps’ (Felicity Nussbaum, The Brink of All We Hate (1972), 62); zone: literally ‘any encircling band’ (OED, citing Francis Quarles, Emblemes (1635), 274: ‘untie / The sacred Zone of thy Virginity’), cf. Aphrodite’s zone which creates ‘the lucky minute’ (2i.223) for anyone wearing it (Iliad, XIV 214-16, trans. Richmond Lattimore, ‘the elaborate, pattern-pieced / zone …[the] passion of sex is there’); figuratively that part of the body around which a girdle is fastened; cf. pelvic girdle.

39 legs: the moral disorder is reflected in a rhyming disorder, ‘frigs… pigs… legs’, that is unique in the poem.

40 innocent and pleased: virgo intacta and sexually satisfied.

To Corinna (What cruel pains Corinna takes)

7 the silly art: coyness, ‘Affected rules of honour’ (I. 12)0.

9 tyrant, virtue.

13 she: Corinna.

Song (Phillis, be gentler, I advise)

2 Make… time: ‘The poem is identical in form, length and, it at first seems, subject matter, to the famous lyric recalled by the second line, Herrick’s “To the Virgins, to make much of Time”… Yet there could not be a greater difference between them in substance or in tone… ; while Herrick’s poem is rooted in the present… Rochester’s cruelly anticipates what is in store in the future: faded beauty, scandal, ruin, and death’ (Treglown 1980,24). 4time to repent. Rochester’s alleged deathbed repentance is described in Parsons 1680, I–37.

15–16 Die with the scandal of a whore, And never know the joy: quoted in Defoe, An Elegy on the Author of the True-Born-English-Man (1704), 32.

22–3 joys… improved by art: cf. 97.16n. and ‘All that art can add to love’ (46’ 24).

Could I but make my wishes insolent

Although the poem has been called an epistle, it is not an epistle. Lines 1-6 address the reader about ‘her’ (1. 6) in the third person. Lines 7–26 address her in the first person, ‘you… your’ (11. 11,17,26). Lines 1–6 are a kind of proem to the dramatic monologue that follows. After 11. 14–16 the switching of skirts can be heard.

6 lay hold of her: cf. ‘lay hold on her, and lie with her’ (Deuteronomy 22.28).

7–8 spirit… merit: imperfect rhyme and the unique double rhyme make this couplet outstanding in the poem. The metre, stretching out ‘fa-MIL-i-AR’ over two full iambs, makes this the outstanding word in the couplet. ‘Familiar’ is what the speaker designs to be.

9 blundering… Phaëton: the son of Helios (the sun) and Klymene, ‘foolish Phaeton… doest desire… A greater charge than any God coulde ever have’ (Ovid, Metamorphoses (1567), f. 15), namely, to drive the chariot of the sun. The horses bolted and Phaeton was destroyed.

15 what he next must say: cf. ‘think what next to say’ (26.113).

The gods by right of nature must possess

In the opening speech of Shadwell’s The Virtuoso (25 May 1676; 1676) Bruce, the hero, apostrophizes ‘great Lucretius’, the patron saint of gentlemen of wit and sense like Bruce himself and Shadwell and Shadwell’s friend Rochester. ‘Almost alone’, Bruce says, Lucretius demonstrates ‘that Poetry and Good Sence may go together’ (Shadwell 1927, III 105).

5-6 Rich in themselves, to whom we cannot add, / Not pleased by good deeds nor provoked by had: De rerum natura, II 650–51); cf. ‘[Rochester] could not see that there was to be either reward or punishment’ (Burnet 1680, 52); cf. 23.3–5.

To Love (O Love! how cold and slow to take my part)

The translation of Ovid’s Amores, II ix provides a kind of bill of fare for Rochester’s major love poems, which celebrate not the acts but the mishaps of love, ‘Love’s fantastic storms’ (1. 37): premature ejaculation (15), falling in love with a whore (21.125), the fear of inadequacy (43,’o-io), falling in love with an old man (45).

Epigraph: the first line of Ovid’s Amores, II ix: ‘O Cupid, who never can be sufficiently reviled’.

4 They murder me: cf. ‘They flee from me, that sometime did me seeke’ (Sir Thomas Wyatt in Songs and Sonnets (1585), f. 22r.

9 give o’er: leave behind the birds taken and press on for more.

13–14 disarmed… disarmed: Rochester imitates the Ovidian ‘turn’, as Dryden called it, but not the striking Ovidian image: ‘in nudis… / ossibus? ossa mihi nuda’ (on naked bones… my bones naked) (Amores, II ix 13–14).

15 dull: without love; the word translates Ovid’s phrase ‘sine amore’; scornful maids: cf. ‘she who scorns a Man, must die a Maid’ (Pope 1930–67, II 197).

17–18 ‘Since Roma and Amor are palindromes, Ovid may be making the witty point that their opposite behaviour is natural’ (Francis Cairns, in Creative Imitation and Latin Literature, ed. David West et al. (1979), 126).

21–2 whore… to he a bawd: ‘[Ovid’s] images of ships laid up in dock and of a retired gladiator exchanging his sword for a practice foil are replaced by the distinctively Restoration’ whore who graduates to a bawd (Love 1981, 143).

25 in Celia’s trenches: Rochester’s phrase has no counterpart in Ovid, but does occur in Priapea, XLVI 9: ‘fossas inguinis ut teram dolemque’ (labour in that ditch between your thighs); cf. ‘said my uncle Toby – but I declare, corporal, I had rather march up to the very edge of a trench – A woman is quite a different thing – said the corporal. – I suppose so, quoth my uncle Toby’ (Sterne 1940, 583).

44–50 cf. in lazy slumbers blest /… happy… whilst I believe:

And slumbring, thinks himselfe much blessed by it.

Foole, what is sleepe but image of cold death,

Long shalt thou rest when Fates expire thy breath.

But let me crafty damsells words deceive,

Great joyes by hope I inly shall conceive.

(C[hristopher] M[arlowc], All Ovids Elegies [c. 1640], sig. C5r)

60 vassal world: Rochester (but not Ovid) closes the poem by bringing it back to Rome’s ‘wide world’ (I. 17): if Cupid could make women love, his domination of the world of lovers would be as complete as Rome’s domination of the world of nations.

The Imperfect Enjoyment (Naked she lay, clasped in my longing arms)

A poem on the premature ejaculation mishap was almost an obligatory exercise for the Restoration poet. George Etherege, Aphra Behn, William Congreve, and three anonymous poets cranked out examples, but Rochester’s is the funniest.

1 Naked she lay: ‘She lay all naked in her bed’ was the title of a popular tune (Simpson 1966, 657).

3–4 equally inspired… eager fire, /… kindness… flaming… desire: heightened interest and intensity in Rochester’s verse are frequently accompanied by heightened sound effects, particularly assonance (’equally… eager’, ‘inspired… fire… kindness… desire’) and alliteration (’fire… flaming’); cf. ‘balmy brinks of bliss’ (I. 12) and ‘I… alive… strive: / I sigh… swive’ (II. 25–7).

18 Her hand, her foot, her very look’s a cunt: cf. The Conquest of Granada I (December 1670; 1672), III i 71: ‘Her tears, her smiles, her every look’s a Net’ (Dryden 1956– , XI 47) (Treglown 1976, 555).

19 Smiling: decorum does not permit her to laugh.

22–3 ‘Is there then no more?’ / She cries: cf. ‘Why mock’st thou me she cry’d?’ (C[hristopher] M[arlowe], All Ovids Elegies [c. 1640], sig. E2v).

23 this: foreplay.

23–4 love… pleasure: ‘We’d had more pleasure had our love been less’ (Etherege, 1963, 8).

27 I sigh, alas!… but cannot swive: in the Garden of Eden ‘Each member did their wills obey’ (43.7); cf. ‘How just is Fate… / To make him Love the Whore he cannot Please’ (Defoe, The Dyet of Poland (1705), POAS, Yale, VII 119).

29 shame: cf. ‘To this adde shame… / The second cause why vigour faild me’ (Marlowe, op. cit., sig. E2r).

30 impotent: both rhyme scheme and metre require that the third syllable be fully accented, ‘IM-po-TENT’, prolonging and emphasizing the crucial word in the poem.

31 her fair hand: cf. ‘Her touch could have made Nestor young again’ (Ovid, Amores, III vii 41).

45 withered flower: cf. ‘member… more withered than yesterday’s rose’ (Ovid, Amores, III vii 65–6). Rochester omits Ovid’s nice detail of the prostitute thoughtfully spilling water so her maid would not know of her client’s failure, and substitutes the frightful curse, which is not in Ovid. When he is rescued from Orgoglio’s dungeon, the Red Crosse knight is ‘Decay’d, and al his flesh shrank up like withered flowres’ (Spenser, The Faerie Queene (1590), I viii 41) (John H. O’Neill, Tennessee Studies in Literature 25 (1980), 63).

46 base deserter of my flame: cf. ‘nefande destitutor inguinum’ (unspeakable deserter of my loins) (Tibullus 1971, 174). The transition from history of the recreant member to apostrophe to the recreant member (II. 46–72) may recall Marvell’s An Horatian Ode upon Cromwell’s Return from Ireland (1650; 1681) which also moves from history of a recreant Member (II. 1–112) to apostrophe to a recreant Member (II. 113–20).

48 magic: cf. ‘Why would not magic arts be the cause of my malfunction?’ (Ovid, Amores, III vii 35).

50 oyster, cinder, beggar: apparently shorthand for oyster-wench, cinder-woman, London beggar; cf. ‘Oyster, Beggar, Cinder Whore’ (Defoe, Reformation of Manners (1702) (POAS, Yale, VI 408).

54–7 hector in the streets /… hides his head: Quaintance suggests that these lines expand Remy Belleau’s phrase, ‘Brave sur le rempart et couard à la brèche’ (Bold on the battlements, coward in the breach) (PQ 42 (1963), 191).

54 hector: in June 1675 Rochester ‘in a frolick after a rant [a bombastic speech] did… beat downe the dyill which stood in the middle of the Privie [Gardjing, which was esteemed the rarest in Europ’ (Davies 1969, 351). Whereupon John Oldham wrote A Satyr against Venue ‘Suppos’d to be spoken by a Court-Hector at Breaking of the Dial in Privy Garden’ (Oldham 1987, 57–67; cf. Marvell 1927, I 310). Rochester’s words on the occasion have been preserved: ‘Rochester, lord Buckhurst, Fleetwood Shephard, etc. comeing in from their revells. “What!” said the earl of Rochester, “doest thou stand here to [fuck] time?” Dash they fell to worke’ (Aubrey 1898, II 34).

56–7 if his king… claim his aid, / The… villain shrinks: Rochester did not volunteer for service in the third Dutch War (1672–4); cf. 3.17–18.

62 Worst part of me: cf. ‘pars pessima nostri’ (worst part of me) (Ovid, Amores, III vii 69).

On King Charles (In the isle of Great Britain long since famous grown)

Although the custom of fosterage was no longer institutional at the Stuart court, Charles II gave Rochester an allowance of £500 a year while he was at Oxford, chose Dr Andrew Balfour to be his travelling governor, received Rochester at Whitehall upon his return from his travels, provided him lodgings in the palace, appointed him gentleman of the bedchamber with a pension of £1,000 a year for life, and chose for his wife a most sought-after heiress who also wrote verse. In all this the King manifestly acted as foster-father (Ronald Paulson, in The Author in His Work, ed. Louis L. Martz and Aubrey Williams (1978), 117). In his juvenile verse Rochester acknowledged that he owed much more than ‘cold respect’ (3.15) to this distant figure.

The relation between the two, therefore, is the old love–hate business of father and son. Whereas the precocious boy wanted nothing more than to throw away his life for his king the disillusioned adult regarded Charles with ‘a mixture of irony, contempt and genuine affection’ (Pinto 1962,75)

.

4 easiest: cf. ‘This Principle of making the love of Ease exercise an entire Sovereignty in his Thoughts, would have been less censured in a private Man, than might be in a Prince’ (Halifax, 1912, 204) (Rochester 1982, 86).

5 no ambition: cf. ‘the profuseness, and inadvertency of the King hath saved England from falling into destruction’ (A Letter to Monsieur Van B– de M– at Amsterdam, written Anno 1676 by Denzil Lord Holles concerning the Government of England [1676?], 5–6).

6 the French fool: Charles II was negotiating a separate peace with the Dutch (see next note), but Louis XIV carried on the war for four more years.

8 Peace: ‘our King… being always most willing to hear of peace’ (Roger Palmer, Earl of Castlemaine, A Short and True Account of the Material Passages in the late War between the English and Dutch, 2nd ed. (1672), 47), negotiations with the Dutch were opened during the winter of 1672–3 and the Treaty of Westminster was signed on 19 February 1674. The sexual pun on peace/piece could not have displeased Charles II.

11 length: Pepys heard about the King ‘hav[ing] a large- - - - -’ (Pepys, 15 May 1663); cf. ‘his Majesty [is] the most potent Prince in Christendom’ (Carew Reynel, The True English Interest (1674), sig. A6r). The length of Charles’s sceptre was two feet, ten and a half inches (Rochester 1982, 86).

13 brother: James, Duke of York.

14 I hate all monarchs… neither this nor its antithesis, ‘I loathe the rabble’ (68.120) provides evidence of Rochester’s political orientation.

14–15 hate all monarchs… Britain: Vieth (Rochester 1968, 61), Walker, and some of the ms. copies put these lines at the end of the poem, ‘although this gives the poem a perhaps too defiantly republican slant’ (Rochester 1984, 75, 271). But six ms. copies and the copy-text put the lines here, allowing the poem to close with the diminished sexuality of Charles II’s ‘declining years’ (II. 25–33). The reaction to ’all monarchs’ comes more appropriately here at the end of the contrast between Charles II and Louis XIV.

25 declining years: Charles was forty-three on 29 May 1673.

29 hang an arse: ‘hold back’(OED).

32 hands… thighs: cf. ‘my advice to [Nell Gwyn] has ever been this… with hand, body, head, heart and all the faculties you have, contribute to his pleasure all you can’ (Rochester to Henry Savile, June 1678, Rochester Letters 1980, 189).

A Ramble in St James’s Park (Much wine had passed with grave discourse)

The meaning of ‘ramble’ dilucidated below (Title) is essential to understanding the dramatic situation assumed in the opening lines of the poem. There is no reason to identify the speaker with Rochester, who would be unlikely to prowl in St James’s Park ‘unaccompanied by… a purse bearer, a page, and a couple of footmen’ (Love 1972, 161). The chagrin d’amour of this aristocratic speaker (101. Headnote) is that he has fallen in love with a whore with whom he is presently cohabiting (II. 107–32). An historical analogue to this dilemma is provided by the cohabitation of Edward Mountagu, Earl of Sandwich, with Betty Becke, ‘a common Courtizan’, so damaging to Sandwich’s reputation that Samuel Pepys felt compelled to write ‘a great letter of reproof to his patron and kinsman (Pepys, 22 July 1663, 18 November 1663).

Now drunk and overwhelmed with lust for his whore, Rochester’s imagined speaker sallies forth in search of her, i.e. ‘rambles’ in St James’s Park (where presumably he knows that she patrols). He catches up with her just as Corinna picks up three clients and drives off with them in a hackney coach (1. 82), to the speaker’s unspeakable frustration.

Title Ramble: to go looking for a sexual partner; cf. ‘RANGER. Intending a Ramble to St. James’s Park to night, upon some probable hopes of some fresh Game’ (Wycherley 1979, 24) (John D. Patterson, N&Q 226 (1981), 209–10).

4 the Bear: the Bear and Harrow in Bear Yard off Drury Lane (Rochester 1984, 263) was said to be ‘an excellent ordinary after the French manner’ (Pepys, 18 February 1668).

7 St James’s Park: a deer park enclosed with a brick wall, created by Henry VIII and improved by Charles II. The Mall was a wooded alley for playing a mallet game, the Canal was made by damming a tributary of the Thames, and the famous trysting place was the heavily wooded area around Rosamund’s Pond in the south-west corner of the Park.

9 James: presumably James the son of Zebedee, the first apostle to be martyred, whose remains are venerated at Santiago de Compostela.

10 consecrate: cf. ‘how lovingly the Trees are joyned… as if Nature had design’d this Walk for the private Shelter of forbidden Love’ (Colley Cibber, Love’s Last Shift (1696), III ii 2).

19 mandrakes: Rochester’s fancy that mandrake grows up from semen spilled on the ground is a variant of the folklore motif (Motif–Index A2611.5) that mandrake grows up from blood spilled on the ground.

20 fucked the very skies: cf. ‘aged trees /… invade the sky’ (On St. James’s Park, as lately improved by his Majesty (1661) (Waller 1893,170).

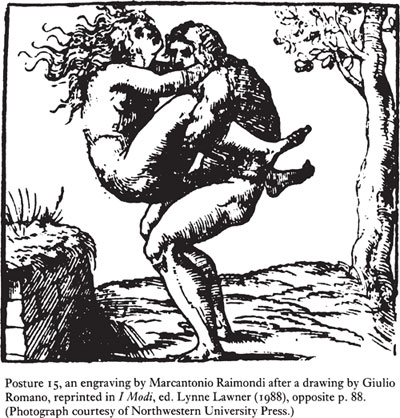

22 Aretine: About 1524 in Rome Marcantonio Raimondi published sixteen engravings after drawings by Giulio Romano of sixteen positions or ‘postures’ of sexual intercourse (afterwards called I Modi). Pope Clement VII insured that this became an extremely rare book by ordering Raimondi to be imprisoned and the plates and copies of Raimondi’s book to be destroyed. After effecting Raimondi’s release, Pietro Aretino (1492–1556), ‘the scourge of princes’, wrote sixteen Sonetti Lussoriosi to illustrate a second edition of Raimondi’s prints (c. 1525) and then fled to Florence. Although Rochester may have been able to buy a copy of this book when he visited Italy (1662–4), no copy of either edition is now known. But about 1527 and probably in Venice a pirated edition of I Modi with Aretino’s sonnets was published and of this edition one copy survives in private hands. A facsimile of this book with English translations of Aretino’s sonnets was edited by Lynne Lawner and published by Northwestern University Press in 1988. Posture 15 is reproduced below.

23–4 shade… made: cf. ‘Methinks I see the love that shall be made, / The Lovers walking in that Amorous shade’ (On St. James’s Park, as lately improved by his Majesty (1661) (Waller 1893, 168) (Rochester 1984, 263)).

26 Whores: of the lowest and highest class. A bulker was a streetwalker who performed on the bulkheads in front of shops. An alcove was a recess in a bedroom for a bed of state (OED).

33 walks: there were walks along Pall Mall, on both sides of the Canal, and around Rosamund’s Pond.

37 charming eyes: cf. ‘eyes, /… make… men their prize’ (On St. James’s Park as lately improved by his Majesty (1661) (Waller 1893, 169)).

44 tails: ‘The simile comparing Corinna to a bitch in heat recurs throughout the poem’ (Paulson 1972, 28).

49–50 Sir Edward Sutton: These lines may be alluded to in Dorset’s Colin (1679): ‘Chance threw on him Sir Edward Sutton, / A jolly knight that rhymes to mutton’ (POAS, Yale, II 168); Banstead: Banstead Downs in Surrey, about fifteen miles south of London, was ‘covered with a short grass intermixed with thyme, and other fragrant herbs, that render the mutton of this tract… remarkable for its sweetness’ (London and Its Environs Described, 6 vols. (1761), I 246); mutton: ‘loose women’ (OED). ‘He loves laced mutton’ is proverbial (Tilley M1338). This is a quibble that Shakespeare found equally irresistible: ‘The Duke (I say to thee againe) would eate Mutton on Fridaies’ (Measure for Measure (c. 1604; 1623), III ii 192).

67–8 comedy… landlady: the first of a series of comic rhymes: ‘arse on… parson’ (II. 91–2), ‘fraternity… of buggery’ (II. 145–6). The grammatical construction here is elliptical: ‘from’ is omitted before ‘the comedy’.

77–8 kiss…‘Yes’: the dissonant rhyme reflects the ‘anatomical distortion’ in the couplet (Farley–Hills 1978, III).

97 natural freedoms: cf. [Rochester] thought that all pleasure, when it did not [hurt another or injure one’s health], was to be indulged as the gratification of our natural Appetites. It seemed unreasonable to imagine these were put into a man only to be restrained, or curbed’ (Burnet 1680, 38).

101 a whore in understanding: Mistress Flareit likewise comes to regard her affair with a fool, Sir Novelty Fashion, as a ‘forfeiture of my Sense and Understanding’ (Colley Cibber, Love’s Last Shift (1696), IV i 52)

102 fools: the word receives heavy rhetorical emphasis as the first term of a crucial contrast with porters and footmen (I. 120). The speaker’s incredulity is emphasized by an incomplete sentence.

114 Drenched: ‘like Juvenal’s Messalina’ (Vieth and Griffin 1988, 60).

116 digestive surfeit water: the speaker’s rage may be expressed by redundancy: the phrase is redundant (surfeit water is a digestive) and II. 117–22 are redundant (they replicate II. 113–16).

119 devouring cunt: cf. Motif–Index F547.1.1 Vagina dentata.

133–66 The pronouncement of the curse on Corinna (Motif-Index M410) is a specialized form of ordaining the future, a kind of malign prophecy. Satire in turn may be a specialized form of pronouncing curses, not on Corinna, of course, but on the system of which Corinna is a sympton.

136 in… fools delight: cf. ‘a Woman who is not a Fool, can have but one Reason for associating with a Man that is’ (Congreve 1967, 399).

138 go mad for the north wind: to fall in love with Boreas, whose sexual exploits include turning himself into a horse, would correspond with the speaker’s mishap in falling in love with Corinna.

142 perish: in orgasm.

143–50 These are the impossible tasks of folklore (Motif-Index H1010) which add up to an emphatic ‘never’.

160 dog-drawn bitch: When a dog and bitch are locked together in mating, the dog may throw a hind leg over the bitch’s back and try to pull away, dragging the bitch behind him with great pain to both (Paulson 1972, 28–9).

165–6 And may no woman better thrive / Who dares profane the cunt I swive: cf. ‘May no man share the blessings I enjoy without my curses’ (Rochester Letters 1980, 123, to Elizabeth Barry).

Song (Love a woman? You’re an ass)

3 happiness: an outrageous chore is emphasized by an outrageous comic rhyme with ‘You’re an ass’ (I. 1).

4 idlest: Harvard MS. Eng. 636F, p. 247 and Rochester 1691,44, derived from it, reads ‘silliest’, but ‘idlest’, the reading of the copy-text, meaning ‘empty, vacant’ (OED), enforces the geographic image of’God’s creation’.

9 Farewell, woman!: cf. ‘Two Paradises ‘twere in one / To live in Paradise alone’ (Marvell 1927,I 49). Both Marvell and Rochester are bluffing.

Seneca’s Troas, Act 2. Chorus (After death nothing is, and nothing, death)

1 After death nothing is, and nothing, death: Rochester translates the first line literally: ‘Post mortem nihil est ipsaque mors nihil’ (Seneca, Troades, 397); cf. ‘Nil igitur mors est ad nos… scilicet haud nobis quicquam’ (Therefore death is nothing to us… nothing at all will be able to happen to us) (Lucretius, De rerum natura. III 830, 840).

8 become… lumber: cf. ‘maior enim turbae disiectus material / consequitur… materies opus est ut crescant postera saecla’ (a greater dispersion of the disturbed matter takes place at death… matter is needed that coming generations may grow) (ibid. III 928–9,967).

10 Where… things unborn are kept: ‘quo non nata iacent’ (where they lie who were never born) (Seneca, Troades, 408).

11 Devouring time swallows us whole: ‘A few phrases from… Troades englished, by Samuel Pordage, published in 1660 while Rochester was still at Wadham, seem to have remained in his mind: “Time us, and Chaos, doth devour” [I. 11], “Body and Soul [I. 12], and “idle tailes” [I. 17]’ (Rochester 1984, 255).

13–18 Hell and the foul fiend… / Are senseless stories… / Dreams: ‘Taenara et aspero / regnum sub domino limen et obsidens / custos non facili Cerberus ostio / rumores vacui verbaque inania / et par sollicito fabula somnio’ (the underworld, the savage god who rules the dead, and the dog Cerberus who guards the exit, are empty words, old wives’ tales, the stuff of bad dreams) (Seneca, Troades, 402–6); cf. ‘nil esse in morte timendum… nec quisquam in barathrum nec Tartara deditur atra… nec miser inpendens magnum timet acre saxum / Tantalus, ut famast… nec Tityon volucres ineunt Acherunte iacentem’ (there is nothing to be feared after death… There is no wretched Tantalus, as the story goes, fearing the great rock that hangs over his head… No Tityos lying in Acheron is ravaged by winged creatures)

(Lucretius, De rerum natura, III 866, 966, 980–81, 984); no more: cf. ‘there is no naturall knowledge of mans estate after death; much lesse of the reward that is then to be given… but onely a beliefe grounded upon other mens saying’ (Hobbes 1935, 100). Rochester told Burnet that ‘he could not see there was to be either reward or punishment’ after death (Burnet 1680, 52)

.

Tunbridge Wells (At five this morn when Phoebus raised his head)

Tunbridge Wells, about thirty miles south-east of London, is the site of chalybeate springs supposed to have medicinal properties. It became a fashionable resort after visits by King Charles and Queen Catherine (Pepys, 22 July 1663) and by the Duke and Duchess of York with the Princesses Mary and Anne in 1670.

The poem seems experimental in several ways at once. It may be a parody of the Virgilian loco-descriptive poem, examples of which includeTo Penshurst (1616), with its ‘walkes for health as well as sport’ (Jonson 1925–52, VIII 93) and Waller’s reprise, At Penshurst (1645) (Waller 1893, 46). But its speaker seems pointedly un-Georgic. He is ‘querulous, foul-mouthed, and dyspeptic, and in no sense… to be identified with [Rochester]’ (Love 1972, 153). He is in fact a perfect satyr, more sympathetic with the equine than with the human race (II. 183–5).

1 At five: cf. ‘the morning, when the Sun is an hour more or lesse high, is the fittest time to drink the water’ (Rowzee 1671, 53).

3 trotted: cf. ‘the nearest good lodgings were at Rusthall and southborough, a mile or two distant from the wells’ (Rochester 1968,73).

14 a stag at rut: ‘the allusion is almost certainly to Sir Robert Howard, who had made himself ridiculous with his pompous poem, The Duel of the Stags’ (1668) (Robert Jordan, ELN 10 (June 1973), 269). Rochester’s friend Henry Savile wrote a parody of Sir Robert’s poem entitled ‘The Duel of the Crabs’ (i.e. of the crab lice) (The Annual Miscellany for the Year 1694: Being the Fourth Part of Miscellany Poems (1694), 293–7).

16 Sir Nicholas Cully: Sir Nicholas, a booby squire, is tricked into marriage with the cast mistress of a London fop in Etherege’s first comedy, The Comical Revenge: or Love in a Tub (1664). The role was created by James Nokes.

24 crab-fish: crabmeat, an aphrodisiac? cf. Tilley C785.

31 Endeavouring: the metre stretches out ‘en-DEAV-our-ING’ into four syllables as the speaker strains to avoid the two knighted fools.

38–9 A tall, stiff fool… / The buckram puppet: cf. ‘He takes as much care and pains to new-mold his Body at the Dancing-Schools, as if the onely shame he fear’d were the retaining of that Form which God and Nature gave him. Sometimes he walks as if he went in a Frame, again as if both head and every member of him turned upon Hinges. Every step he takes presents you with a perfect Puppit-play’ (Clement Ellis, The Gentile Sinner, or, England’s Brave Gentleman: Characterized (1660), 30) (David Trotter in Treglown 1982, 125).

40 as woodcock wise: proverbial (Tilley W746).

44 intrigues: one seventeenth-century spelling, ‘intregues’, may indicate how the word was pronounced: ‘IN-tregues’.

52 Scurvy, stone, strangury: Tunbridge water was supposed to be specific for genitourinary diseases and scurvy (Rowzee 1671, 41, 42).

54 wise: the context requires ‘wise’ to mean ‘fashionable’. This nonce meaning is not recorded in OED, but pushing words beyond the range of their current meanings is Rochester’s practice.

58 ambassadors: cf. ‘the mystery of the gospel, For which I am an ambassador’ (Ephesians 6.19–20) (Rochester 1982, 89).

59 pretend commissions given: apostolic succession, ‘the continued transmission of the ministerial commission, through an unbroken line of bishops from the Apostles onwards’ (OED).

65 Bayes: Samuel Parker; his importance comfortable: Rochester mocks Parker’s coy reference to his wedding plans as ‘Matters of a closer and more comfortable importance to my self’ (Parker, Bishop Bramhall’s Vindication (1672), sig. A2r) (Rochester 1968, 75–6). Marvell wonders ‘What this thing should be’ and concludes that ‘it must be… a Female’ (The Rehearsal Transpros’d (1672), 7–8). The mockery is reinforced by the comic rhyme, ‘all this rabble… comfortable’.

66 archdeaconry: Parker was appointed archdeacon of Canterbury in June 1670.

67 trampling on religious liberty: In A Discourse of Ecclesiastical Polity (1670) (and two later works), Parker assumes an extreme Erastian position, warning ‘how Dangerous a thing Liberty of Conscience is’ (xlvi) and arguing that the unstable nature of man made it ‘absolutely necessary… that there be set up a more severe Government over mens Consciences and Religious perswasions, than over their Vices and Immoralities’ (xliii). He concludes that ‘there is not the least possibility of setting a Nation, but by Uniformity in Religious Worship’ (325).

70 Marvell: this is Rochester’s only surviving reference to the man who said that ‘the earle of Rochester was the only man in England that had the true vaine of satyre’ (Aubrey 1898, II 54).

72 distemper: Parker complains that he was ‘prevented by a dull and lazy distemper’ from replying sooner to The Rehearsal Transpros’d (A Reproof to the Rehearsal Transpros’d (1673), 1). Marvell assumes that the distemper was venereal (The Rehearsal Transpros’d: The Second Part (1673), 8–9) (Rochester 1968, 76). Tunbridge water was specific for ‘running of the reines, whether it be Gonorrhea simplex or Venerea … nay and the Pox also’ (Rowzee 1671, 46–7).

74 sweetness: according to the humours theory (not yet discredited in the seventeenth century), choler was bitter, melancholy sour, blood sweet, etc.; cf. Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), Part I, Section 1, Member 2, Subsection 2.

76 Importance: presumably Parker’s fiancée or wife; see 1. 65n. above.

79 sisters frail: ‘whores’ (I. 5).

82 gypsies: ‘even the late L. of Rochester … was not ashamed to keep the Gypsies Company’ (AND, sig. A8v).

90 conventicle: pronounced ‘CON-ven-TIC-le’ (OED). Dryden rhymes ‘roar and stickle… Conventicle’ (Prologue to The Disappointment (1684), 71).

98 The would-be wit: Sir Robert Howard(?) (I. 18).

99 scrape of shoe: ‘to avoid the horrible absurdity of setting both Feet flat on the Ground, when one should always stand tottering on the Toe, as waiting in readiness for a Congée’ (News from Covent Garden; or. The Town-Gallants Vindication (1675), 6).

101 ruffled foretop: the hair on the crown of a wig dressed in frills.

110 It is your goodness, and not my deserts: cf. ‘MISS: My Lord, that was more their Goodness, than my Desert’ (Swift 1939–68, IV 155).

116 cribbage fifty-nine: having moved her scoring pegs through fifty-nine of the sixty holes on the cribbage board, she was unable to advance to the sixtieth and final ‘game hole’ (Rochester 1968, 77)

123 a Scotch fiddle: ‘The itch’ (OED) of sexual excitement; cf. ‘a Tailor might scratch her where ere she did itch’ (Shakespeare, The Tempest (1611; 1623), II ii 55).

135–6 a barren / Woman… fruitful: cf. ‘there is nothing better against barrenness, and to make fruitful, if other good and fitting means, such as the several causes shall require, be joyned with the water’ (Rowzee 1671, 48).

142 those: menstrual periods.

149 fribbles: cf. ‘MRS BISKET: Ay, Mr. Fribble maintains his Wife like a Lady… and lets her take her pleasure at Epsom two months together. / DOROTHY FRIBBLE: Ay, that’s because the Air’s good to make one be with Child; and he longs mightily for a Child: and truly, Neighbour, I use all the means I can’ (Epsom Wells (1673), II i; Shadwell 1927, II 128) (Robert L. Root, Jr., N&Q 221 (May–June 1976), 242–3).

152 enlarge: by the addition of cuckold’s horns.

153 Cuff and Kick: ‘Two cheating, sharking, cowardly Bullies’ in Epsom Wells, which opened at Dorset Garden on 2 December 1672. In the fifth act, Doll Fribble and Molly Bisket are discovered in bed with Cuff and Kick, respectively.

157 reputation: Gaston Jean Baptiste, comte de Cominges, the French ambassador (1663–65), was not so gullible. The queen is still at Tunbridge, he reported to Louis XIV in July 1663, ‘ou les eaux n’ont rien produit ce qu’il l’en avait espère. On peut les nommer les eaux de scandale, puisqu’elles, on pense, ruinent les femmes et les filles de reputation’ (where the waters have done nothing of what was expected of them. Well may they be called the waters of scandal, for they nearly ruined the good names of the maids of honour and of the married women who were there without their husbands) (J. J. Jusserand, A French Ambassador at the Court of Charles the Second (1892), 89).

158 generation: ‘CUFF: Others come hither to procure Conception. / KICK: Ay, Pox, that’s not from the Waters, but something else that shall be nameless’ (Shadwell 1927, II 107).

165 With hawk on fist: this was Rochester’s father’s disguise, or cover, in his dramatic rescue of Charles II after the defeat at Worcester in 1651 (Clarendon 1707, III 326).

167–9 Rochester’s scorn for the cadets’ posturing is reflected in the scornful rhymes, ‘horse… purse… arse’.

172 Bear Garden ape: the Hope theatre on the Bankside in Southwark reopened in 1664, featuring the blood sports that the Puritans abominated: bull- and bear-baiting, dog- and cock-fights. Pepys found it ‘good sport… But… very rude and nasty’ (Pepys, 14 August 1666). Evelyn agreed that it was a ‘rude & dirty passetime’. Evelyn also mentions ‘the Ape on horse-back’ that ended the evening’s performance (Evelyn, 16 June 1670).

176 what thing is man: cf. ‘Lord, what is man that thou of him / tak’st such abundant care?’ (Sternhold and Hopkins, The Whole Book of Psalms (1703), sig. A3r) (Treglown 1973, 46–7).

180–81 Thrice happy beasts …/ Of reason void: cf. ‘Thrice happy then are beasts… / They only sleep, and eat, and drink, / They never meditate, nor think’ (Thomas Flatman, Poems and Songs (1674), 139) (Thormählen 1988, 404n.); foppery: except for the outlawed gypsies and the Bear Garden ape, everyone in the poem falls under the speaker’s dictum of ‘foppery’, in the extended sense of self-promoting pretence. Although he is called ‘the young gentleman’ (I. 175), the Bear Garden ape does not pretend to be a man.

182 remorse: in the context the word retains something of its etymological meaning, ‘biting back’ (David Trotter in Treglown 1982, 126), encapsulating the satyr-speaker’s response to what he sees and hears at Tunbridge Wells.

Artemisa to Chloe. A Letter from a Lady in the Town to a Lady in the Country concerning the Loves of the Town (Chloe, In verse by your command I write)

7 adventurers for the bays: cf. ‘How vainly men themselves amaze / To win the Palm, the Oke, or Bayes’ (Marvell 1927, I 48).

7–8 adventurers… returns: overseas traders… profits.

17 Bedlam has many mansions: cf. ‘In my father’s house are many mansions’ (John 14.2).

20 discreetly: the net meaning clear of irony is ‘self-destructively’.

24 arrant: an intensifier ‘without opprobrious force’ (Rochester 1984, 278).

40 the most generous passion: Artemisa’s experience in this field (I. 38) suggests that this line be read ironically, articulating Artemisa’s suspicion that love may be a totally selfish, self-absorbing, ungenerous passion.

40–42 Love… / The safe director: a major irony of the poem. Artemisa has lost love (I. 38), Corinna is ‘Cozened… by love’ (I. 191) and degraded, the booby squire is ‘faithful in his love’ (I. 230) and destroyed.

44 That cordial drop: cf. ‘The Cordial Drop of Life is Love alone’ (Pope 1939–67, IV 245).

46–7 raise… subsidies: increase the amount… of grants.

52–3 it… that: love… play, i.e. love now employs as many cheats as gambling.

55 ’Tis: the antecedent is the ‘trade’ (I. 51) of love.

57 gypsies: ‘A contemptuous term for a woman, as being cunning, deceitful, fickle’ (OED) (Rochester 1984, 278). But Artemisa is making another point as well: she observes that women of her class, enjoying all the freedom possible in an ordered society, will nevertheless turn outlaw for the freedom to achieve infamy, which entails the loss of the freedoms enjoyed in an ordered society. Artemisa frames this argument pointedly in an ordered triplet. The choice of infamy is a perverse exercise of free will.

58 hate… infamy: Dustin Griffin suggests ‘hate restraints, even the restraint of avoiding infamy’.

59 They: women who do not live for love (I. 50) by ‘nature’s rules’ (I. 60), but who trade in love.

64 ’Tis below wit… to admire: the Horatian commonplace, ‘nil admirari’ (Epistles, I vi 1); cf. ‘not to be brought by anything into an impassioned state of mind, or into a state of desire or longing’ (Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary (1962), 40).

72 that with their ears they see: i.e. not at all.

83 had been: i.e. ‘would have been’ (Rochester 1980, 92).

96 let me die: the identifying speech tag of Melantha, a heroine in Dryden’s Marriage à la Mode (April 1672?; 1673). ‘A Court-Lady’ in this play is named Artemis. In the dedication of the play to him Dryden acknowledges that it ‘receiv’d amendment’ from Rochester, who also ‘commended it to the view’ of the King (Dryden 1956– , XI 221). Rochester’s ‘amendments’ may have concerned the character of Melantha, whom the fine lady resembles in her affectation (Rochester 1968, 106n.).

98 Embarrassée: cf. ’Melantha:… embarrass me! what a delicious French word’ (Dryden 1956– , XI 300).

99 Indian queen: The Indian Queen, the first rhymed heroic play, by Sir Robert Howard and John Dryden, opened at the Theatre Royal in January 1664. It seems unlikely that the fine lady ‘had turned o’er’ (I. 162) this play, for neither of the queens, Amexia and Zempoalla, are ‘Rude and untaught’.

103–4 à la mode, /… incommode: cf. ‘Un poète à la cour fut jadis à la mode; / Mais des fous aujourd’hui c’est la plus incommode’ (Poets used to be in fashion at court, but today they are the most troublesome fools) (Boileau, Satire I, 109–10) (Davies 1969, 354).

108–9 With searching wisdom, fatal to their ease, / They’ll still find out why what may, should not please: cf. ‘His wisdom did his happiness destroy, / Aiming to know that world he should enjoy’ (47.33–4) (Rochester 1984, 279); They’ll still find out why what may, should not please: although ‘ten low Words’ do creep in this one line, the uncertainty in the third and fourth feet - are ‘why’ and ‘may’ stressed or unstressed? - the cacophony created by ‘why what’ and the internal pause between ‘may, should’ make the line anything but ‘dull’ (Pope 1937–67, I 278).

115 The perfect joy of being well deceived: cf. Ovid, Amores, II x (27.47–8); ‘O yet happiest if ye… know to know no more’ (Milton 1931–8, II i 134); ’Happiness… is a perpetual Possession of being well deceived’ (Swift 1939–68, I 189).

155–7 the very top /… of folly we attain / By curious search: cf. ‘The most ingenious way of becoming foolish is by a system’ (Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, Characteristics (1711), ed. John M. Robertson, 2 vols. (1900), I 189).

166–7 good qualities. . .blest /… so distinguished: ‘the tone of irony’ in these phrases has been noted (David Sheehan, Tennessee Studies in Literature 25 (1980), 77).

183–4 an Irish lord… City cokes: types of booby squire whom Corinna entraps.

194 knew: cf. ‘Adam knew Eve his wife; and she conceived’ (Genesis 4.1).

209 Easter term: one of the four times during the year (from seventeen days after Easter to the day after Ascension Day) when the law courts are in session.

213 country, ‘a district… often applied to a county’ (OED). ‘My young master’s . . .great family’ rules the county by generous provision of ‘strong ale and beef at quarter sessions and general elections.

236–7 complains, / Rails… maintains: ‘Corinna is the subject’ (Rochester 1984, 281).

247 poison him: ‘a conscious or unconscious daydream of disposing of her [the fine lady’s] husband permanently rather than for an afternoon’ (Sitter 1976, 296).

248 in her… arms: when Artemisa to Chloe is scored as an opera, this will be the climactic scene. On stage left of a divided stage in a dumb show the booby squire’s lady and his children are turned away from the door by a servant in night dress. The squire’s lady sinks to the stoop in exhaustion. As it begins to snow she rouses herself to gather the children to her and cover them with her cloak. In a simultaneous action on stage right in a second-floor bedroom the booby squire is discovered in bed with Corinna. He is beginning to feel the effects of poison that Corinna has put into his wine at dinner but rouses himself to sing a passionate aria proclaiming eternal love for Corinna and dies in her arms. She gets up and covers the body with the bed sheet.

261 such stories I will tell: cf. ‘I dare almost promise to entertain you with a thousand bagatelles every week’ (Dryden to Rochester, summer 1673, Rochester Letters 1980, 91).

261–4 tell / swell, I… hell;/… Farewell: after ‘a virtuoso display of poetic technique’ (Howard Weinbrot, Studies in the Literary Imagination 5 (1972), 35) including half lines, half rhymes, single and double rhymes, end-stopped couplets, run-on couplets, and twelve triplets, Rochester ends with a unique, resounding quatrain.

Timon. A Satyr (What, Timon, does old age begin t’approach)

1 A: Auteur in Boileau, Satire III. If the parallel with Boileau were enforced, ll. 1–4 would be spoken by Rochester.

6 th’ Mall: a walk bordered by trees in St James’s Park; cf. ‘Ibam forte Via Sacra, sicut meus est mos / nescio quid meditans nugarum, totus in illis. / accurrit quidam notus mihi nomine tantum, / arreptaque manu’ (Horace, Satire, I ix 1–4) (I was strolling at random along the Via Sacra musing the way I do on some trifle or other and wholly intent thereon, when up runs a man I knew only by name and seizes my hand) (Rochester 1982, 92).

13–32 these lines have no counterpart in Boileau.

15 the praise of pious queens: may be the title of a moralizing broadside.

16 Shadwell’s unassisted… scenes: even before Epsom Wells was performed, it was charged that ‘the best part’ (Shadwell 1927, II 278) had been written by Sir Charles Sedley. Despite Shadwell’s repeated denials, the charge found its way into Mac Fleck-noe (1676; 1682) (Dryden 1956– , II 58).

35–6 Huff, / Kickum: almost a spoonerism for ‘Cuff and Kick’ (48.153).

39 They will… fight: introducing suspense into the narrative.

40 tam Marte quam Mercurio: on the verso of the title-page of The Steel Glas. A Satyre (1576) (Wood 1813–20, I 435–6), George Gascoigne included a portrait of himself in armour with this motto. Walter Raleigh wrote commendatory verses for this volume and after Gascoigne’s death the motto was ‘assumed by, or appropriated to’ Raleigh himself (Biographia Britannica 1747–66, V 3467).

41 I saw my error …too late: cf. ‘trap tard, reconnaissant ma faute’ (seeing mistake too late) (Boileau, Satire III, 37).

42–67 these lines have no counterpart in Boileau.

57 the French king’s success: France and England declared war on the United Provinces in April 1672. In May the French army under the personal command of Louis XIV crossed the Rhine at Tolhuys and occupied three of the seven provinces. Louis XIV established his headquarters at Utrecht on 20/30 June (London Gazette, 20 June 1672) and was only prevented from marching into Amsterdam when William of Orange ordered the polders to be flooded (A Narrative of the Progress of His Most Christian Majesties Armies against the Dutch (1672)). The campaign of 1673 began with the successful reduction of Maastricht, which had been bypassed in 1672. ‘The French Army go on Conquering and get all’, Buckingham complained to the House of Lords in January 1674, ‘and we get nothing’ (Buckingham, Miscellaneous Works(1704), 23).

59 two women: Louise-Françoise de la Vallière (1644–1710) was a maid of honour to Henrietta Anne, Duchess of Orléans, when she became mistress of Louis XIV in 1661. Françoise-Athenais de Rochechouart (1641–1707) married the marquis de Montespan in 1663 and in July 1667 became a mistress of Louis XIV.

73 champagne: the copy-text spelling, ‘Champoon’, may indicate how the word was pronounced.

73–4 French kickshaws …/ Ragouts and fricassees: cf. ‘CLODPATE: I… spend not scurvy French kick-shaws, but much Ale, and Beef, and Mutton, the Manufactures of the Country… I hate French Fricasies and Ragousts’ (Epsom Wells (December 1672; 1673), Shadwell 1927, II 112, 151).

78 The coachman… ridden: this ironic reversal is number 15 of Aretino’s postures (I Modi 1988, 86).

80 tool: dildo; countess: Elizabeth, Countess of Percy.

84 good cheer: cf. a citizen’s idea of a banquet, ‘two puddings’ (Pope 1939–67, III ii 119)

88 Instead of ice: cf. ‘Point de glace, bon Dieu! dans le fort de l’été!’ (No ice? Good God! In the middle of summer?) (Boileau, Satire III, 83).

91–2 table… so large: Boileau’s diners were crowded Boileau, Satire III, 53–4); six old Italians: where the host and hostess and five guests sat, there was room at the table for more than six Romans to recline (Rochester 1982, 93).

95–110 these lines have no counterpart in Boileau.

105 virtuous league: marriage or a discreet affair(?).

108 taste their former parts: one critic finds it impossible to determine whether the effect of the double entendre is ‘malicious ridicule or amused sympathy’ (Love 1972, 163), but the affect of the thirty-odd lines describing the hostess, as powerful as that of A Song of a Young Lady. To her Ancient Lover, seems incompatible with ‘malicious ridicule’.

111 ourselves: Timon includes himself as object of satire, or ‘acknowledg[es] the incompleteness of his isolation’ (Treglown 1982, 83).

112 regulate… the state: cf. ‘Chacun a… réformé l’Etat’ (everyone… remakes the state) (Boileau, Satire III, 162–4). The zeugma, ‘regulate the stage, and… state’, is Rochester’s invention.

114 Mustapha and Zanger die: they commit suicide in Act V of Orrery’s The Tragedy of Mustapha, ‘perhaps composed in half an hour’ (68.97) and produced at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 3 April 1665.

117–18 Halfwit misquotes ll. 269–70 of Orrery’s The Black Prince, which opened at the Bridges Street theatre on 19 October 1667: ‘And which is worse, if worse than this can be, / She for it ne’er excus’d her self to me’. It was said to be ‘the worst play of my Lord Or[r]ery’s’ (Pepys, 23 October 1667).

119 There’s fine poetry: cf. ‘C’est là ce qu’on appelle un ouvrage achevé’ (That’s what you call a finished work) (Boileau, Satire III, 195).

120 So little on the sense the rhymes impose: applied to Orrery the line may mean, Even in rhyme Orrery’s verse remains prosy/prosaic. Applied to Rochester it may mean, Even in rhyme Rochester’s verse retains colloquial word order and cadence; cf. ‘[Rochester] is the first poet in English to write satires… which, however artful their… rhymes, sound like someone talking’ (Treglown 1982, 84).

125 two… plays without one plot: Etherege’s The Comical Revenge; or, Love in a Tub (March 1664) and She wou’d if she Cou’d (February 1668) are the plays. The ‘design’ of the latter was found to be ‘mighty insipid’ (Pepys, 6 February 1668), but both plays have conventional comic plots.

126 Settle, and Morocco: Elkanah Settle’s The Empress of Morocco, rivalling Dryden’s heroic dramas, had two performances at court before the public opening at Dorset Garden on 3 July 1673. Rochester wrote a prologue for the second performance at court.

128–30 Huff misquotes The Empress of Morocco, II i 10, 61–2: ‘Their lofty Bulks the foaming Billows bear …/ Saphee and Salli, Mugadore, Oran, / The fam’d Arzille, Alcazer, Tituan’. Settle had a way with place-names like John Milton: ‘Close sailing from Bengala, or the Isles / Of Ternate and Tidore’ (Paradise Lost (1667, 1674), II 638–9).

132 for Crowne declared: Rochester began to patronize John Crowne in 1671. Crowne dedicated to Rochester his second play, The History of Charles the Eighth of France (November 1671; 1672) with engaging modesty: ‘I have not the Honour of much acquaintance with your Lordship… I have seen in some little sketches of your Pen excellent Masteries… and… I have been entertained… with the wit, which your Lordship sprinkles… in your ordinary converse’ (sig. aiv).

Posture 15, an engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi after a drawing by Giulio Romano, reprinted in I Modi, ed. Lynne Lawner (1988), opposite p. 88. (Photograph courtesy of Northwestern University Press.)

133 the very wits of France: including Gaultier de Coste, seigneur de la Calprenède, Cassandra, the Fam’d Romance, trans. Sir Charles Cotterell (1652); Madeleine de Scudéry, Artamenes; or. The Grand Cyrus, An Excellent New Romance, trans. F. G. (1653–5); Clelia. An Excellent New Romance, trans. John Davies and C. Haven (1655–6).

134 Pandion: Crowne’s first publication was a prose romance modelled on Sidney’s The Countesse of Pembrokes Arcadia (1590) and entitled Pandion and Amphigeneia, or, The History of the Coy Lady of Thessalia (1665).

138–40 Kickum quotes (correctly) The History of Charles the Eighth of France (1672), II i 85–7.

144 The Indian Emperour: Dryden’s fourth play, a sequel to The Indian Queen (January 1664; 1665) with Sir Robert Howard, opened at the Bridges Street theatre in April 1665.

145–6 the lines quoted (correctly) by Kickum are spoken by stout Cortez in The Indian Emperour, I i 3–4; Walter Scott also found them ‘ludicrous’ (Dryden 1882–93, II 319).

150 laureate: Charles II appointed Dryden poet laureate and historiographer royal on 18 August 1670.

152 Souches: for some weeks after 9 April 1674 it was expected in London that Ludwig Ratuit von Souches (1608–82), commander of the Imperial Army on the Rhine, would engage Turenne at the head of the French army. This expectation was dashed when the Imperial Army was diverted into Flanders (London Gazette, 8 June 1674) (Harold F. Brooks, N&Q 174 (May 1938), 384–5).

159–60 courage …/ ’Tis a short pride: cf. ‘[No] Virtue… can we name, / But what will grow on Pride’ (Pope 1939–67, III i 78).

168–9 at t’other’s head let fly / A greasy plate: cf. ‘Lui jette pour défi son assiette au visage’ (He hurls his plate in his face as a challenge) (Boileau, Satire III, 214).

174 Their rage once over, they begin to treat: cf. ‘Et, leur première ardeur passant en un moment, / On a parlé de paix et d’accommodement’ (Their anger was soon dispersed and they began to talk of peace and accommodation) (Boileau, Satire III, 227–8).

A Dialogue between Strephon and Daphne (Prithee now, fond fool, give o’er)

31 change: cf. ‘to be / Constant, in Nature were Inconstancy’ (Cowley, The Mistress (1656), 19–20) (Rochester 1984, 231).

33–40 Since it has not always been understood (R. N. Parkinson, Archiv fur das Studium der Neueren Sprache und Literaturen 207 (August 1970), 142), the tenor of this meteorological metaphor may be noted; it is love-making, from inflammatory foreplay to ‘quiet’ afterglow.

38 Like meeting thunder we embrace: because it is the only iambic tetrameter line in the last sixty-four lines of the poem and because of its imperfect rhyme, this line calls appropriate attention to itself as the climax of the sound effects of the poem and of the love-making within the metaphor.

50 sincere: the imperfect rhyme may call into question the sincerity of Daphne’s successor; cf. 11. 55–6.

51 Gentle, innocent, and free: ‘What Strephon means… is “promiscuous"’ (Treglown 1980, 22).

68 false: critics wonder whether Daphne is lying (Righter 1968, 63; Treglown 1980, 22), raising the further possibility that the poem is a version of the Cretan Liar paradox.

71–2 discovers… lovers: the unique double rhyme points the moral of the fable, which is promptly annulled by the rest of the poem in which Strephon’s deceit is so carefully balanced against Daphne’s deceit that there is nothing to choose between them.

The Fall (How blest was the created state)

Basic to the mishaps of love is die anxiety of lovers, the fear of malfunction, against which Adam and Eve were secured in ‘the created state’. The irony is one of which Milton would not have disapproved: by an act of disobedience to God, Adam and Eve forfeited the obedience of their own bodies. For purposes of the poem Rochester may have assumed something that he did not believe. ‘He could not apprehend’, he told Burnet, ‘how there should be any corruption in the Nature of Man, or a Lapse derived from Adam’ (Burnet 1680, 72). This fact may switch the tone of the poem from tragicomic to straight comic.

1–2 the created state / Of man and woman: Rochester alludes to unfallen sexuality, celebrated in Book IV of Paradise Lost (1667, 1674), ‘Whatever Hypocrites austerely talk’ (IV 744). But Milton says nothing about ‘desire’ or ‘pleasure’ until after the Fall (IX 1013, 1022) and of course never anything about ‘members’.

8 wish: Marvell’s wish was ‘To live in Paradise alone’ (Marvell 1927, I 49).

13–14 duty …/ The nobler tribute: cf. ‘Returning thee the tribute of my dutie’ (Samuel Daniel, Delia (1592), sig. Bir) (Thormählen 1988, 406n.); a: the copy-text reads ‘my’, but the indefinite article needed to complete the parallel, ‘a heart… a frailer part’, survives in three manuscripts.

The Mistress (An age in her embraces passed)

1–2 An age in her embraces …/ Would seem a winter’s day: Rochester may recall these lines in The Mistress about the opposite effect of love: ’Hours of late as long as Days endure, / And very Minutes, Hours are grown’ (Cowley 1905, 93), but the concept of value time, as expounded by E. M. Forster, is not unfamiliar: ‘there seems something else in life besides time, something which may conveniently be called “value”, something which is measured not by minutes or hours, but by intensity’ (Aspects of the Novel (1927), 28). Sterne’s novels are constructed on this principle: ‘a colloquy of five minutes, in such a situation, is worth one of as many ages, with your faces turned towards the street’ (Sterne 1928, 24); a winter’s day: cf. ‘lovers… get a winter-seeming summers night’ (Donne 1912, I 39).

5 But oh, how slowly minutes roll: the pause after ‘oh’ and the assonance, ‘oh… slow… roll’, make the sound imitate the sense.

7 love… is my soul: cf. ‘Love which is …Soul of Me’ (Cowley 1905, ).

12 living tomb: cf. ‘in this [flesh] our living Tombe’ (Donne 1912, I 258).

15 shades of souls: an impossibility; being immaterial, souls cast no shadows.

15–16 On shades of souls and heaven knows what: / Short ages live in graves: Time seems short in his mistress’s embrace but very long in the intervals between embrace Compared with the interminable length of time between embraces, the time spent in the grave (eternity) seems short: ‘Short ages live in graves’.

26 Love raised to an extreme: cf. ‘the extremities of… Love’ (Cowley 1905, 66).

32 pain can ne’er deceive: cf. Dostoyevsky’s Underground Man who argues that if a man invariably chooses pleasure, he is an automaton, programmed for pleasure, ‘a kind of piano key’. Only by choosing pain can a man ‘confirm to himself… that men are still men, and not piano keys’ (Notes from Underground, trans. Mirra Ginsburg (1974), 26. 34)

A Song (Absent from thee I languish still)

7–8 try / That tears: i.e. ‘undergo for tearing’; That: the antecedent is ‘mind’ (1. 6).

9 When wearied with a world of woe: ‘certainly the worst line in Rochester’ (Farley-Hills 1978, 80); cf. Tennyson, Despair (The Nineteenth Century10 (November 1881), 631): ‘were worlds of woe’.

15 Faithless: the most important word in the stanza is emphasized (1) by the substitution of a trochee for an iamb, (2) by alliteration, ‘fall… Faithless… false… unforgiven’ (11. 14–15), and (3) by internal rhyme, ’Lest… unblest . . . Faithless to… rest’ (11. 13–16).

16 my everlasting rest: cf. ‘here / Will I set up my everlasting rest’ (Romeo and Juliet, V iii 109–10).

A Song of a Young Lady. To her Ancient Lover (Ancient person, for whom I)

Rochester imagines a young woman who has already committed herself to a man who is older but not yet ‘Ancient’: ‘Long be it ere thou grow old’, the girl says (Wilcoxon 1979, 147). By speaking in the person of the young woman, Rochester is able to avoid the judgemental tone of the paradox and to go beyond paradox to the amoral realm of low comedy ‘that neither apportions blame nor gives approval’ (David Farley-Hills, The Benevolence of Laughter (1974), 138; Edith Kern, The Absolute Comic (1980), 75).

The arrangement of the heptasyllabic couplets in stanzas of increasing length reduces the ‘Song’ element of the title but provides the vehicle for a submerged metaphor in the poem, as Vieth hints (Tennessee Studies in Literature 25 (1980), 48).

18 From…ice… released: the girl’s ‘art’ restores ‘nature’ as May restores January every year; art and nature coalesce.

A Satyr against Mankind (Were I (who to my cost already am))

There is some point in retaining the old spelling ‘Satyr’ in the title of this poem. If it is a satyr speaking, then a creature half-man and half-animal is saying that he would rather be all animal. The urgent reasons that he gives for his choice constitute the argument of the poem. The conclusion of the argument, that the difference between the ideal man and the average man is greater than that between man and animal, or that most men are inferior to animals, is more pointed if spoken by a satyr. ‘The bolder the better’, as Swift said of paradoxes. ‘But the Wit lies in maintaining them’ (Swift 1939–68, II 101).

Another reason to retain the old spelling is to remind ourselves that the speaker of the poem is no more the Earl of Rochester (Davies 1969, 350–51) than he is Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux, whose Satire VIII (1668) is very distantly imitated in these verses. He is a personated figure, ‘querulous, foul-mouthed, and dyspeptic’, like the satyr-speaker in Tunbridge Wells (Love 1972,153).

3 spirit: cf. ‘For Spirits when they please / Can either Sex assume, or both… in what shape they choose’ (Milton 1931–8, II 23); share: a possible pun similar to part/privy part; the os pubis was called the share bone, and the share was the groin (OED, s.v. Share, sb.2).

5 bear: cf. ’Bears are better / Then Synod-men’ (Butler 1967, 97).

6 anything but that vain animal: cf. ‘Make me anything but a man’ (Menander, Frag. 23) (John F. Moore, PMLA 58 (June 1943), 399).

7 so proud of being rational: cf. ‘An ill dream, or a cloudy day, has power to change this wretched creature, who is so proud of a reasonable soul’ (Dryden, Dedication of Aureng-Zebe (17 November 1675; 1676) (Dryden 1882–93, V 199).

9 sixth: the sixth sense in this context is not ‘a supposed intuitive faculty’ (OED), but reason itself. Hobbes is certain that reason is not a sense: ‘Reason is not as Sense… borne with us… but attayned by Industry’ (Hobbes 1935, 25).

10 certain instinct: cf. ‘Reason raise o’er Instinct as you can, / In this ’tis God directs, in that ’tis Man’ (Pope 1939–67, II i 101).

12–14 Reason, an ignis fatuus… wandering ways it takes: cf. ‘Metaphors, and senselesse and ambiguous words, are like ignes fatui; and reasoning upon them, is wandering amongst innumerable absurdities’ (Hobbes 1935, 26). 15 fenny… thorny: is Rochester parodying Milton’s ‘craggy… shaggy… mossy… mazy’ pastoral vocabulary (Milton 1931–8, II i 48, 126; 114, 201, 158, II ii 281; II i 115, II ii 266)?

18–19 from thought to thought: cf. ‘Mais l’Homme sans arrest, dans sa course insensée / Voltige incessament de pensée en pensée’ (Boileau, Satire VIII, 35–6) (But sillier Man, in his mistaken way …/ His restless mind rolls from thought to thought) Oldham 1987, 163); cf. ‘Sinking from thought to thought’ (Pope 1939–67, V 278); falls headlong down / Into… boundless sea: cf. ‘c’est la voye par où il s’est precipitèe à la damnation eternelle’ (the way whereby man hath headlong cast himselfe downe into eternall damnation) Montaigne, The Essays, trans. John Florio (1603), 288; cf. ‘Hurld headlong… down / To bottomless perdition’ (Milton 1931–8, II i 10).

25–8 Old Age and Experience… make him understand, / That all his life he has been in the wrong: Goethe quotes ‘jenem schrecklichen Texte’ (those frightful words) in Aus meinem Leben: Dichtung und Wahrheit (1811–33), III xiii; Defoe quotes I. 28 only in the Review, 12 December 1704.

29 Huddled in dirt: cf. ‘lodged here in the dirt and filth of the World’ (Montaigne 1700, II 190); engine: a commonplace of contemporary medical theory, cf. We are ‘forced therefore to consider the body of Man, not only as an Engine of curious and admirable workmanship… But also as a Machine’ (Thomas Coxe, A Discourse, wherein the Interest of the Patient in Reference to Physick and Physicians is soberly Debated (1669), 276).

33 wisdom did his happiness destroy: cf. ‘Knowing too much long since lost Paradise’ (Suckling 1971, I 37) (Thormä hlen 1988, 402); ‘happiest if ye seek / No happier state, and know to know no more’ (Milton 1931–8, II i 134).

34 that world he should enjoy: cf. ‘enjoy /… this happie state’ (ibid., II i 162).

39 threatening doubt: fear (1. 45) that the joke is on them.

43 escape: i.e. when the joke is not on them (this time). Sir Carr Scrope may allude to these lines in In Defense of Satire (1677): ‘Each knave or fool that’s conscious of a crime, / Though he ‘scapes now, looks for’t another time’ (POAS, Yale, I 368).

49 Against… wit: cf. ‘these men… who turn all things into Burlesque and ridicule… are too witty… to embrace the principles of Christianity’ (Thomas Smith, A Sermon of the Credibility of the Mysteries of the Christian Religion (1675, 10).

50–71 The adversary’s argument is blunted by a series of imperfect rhymes: ‘care… severe, heaven… given, soaring pierce… universe, there… fear’.

56 grand indiscretion: the speaker’s attack on reason (II. 8–30).

61 everlasting soul: Rochester ‘thought it more likely that the Soul began anew’ in the procreation of each person (Burnet 1680, 65).

62–3 maker… from himself… did the image take: cf. ‘Soul that spiritual Image wherein the Divine likeness doth shine’ (Nathaniel Ingelo, Bentivolio and Urania (1660), 238).

64–5 in shining reason dressed / To dignify… above beast: cf. ‘not prone / And Brute as other Creatures, but endu’d / With Sanctitie of Reason’ (Milton 1931–8, II i 229).

66–7 Reason… beyond material sense: cf. ‘elevated beyond things of corporeal sense, [the mind] is brought to a converse and familiarity with heavenly notions’ (Simon Patrick, The Parable of the Pilgrim (1664), 153) (Griffin 1973, 193).

67–9 take a flight beyond material sense, /…pierce / The flaming limits of the universe: cf. ‘N’est-ce pas l’Homme enfin, dont l’art audacieux / Dans le tour d’un compass a mesuré les Cieux, / Dont la vaste science embrassant toutes choses, / A foüillé la nature, en a percé les causes’ (Isn’t it Man, whose reckless art, boxing the compass, has surveyed the heavens, whose learning without limits has explored Nature and penetrated into her first causes) (Boileau, Satire VIII, 165–8) (Rochester 1982, 108); flaming limits of the universe: cf. ‘flammantia moenia mundi’ (the flaming outworks of the world) (Lucretius, De rerum natura, I 73) (Rochester 1926, 356). The irony of having the clerical adversary quote ‘the pagan and atheistic Lucretius’ has not been lost (Griffin 1973, 192).

71 true grounds of hope: cf. ‘That Immortality which lay hid in the dark guesses of Humanity, is here [in the Bible] brought to light, and all doubts concerning the Portion of Good men are resolved’ (Nathaniel Ingelo, Bentivolio and Urania (1660), 214).

72–97 The speaker turns the tables on the adversary by arguing that it is not wit but ‘glorious man’ (I. 60) and ‘shining reason’ (I. 64) that is at fault (David Trotter, in Treglown 1982, 130).

73 Ingelo: Nathaniel Ingelo’s Bentivolio and Urania (1660) is a prose romance in four books. There is no pricking on the plain, however, for Bentivolio (Good Will) and Urania (Heavenly Light) are brother and sister. Included in the work is both an Utopia, Theoprepia (The Divine State), and a dystopia, Polistherion (City of the Beasts). In the former, the topics of casual conversation include ‘The Prudence and Fidelity of Vigilant Magistrates, the chearful Submissions of Loyall Subjects, the wise Deportment of Loving Husbands, the modest Observance of Obedient Wives, the indulgent Affections of Carefull Parents, the ingenuous Gratitude of Dutifull Children, the discreet Commands of Gentle Masters, and the ready Performances of Willing Servants’ (234).