VIDEO GAMES ARE NOT A REVOLUTION in art history, but an evolution. Whether you are drawing on paper, canvas, or a computer screen, the medium on which you draw is always an inanimate, flat surface that challenges you to make something without depth feel like a window onto a living, breathing world.

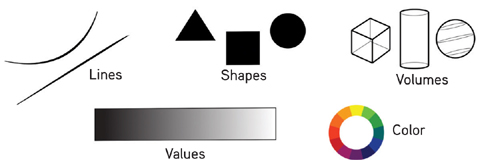

The technology powering today’s games influences the way we experience visual art in a new way—with the gentle push of a player’s thumb we can now interact with these visual worlds. But take away that interaction and what remains is the static visual artwork itself. And the success of that artwork relies on the same visual grammar (lines, shapes, volumes, value, color) and classical art techniques that have evolved over two thousand years.

The focus of this book is how far we can push the world of game art in purely visual terms without relying on the technology of interaction, that is, on sound, special effects, and animation. By going back to square one and studying the basic elements and significance of visual grammar and technique, you will discover how visual grammar can be artistically shaped to create a range of emotional experiences using classical theory of depth, composition, gravity, movement, and artistic anatomy. (That’s why distinguished video games like BioShock, Journey, ICO, and Portal 2 are featured alongside the work of Old Masters such as Michelangelo, Tintoretto, and Rubens in all the drawing exercises throughout the book.) Later in the book these essential skills are applied to game art creation, providing you with reliable processes for creativity and imagination, character development, environment design, and color. I’ll also show you how to put together a professional portfolio to help you secure work in game development.

Viewed from an angle, the similarities between drawing, painting, and game imagery become more apparent, as the illusion of life and depth in each artwork is created on a two-dimensional, static surface. Without the benefits of digital animation and interaction, the challenge of creating a window into a make-believe world is the same for video game artists as it was for the Old Masters.

Study of the Laocoön Group (1601) by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

The Laocoön Group sculpture was created sometime around 25 BC, more than sixteen hundred years before Rubens made this study. Rubens and other master artists like Michelangelo and Tintoretto continued to make studies of ancient Greco-Roman sculptures throughout their careers.

There are a significant number of techniques to master in this book. Although each is fairly simple, the drawing process becomes significantly more difficult when managing several techniques simultaneously while rendering complex subjects, such as human figures. Discipline through repeated practice is required to maintain a clear and structured process when drawing.

Ideally, you should practice drawing every day. One of the best ways to practice is to copy artworks of artists you admire. Copying art allows you to absorb the artist’s ideas and experience his or her process and then apply it to your own work. The Old Masters themselves used this technique, refining and perfecting their skills by endlessly copying artworks like the statues of the Greeks and Romans. The lessons in this book are based on this copying concept, and each of the classical and game artworks is a drawing lesson. (The text accompanying the art explains the visual grammar and techniques in the work.) Keep a sketchbook and pencil at hand as you work through this book, making a quick study of each artwork as you read through the chapters. The straightforward quality of the drawing medium will allow you to easily identify skills that need improving and will help you develop a higher level of dexterity and understanding of artistic principles when creating artwork for video games.

Classical artists made their studies and preparatory drawings deliberately small, as a small drawing is easier to manage and quicker to complete. The art in this book is purposely sized to make it easy to copy in your sketchbook without having to scale it down to fit the page.

Whether you’re a student looking for a career in video game development or an industry veteran, this book will give you the tools to be creative on demand and to design video games with a broader range of emotional experiences that affect players in new and meaningful ways.

Let’s get to work!

Group of Figures by Luca Cambiaso (1527–1585)

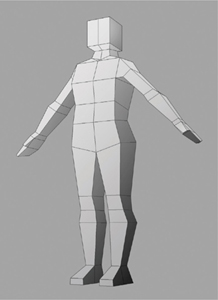

The preparatory sketches of Luca Cambiaso are explicit examples of the conceptual process that classical artists practiced to simplify complex forms. They distilled objects to basic geometric volumes, which gave them the ability to create convincing figures from their imaginations, as you can see in this Cambiaso sketch. This process of visualizing complex forms as basic volumes allowed the Old Masters to freely design compositions and work out complex problems of depth, light, anatomy, proportions, and the illusion of movement. Until details were added, the theme and identities of their figures could go in any number of directions.

Typical 3D character base mesh, by Andi Brandenberger

The classical preparatory stage is mirrored in game development, where every 3D model starts off as a nondescript base mesh. The forms and proportions of the base mesh are shaped to the general design of the final character before subsequent stages of refinement are undertaken. Unlike traditional mediums, the computer automates many of the technical challenges of calculating perspective and light.

Venus and Adonis (1565–69) by Luca Cambiaso

Luca Cambiaso would have likely created his preparatory composition sketches from imagination but relied on models for studying details and for the final stages of painting. Any details he introduced would then overlay the composition and conceptual volumes established in the earlier preparatory stages.

How do we go about creating complex emotions for our characters and game designs? And what exactly is visual grammar? The answer is surprisingly simple: lines, shapes, volumes, value, and color. Each element is deceptively simple but it’s how we manipulate, stretch, combine, contrast, subvert, and animate these elements that creates an infinite number of expressive possibilities. You’ll develop an understanding for the significance of each element through the practice of drawing.

The Prince and Elika in Ubisoft’s Prince of Persia (2008)

After the broader forms of the base mesh are established, artists can go about adding details such as facial features, textures, and animation based on previsualization and research relating to the game’s overall theme.

The surprising thing we’ll discover throughout this book is that it’s the preparatory base mesh stage, not the details, which is primarily responsible for the viewer-player’s emotional experience. Details are merely the fine-tuning of a broader concept.