King Tee (left) and Ice-T are proof that rhyme pays.

IN 1986, LOS ANGELES WAS A CITY UNDER SIEGE.

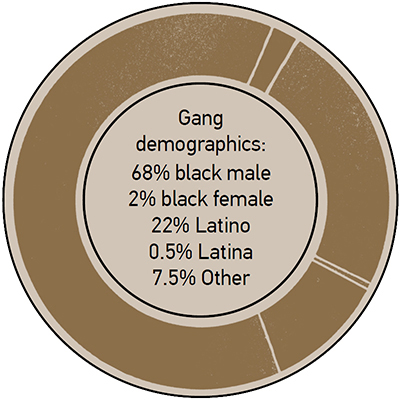

Tens of thousands of reported members of various sets of gangs populated the streets of the Southern California epicenter, notably the Crips and the Bloods. As these notorious factions warred over territory, money, drugs, and women, nearly two hundred gang-related deaths were taking place annually as crack, cocaine, marijuana, alcohol, and firearms flooded the streets.

Against this backdrop, New Jersey transplant Ice-T was emerging as one of Los Angeles’s hottest rappers. As other East Coast rappers were bringing a street persona to their own material, Ice-T had enjoyed international exposure with small roles in the 1984 b-boy movies Breakin’ and Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo. He was also rising through the ranks of Los Angeles’s nascent rap scene, one that was leaning more on disco and electronic influences than the boom bap style of Queens, New York, rap trailblazers Run-DMC.

Early singles such as “Cold Wind-Madness” (produced by Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, later famous for their work with Janet Jackson, among others) and “Ya Don’t Quit” showed Ice-T’s promise as a clever writer, but his friends urged him to write some of the street-based rhymes that he would say to them in private. He decided to humor these requests on the B side of his 1986 single “Dog’n the Wax (Ya Don’t Quit Part II).”

TIMELINE OF RAP

1986

Key Rap Releases

1. Run-D.M.C.’s Raising Hell album

2. Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill album

3. Salt-N-Pepa’s Hot, Cool + Vicious album

US President

Ronald Reagan

Something Else

The Oprah Winfrey Show broadcast nationally for the first time.

But before he released the song, he and his manager, Jorge Hinojosa, put in a series of calls to gangster rap pioneer Schoolly D. They talked to his mother, who served as Schoolly D’s de facto messenger service. Just back from hanging out with the 2 Live Crew in Miami, Schoolly D placed a three A.M. call to Ice-T, who wasn’t available.

“They called me back and were like, ‘Before you say anything, I want to play the song,’” Schoolly D said. “[Ice-T] played me ‘6 ’N the Mornin” over the phone, and I was like, ‘Hell yeah.’ He was like, ‘Respect, because I wouldn’t do this [without your blessing], because if I did it, it would seem like I was biting you, but I’m not biting you. You just inspired me.’ We talked about it, and that was that. That was love. To me, to push the art form forward, I felt like we all had to work together.”

In an August 2015 Twitter exchange, Ice-T reciprocated the respect when he responded to a question wondering why some say Schoolly D is the first gangster rapper.

“I even say that,” Ice-T tweeted. “PSK inspired 6 n the morning. Schoolly was hinting at it. I just said it.”

Schoolly D indeed lit the gangster rap fuse with “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?,” and the genre exploded with the release of Ice-T’s “6 ’N the Mornin’.” Ice-T was inspired by the lyrics and rhyme style of Schoolly D’s work, and he and producer the Unknown DJ drew a portion of their sonic inspiration from the Beastie Boys’ 1986 song “Hold It Now, Hit It.”

An elaborate story rhyme, “6 ’N the Mornin’” ratcheted up the intensity and brazenness of Schoolly D’s material exponentially and took gangster rap from the East Coast streets of Philadelphia to the West Coast streets of Los Angeles.

“It was play-by-play an L.A. day,” Ice-T said.

“It’s like a short film with music, with a score and soundtrack all in one,” adds KK, one half of the Compton rap duo, and DJ Quik protégés, 2nd II None.

Throughout the song’s ten verses, Ice-T unfolds a narrative in which he escapes the police raiding his house, beats a woman with the help of his crew, gets arrested for possession of an Uzi and a hand grenade, stabs a fellow inmate in the eye, gets out after serving a seven-year sentence, starts pimping, is involved in a shoot-out where six people are shot and two die, steals a car, has wild sex, and catches a flight to New York City.

Ice-T called the song “faction.”

“They’re factual situations put into a fictional story,” Ice-T said. “[My friend] Sean E Sean did have a Blazer with a Louis [Vuitton] interior. We did get busted with a hand grenade. All these different things happened at different times, but I made it all happen [in] ‘6 ’N the Mornin’.’ Then I go to jail for seven years. No, I couldn’t possibly have actually gone to jail for seven years. So there’s a lot of fiction and faction put in.”

Listeners were drawn to the song’s realistic elements. “‘6 ’N the Mornin’,’ the shock value on that was so consistent of what we was going through,” says Gangsta D, the other half of 2nd II None. “Before, it was like you keep that under the hush, ’cause you’re trying to get away with something. But, that’s what he gave to the game.”

“They’re factual situations put into a fictional story.”

ICE-T

Ice-T’s lyrically visual style and his genuine street credibility—he was a known hustler—helped propel the genre from the underground rap world to mainstream recognition. His semi-autobiographical storytelling also earned the rapper comparisons to musical and literary legends.

“[T]his reformed criminal is the rap equivalent of pimp-turned-paperback-writer Iceberg Slim,” the Village Voice’s Robert Christgau wrote of Ice-T in 1988.

Born Tracy Marrow, Ice-T came up with his stage name in order to pay homage to Iceberg Slim, the pimp turned author whose 1967 book, Pimp: The Story of My Life, was a poetic and bleak depiction of the world of black pimps that resonated with Ice-T, Ice Cube, and others. There was a vicious, brutal current that ran through Pimp and Slim’s other works, a stark mixture of rawness and reality told in a hypnotic way that captivated readers. Ice-T brought a similarly vivid realism and personal perspective into his presentation of the criminal underworld on “6 ’N the Mornin’,” from pimping and drug dealing to robbery and murder.

But where Iceberg Slim’s cautionary tales resonated largely and most prominently within the black community, Ice-T’s work was appreciated, consumed, and enjoyed by some of music’s most respected white voices as well as droves of young white followers.

Bob Dylan, one of the most celebrated singer-songwriters in music history and a 1988 inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, for instance, said, in Chronicles, Volume One, his 2004 memoir, that he became a fan of Ice-T’s music after being introduced to it by U2 front man, Bono. During the sixties, Dylan’s work on such songs as “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” “Chimes of Freedom,” and “Blowin’ in the Wind” examined the social unrest consuming America marked by the civil rights and antiwar movements.

Just as Bob Dylan served as the soundtrack to his era, Ice-T emerged at the forefront of the burgeoning gangster rap movement with “6 ’N the Mornin’.” Like Dylan, Ice-T was providing a voice to the voiceless and serving as an unofficial spokesman for people pushed to the limits of survival and sanity by America’s government.

Dylan’s material was in line with the progressive thoughts of his era, while Ice-T’s music depicted the aftermath of the civil rights movement. It told the story of the fallout of a generation of kids whose parents marched in the streets of America for equality but whose families and communities were undone by the ravages of the drug epidemic of the early eighties, crack cocaine in particular.

Ice-T was surprised that people wanted to hear music about life on the streets of Los Angeles.

“It was fascinating to me that people liked that,” Ice-T said. “I was like, ‘Yo, people want to hear this gangster shit.’ That’s when my music started to change. I started to go in that direction. It was funny for me. I was like, ‘Oh. That’s what they want? Well, I’ve got tons of that shit.’ It would have been difficult for me to make dance records, or to try to deny who I was, but I just didn’t know that that lifestyle could become a genre of music.”

Gone was the political correctness of yesteryear. “6 ’N the Mornin’” was full of profanity and was presented in an explicit, gritty way, but it wasn’t mindless rage. Yes, the song depicts a life of crime, but in the third verse, Ice-T’s character gets arrested and sent to jail for seven years. In the sixth verse, he explains why he and his crew ran from the police: “Cops [would have] shot us on sight / They wouldn’t [have] took time to ask.”

In “6 ’N the Mornin’,” Ice-T presented a moral overtone, showing that despite some of the glamour and excitement that came with living a life of crime, there were also serious, life-altering—and sometimes life-ending—consequences to being in this world. For the protagonist in Ice-T’s song, it was a seven-year stretch behind bars.

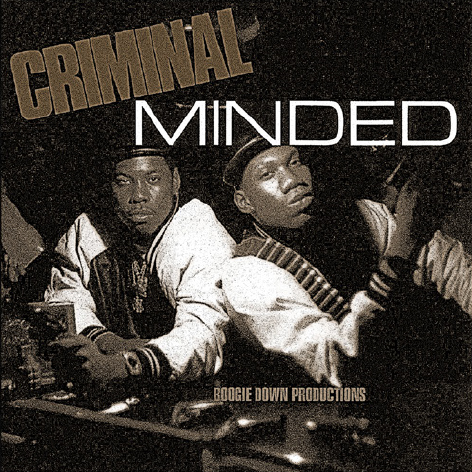

Even with the visual quality of Ice-T’s raps, during this era, outlets for rap videos were virtually nonexistent because MTV (Music Television) had yet to embrace the genre, essentially relegating rap videos to community access programs. Boogie Down Productions, though, brought a visual portrayal of gangsterism to their music. On the cover of their debut album, 1987’s Criminal Minded, Bronx-based group members KRS-One and DJ Scott La Rock posed with pistols, a hand grenade, and a clip of bullets. The cover image matched the gangster raps of Criminal Minded songs “My 9mm Goes Bang” and “Criminal Minded,” which were also released as singles, in 1986 and 1987, respectively.

Formed in 1985, the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) was cofounded by Tipper Gore and aims to limit children’s access to music it considers inappropriate. Material deemed too violent or too sexual, or which contains drug references, is the target of the PMRC. The group, whose influence and significance has waned over the years, originally wanted to initiate a ratings system for albums similar to the one used by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) for films.

More than a dozen record companies agreed to put an advisory sticker on the packaging of their albums, though the initial warning sticker was generic and did not specify the type of content deemed explicit.

Rappers did not take kindly to Gore’s group. Ice-T, for one, blasted the PMRC and Gore on “Freedom of Speech,” a song from his 1989 album, The Iceberg/Freedom of Speech . . . Just Watch What You Say!:

Think I give a fuck about some silly bitch named Gore? / Yo, PMRC, here we go, war / Yo Tip, what’s the matter? You ain’t gettin’ no dick? / You’re bitchin’ about rock ’n’ roll, that’s censorship, dumb bitch / The Constitution says we all got a right to speak / Say what we want, Tip, your argument is weak / Censor records, TV, school books, too / And who decides what’s right to hear, you? / Hey PMRC, you stupid fuckin’ assholes / The sticker on the record is what makes it sell gold

Paris, a San Francisco rapper whose music advocated a Black Panther Party agenda but who was often mislabeled a gangster rapper because of his all-black attire and the violent content of some of his lyrics, agrees with Ice-T that the PMRC actually spurred the sales of raucous rap.

“Anything that was provocative just sold more back in the day,” Paris said. “The idea of censorship and Tipper Gore and the PMRC, all they did was fuel sales because they would censor us or talk about it, but it didn’t bar us from stores. The big difference is that now if people want to censor you, they just ignore you altogether. But back then, if they censored you, there was this kind of fake political type of outrage that occurred that only made each side more emboldened. If you were against what we were talking about, those voices were very loud and very vocal. But to the people who bought our records, that gave us an increased sense of a voice with them. It didn’t hurt anybody, as far as I can tell, who was doing the kind of stuff I was doing, or gangster rap. Our sales just went through the roof.”

More than a decade after Ice-T’s “Freedom of Speech,” Eminem examined the potential societal ramifications of the PMRC’s actions on the outro of his 2002 song “White America,” a cut from his The Eminem Show, which sold more than ten million copies.

To burn the [flag] and replace it with a Parental Advisory sticker / To spit liquor in the faces of this democracy of hypocrisy / Fuck you Ms. Cheney, fuck you Tipper Gore / Fuck you with the freest of speech this Divided States of Embarrassment will allow me to have

The Village Voice’s Robert Christgau bristled at the overt explicitness of Criminal Minded. In his 1988 review of the album he wrote, “KRS-One’s talk of fucking virgins and blowing brains out will never make him my B-boy of the first resort. I could do without the turf war, too.” Yet Christgau also found merit in KRS-One’s work on Boogie Down Productions’ debut album, saying, “[H]is mind is complex and exemplary—he’s sharp and articulate, his idealism more than a gang-code and his confusion profound.”

Given its status as one of the first gangster rap albums, Criminal Minded garnered scant mainstream media coverage. In 2004, though, it earned a perfect five-star rating in Rolling Stone LLC’s The New Rolling Stone Album Guide.

However, in the mideighties, the profanity-laced, violent, and confrontational music of such East Coast street rappers as Schoolly D (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), Boogie Down Productions (Bronx, New York), and Just-Ice (Bronx, New York), who had a 1987 song called “The Original Gangster of Hip Hop,” was largely discounted or ignored by the mainstream media. It was, however, being listened to, studied, and appreciated by a growing number of fans, including future gangster rappers and producers.

“We were inspired by their music,” platinum rapper-producer DJ Quik said. “Our ear was to that shit. When those guys started talking that street shit out there, it was like you had to be from the streets to be able to relate. In a sense, you had to be all-seeing. You had to be hip, in the know. It was just a wave we had where it was like nonverbal communication, like ‘I can relate to that.’ And that’s inspirational, like ‘I want to do a song like that.’ As a young writer, who wishes they didn’t write the last hit song? It was like someone whistled over the gate. You whistle back.”

Gangster rap’s siren song was not limited to the music, though. Schoolly D and Ice-T knew the power of the provocateur and added notes to their early singles calling out that they contained explicit language.

Schoolly D’s and Boogie Down Productions’ popularity as independent acts led them to record deals with Jive Records, distributed through RCA Records, home to multiplatinum R&B singer Billy Ocean and platinum rap act Whodini, while Ice-T’s deal with Sire Records, distributed through Warner Bros. Records, placed him on one of music’s most respected labels.

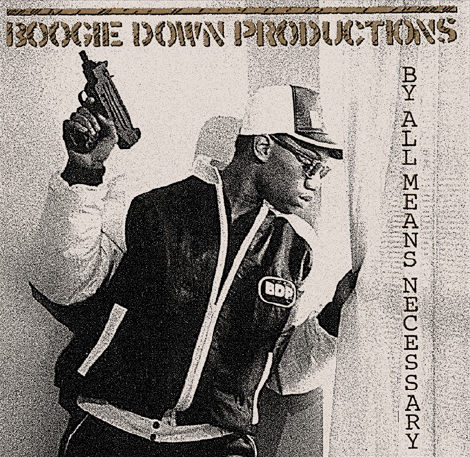

Scott Sterling was working at a homeless shelter in the Bronx in the mideighties when he met Lawrence “Kris” Parker, a homeless teen and aspiring rapper. The two bonded over their love of rap and formed Boogie Down Productions (BDP), with Sterling rechristened as DJ Scott La Rock and Parker going as rapper KRS-One, an acronym for Knowledge Reigns Supreme Over Nearly Everyone. The duo’s 1986 single “My 9mm Goes Bang” featured KRS-One rapping about shooting and killing a drug dealer named Peter and, later, his crew, who came to avenge his death. BDP’s debut album, 1987’s Criminal Minded, featured landmark rap singles “South Bronx” and “The Bridge Is Over,” songs that thrust the group into the rap limelight because of KRS-One’s disses leveled at MC Shan, a popular Queens, New York, rapper whose “The Bridge” single trumpeted the Queens-bridge housing projects he called home. BDP’s brazen gangster rhymes endeared them to fans, but the course of the group was forever changed in August 1987 when Sterling was shot and killed after coming to the aid of BDP affiliate D-Nice, who had gotten into an altercation over a woman. Upon Sterling’s death, Parker changed the direction of BDP’s music from gangster to conscious. He wrote, produced, directed, and mixed the group’s second LP, 1988’s By All Means Necessary. The album is one of the first conscious rap releases.

At the time, Sire Records was enjoying staggering commercial crossover success with Madonna and critical accolades thanks to cutting-edge British rock band Echo & the Bunnymen, Canadian country-pop singer-songwriter k.d. lang, new-wave English musicians Depeche Mode, New York punk rockers the Ramones, and art rock band Talking Heads, among others.

Prior to signing Ice-T, the imprint had never counted a black artist among its roster, let alone a rapper. But the label’s cofounder and Artists and Repertoire (A&R) man, Seymour Stein, a 2005 inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, saw something special in Ice-T. Stein admitted that he didn’t understand Ice-T’s work, but he recognized him being of the same ilk as the other artists he signed. Stein knew from hearing Ice-T talk that he was a musical visionary, so he signed him. Throughout his debut studio album, Rhyme Pays, Ice-T built upon the creative canvas he started with “6 ’N the Mornin’.” With the frantic, mesmerizing “Squeeze the Trigger,” for instance, Ice-T rapped about having an alarming arsenal of firearms, including an Uzi and a twelve-gauge shotgun. But it was his other observations that made the record remarkable and poignant.

Cops hate kids, kids hate cops / Cops kill kids with warning shots / What is crime and what is not? / What is justice? I think I forgot / We buy weapons to keep us strong / Reagan sends guns where they don’t belong / The controversy is thick and the drag is strong / But no matter the lies, we all know who’s wrong

West: Jheri curls, red or blue bandanas, lowriders, Rick Ross, small houses/apartments, 24/7 rap programming, KDAY vs. East: shaved heads, gazelles, train/subway, Larry Davis, projects, mix shows, Kool DJ Red Alert/Mr. Magic

Ice-T’s masterful insight connects the police brutality of the eighties with the Iran-Contra affair that rocked the second term of Ronald Reagan’s presidency. In a scandal that led to the indictment of several government officials, a number of the president’s senior officials secretly facilitated the sale of weapons to Iran, which, at the time, was under an arms embargo. The Reagan administration members wanted to use the arms to secure the release of hostages. At the same time, they wanted funds from the sale of the weapons to Iran to be used to fund the anticommunist Contras movement in Nicaragua, which had been prohibited by Congress.

With his “Squeeze the Trigger” lyrics, Ice-T showed that rappers were paying attention to more than just their blocks. Although locked in their local worlds, they were vitally concerned with global events. Ice-T’s perspective became all the more prescient once it was discovered that at least some of the money sent to Nicaragua was used to fund the explosion of the drug trade in South Los Angeles, of which the CIA was, if nothing else, aware.

The influx of drugs, money, and guns turned mideighties Los Angeles into a war zone. The city’s streets were in such tumult that the police department used modified ex-military tanks armed with battering rams to enter hostile environments, making the juxtaposition of a crack house and a hostage situation all the more powerful. Toddy Tee’s 1985 single “Batterram” bemoaned the use of the vehicle, which destroyed the houses of several families not involved in the drug trade.

On “Squeeze the Trigger,” Ice-T gave America one of its first looks into the specific neighborhoods where both the cops and the gangs inflicted terror on residents. Ice-T took a bold step by naming several of the city’s gangs and a handful of its most dangerous neighborhoods.

From the Rollin’ ’60s to the Nickerson “G” / Pueblos, Grape Street, this is what I see / The Jungle, the ’30s, the VNG / Life in L.A. ain’t no cup of tea

“‘Squeeze the Trigger’ was just a record about me saying that the world’s fucked up and this is what I see,” Ice-T said. “This is what I’m dealing with. I’m not coming from the same place you’re coming from. It was basically my life. These different sets are what I’m dealing with. When I said those on ‘Squeeze the Trigger,’ people had no idea what I was talking about. L.A. people did. Just speaking in L.A. dialect unapologetically was putting gangster rap in motion, just saying things that you knew no one would really understand, but it was so hood.”

That type of street specificity endeared Ice-T to large swaths of Southern California rap fans, allowing him to make inroads that other rappers had not.

“The difference is that Ice was out here with West Coast gangster rap—gangbanging, Crips, Bloods, Eses,” said Hen Gee, a member of Ice-T’s Rhyme Syndicate posse. “They didn’t have that in any other region. Ice was the spokesman that introduced it to the world.”

“Los Angeles artists gravitated more to the reality rap side, and what was going on and the conditions people were living in,” said CJ Mac, who worked extensively with WC and released his 1999 album, Platinum Game, through Mack 10’s Hoo-Bangin’ Records. “That’s what Los Angeles gravitated toward more so than the party, hip-hop rap. So, the streets were more influential in the music because that’s what we thrived on, just trying to make it out. Any story of anybody relating to how you were living is what we wanted to hear.”

“The world’s fucked up and this is what I see. This is what I’m dealing with. I’m not coming from the same place you’re coming from.”

ICE-T

Ice-T put some specific gangs on the national map, but it was clear that his work didn’t glamorize gangbanging. His most damning indictment of the lifestyle on Rhyme Pays arrived on “Pain.” Here, Ice-T opens the song by rapping about a robber who gets incarcerated and laments building his own personal hell.

No matter how cold you roll / You simply cannot win / It’s always fun in the beginning / But it’s pain in the end

In the second verse, Ice-T tells the story of a lifelong criminal who joins a gang and scoffs at the thought of working a nine-to-five but is consumed by thoughts of being incarcerated. These trepidations are eventually overcome, but before the protagonist can move on, he is shot at close range by one of his friends.

The third verse tells the tale of a self-proclaimed “neighborhood terror” who scares his mother as he builds his street empire. But it all comes crashing down when the FBI raids his house, leading to ten criminal charges and an eighteen-year prison sentence.

Although Ice-T was rapping about the criminal lifestyle, he was not endorsing it. Instead, he was presenting the stark consequences associated with that life choice as cautionary tales, like his mentor and namesake Iceberg Slim had.

“My whole angle always was, I’ll be street, but I will always tell you the horrors that go along with this life,” Ice-T said. “That was what I set out to be, unique. I wasn’t just going to document the streets. I’m going to say, ‘Yeah. This looks very glamorous, but you could end up dead.’ Most of my characters I did in my stories would end up dead or shot.”

“That’s part of Ice,” Hen Gee said. “He always wanted to teach. He had more of the vision, the vocabulary.”

As he had done on “6 ’N the Mornin’,” Ice-T also wove explicit sexual adventures into Rhyme Pays. Much like Schoolly D and Too $hort before him, Ice-T boasted of his sexual prowess and the throngs of women at his disposal on such songs as “Somebody Gotta Do It (Pimpin’ Ain’t Easy!!!),” “I Love Ladies,” and “Sex.”

When Stein first heard the early version of Rhyme Pays, he called Ice-T and his manager, Jorge Hinojosa, into a meeting. Stein wanted to voice his concerns. Prior to Rhyme Pays, Stein’s only concerns when releasing an artist’s album were whether or not it was creatively rich and musically vibrant, and whether or not it had commercial potential.

But Ice-T’s album gave him a third concern. Stein was an older, white, Jewish man who was about to position himself as the outlet for black rage. He didn’t question the validity of the record’s content. He did, however, wonder what he was doing. He understood his other artists. Their music had melodies and choruses that he enjoyed and appreciated. They even had instruments. Ice-T’s Rhyme Pays was the antithesis of virtually everything he knew.

As they sat in the A&R department in Warner Bros. Records, Stein explained to Ice-T and Hinojosa that he was surprised by the project’s lyrical content. “Ice went through the record and explained specific lyrics to him that he didn’t understand,” Hinojosa said. “Seymour was very quiet and then Ice said, ‘Maybe that feeling you’re having is money.’ Seymour nodded his head and agreed to release the album.” Rhyme Pays was put on Sire Records’ schedule and Ice-T soon proved that Stein’s move was a prescient one.

Gang members:

150,000 Crips / 25,000 Bloods

Average age:

16

Square miles of gang territory:

28

Colors:

2 (blue and red)

Gang deaths: 398

“What Ya Wanna Do?” DJ Evil E (left) and Ice-T weigh their options.

Ice-T’s Rhyme Pays was released in 1987. It benefitted from Ice-T’s popularity in the streets, his creative reach, and Sire Records’ major label push. Despite earning scant support from radio and video outlets, the album hit No. 26 on the Top R&B/Hip Hop Albums and No. 93 on the Billboard 200 charts and was certified gold with sales in excess of a half million units. With the album selling more than five hundred thousand copies, it was clear that gangster rap was appealing to a wider audience than just the black kids in the hood. It was taking hold in the suburbs with young white fans, too.

The mix of sex and criminality indeed made for an alluring musical concoction, even to some white, mainstream music critics. “[H]is sexploitations and true crime tales are detailed and harrowing enough to convince anybody he was there,” the Village Voice’s Robert Christgau wrote of Rhyme Pays. “Wish I was sure he’ll never go back.” In 1987, rap had shown its sustainability, and more rappers began releasing albums, not just singles. That year, Ice-T’s Rhyme Pays and Just-Ice’s Kool & Deadly (Justisizms) became the first to have warning stickers about explicit content plastered on the covers of the albums themselves.

On the one hand, this tactic was indeed a warning for parents who may have been purchasing the product for their children. On the other hand, it was a sly marketing tool that gave the albums a certain cachet among consumers, especially ones seeking edgy material. These artists were rapping about doing the very things that helped lead to the conditions Melle Mel detailed on “The Message,” and they were proud of it.

What Schoolly D, Ice-T, Boogie Down Productions, Just-Ice, and other artists had started as an independent, underground musical force was growing with an ever-increasing fan base eager to consume this new brand of rap—and with the labels, both big and small, ready to give them a platform.

Yes, the Sugarhill Gang, Kurtis Blow, Whodini, Run-DMC, LL Cool J, Dana Dane, and Beastie Boys had all gone either gold or platinum by 1987, but the rap landscape was changing. The first-person presentation of gangster rap made it more urgent, more sensational, and more vital than any other music in the marketplace, rap or otherwise. Gangster rap wasn’t just artists rapping about what they saw, but also what they did. They were products of the streets whose art reflected their life experiences—gangs, violence, drugs, and sex.

This is masterfully illustrated by Ice-T’s landmark 1988 single “Colors,” the first rap song that was the title track of a major motion picture. The film from Academy Award nominee Dennis Hopper showcases an experienced cop (Academy Award winner Robert Duvall) and a rookie (eventual two-time Academy Award winner Sean Penn) as partners who patrol the streets of Los Angeles as gangs begin taking over the city.

Using Ice-T’s “Colors” in such a high-profile film marked a significant development for gangster rap because, up to this point, rap songs were typically used in small-scale independent films about hip-hop culture (1983’s Wild Style and 1985’s Krush Groove) and films about breakdancing (1984’s Breakin’, Beat Street, and Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo). By contrast, Colors was a Hollywood studio film starring two of the industry’s biggest names—Duvall and Penn—as well as such future stalwarts as award-winning actors Don Cheadle and Damon Wayans.

In unflinching terms, “Colors” mirrors the film’s subject matter and details the kill-or-be-killed gangbanging lifestyle that was ravaging Los Angeles. The video version of the song features Ice-T providing two distinct perspectives. One came from the vantage point of an active gang member detailing his status as a “nightmare walking, psychopath talking” gangster. The other commentary arrives in spoken-word passages after each rapped verse. This viewpoint is from the eyes of a kid who wishes he was not a part of the madness. Strikingly, Ice-T articulates the pain, disappointment, and struggle from both characters’ perspectives, even though they put up dramatically different facades.

NIGHTMARE WALKING, PSYCHOPATH TALKING GANGSTER: Tell me what have you left me / What have I got? / Last night in cold blood my young brother got shot / My homeboy got jacked / My mother’s on crack / My sister can’t work ’cause her arm show tracks / Madness, insanity / Live in profanity / Then some punk claimin’ they’re understandin’ me / Give me a break / What world do you live in?/ |

VOICE OF REASON: My brother was a gangbanger / And all my homeboys bang / I don’t know why I do it, man, I just do it / I never had much of nothin’, man / Look at you, man / You’ve got everything going for yourself / And I ain’t got nothing, man / I’ve got nothing / I’m just living in the ghetto, man / Just look at me, man / Look at me |

The song continues in kind, alternating between the chilling commentary of the two characters:

NIGHTMARE WALKING, PSYCHOPATH TALKING GANGSTER: My game ain’t knowledge, my game’s fear / I’ve no remorse, so squares beware |

VOICE OF REASON: No matter whatcha do, don’t ever join a gang / You don’t wanna be in it, man / You’re just gonna end up in a mix of dead friends and time in jail |

Ice-T says that showing the pros and the cons of street life is essential in order to accurately depict the lifestyle and to remain credible with the music’s target audience.

“If you’ve actually been out there with gangsters and drug dealers, they’re going to keep a close eye on you,” Ice-T said in an August 2000 interview. “There’s no true way to deal with gangsterism without showing both sides of it and being honest.

“My music was an attempt for me to show [life on the streets], but be truthful,” Ice-T added. “And the truth of the matter is that when you’re winning, it’s the most exciting thing in the world. But the downside is a motherfucker.”

With “6 ’N the Mornin’,” Rhyme Pays, and then “Colors,” Ice-T brilliantly showed both sides of the lifestyle, putting his stamp on the emerging gangster rap movement in the process. He became known as the genre’s truth teller, a high-profile poet and provocateur whose aim was not merely to agitate, but to educate the world about the crises transpiring in black urban America.

As Ice-T was riding high thanks to the success of “Colors” (which was named the nineteenth greatest hip-hop song of all time by VH1 a decade after its release), another 1988 release would change the course of rap history forever. It also put a previously anonymous Los Angeles suburb on the national radar, thanks in large part to a song then-emerging rapper-producer Dr. Dre didn’t want to release because he thought no one would care about it.