EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: “The bottleneck is always at the top of the bottle,” notes management guru Peter Drucker. Challenges within the company normally point to issues with, or among, the leaders. To address them, this chapter will focus on the leadership team. We will share three tools that help leaders get clear on their personal goals; define senior leadership accountabilities, key performance indicators (KPIs), and outcomes; and delineate the four to nine processes that drive the company. We include a short primer on organizational theory to help you think through how to properly divide the company into functions, product/service lines, and divisions.

HINT: Keep everyone as close to his or her respective customers as possible!

Co-founders Stephen Roche and Simon Morrison realized that if they wanted to keep Shine Lawyers growing, they needed to bring up the next generation of leaders to drive the day-to-day so Roche and Morrison could focus on expansion. In addition to promoting Jodie Willey and Lisa Flynn into senior legal management roles, they brought on a new executive team to assist the 600-person law firm, with 30 locations across Australia, in its next stage of growth.

A decision to take the Rockefeller Habits-driven firm public, making it one of the first three law firms in the world to hold an IPO, spurred even more shifts in the organizational chart. Morrison moved to managing director, while Roche remained executive director, focused on fostering the strategic growth of the business through acquisitions and emerging opportunities. They also recruited new board members with key IPO experience.

“We now have a great team of talented young people who will take the business to new heights,” says Morrison.

As a company scales up, the toughest decisions involve people and their changing roles in the organization, especially within the leadership team. Loyalties, egos, and personal friendships make these decisions even more difficult when the company faces a situation in which it has outgrown some of its early leaders.

In this chapter, we’ll explore these senior leadership dynamics of a growing company, and the functions and processes needed to scale up the business. But first, a quick primer on organizational design.

Remember the days when the start-up team was crammed into a single office like clowns squeezed into a Volkswagen? Now the company has 150 employees, or 1,500, and you find it infinitely more difficult to know how to divide up teams and set clear accountabilities. Worse, both customers and employees seem confused about how to navigate your organization.

We can take a clue from nature to solve these problems. Human organisms are made up of billions of cells vs. just a few specialized ones for a good reason: A single cell can only get so big and stay healthy. Once it reaches a certain size, the outer membrane won’t have enough surface area to bring in nutrients and eliminate waste to support the cell. The cell will start to die from the inside out (like big bureaucracies!).

This means that the cell must divide. So, too, must your company or it won’t be able to function in a healthy way. And just as no cell can be too far from the blood supply, no team can be too far removed from the action of the marketplace — or so big that it becomes unwieldy and unresponsive (think of Amazon’s “two-pizza rule” — no team should be so big that it can’t be fed with two pizzas). This is the main principle underpinning effective organizational design. Divide big teams into smaller ones aligned around projects, product lines, customer segments, geographical locations, etc., based on the idea of getting everyone in the organization into small teams and as close to his or her respective customers as possible. This is a way to increase the surface area of the company, giving the maximum number of employees a chance to interact with the marketplace.

Each cell within the organization must have someone clearly accountable for it. This doesn’t mean the person is boss and/or gets to make all the decisions. In fact, it’s important to delineate the differences between accountability, responsibility, and authority.

Though spelled differently, these business terms are often haphazardly interchanged. Here are our definitions:

Accountability: This belongs to the ONE person who has the “ability to count” — who is tracking the progress and giving voice (screaming loudly) when issues arise within a defined task, team, function, or division. It doesn’t mean he or she makes all the decisions (or even any decisions) — which is why people often talk about leaderless teams. However, someone must still be accountable. The rule: If more than one person is accountable, then no one is accountable, and that’s when things fall through the cracks.

Responsibility: This falls to anyone with the “ability to respond” proactively to support the team. It includes all the people who touch a particular process or issue.

Authority: This belongs to the person or team with the final decision-making power.

“If more than one person is accountable, then no one is accountable.”

As an example, Gazelles’ CFO has accountability for cash — she literally “counts” and reports it to the team daily. And she’s accountable for alerting the team if she senses any potential issues now or later in the year. In turn, Verne, as CEO, maintains the authority over cash, signing off on major expenditures and investments. And everyone in the company has responsibility for making sure that cash is spent wisely and that deals/contracts are structured so they help generate vs. absorb cash as Gazelles continues to scale up.

But don’t accountability and authority need to be roughly equal — as in “I need sufficient authority if I’m going to be held accountable?” For frontline staff, yes. At a Ritz-Carlton hotel, where the philosophy is that any employee who receives a complaint from a guest “owns” that complaint (accountability), first-line employees such as desk clerks, bellhops, and housekeepers are empowered (authority) to spend up to $2,000 to handle any customer complaints. Managers can spend up to $5,000 without additional authorization. A full 250 to 300 hours of first-year training make this possible.

As one moves up the organization into more middle and senior management positions, it’s assumed that this balance of accountability and authority holds. However, those who have advanced up the ranks find that they’ve taken on increasingly more accountability for things they have less and less real control over — until they reach the top and find they are liable (often legally) for anything that goes wrong in an organization that is expanding beyond their day-to-day reach. This is why leaders get paid the big bucks — to bridge this ever-increasing gap between accountability and authority, using their skills of communication, persuasion, education, visioning, etc.

Getting accountabilities clear throughout the organization is crucial. To assist, we have three one-page People tools to help you think through your personal relationship goals; assign specific accountabilities for the company’s functions and business units; and delineate the various process accountabilities in your organization. Working through these will help you identify and prioritize the People challenges on which you need to focus next in scaling up the organization.

People often joke that the best moments of owning a boat were the day they bought the boat and the day they sold it.

There are similar punctuation marks in our lives — the day we’re born and the day we pass away. As busy executives, if we’re not careful, we can find that our personal lives end up as neglected as those vessels forever docked in the harbor (or parked in storage!). Thus, we’re big believers in establishing personal priorities and aligning them with your professional goals.

Just as there are 4 Decisions you make to build a thriving company — People, Strategy, Execution, and Cash — there are parallel areas in your personal life — Relationships, Achievements, Rituals, and Wealth. We encourage each leader of a company to complete a One-Page Personal Plan (OPPP). As with all the one-page tools we’ll detail in this book, you can find a three-quarter-sized copy of the OPPP in the section introduction, or download a full-sized copy at scalingup.com.

To complete the OPPP, start by filling in the Name and Date spaces at the top. Next, let’s walk through the four columns of the OPPP.

In the end, what matters most in life are the depth of your relationships with friends and family; and the sheer number of people you’ve helped along the way. These represent true measures of wealth. Financial wealth, then, is seen as a resource for fostering your relationships. For an inspirational story about an entrepreneur who used his wealth to help millions, read Conor O’Clery’s The Billionaire Who Wasn’t: How Chuck Feeney Secretly Made and Gave Away a Fortune (you’ll also pick up some important tips on scaling up a global business).

NOTE: The list of 5Fs located down the left-hand side of the OPPP — Faith, Family, Friends, Fitness, and Finance — is contributed by James Hansberger. He found, through his decades as a wealth advisor, that what mattered most to those near the end of their life were these 5Fs, in the order they are listed. They serve as a gentle reminder as you set priorities in the OPPP.

Starting at the top of column 1, list the key groups of people with whom you want a lasting relationship (10 to 25 years). In business, you have a tremendous opportunity to help your employees and customers — so consider adding them categorically to the list. In your personal life, important relationships include family and friends.

Also list the various communities in which you’re involved. Ted Leonsis, a Greek-American sports team owner, venture capital investor, filmmaker, and philanthropist, is author of The Business of Happiness: 6 Secrets to Extraordinary Success in Life and Work. He notes in his book a strong correlation between happiness and the number of diverse communities in which you are active.

The next step is to look at the groups listed and pick a few key relationships on which to focus your attention for the next 12 months and the next 90 days. Verne took a year to focus on spending more time with his 6-year-old son, Quinn; and one quarter with his sister, who needed support with some health issues.

At the same time, there may be some people in your personal or professional life who are destructive — literally draining the life out of you — and/or distract you from your higher goals. There’s a space on the form where you can note relationships you want to end gracefully.

Many CEOs find that even after reaching critical milestones for growing their company, they still feel they haven’t made a real difference in the world. The achievements section of the OPPP can pave the way to a more meaningful life. Think about the major ways you’d like to make an impact through your work beyond reaching monetary goals — perhaps by mentoring others or setting up a nonprofit organization — and set objectives in these key areas.

In your personal life, you’ll want to think about how you can make a real difference to the key people in your life. For instance, you might aim to have a blissful marriage, instead of just staying married, as many people do. Signing on to facilitate the five-year strategic plan for his children’s school was an achievement Verne enjoyed prioritizing while writing this book.

The key is focusing on short-, medium-, and long-term achievements relative to the people listed in the relationship column. This might include stopping the pursuit of achievements that are taking you away from the relationships that matter most.

Establishing regular routines in your life will help you achieve your larger goals. Examples of rituals might include planning a weekly date night with your spouse and booking some alone time with each child once a week. For distant family members, you might schedule a regular routine of biannual gatherings.

You might also establish rituals with people whose presence in your life supports your bigger goals. Meeting regularly with a workout buddy; spending time with close friends; participating in a business forum of like-minded leaders; and having a peer coach (a friend who holds you accountable each day — a recommendation by über-executive coach Marshall Goldsmith) are some examples.

And just as there are destructive people with whom you need to end your relationship, there might be some bad habits or behaviors you wish to stop — particularly those that have proved harmful to those around you.

Rather than viewing financial wealth as an end in itself (as a wise guru once told Verne, “All assets become liabilities!”), see it as a resource for supporting the rest of your personal plan. Besides determining how much money you want to set aside for retirement, set goals for the amount of money you want to donate to causes and communities that matter to you over the next several years. Decide how much money you need to support activities with your family and friends, investing in experiences in the coming 12 months that create lasting memories. And note any wealth-producing assets or cash-draining liabilities you need to address in the coming months.

“All assets become liabilities!”

Overall, focus on how your wealth will flow through you in the service of others, rather than hoarding it. This seems to attract more wealth — the natural law of reciprocity. Lynne Twist’s insightful book titled The Soul of Money: Transforming Your Relationship With Money and Life expounds upon this idea.

We hope you find the OPPP a useful planning tool for your life. Let’s now turn our focus to the company.

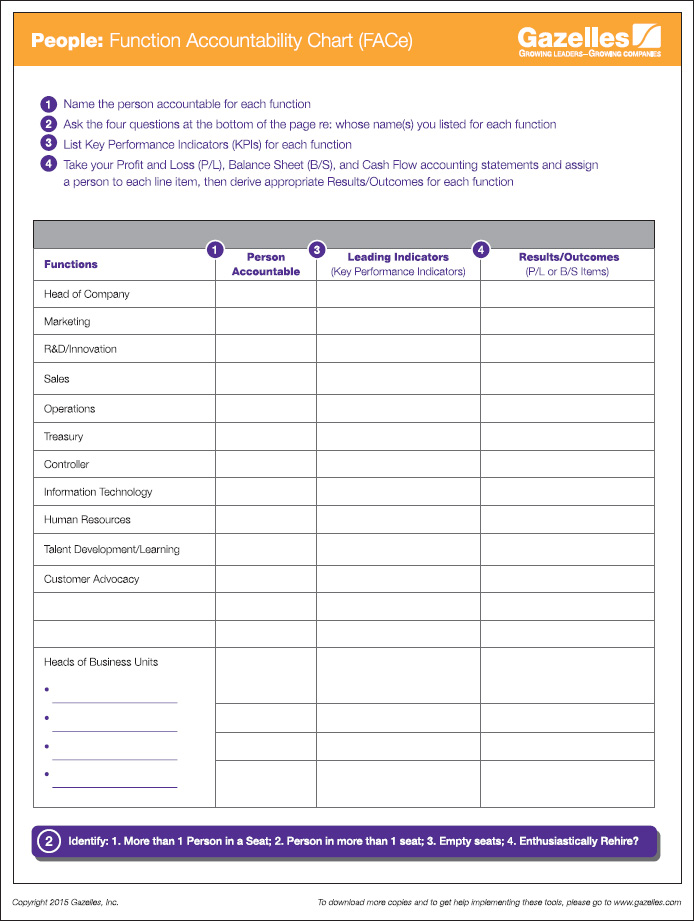

The second one-page People tool — the Function Accountability Chart (FACe) — focuses on making sure you have the right butts in the right seats at the top of the organization (i.e., the “right people doing the right things right”).

An organization is simply an amplifier of what’s happening at the senior level of the company, which is one of the reasons our coaching partners do a quick employee survey as they start working with a business. If the survey reveals that the IT people are upset with marketing, there is likely an issue between those two functional leaders at the top.

The chart lists a common set of functions that must exist in ALL companies. Even start-ups have all these functions, only it’s the founder(s) doing everything! In scaling the business, the idea is to figure out which function on the chart to delegate next.

Like Shine Lawyers’ Morrison and Roche, who continue to promote and recruit new leadership as the business scales, you want to delegate the functions listed on the FACe tool to leaders who pass two tests (including culture fit):

1. They don’t need to be managed.

2. They regularly wow the team with their insights and output.

The chart asks you to list one or two key performance indicators (KPIs) for each function. These KPIs represent the measurable activities each functional leader needs to perform on a day-to-day basis. The last column on the chart captures the outcomes expected for each function (i.e., who is accountable for revenue, gross margin, profit, cash, etc.). These outcomes normally represent line items on the financial statements.

When completed, this one-page accountability tool helps you diagnose where you have people and performance gaps on the leadership team.

As a general rule, you can move people up or over into these functional positions at any time. However, if you need to bring someone in from the outside to fill a senior leadership position, you should do this only once every six to nine months. It takes this length of time to find the right person, get him comfortable in the position, and transfer the DNA of the organization into his psyche. In turn, the new executive will need this amount of time to positively impact the organization enough to pay back his salary.

Now you can afford to bring in another leader. The rule is to take it slow when bringing outsiders into senior leadership roles. The exception is when the company is venture-backed and/or growing 100% a year and needs to bring on three or four key executives within a short period of time.

WARNING: Whatever is the strength of a leader often becomes the weakness of the organization (e.g., if the founder is strong in marketing, the business may eventually find it’s weak in this functional area). Why? Because leaders have a tendency to hold on too tight, strangling the efforts of those around them. Or the leaders figure they can “watch over the details,” bringing in someone too junior to oversee the function vs. bringing on the powerhouse they really need. Instead, leaders must make a counterintuitive decision and find people who exceed their own capabilities in their area of strength, to prevent the company from stalling.

Please read through the following instructions for completing the FACe tool. It often illuminates immediate changes that might need to be made at the top of the organization.

The first column lists the functions every business must support and provides a few blanks so you can add those unique to your business. There is also space to note discrete business units. Notice we don’t list titles (CEO, COO, etc.). The idea is to focus on the jobs that need to get done.

1. Start by having each member of the executive team fill in the first blank column by adding the initials of the person they think is accountable for each function or business unit. It’s acceptable if a function is outsourced (i.e., to an outsourced CFO or marketing consultant). If it’s outsourced to a firm, list the main person accountable from the contracted company.

2. We’ve provided a couple of blank lines for you to add functions that might be unique to your industry or business (for example, a chief technical officer or a quality control person). There is also space to list the names of various business units. For Gazelles, these would include Gazelles International, Gazelles Growth Institute, GazellesPro, and the other divisions we support.

NOTE: When looking at business units farther down the first column, even though you might not have formal business units, you might organize discrete teams around customer groups, product lines, or locations. You can consider these quasi-business units.

3. Compare lists to see if there’s agreement among the members of the leadership team. There often isn’t, even when it comes to who is the head of the company!

Once the team has agreed on the people accountable for each function, consider the four questions summarized at the bottom of the form:

1. Do you have more than one person accountable for a function? The founder might be sharing accountability for sales with another executive, or partners might all be listed next to “head of company.” The rule is that only one person should be accountable; otherwise, there will be confusion. Having more than one name in a box is a red flag.

2. Does someone’s name show up in more boxes than everyone else’s? We recognize that in growth companies, leaders may wear multiple hats, but if one executive’s name shows up three or four times compared to everyone else’s one or two, that leader is either going to die young (a little dramatic) or one of the functions he or she owns will not be supported sufficiently. This is another red flag.

The FACe of Perly Fullerton

When James Perly and Mark Fullerton worked through the Function Accountability Chart (FACe) for their Ontario-based consultancy, Perly Fullerton, a problem immediately jumped out at them: There were six people in the room, but only three names were being put in the boxes. “The problem was that everyone was coming to us for everything,” says Perly. “Even though we hired new people, we just never got rid of any of our senior responsibilities.”

Although it was a long process, now everybody knows exactly who’s accountable, including Perly and Fullerton. “Our roles became really clear in our own minds based on what suits us best for our personalities,” says Perly. “Mark is more of a go-getter with lots of energy, so he’s the chief operating officer because he drives things forward. I take on more of a visionary role [as president], focusing on strategy.”

3. Do you have any boxes with no names in them? This often happens when someone says, “Hey, who’s accountable for marketing?” and the response is, “All of us!” “All of us” really means “none of us,” and the box should be left blank. This doesn’t necessarily require you to hire someone. Let’s take the customer advocacy box as an example. You may have seven or eight people who are overseeing various groups of customers. It’s natural to conclude that this accountability is covered. The rule of accountability means one person must ultimately take ownership, however, so the person to whom these people report has overall accountability. But if that leader isn’t doing anything active to monitor levels of customer delight and follow up, then this function will underperform. Rather than hire an additional person, you might choose one of the customer service reps to hold overall accountability, rotating this role among the reps every six months. Again, this doesn’t mean that any of these people is the boss; it means they are to monitor the situation, ensure that customer-satisfaction feedback is gathered and reported to the leadership team at the weekly meeting, and alert the team if there are issues.

Dell’s Empty Boxes

A company is never so big or sophisticated that it doesn’t sometimes encounter “empty boxes” on its organizational chart. When Michael Dell took back the reins of computer company Dell Inc. in January 2007, he lamented that the chief marketing officer (CMO) position had been empty for two years even though Kevin Rollins had more than 20 executives on the executive leadership team. And indicative of Dell’s customer service problems, there was no one leading the customer advocacy function. So Dell immediately hired Mark Jarvis from Oracle to be the CMO and moved over Dick Hunter from manufacturing to lead the customer service function. That was the beginning of a turnaround and repositioning of Dell that led to Michael taking the company private again in 2013.

4. Are you enthusiastic about the person you have in each box? If the leader isn’t getting the job done, then a change may need to be made. Maybe this leader is in the wrong seat or in too many seats. Maybe there are performance issues. Maybe a person is talented but doesn’t fit the culture (this often happens when a “big company” executive is brought into a growing firm).

ACTION: Discuss these four questions and decide where there are glaring gaps in the leadership team.

WARNING: CEOs often avoid these decisions because they involve executives who have become dear friends. We recognize that this is a touchy subject, but it must be faced if the organization is to grow. One option is for some of the early team members to help launch a new product or division. They are usually more comfortable in a start-up situation or working on a smaller team. And several of the early leaders might be relieved to have the burden of an increasingly important and complex function taken off their shoulders. You won’t know until you have these crucial conversations.

The second blank column is for listing one to three KPIs for each of the listed functions. These are intended to be leading indicators, measuring the daily and weekly activities of a particular leader and meant to drive superior results. For help in selecting KPIs appropriate for your industry and/or function, visit KPILibrary.com. For more general KPIs, we recommend the book Key Performance Indicators: The 75 Measures Every Manager Needs to Know, by Bernard Marr.

WARNING: A common mistake is simply noting down KPIs that are representative of the daily and weekly activities of the person listed for a particular function. It’s critical to zero-base your KPI decisions. Do this by covering up the names listed in the “Person Accountable” column (metaphorically or physically) and then decide on KPIs for each function that align with the business model of the company. Then consider if the person in the job function has the skills and aptitude to deliver on those KPIs. A mismatch might indicate a potential problem.

“Head of Company” KPI

What is the most important KPI for the head of the company? Many might suggest vision, but how do you measure that? Others might suggest more tangible measures, like return on investment or profit, but these are outcomes more suitable for the last column on the FACe tool. Again, the idea of a leading indicator is to measure the specific actions that lead to results. In the case of the head of the company, it’s simply the ratio of all the other boxes on the FACe tool that are right (i.e., the main job of the head of the company is to make sure she has the right people doing the right things right). And when many founders/CEOs realize this, they often bring in someone else to head the company so they can focus on R&D or marketing or customer advocacy. That’s why we emphasize separating titles from functions.

The late W. Edwards Deming, who led the quality revolution around the world, believed that the fundamental job of a leader is prediction. The right KPIs, along with sufficient market intelligence (discussed in “The Data” chapter), help executives navigate what are expected to be turbulent markets throughout the foreseeable future.

ACTION: In the third column of the FACe, note one or two KPIs — leading indicators — for each function and business unit.

For the fourth column of the FACe — “Results/Outcomes” — pull out a recent detailed Profit and Loss (P&L) and Balance Sheet (B/S) statement and assign a person accountable for each line item. Then discuss the same four questions we asked earlier about the people listed for the functions (summarized at the bottom of the FACe tool):

1. Do you have more than one person accountable for any line item (like revenue)?

2. Does someone’s name show up next to more line items than anyone else’s?

3. Do you have a line item with no name next to it (is someone watching telecommunication expense)?

4. Are you enthusiastic about the person you have accountable for each line item?

Again, don’t confuse accountability for authority — recall the earlier cash example within Gazelles. And, as with the functions, spread the workload evenly among the leadership team, with just one person ultimately accountable for each line item.

It was Jack Stack, founder and CEO of SRC Holdings Corporation and author of the classic book The Great Game of Business: The Only Sensible Way to Run a Company, who argued that the Phoenician monks left out a critical column on the first accounting statements they created in the late 1400s: the “Who” column. There should be a person clearly accountable for each line item, even if it’s a middle or lower manager, when considering a highly detailed P&L and B/S.

This exercise has led to some of the most important accountability discussions we’ve ever facilitated in companies. Who is accountable for overall revenue? Who is protecting gross margins from overly zealous pricing concessions? Is anyone watching telecommunications expenses? And for those enamored of formal organizational charts (we’re not — in growing firms, they tend to be outdated by the time they are printed), consider rotating the P&L clockwise 90 degrees and aligning each executive with one of the major line items (CFO owning profit to the left; COO owning gross margin in the middle; VP of sales owning revenue to the right; etc.). Then you have middle managers owning the next layer of line items and frontline managers or employees owning the last detailed line items. Finish by listing the head of the company at the top of this rotated P&L and you have a useful accountability chart from a results standpoint.

ACTION: This is a great exercise for the CFO or person in charge of accounting to lead. Go through your financial statements and decide who is accountable for each line item. Then pick the most important line items for each of the functions listed on your FACe tool and transfer the answers to the “Results/Outcomes” column.

NOTE: Most organizations, at some point in time, develop detailed job descriptions for all the key roles in a company … a huge project. We are not big fans of job descriptions and prefer Topgrading’s Job Scorecards, which you’ll learn about in the next chapter.

Jim Collins, in his book How the Mighty Fall, And Why Some Companies Never Give In, shares a key insight he’s discovered when working with executive teams. When he initially asks them to introduce themselves, he finds that executives with good companies tend to share their titles, whereas executives at strong and great companies share what their accountabilities are in a very measurable fashion, e.g., “I am accountable for driving revenue into this company.”

A concise FACe, with single points of accountability and relevant KPIs and outcomes, aligns with Collins’ insight about the leaders of great companies.

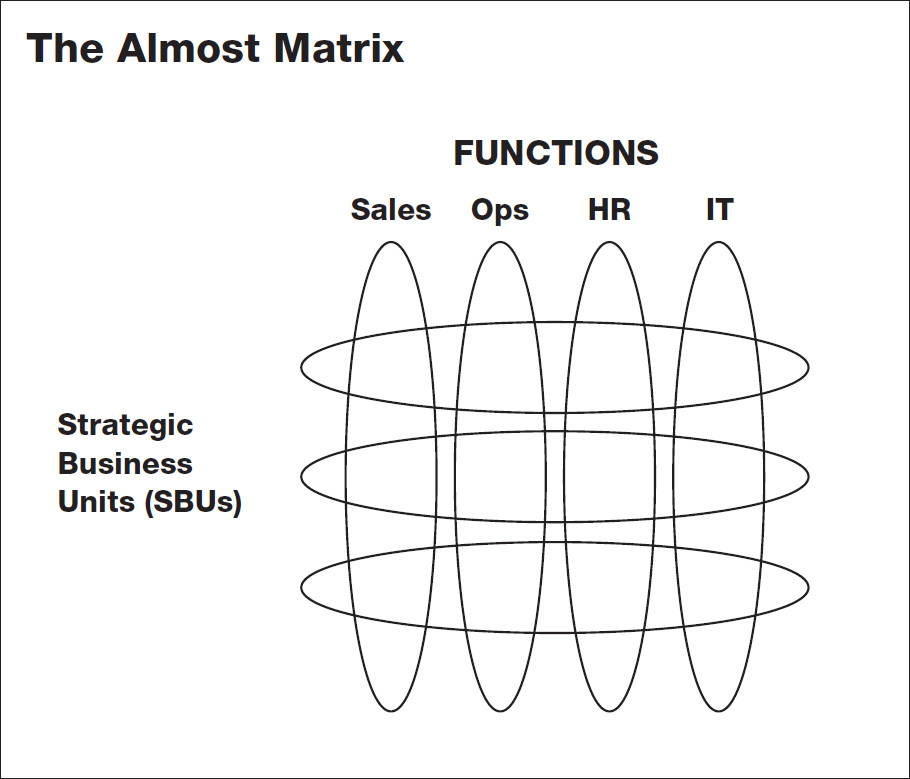

The first natural organizational split is by function. When the business gets above 50 employees, the organization needs to start aligning teams around projects, product groups, industry segments, and geographical regions. This is the beginning of what is commonly called a matrix organization (see diagram).

The pressure to create these new business units usually comes from customers. They complain that they don’t know whom to call to get help. They get the runaround when they finally reach someone. And they feel overwhelmed by the crush of communications that come from multiple business units. Internally, employees may not know from whom they should take direction.

Unless you get accountabilities straight, productivity and innovation will slow, and you’ll waste a lot of time oscillating between centralizing and decentralizing various shared functions among the business units.

To navigate this organizational transition, the functional heads, who have been used to driving the business, need to adapt. They need to become more like coaches/advisors to the business unit leaders, rather than acting as their “bosses.” In turn, the heads of the business units need to lead as if they are individual CEOs. You don’t want weak “yes-people” heading up your business units.

This transition is hardest for the traditional functional leaders — especially for those who were around in the earlier start-up phase. Used to making unilateral decisions, many will have to switch their style from telling to selling as they spend more time outside the organization garnering best practices and then sharing what they’ve learned among the business unit leaders. And respect for the functional leaders’ decisions will have to be earned, not blankly accepted simply because of their position.

Because of these needed transitions, it’s often best to have some of the original functional leaders head business units — maybe head up expansion to a new country or lead the launch of a product line — so they can maintain direct operational control. New functional heads are then recruited who have specific domain expertise (sales, marketing, HR, etc.) and will be more collaborative in working with the business unit leaders.

A matrix organization is also a challenge for employees since they feel like they have multiple bosses. Employees might be serving several business units, in addition to having a functional head overseeing all their activities.

The key is being clear who decides whether an employee gets a raise or a promotion. The mistake is leaving this decision solely to the functional heads. Instead, take the situation where Tom is providing marketing support to several product lines. The functional head of marketing for the company must see his or her role as a trainer/coach to Tom and make it clear that his performance is assessed based on feedback from the heads of the business units Tom serves — and not on what the functional head alone thinks. This way, Tom remains responsive first and foremost to the business units.

Matrix organizations are tricky, and you should seek expert guidance (we can help). Otherwise, companies can waste a lot of time debating about the centralized or decentralized structure, with endless fights over overhead allocations and accountabilities.

Once you have established clear accountabilities, you’ll know very soon if you’ve gotten it right. Customers will be happy, and everyone on your team will be clear on his or her role in serving customers. If you notice patterns of negative feedback from customers — or see internal signs that your “cells” are not healthy — it’s time to revisit the question of organizational structure.

Remember, your company is a living organism that needs to survive in an environment that’s always changing. To thrive, it has to be able to adapt. Charles Darwin found that survival is determined by the ability to adapt to circumstances.

The third one-page People tool — the Process Accountability Chart (PACe) — lists who is accountable for each of the four to nine processes that drive the business and how each process will be measured to guarantee it’s running smoothly.

Example processes include: developing and launching a product; generating leads and closing sales; attracting, hiring, and onboarding new employees; and billing and collecting payments. Almost all these processes cut across the various functions, requiring a coordination of activities that gets more complicated as the organization scales up.

To keep these processes streamlined, we strongly recommend that companies implement the principles of Lean, a management practice invented by Toyota that is as applicable to service businesses as to manufacturing companies. (It’s no accident that Eric Ries called his book The Lean Startup.)

Lean is an approach to process design focused on eliminating time wasted on activities that don’t add value for customers. Using Lean practices, John Stepleton of Research Data Design (RDD) realized a 28% productivity improvement in his call centers within a week; Jeff Booth, co-founder and CEO of Vancouver, Canada-based BuildDirect, was able to dramatically speed up the time it takes to get a vendor up on his building materials website; Mike Jagger saved $60,000 in IT costs from his first Lean session at Provident Security; and Ken Sim, co-founder of the award-winning franchise Nurse Next Door, was able to handle a 100% increase in business in 2008 without adding any headquarters staff.

We are so bullish on Lean that we’re confident that the first company in any industry to fully embrace this methodology will dominate. And for those thinking that Lean is synonymous with the overly complicated and expensive Six Sigma approach to quality improvement, you can relax. Lean, though it requires a real change in mindset, uses a few very simple tools to drive dramatic improvements.

Following are four more detailed examples of how the middle-market company leaders just mentioned applied Lean to their processes. We’ll then follow with specific how-tos for using the PACe one-pager.

Power of Lean

John Stepleton — who built 500-person research company RDD, listed three times on the Inc. 500 — was the first CEO to turn us on to Lean as a powerful tool for middle-market service firms. He applied it so successfully that his former firm was recognized by the Northwest Shingo Prize for its innovative implementation of the Lean principles.

If you’re not sure that Lean is right for your business, Stepleton emphasizes, “I implemented Lean into my call center business, where I had $10/hour employees engaged in continuous improvement programs, that realized productivity improvements of 28% in time periods as short as one week.”

One of the keys to Lean is objectively modeling and measuring productivity and then using simple visual systems to eliminate costly mistakes. In Stepleton’s case, his team color-coded research forms to make sure the appropriate number of subjects was called for each campaign.

Operational Excellence

“One of the things that a company can control in any market is operational excellence by removing waste in a system,” notes Jeff Booth, co-founder and CEO of BuildDirect. In doing so, Booth has dramatically sped up the time it takes to get a new vendor up on his building materials website.

Booth engaged Guy Parsons, early partner with Jim Womack at the Lean Institute, to help him with his initiatives. Booth also produced a five-minute video interview of Parsons as a way to explain to his team and others how they are using Lean. You can visit scalingup.com to view the video.

Eliminating Waste

“Lean describes waste as anything that happens in a company that a customer would not want to pay for,” explains Mike Jagger, CEO of Vancouver, Canada-based Provident Security. “So our first initiative was to divide all of our costs into two columns: things that add value to our clients and things that don’t.

“For instance, we have a huge IT investment that we require for our monitoring business, which adds client value,” continues Jagger. “However, our clients don’t care who hosts our email... so we cancelled our scheduled server upgrade for our exchange servers and migrated the entire company to Gmail.”

First-year savings on hardware, software, management, and support were just under $60,000. “We have another great tool now to help us look at the business in a very different way,” Jagger says, with regard to Lean.

Bored Billing Accountant

Ken Sim sent us a partial list of dramatic outcomes from Nurse Next Door’s first year of implementing Lean, including growing the business by 100% the following year with eight fewer people in the head office. That’s a huge net gain in productivity.

NOTE: Sim emphasizes that there were eight fewer people because of natural attrition. “We will never let go of a person because of Lean,” exclaims Sim. “Otherwise, Lean will die as an initiative. No one is going to implement stuff that will end up costing them their job.”

Case in point: Nurse Next Door’s payroll and billing accountant, Noreen, was working evenings and weekends before implementing Lean. A year later, with twice the payroll, she was accomplishing the job in half the time. When she mentioned in a huddle that she had nothing to do because of her success, the leadership team suggested she take some time off as an example and incentive for everyone else in the office to pursue Lean initiatives. Nurse Next Door is now teaching these Lean techniques to its franchise partners, so they can work on growing their businesses vs. doing payroll all day.

Parsons, like Sim, warns that Lean is not about reducing headcount. It’s about reducing waste. Redirect the time and energy your people get back from eliminating wasted efforts, devoting them to serving customers, making sales, and growing the business.

Nurse Next Door’s additional gains from Lean include doubling the current volume of its call center without adding headcount, while reducing fees to franchise partners; eliminating process steps to ease franchise partners’ work flow and make more money; reducing inventory levels to almost zero so franchise partners require much less capital to start and run their businesses; and streamlining the process for adding new franchise partners.

Adds Sim: “It used to be a challenge to add one new franchise partner each quarter. Now we add two per month and can add up to five per month without breaking a sweat! More important, our Lean initiatives are a major reason (but not the only one) that we and our franchise partners have been able to thrive during a terrible economic period.”

Gather your executive team together (it’s smart to include some middle managers) and name the four to nine key processes driving the business. Several of the processes — like “How do we bill and collect from customers?” — will be similar for most companies. However, there will be a few that are specific to your firm or industry. In our experience, this chart takes a couple of 90-minute sessions to complete. Here are the seven processes for Barcelona-based Softonic, the world’s leading Web portal for downloading free, safe software:

• Recruitment

• Product development

• Sales to cash

• Innovation

• People development

• Customer satisfaction

• Content creation and publication

ACTION: Discuss and agree on the four to nine key processes in your organization.

Next, assign accountability for each process to a specific person. This can be a more difficult decision than initially perceived. Since processes cut across various functions, there might be some turf battles between the functions. In this case, remind everyone that assigning someone accountability for a process doesn’t mean that he is the new boss of everyone who touches the process, nor does he necessarily have increased decision-making authority. His job is to monitor the process (time, cost, quality), let the team know if there are any issues, and lead a regular meeting to fix or improve that particular process. Ideally, this person will have some cross-functional experience.

The person to whom all these process leaders report is usually the head of operations (a COO type). Operations people are generally systems-focused. You want a head of operations who is obsessed with process mapping and improvement — or better yet, experienced in implementing Lean.

ACTION: For each key process you’ve identified, decide who within the organization will be accountable. These people are then accountable to the head of operations.

Identify a few KPIs to track each process. As with the FACe tool, the Process Accountability Chart (PACe) requires that each process have indicators (time, cost, or quality) that will signify its health.

One of the most important KPIs for processes is time — in either number of days (to deliver) or number of hours (to produce). It applies to almost every industry, as customers normally want things better, faster, and cheaper, whether we’re talking about a product or service. Although time is not the only KPI, it does drive efficiency in your business and customer satisfaction and is the key measurement in the Lean process of designing and streamlining processes.

ACTION: List one to three KPIs for each process to measure its speed, quality, and cost.

Following are a few resources that can help you improve the PACe of the organization.

Once you have completed your PACe, gather someone from every function that touches a specific process, including a few customers who are affected by the process (if possible). Using colored Post-it Notes to represent each function (sales is green, accounting is blue, etc.), map out the steps and decision points as the process currently flows. Then step back and begin streamlining the process, eliminating wasteful steps and removing obstacles.

For instance, think about how a certain piece of paper (physical or electronic) moves from a website, to an email inbox, to an order fulfillment desk in the warehouse, including emailed confirmations and order tracking systems for the customer. You’ll be surprised at the number of steps and people required for a simple process.

Along the way, set specific KPIs at critical steps and decision points, so the process can be monitored continuously. The beauty of identifying and documenting the processes in your business is that it provides you with an excellent how-to manual for new employees or existing ones who are off track.

It’s important to revisit and examine one process every 90 days as part of your quarterly planning process. Like hallway closets and garages, these processes get junked up and need to be recleaned periodically. With four to nine processes, each will get examined roughly every 12 to 24 months, which is sufficient to keep your company running drama-free.

ACTION: Assemble the appropriate people for each key process, and list, debate, and decide the steps and decision points for that process.

NOTE: As mentioned earlier in the PACe section of this chapter, we highly recommend using the tools from Lean to both map and improve your processes. Take a look at Paul Akers’ “2 Second Lean” videos on YouTube, including how to set up a “lean desk.”

Once you’ve identified and mapped your processes, you can then bring them to life every day through checklists. Checklists are valuable for key parts of your four to nine processes and help ensure that the right things happen.

In his book The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, Dr. Atul Gawande shares how his research on improving success in surgeries came down to a simple surgery checklist. Among Gawande’s findings: “[Checklists help] with memory recall and clearly set out the minimum necessary steps in a process. … In this one hospital, the checklist had prevented forty-three infections and eight deaths and saved two million dollars in costs. … [Checklists] provide a kind of cognitive net. They catch mental flaws inherent in all of us — flaws of memory and attention and thoroughness. … I have yet to get through a week in surgery without the checklist’s leading us to catch something we would have missed.”

Apple stores draw more people in one single quarter than visit Disney’s four major theme parks in one year. How does Apple do it? One reason is that it is known for delivering fantastic customer service. An article appearing in The Wall Street Journal shared some insight on Apple’s checklist of simple and easy-to-remember steps of service training, the initial letters of which spell out APPLE:

• Approach customers with a personalized warm welcome.

• Probe politely to understand all the customers’ needs.

• Present a solution for the customers to take home.

• Listen for and resolve any issues or concerns.

• End with a fond farewell and an invitation to return.

We’ll discuss the power of checklists more in the “Execution” section of the book. In the meantime, if you’re experiencing some drama, maybe a simple checklist will help.

To conclude, the strength of your People comes from the right leadership doing the right things right (FACe); and the right systems and processes supporting these people to keep the business flowing (PACe). With the combination of the right FACe and the right PACe, you have the key people and process ingredients for a great company.