EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: There are predictable evolutions and revolutions as an organization grows. These are dictated by the increasing complexity that comes with adding employees, customers, product lines, locations, etc. Handling a company’s growth successfully requires three things: an increasing number of capable leaders; a scalable infrastructure; and an effective marketing function. If these factors are missing, you will face barriers to growth. Scaling up successfully requires leaders who possess aptitudes for prediction, delegation, and repetition.

I’m tired of sailing my little boat

Far inside of the harbor bar;

I want to be out where the big ships float —

Out on the deep where the Great Ones are! …

And should my frail craft prove too slight

For storms that sweep those wide seas o’er,

Better go down in the stirring fight

Than drowse to death by the sheltered shore!

— Daisy Rinehart

Back in 1999, Alan Rudy was a disillusioned CEO. “Wasn’t I supposed to be making more money and having more fun, the bigger the company got?” wondered the founder of Express-Med, a mail-order medical supplies firm based in Ohio. “I was angry all of the time,” remembers Rudy. “I had a long weekend planned to go skiing with my father and two brothers for the first time in 10 years, yet I bagged out at the last minute because the business needed me to hold things together.”

To make matters worse, on March 30 of that year, Rudy’s CFO showed him financials that estimated a first-quarter profit of $300,000, yet two days later, his CFO said that they had actually lost $350,000. “For several hours, I thought it was an elaborate April Fools’ joke,” he chuckles today. “I kept trying to be a good sport about it, yet it turned out to be true.” Turmoil among his staffers capped it off. Associates had fistfights in the parking lot, and one employee slashed the tires of another because of something said at work. The endless firefighting meant Rudy was putting in 80-hour workweeks. Needless to say, “stress was a little high,” says Rudy.

Yet within two years, Rudy had reversed the trends, addressing the barriers we’ll outline in this chapter. Utilizing the tools and techniques you’ll learn in this book, he scaled up his 7-year-old firm into a $65 million industry leader. More important, he says, “It was fun again, and we were making money.” Rudy went on to sell the company for $40 million, completing his own entrepreneurial life cycle: start, scale, sell.

Drawing on the lessons he learned in scaling up Express-Med, Rudy launched an investment firm to unlock the growth and profitability of additional companies. Incubating multiple firms amplified the importance of getting the right people into leadership positions. Because Rudy is a driven leader who “can take over a huddle and tell everyone what to do,” he had to make himself “push accountability down,” so everyone at each company had a stake in helping the business to excel.

Besides mastering these leadership and delegation challenges, Rudy learned a crucial lesson from the marketplace: You have to get your strategy right. This is what he calls finding the “ping” in the business. (Imagine the sound of flicking a plastic cup, representing a weak strategy, vs. flicking a fine crystal goblet, indicative of a clear one.) Great execution won’t get you anywhere if your strategy is wrong. Understanding this has paid off handsomely for Rudy at several of his investments, including Perceptionist.

Perceptionist started out as a call center, answering the phones for companies in 60 to 70 different industries. To uncover the Ohio-based firm’s growth potential, Rudy spent three months on the road visiting customers. (CEO Lou Gerstner had the senior managers at IBM do something similar in an initiative code-named “Operation Bear Hug.”) One of Perceptionist’s clients began grousing about paying monthly rates equivalent to about $1 per minute to have calls answered, especially for misdials. Moreover, the customer waxed indignant about the problems of playing phone tag with clients who just wanted to make an appointment. In his frustration, the customer exclaimed to Rudy, “Forget the buck per minute; I’d pay you $25 to take over my calendar and book appointments!”

A light bulb went on. Rudy sold off accounts that needed only answering services (including ours at Gazelles!) and shifted the company’s direction to booking appointments for its clients. While everyone else in the industry was focused on achieving a certain profit per minute, Rudy focused on attaining a targeted profit per booked appointment. This turned around a situation in which Perceptionist had been struggling to compete with overseas rivals with rates equivalent to 50 cents a minute. Focusing on this new metric and a handful of targeted industries — core customers — that needed appointments booked (plumbing, HVAC, and maid service firms) helped the company bring in revenue averaging $5 a minute. This was more than four times the industry average.

In addition, complexity decreased. “Training costs went way down, since our new reps went from needing to learn the language of 60 different industries to [mastering] just a few,” says Rudy. “In the past, we often could not take on a new customer because we did not have trained personnel,” a huge People problem in scaling the business.

Rudy eventually sold his stake in the company back to the original owner, and he says it is now doing well. Meanwhile, he tripled the value of his investment in the firm.

Rudy has achieved some of his greatest successes with firms when following the old adage, “Grow where you’re planted.” In other words, stick to the businesses and markets you know best. For Rudy, this approach shortens the learning curve of entering a new industry, allowing him to better leverage the contacts and knowledge he already has to address the People, Strategy, Execution, and Cash aspects of each new business. (For more on this key point from the founders of Pizza Hut, Boston Chicken, Celestial Seasonings, and California Closets, read this Fortune article by Verne: http://tiny.cc/worth-repeating.)

In Rudy’s case, growing where he was planted meant focusing on the medical supplies and pharmaceutical industries. In 2003, when he bought a minority stake in MemberHealth, a pharmacy benefits management company that helps seniors get discounts on prescription drugs, it was bringing in $7 million in revenue. Rudy helped the 18-person team implement the Rockefeller Habits, coaching MemberHealth’s founder Chuck Hallberg. At Rudy’s suggestion, the company dived into the first habit, holding a daily huddle at 7:30 a.m. to keep everyone focused on execution. Eventually, Rudy took on the role of chairman, while Hallberg remained CEO. The company rocketed to $1.2 billion in revenue by 2006, when the duo sold it to Universal American Financial, a Nasdaq-traded company, for $630 million. It is now a division of CVS — a really big ship.

And Rudy is at it again. In March 2013, he formed Sleep Health Supplies, which took over a failing firm. He’s CEO and majority shareholder of the business, now known as Good Night Medical. Using disciplines like the daily huddle to stay focused on key metrics, his team has achieved double the orders per year and has kept patients for twice as long as most competitors. Building strong, recurring relationships with customers has enabled Rudy to negotiate a cost of goods from manufacturers that is about 30% lower than his rivals’. All told, he estimates that the value of the firm’s customers gives Good Night Medical about a 10x competitive advantage over other players in the field.

As a serial entrepreneur and investor, Rudy has experienced firsthand the importance of getting the right People in place and learning how to delegate; the power of a focused Strategy to reduce complexity and drive industry-leading performance; and the importance of bringing disciplined Execution to all these ventures through habits like the daily huddle. (He’s a big fan, if you haven’t already guessed.) And he’s both invested and made significant Cash — while continuing to learn what is required to make the ride enjoyable along the way.

Like Rudy, who continues to go out beyond the harbor bar, you will find that leading a growth company is one of the more exhilarating things you can do in the world. And eventually sailing among the “big ships” can be an incredibly fulfilling and rewarding opportunity.

Jack Harrington’s Big Boat Experience

Raytheon acquired Virtual Technology Corporation (VTC) in 2006, and within 30 days, Jack Harrington, VTC’s co-founder and CEO, was asked to run a $750 million, 2,000-person Raytheon division specializing in command, control, communications, computers, and intelligence (or C4I, in defense industry terms). Admittedly, this was a daunting move for the growth-oriented CEO, who was used to running the much smaller $30 million company. “I immediately called Verne and said, ‘Holy cow, Batman, I’ve got a $750 million business,’” he recalls. “He told me that I had all the skills and talent I needed and that I could do it. And in my heart, I wanted to see if I could take what I learned in growing a fast, entrepreneurial company and apply it to a larger business. I immediately brought in the Rockefeller Habits, starting with the morning huddles, and then quarterly strategic planning meetings using the One-Page Strategic Plan. It was really incredible to increase our alignment, strategic thinking, and debate.”

Harrington was next asked to lead an even larger organization, ThalesRaytheonSystems, a joint venture equally owned by Raytheon Company and France-based Thales S.A. He notes that the same habits and meeting rhythms were responsible for creating a more collaborative culture across the French and American operations. Plus, the organization became much more aligned around the strategic vision of the company. What was once a divide-and-conquer approach to managing the business changed dramatically. “Everyone is building trust and relationships,” he says. “It’s tremendous, because you’re not just getting together to discuss operations. You’re discussing strategy and debating the market, and that really brings out incredible insight and power.”

Yet for many business leaders, scaling the business is a nightmare. Does every employee you hire, every customer you acquire, and every expansion you drive actually make you tired? Are you working longer hours, although you’d thought there should be some economies of scale as the business grew? Does it feel like everyone is just piling onto an increasingly heavier anchor that you alone are dragging through the sand? This isn’t what you signed up for. It’s supposed to get easier as you scale, so what happened?

You’re experiencing the growth paradox: the belief that as you scale the company — and increase your dream team, prospects, and resources — things should get easier, but they don’t. Things actually get harder and more complicated.

Yet Harrington’s experience in scaling VTC to $30 million and leading a growing 2,000-person division at Raytheon demonstrates that the techniques you’re learning in this book do scale — and that they are as applicable to some of the largest companies around the globe as they are to growth firms.

So why do only a fraction of companies actually scale up, while others fail to scale? How do you counter the growth paradox? What did Harrington have to master at VTC that was transferable to his Raytheon experience?

In short, he had to conquer complexity (and so do you!).

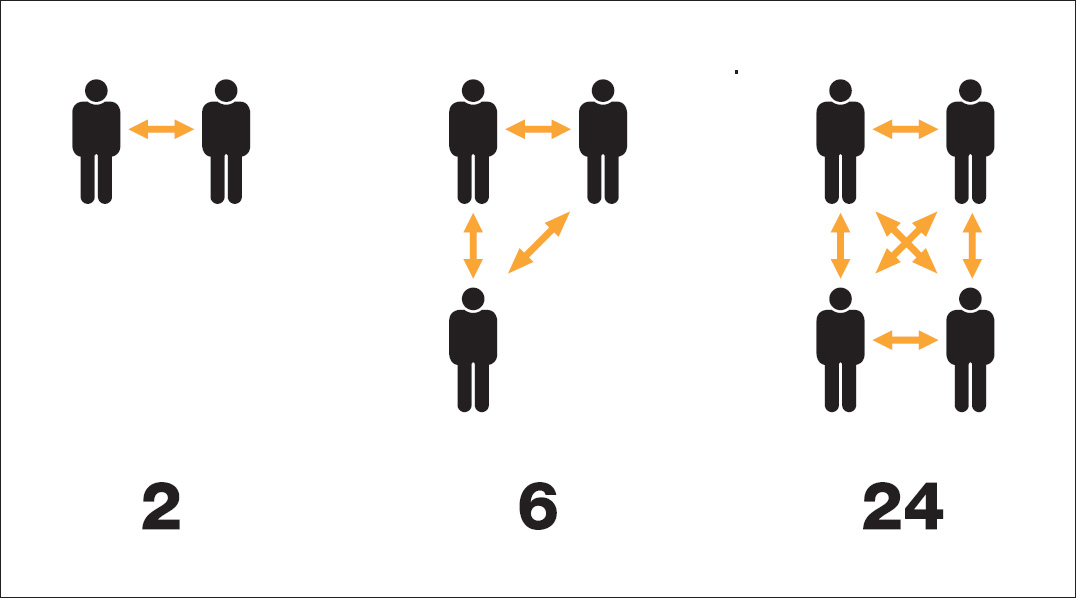

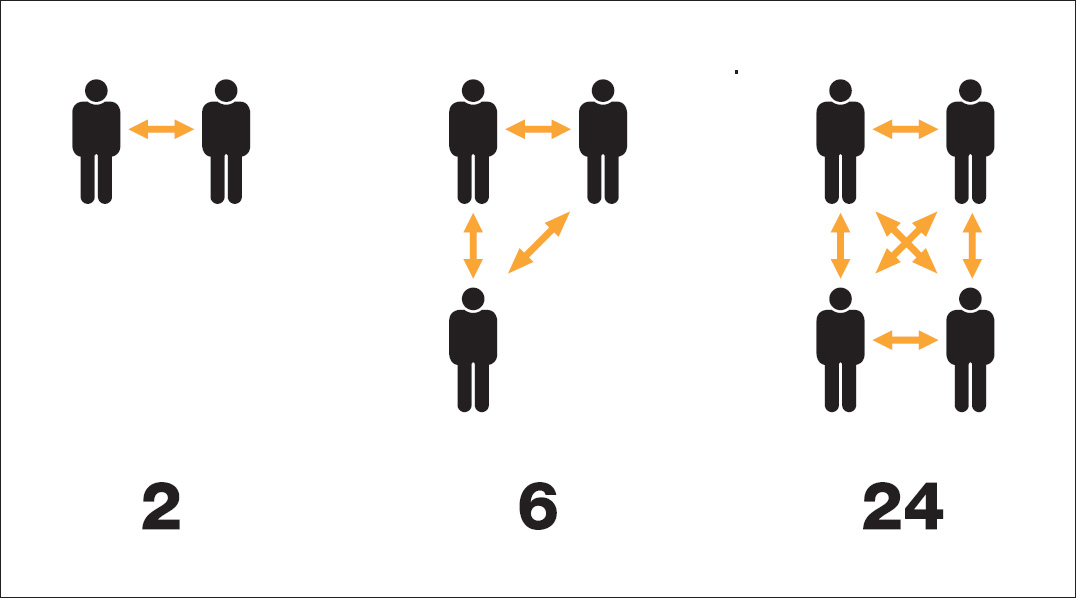

Think back to when your company was just the founder and an assistant with a plan on the back of a napkin. This start-up situation represents two channels of communication (degrees of complexity), and anyone in a relationship knows that is hard enough. Add a third person (or customer or location or product), and the degree of complexity triples from two to six. Add a fourth, and it quadruples to 24.

Expanding from three to four people grows the team only 33%, yet complexity may increase 400%. And the complexity just keeps growing exponentially. It’s why many business owners often long for the day when the company was just them and an assistant selling a single service.

This complexity generates three fundamental barriers to scaling up a venture:

• Leadership: the inability to staff/grow enough leaders throughout the organization who have the capabilities to delegate and predict

• Scalable infrastructure: the lack of systems and structures (physical and organizational) to handle the complexities in communication and decisions that come with growth

• Marketing: the failure to scaleup an effective marketing function to both attract new relationships (customers, talent, etc.) to the business and address the increased competitive pressures (and eroded margins) as you scale

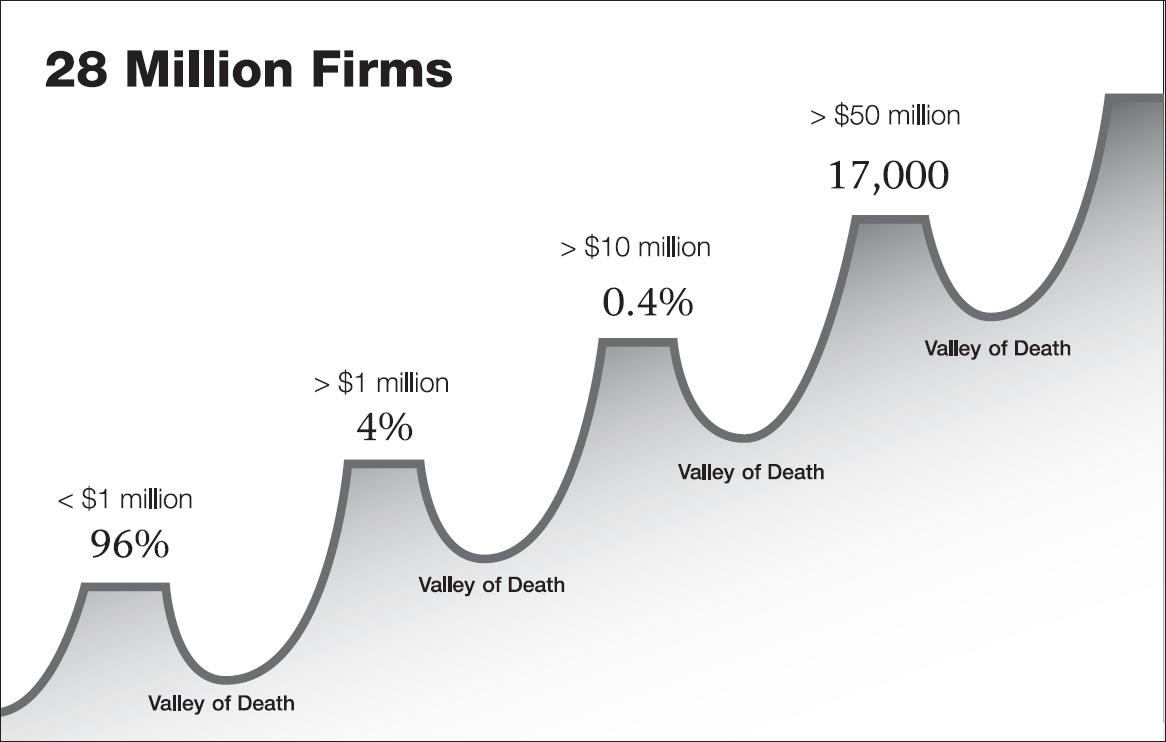

When you remove these barriers, then that anchor you’ve been dragging turns into wind at your back. You can get your boat sailing ever faster. You can better navigate through the “Valleys of Death” — those points in the company’s growth where you’re bigger, but not quite big enough to have the next level of talent and systems needed to scale the venture. These are points where the business needs to leap from one whitecap to the next or risk falling into an abyss (see figure).

There are roughly 28 million firms in the US, of which only 4% ever reach more than $1 million in revenue. Of those firms, only about one out of 10, or 0.4% of all companies, ever make it to $10 million in revenue, and only 17,000 companies surpass $50 million. Finishing out the list, the top 2,500 firms in the US are larger than $500 million, and the top 500 public and private firms exceed $5 billion. Data indicate that there are similar ratios in other countries.

What defines the hills and valleys is related more to the number of employees than to revenue, since this is what drives the complexity equation mentioned above. If you figure roughly $100,000 revenue/employee for small firms and $250,000 revenue/employee for larger firms (yes, larger firms are more efficient on average); and you figure that one can lead seven to 10 others, you get some natural clusters:

• One to three employees (the majority of home-based businesses)

• Eight to 12 employees (a very efficient company with a leader and a bunch of helpers)

• 40 to 70 employees (a senior team of five to seven people, leading teams of seven to 10 — in a company where you still know everyone’s name)

• 350 to 500 employees (seven leaders, with seven middle managers each, running teams of seven to 10 — actually a very efficient company)

• 2,500 to 3,500 employees (more multiples of seven to 10)

Any company with an employee count between these natural clusters is likely feeling a bit stuck. Everything seems to take longer to complete. Problems you thought you had solved earlier start creeping up again. And you’re feeling this “big, but not big enough” syndrome — even in making minor decisions like what size photocopy machine you need next.

As an organization follows this growth path, it goes through a predictable series of evolutions and revolutions. For more on these natural cycles, read professor Larry E. Greiner’s classic Harvard Business Review article titled “Evolution and Revolution as Organizations Grow,” from July-August 1972 (updated in May 1998).

Scott Tannas and His Valleys of Death

In 2011, Western Financial Group (WFG) — an Alberta-based financial services company with more than 2,000 employees — was acquired by Quebec-based Desjardins Group in a $440 million transaction. In the 15 years between WFG’s IPO in 1996 and its return to being privately owned, the company’s stock price rose 1,038%. Founder and Vice Chairman Scott Tannas remains committed to growing the company, and regularly shares with other entrepreneurs his insights on how to handle growth. “Verne talks about the Valleys of Death in how companies grow, and for those of us who have grown a big business, it’s true,” he says.

Drawing from his own experience scaling WFG during 20 years as CEO, Tannas shares that when a company grows from two to 10 employees, it arrives at a “Valley of Death” because processes have to change. You’ll need to hire an assistant manager. “You can’t run the business all by yourself, so you need to change the way you run it, and some guys can’t get over it,” says Tannas. After 25 employees, you face another set of challenges. For example, you need to hire someone to control money. At around 100 employees, “you need internal communications processes because you can’t have a single staff meeting anymore,” Tannas says. Company politics also come into play. “You have employees who think they know more than others,” he notes. “All these different challenges come at different stages of growth that require you to change things. If you don’t, then you will either fall backward or you’re doomed to stay a company of that size.”

Hoping to tap into some of his business experience to grow the economy of his own country, Tannas became a senator in the Parliament of Canada in 2013.

The three barriers to leadership, infrastructure, and marketing that can prevent firms from dealing with complexity are obstacles that Rudy, Harrington, and Tannas negotiated when growing their companies. Let’s examine each barrier in more detail.

As goes the leadership team, so goes the rest of the company. Whatever challenges exist within the organization can be traced to the cohesion of the executive team and its capabilities in prediction, delegation, and repetition.

Leaders don’t have to be years ahead, just minutes ahead of the market, the competition, and those they lead. The key is frequent interaction with customers, competitors, and employees.

This is much easier when the company is small and the leadership team (or lonely entrepreneur) is personally handling all the sales, programming the software, and delivering the company’s products and services directly. This becomes increasingly more difficult as the business scales up. Senior leaders become further isolated from customers and frontline employees, losing their gut feel for the business and the marketplace.

This is why Rudy spent three months on the road visiting Perceptionist’s customers, discovering a new business model that tripled the value of his investment. In “The Data” chapter, we’ll delineate specific routines, along with tips on harnessing the power of big data, to help leaders improve their ability to “see around corners” in the marketplace. Ultimately, our tools and techniques will free the senior team so they can spend 80% of the week engaged in market-facing activities.

Letting go and trusting others to do things well is one of the more challenging aspects of being a leader of a growing organization.

Most entrepreneurs prefer to operate alone. This is why most companies have just a handful of employees. We often exclaim (tongue in cheek) that many business owners would love their companies even more if they didn’t have to deal with employees or customers! It’s the idea — the dream — of their business that they love the most.

To get to 10 employees, founders must delegate activities in which they are weak. To get to 50 employees, they have to delegate functions in which they are strong! In many cases, the strength of the top leader becomes the weakness of the organization. For example, if the founder is the CEO and the main sales driver, either everyone ignores the big picture or revenue stalls. The leader needs to delegate one of these two functions if the company is to continue to scale up.

From 50 employees on up, the senior leaders must develop additional leaders throughout the organization who share the same values, passion, and knowledge of the business. This way they have enough talent to whom they can delegate the myriad number of activities and transactions necessary to grow the business.

Most MBA programs don’t offer a single course or even a lecture on how to delegate, yet it is one of the most important skills a leader must develop. And many leaders confuse delegation with abdication. Abdication is blindly handing over a task to someone with no formal feedback mechanism. This is OK if it is not mission-critical, but all systems need a feedback loop, or they eventually drift out of control.

Successful delegation requires four components, assuming you have delegated a job to the right person or team:

1. Pinpoint what the person or team needs to accomplish (Priorities — One-Page Strategic Plan).

2. Create a measurement system for monitoring progress (Data — qualitative and quantitative key performance indicators).

3. Provide feedback to the team or person (Meeting Rhythm).

4. Give appropriately timed recognition and reward (because we’re dealing with people, not machines).

The Rockefeller Habits provide the methodologies for leaders to delegate properly.

NOTE: Beehives have only one leader. So why do companies need more? Some firms are experimenting with “bossless” organizations. In these companies, essentially everyone is a leader, able to act on his or her own. This requires a tremendous amount of training and development so all employees share the same DNA (values, purpose, knowledge, etc.) as the CEO. These “agile scaleups” (our preferred term) must also have technology-driven systems in place to handle several of the delegation activities listed earlier. Our favorite book on the topic is Steven Johnson’s Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software. The Rockefeller Habits, when fully implemented (and automated through technology), facilitate the decentralization of organizations, providing pheromone-like communication and feedback trails similar to those that guide the activities of ants and other communities without bosses.

WARNING: Since computing technology has yet to reach the capability of “HAL” in 2001: A Space Odyssey (though it’s getting closer), organizations that attempt the bossless experiment find they still need quasi-team leaders they call “champions” or some other related term. In reality, we still need these middle-management layers, for now.

The leader’s final job is “to keep the main thing the main thing” — to keep the organization on message and everyone heading in the same direction. L. David Marquet, author of Turn the Ship Around!: A True Story of Turning Followers into Leaders, led the US Navy’s worst nuclear sub to first place in a year (without throwing anyone off the sub!). He had a picture hanging on the back of his stateroom door showing a man repeatedly asking his dog to sit, until the dog sits and the man exclaims, “Good dog!” This was a continual reminder to pick a message and then repeat it a lot until the organization responded.

Repetition encompasses consistency. Finish what you start. Mean what you say. And don’t say one thing and do something else. Consistency is an important aspect of repetition.

We’ll reinforce the power of repetition throughout the book. Specifically, we will look at:

1. Core Values: the handful of rules defining the culture, which are reinforced through your People (HR) systems on a daily basis

2. Core Purpose: the top leader’s regular stump speech to keep everyone’s heart engaged in the business

3. Big Hairy Audacious Goal (BHAG®): the 10- to 25-year goal that provides constant context for all of the decisions made throughout the organization

4. Priorities/Themes: a handful of three- to five-year, one-year, and quarterly priorities, which require repeated review on a daily and weekly basis to keep them top-of-mind

A key function of leadership is delivering frequent messaging and metrics to reinforce these key attributes of the company and culture.

As an organization grows, it becomes more complex. It’s a force of nature. The lowly amoeba can do everything it needs with one cell. (The home-based business is similar.) However, as the number of cells increases, the organism begins to develop subsystems — for feeding, elimination, circulation, procreation, etc. In order to survive, each cell must be located close enough to a nutritional source and have sufficient surface area to absorb energy and eliminate waste. That’s why a cell can get only so big.

The same is true for companies, only these subsystems (cells) represent the various functions, locations, and business units within the organization (organism). As these subsystems grow, they must continue to segment, or they become too big and insular and thus experience the problems we see with large bureaucracies. Just as living cells need to be near nutrients, companies need to be close to customers (in terms of locations, product groups, and customer segments). This drives how companies structure their organizations and establish accountabilities.

To keep things flowing, an organization needs a scalable infrastructure (similar to the blood supply and the nervous system). When you go from two employees to 10, you need better phone systems and more structured space. When your company reaches 50 employees, you still need space and phones, and you suddenly also require an accounting system that shows more precisely which projects, customers, or products are actually making money. Between 50 and 350 employees, your information-technology systems need to be upgraded and integrated. And above that, you must revamp them again, as the organization attempts to tie all systems into one comprehensive database. Otherwise, a simple change of address by a customer can unleash a series of expensive mistakes.

NOTE: Don’t decide the physical location of employees and teams haphazardly. Certain functions are best co-located together, which we’ll discuss in the “People” section of the book. Even determining the location of restrooms, break rooms, and meeting rooms is important, especially when a company grows to occupy a second floor or more in a building. Serious communication issues surface when employees on different floors no longer bump into each other. The goal is to increase the cross-interaction (accidental collisions) of various individuals and functions.

The #1 functional barrier to scaling up is the lack of an effecting marketing department, separate from sales (accounting is the second — discussed in the Cash Section). Marketing is critical to both attracting new relationships (customers, talent, advisors, investors, etc.) to the business and addressing the increased competitive pressures (and eroded margins) as you scale. To prevent margin erosion, marketing’s role (with lots customer input) is to determine the right what we should be selling to the best who’s; and how best we should sell at the right price. And because marketing strategy equals strategy, the head of the organization is usually intimately involved in these decisions.

It’s Regis McKenna, author of the classic Relationship Marketing: Successful Strategies for The Age of the Customer, who taught Steve Jobs, Andy Grove, and most of the Silicon Valley tech stars how to market in the 80’s. It was McKenna and his firm that also guided Verne as he built his early global entrepreneurship organizations. McKenna’s focus was twofold. First, the key to effective marketing is setting aside one hour per week to focus on marketing i.e. establish a marketing meeting (do you have one?). Second, to make a list of the top 25 (or 250 if you are a bigger firm) influencers — relationships — you need to get behind the venture to scale it up. Then spend time each week figuring out how to network your way to these people. With a compelling vision (elevator pitch), then convince these influencers to help.

The more influential the names you put on the piece of paper, the more potential you have to scale the business bigger and faster. Being young and dumb, as a student at Wichita State University (go Shockers!), Verne boldly included President Ronald Reagan, Steve Jobs, Michael Dell, and the owners of Venture and Inc. magazines on his list of 25. What’s crazy, in just 36 months of working the list, one hour per week, the Association of Collegiate Entrepreneurs (ACE) became a global “overnight” success, hosting a major event in Los Angeles for over 1100 entrepreneurs including Jobs and Dell with full page ads for the organization donated by Venture and Inc. magazines — and a congratulatory telegram from President Reagan. So the first step is to stop and make your list!

The other major agenda item for the weekly marketing meeting is Dr. Philip Kotler’s 4Ps of marketing — Product, Price, Place, and Promotion. Of the four, pricing tends to get the least attention yet is one of the most important decisions you’ll make. Whereas we’ll spend hours working on the cost side of the business; the pricing side is lucky to get an educated guess. To up your skills in this area we strongly recommend reading pricing guru Hermann Simon’s book Confessions of a Pricing Man: How Pricing Affects Everything. His firm Simon-Kucher & Partners is the leading pricing consultancy in the world — you might consider engaging them.

We also encourage you to search for Olgivy’s 4Es of Marketing. One of the largest ad agencies in the world, they have updated the 4Ps of marketing and have provided a complimentary online presentation and whitepaper on the 4Es — Experience, Exchange, Everyplace, and Evangelism. Spend time each week working on how to execute better the 4Es of the business.

Last, we encourage you to read Adele Revella’s book Buyer Personas: How to Gain Insight into your Customer’s Expectations, Align your Marketing Strategies, and Win More Business. Ultimately, marketing’s job is to identify and attract the best (right) customers to the venture and arm the sales team (or those driving your online marketing activities) with a definitive list of prospects and plenty of information to help them make the sale. If not, sales teams (distributors) will chase any low hanging fruit they can find which is the quickest way to defocus the business and crush your margins.

More broadly, the marketplace makes you look either smart or dumb. When it’s going your way, it covers up a lot of mistakes. When fortunes reverse, all your weaknesses seem to be exposed. Bill Gross, founder of IdeaLab which has launched over 100 companies, looked at the key factors to the success of growing firms — including people (team), strategy (business model and idea), and cash (funding). What he determined is that market timing trumped them all. Too early or too late with your great idea and you miss the wave.

There’s an additional cruel and counterintuitive market dynamic when you’re growing a business. As the firm scales from $1 million to $10 million in revenue, the senior team tends to be focused externally on amassing new business. Yet this is precisely the time when a little more internal focus, to establish healthy organizational habits and a scalable infrastructure, would pay off in the long term. As the business scales past $10 million, organizational complexities tend to draw the attention of the senior team inward (leading to firefighting). This is precisely when the team needs to be focused more externally on the marketplace (by talking to customers, as Rudy does), given the increased competitive pressures that come with size.

There is also an important sequence of focus when it comes to your financial metrics. Between startup and the first million or two in revenue, the key driver is revenue (sell like hell). The focus is on proving that a market exists for your services. As for cash, which many business owners might think is the first focus, the entrepreneur has to rely mainly on family and friends (or fools!).

It’s between $1 million and $10 million that the team needs to focus on cash. Growth sucks cash, and since this is the first time the company will make a tenfold jump in size, the demands for cash will soar. In addition, at this stage of organizational development, the company is still trying to figure out its unique position in the marketplace, and these experiments (or mistakes) can be costly. This is when the cash model of the business needs to be worked out (e.g., “How is the business model going to generate sufficient cash for the company to keep growing?”). Will the business model generate its own cash internally; have sufficient lines of credit to sustain growth; and attract investors with deep-enough pockets to support it?

As the organization passes $10 million in revenue, new internal and external pressures come to the forefront. Externally, your organization is on more radar screens, alerting competitors to your threats. Customers are beginning to demand lower prices as they do more business with your company. At the same time, internal complexities increase, which cause costs to rise faster than revenue. All of this begins to squeeze an organization’s gross margin. As gross margin slips a few points, the organization is starved of the extra money it needs in order to invest in infrastructure, like accounting systems and training. This creates a snowball effect of further expensive mistakes as the company passes the $25 million mark.

To prevent the erosion in your margins, it’s critical that you maintain a clear value proposition in the market. At the same time, the company must continually streamline and automate internal processes to reduce costs. Organizations successful at doing both will see their gross margins increase during this stage of growth, giving them the extra cash they need to fund infrastructure, training, marketing, R&D, etc.

By the time it reaches $50 million in revenue, an organization should have enough experience and a strong-enough position in the market to predict profitability accurately. It’s not that profit hasn’t been important all along as the organization grows. It’s just more critical, at this stage, that organizations generate predictable profit, since profit swings of a few percentage points either way represent millions of dollars.

Which brings us full circle to the main function of a business leader: to build a predictable revenue and profit engine in an unpredictable marketplace and world. The “20-Mile March” lesson from Jim Collins and Morten T. Hansen’s book Great by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos, and Luck — Why Some Thrive Despite Them All highlights how companies with steady growth year in and year out dramatically outperform firms that experience wild swings in revenue and profits.

The spoils of victory go to those who maintain a steady pace, day in and day out, in all kinds of weather and storms. And it’s this predictability, driven by effective processes, that is ultimately the key to crafting an organization that attracts and keeps top talent; creates products and services that satisfy customer needs; and generates significant wealth.

In summary, growing a business is a dynamic process as the leadership team navigates the evolutions and revolutions of growth. And like the growth stages of a child, they are predictable and unavoidable. To deal with these challenges, the company must grow the capabilities of the leadership team throughout the organization; install scalable infrastructure to manage the increasing complexities that come with growth; and stay on top of the market dynamics that affect the business.

To do this, there are 4 Decisions that leaders must address: People, Strategy, Execution, and Cash. These are the same four that Rudy and his team continue to face as they scale up their latest venture. The rest of the book is organized around these 4 Decisions, providing you with tools, techniques, and best practices for making the critical judgment calls that drive growth.