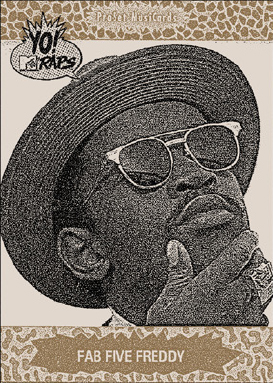

Fab 5 Freddy (left) and Ice-T attend a fifteenth anniversary screening of the movie Wild Style in Los Angeles on June 18, 1998.

ALTHOUGH RAP WAS KNOCKING ON MAINSTREAM AMERICA’S DOOR IN 1988, IT WAS GANGSTER RAP THAT KICKED THE DOOR OFF ITS HINGES.

Gangster rap was enjoying increasing success as N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton and Eazy-E’s Eazy-Duz-It surged in popularity. Ice-T, now thirty years old, was riding high on the success of two gold albums and was preparing to embark in earnest on his acting career, while eighteen-year-old Scarface was joining the Ghetto Boys (later changed to Geto Boys), Houston’s premier rap outfit. Several other future gangster rap figures, including DJ Quik (eighteen) and Compton’s Most Wanted’s MC Eiht (twenty-one), were releasing music independently in Compton. At the same time, DJ Muggs (twenty) was one-third of the 7A3, his group before Cypress Hill.

In 1988, America’s inner cities were still reeling from Reagan’s devastating policies and the severe drug laws that helped to fill a burgeoning number of private prisons that profited from government and corporate contracts. This was seen by many as a new and diabolical twist to crush and enslave black people. The irony that Reagan’s “War on Drugs” initiative was at odds with his role in the Iran-Contra affair, which was a catalyst for drug distribution and use in America’s inner cities, especially South Los Angeles, was lost on no one.

TIMELINE OF RAP

1989

Key Rap Releases

1. De La Soul’s 3 Feet High and Rising album

2. The 2 Live Crew’s As Nasty As They Wanna Be album

3. Big Daddy Kane’s It’s a Big Daddy Thing album

US President

George H.W. Bush

Something Else

The Tiananmen Square Massacre rocked China.

This reality was articulated eloquently by rappers who were experiencing the aftermath of this scourge firsthand. The authenticity and artistry of their words fueled the sale of millions of records and made them the de facto spokesmen for the hood. But the outlets that usually supported popular music at the time—namely radio and MTV—typically shunned rap in general, and gangster rap in particular. The reality of—and the art inspired by—what was happening in the streets of major cities throughout the country was essentially being overlooked by the local and national media.

Thus, consumers were forced to turn to alternative outlets to hear, discover, and enjoy the rap and gangster rap records from artists such as Schoolly D, Ice-T, N.W.A, and others who were selling hundreds of thousands of copies. Word of mouth, college radio play, and a smattering of mix shows on commercial radio became key resources for rap fans. The popularity of rap at college radio, in particular, was an important step to opening the minds of a generation of young, white, privileged kids to the plight of being black. The cultural impact of this was a tremendous catalyst in bringing young whites and blacks together and would later be seen as an important step in electing a black man to the highest office in the world.

Where rap (and especially gangster rap) got next to no backing was where most would have assumed it would get the most support: commercial black radio. At the time, black radio was playing highly stylized and sanitized artists who sang about love, money, and parties, and whose music was largely devoid of any social commentary or reality. Rappers and their music were the polar opposite of what black radio and BET (Black Entertainment Television) were promoting as black music. Whereas R&B artists wore suits or custom-designed outfits, rappers wore white T-shirts, khaki jeans, baseball hats, and sneakers. Even worse, rappers cursed on records and used the words nigger and nigga with increasing regularity.

“When we were young, all the old R&B heads thought that rap was a piece of shit,” the D.O.C. said. “They didn’t give a fuck about it. It wasn’t going to be shit.”

Even though most rappers made “clean” versions of their songs, black radio program directors were reportedly repulsed by the images, graphic language, and subject matter of rap.

“Those lyrics were something that the parent police just didn’t want broadcast on the airwaves,” DJ Quik said. “The PTA, they wasn’t happy about some of the shit we were doing. That’s the total opposite of what they’re teaching in school. I don’t mean to make fun of it, but that shit was belligerent, audacious, explicit. . . . This shit was wild. It was just debauchery at its finest.”

The way rap—especially gangster rap—was virtually ignored at radio stations did not match the music’s surging popularity with the radio stations’ listening audiences.

“Rap was still like stepkids, but they were selling shitloads [of records],” said Chris LaSalle, who worked in promotion and marketing at Profile Records (Run-DMC, Dana Dane, Rob Base, and DJ E-Z Rock) from 1985 until 1989.

There was such a disconnect between black radio stations and the rap world that artists openly began taking shots at the radio establishment that had largely shunned them. On their “Rebel Without a Pause” single, for instance, Public Enemy’s Chuck D rapped, “Radio, suckers never play me.” Also in 1988, pioneering Seattle rapper Sir Mix-a-Lot buttressed the video for his “Posse on Broadway” with skits featuring real-life local radio DJ Nasty Nes. In the video’s open, Nes is approached by the rapper and his crew, who ask him to play their new song on his radio show. Nes balks, saying that his radio station plays real music, not rap. By the end of the video, Nasty Nes is playing the record on the station repeatedly and is shown wearing a gold chain and hat à la Sir Mix-a-Lot’s posse.

Just as rap struggled to get on the radio, rap videos had limited exposure, enjoying play almost exclusively on regional public television shows such as New York’s Video Music Box, which was launched in 1983 by Brooklyn entrepreneur Ralph McDaniels. Even BET provided minimal support of videos for early rap hits, including Run-DMC’s “Rock Box” and “King of Rock.”

PHYSICAL LOCATION: New York, New York

YEAR FOUNDED: 1981

INITIAL CONCEPT: MTV was built as an album-oriented rock music channel

FIRST VIDEO PLAYED: “Video Killed the Radio Star” by The Buggles

FIRST VIDEO MUSIC AWARDS: 1984

TOP FIVE VIDEOS OF 1988:

“Sweet Child o’ Mine” by Guns N’ Roses

“Pour Some Sugar on Me” by Def Leppard

“Need You Tonight/Mediate” by INXS

“Rag Doll” by Aerosmith

“Man in the Mirror” by Michael Jackson

Billboard’s Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs

Michael Jackson, “The Way You Make Me Feel”

Keith Sweat, “I Want Her”

Billy Ocean, “Get Outta My Dreams, Get Into

My Car”

Pebbles, “Mercedes Boy”

Johnny Kemp, “Just Got Paid”

Bobby Brown, “Don’t Be Cruel”

NOTE: The lone song featuring a rapper to top Billboard’s Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart in 1988 was Rick James’s “Loosey’s Rap,” which featured female rapper Roxanne Shanté and was included on his 1988 album, Wonderful.

“They turned down those two videos off the bat,” LaSalle said in a 1986 interview with Billboard, “because they were too hard.”

In 1988, even though rap was selling records in numbers rivaling its rock and R&B counterparts, it did not have the mainstream media penetration other musical genres enjoyed. That all changed almost instantly with one television program.

Yo! MTV Raps debuted on MTV on August 6, 1988, bringing rap—and later gangster rap—to America’s living rooms. The premiere episode was hosted by Run-DMC and featured D.J. Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince.

In addition to being the third-highest-rated show after MTV’s Video Music Awards and Live Aid, Yo! MTV Raps was groundbreaking on several other levels. For one, MTV had long shunned videos by black acts. Founded in 1981, the network had developed such a reputation for not supporting music by black musicians that rock icon David Bowie called out VJ (video jockey) Mark Goodman during a 1983 interview.

“The only few black artists that one does see are on about 2:30 in the morning until about 6:00,” Bowie said. “Very few are featured prominently during the day.”

Future rap power brokers noticed the same problem. “When I was a kid, you waited for Michael Jackson or Prince or Lionel Richie to come on,” said the Roots’ Questlove. “You’d have to sit through four hours of Thomas Dolby and Genesis and Duran Duran.”

Even Michael Jackson, whose blockbuster Thriller album was released in 1982, had a hard time getting videos aired on MTV. In 1983, though, the video for Jackson’s “Billie Jean” became a staple on the channel, making it the first video from a black act to get major rotation on the network.

Although Thriller would quickly become the bestselling album in music history, few videos from black musicians—and, by default, even fewer rap videos—earned a spot on MTV. Those that did typically had some sort of rock crossover appeal, such as Run-DMC’s “Walk This Way” collaboration with rock band Aerosmith and clips from white rap group Beastie Boys’ album Licensed to Ill, both released in 1986.

“Basically, these rappers had to emulate rock and roll, in order to get on MTV,” said author and producer Dan Charnas.

Yet, the unofficial and unstated barrier between rap and white America vanished once Yo! MTV Raps hit the airwaves. The program, which arrived at a time when MTV had approximately two hundred and forty thousand viewers at any given minute, featured interviews with artists and music videos, eventually expanding to include weekly performances from artists as well.

Yo! MTV Raps was created by one-time MTV production assistant and future major motion picture director Ted Demme and fellow music documentarian Peter Dougherty. A serious rap fan and proponent of the genre, Demme essentially willed the show into existence. “I was always a hip-hop fan growing up in New York and just thought there was a lack of hip-hop music on the channel, and back then, obviously a lack of black music on the channel,” Demme said.

Despite Demme’s perseverance with the MTV brass, a lack of interest by the network’s power players meant Demme and Dougherty were given just a few thousand dollars to shoot a pilot. But once the Run-DMC–hosted episode got great ratings, MTV quickly ordered the show into production. For the host of the show—which aired on the weekends—MTV tapped Fab 5 Freddy, a visual artist who is credited with bridging the gap between New York’s uptown hip-hop scene and the city’s downtown art world. His status in the Manhattan scene led him to be name-dropped on Blondie’s 1981 single “Rapture.” Blondie singer Debbie Harry rapped that “Fab 5 Freddy told me everybody’s fly” on the song, which would later be a full circle moment for the man born Fred Brathwaite. The video for “Rapture” is considered the first video featuring rap played on MTV. Seven years later, Fab 5 Freddy was hosting Yo! MTV Raps and giving much of the world its first look at rap videos, interviews with rappers, and rappers performing on television.

MTV VIDEO MUSIC AWARDS

Australian rock group INXS was nominated nine times and won five awards at the 1988 MTV Video Music Awards. George Harrison and U2 were each nominated eight times, while no rap videos were nominated in any category. Rap was represented at the ceremony by the Fat Boys, who performed their “Louie Louie” and “The Twist” singles with Chubby Checker, and by D.J. Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince, who, with Justine Bateman, presented the Best Stage Performance in a Video award to Prince (featuring Sheena Easton for “U Got the Look”).

YO! MTV RAPS VS. RAP CITY VS. PUMP IT UP!

Leslie “Big Lez” Segar was one of the hosts of BET’s Rap City from 1993 to 2000. She looks at the three major rap video shows.

Left to right: Warren G, Leslie “Big Lez” Segar, and Kurupt celebrate Big Lez’s birthday at the El Rey Theatre in Los Angeles in 1998.

YO! MTV RAPS (MTV, 1988–95, BASED IN NEW YORK): “Yo! MTV Raps was groundbreaking, without question. They got people to really sit down and show you who they were, that they were artistic, creative, prolific, human, and that they liked to have fun and it wasn’t all about the music. It showed [the artists] weren’t as volatile as their rhymes made them seem.”

RAP CITY (BET, 1989–2008, BASED IN WASHINGTON, DC): “We wanted to do not just what was on the Top 10 Billboard and take hip-hop out of the studio and into the backyards of all these people. We would go everywhere. We went to Chicago and would be at [prominent independent urban music retailer] George’s Music Room, where Common would get love. Then we’d go down to Houston, where [Rap-A-Lot Records owner] Lil’ J [J. Prince] was shooting horses. Nobody thought hip-hop would be at a farm or a ranch. Then we had the whole dancehall era, [when we] would go hang out in Jamaica with [reggae artists] Buju Banton and Patra, and [we’d] really show people what the fuck is up with all this music.”

PUMP IT UP! (FOX TV, 1989–1992, BASED IN LOS ANGELES): “Dee Barnes was one of the first female hosts that I’d seen in a male-dominated thing do her hip-hop thing. She rolled out the welcome mat for me as a female, making it be like, ‘Okay. Go ahead and do your thing and show these boys you represent hip-hop to the fullest.’ She didn’t try to sell T&A. She wasn’t flirtatious. She didn’t ask ridiculous questions. She asked real, poignant, hardcore things about the lyrics, about politics, the labels.”

To this point, popular rap videos such as Run-DMC’s “Walk This Way” and Beastie Boys’ “(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (to Party!)” and “No Sleep Till Brooklyn” were relatively straightforward performance pieces. Even the clip for Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message” featured Melle Mel rapping on a stoop and on a city street for much of the video before he and his crew are apprehended and hauled away in a police car. Yes, Melle Mel and the rest of the Furious Five were in deplorable surroundings, but they were rapping about them, not helping create them. They were reporters, not perpetrators.

Similarly, the video for Ice-T’s “Colors” featured scenes from the 1988 film after which it is named. As Ice-T raps in a graffiti- and debris-adorned alley, images of actor Sean Penn’s character are shown chasing and abusing the blue-and red-clad actors portraying gang members in the movie. As striking as the video for “Colors” was, Ice-T acted as a narrator in the clip, much as Melle Mel had done in the “The Message” video.

The video for N.W.A’s “Straight Outta Compton” was more visceral. The raucous clip not only featured the city of Compton getting targeted by police, but also showed group members Ice Cube, Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, MC Ren, and DJ Yella being chased, harassed at gunpoint, and ultimately arrested by the police. The gritty clip presented a seemingly all-out affront by the police against Compton and against N.W.A. The police officers in the video were white and each member of N.W.A was black. It was a visual presentation of the antagonistic relationship between white police and black citizens that led N.W.A to make “Fuck tha Police.”

Just as Ice-T had ratcheted up the criminal intensity compared to Schoolly D’s music, N.W.A put themselves squarely in the crosshairs of the police, the government, and the overall oppressive white American system with the video for “Straight Outta Compton.” With the videos for “Colors” and “Straight Outta Compton,” it was clear that rap music videos had gone from largely benign to confrontational, and thanks to MTV, these videos were now being seen by millions of kids around the country and the world.

The videos had different effects on different segments of the population. “People were able to see, like, ‘Damn. We’re selling dope here in Chicago, too,’” Compton’s Most Wanted front man MC Eiht said. “There were neighborhood dudes everywhere and [getting a video played on Yo! MTV Raps] just opened the door for all neighborhood dudes to connect on our level.”

Yo! MTV Raps exposed its viewing audience to the gang, drug, and crime culture. For the first time, millions of white fans could listen to rap and watch rap music videos created by artists from the ghettos of the United States without leaving the comfort of their homes. There was no need to wade into the Bronx, Brooklyn, or Los Angeles to experience rap; it was being broadcast into households across the country. For most viewers, the videos for Ice-T’s gang treatise “Colors” and N.W.A’s abrasive “Straight Outta Compton” were among their first audio and visual insights into the world of the gang-riddled streets of Los Angeles, the epicenter of gangster rap.

This was a significant step in the development of rap music and hip-hop culture, because before Yo! MTV Raps hit the airwaves, only Whodini, Run-DMC, LL Cool J, the Fat Boys, and Beastie Boys were among the rap acts to appear for any meaningful amount of time on television, in print, in movies, and on the radio. And even when these acts enjoyed mainstream coverage, they were typically framed as part of a new fad: rap music.

But another common bond between all these acts was simple and obvious: All of them were from New York. Rap was created in New York, the labels releasing rap were mostly based in New York, and the artists releasing material were mostly from New York. Perhaps unintentionally, but definitely significantly, Yo! MTV Raps showed, for the first time, that rap was being produced in more places than just the Empire State.

With MTV’s early support of Southern California’s Ice-T, King Tee, N.W.A, and Eazy-E; Philadelphia’s Schoolly D, Steady B, and D.J. Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince; Miami’s 2 Live Crew; Seattle’s Sir Mix-a-Lot; and Oakland’s Too $hort, among others, rap fans got to experience what artists from different parts of the country looked and sounded like.

“That was the first place where people from New York could see what was going on in Texas,” Yo! MTV Raps producer Todd 1 said. “People from Texas could see what’s going on in Miami. People from Miami could see what was going on in California.”

“They were programming a video channel that was more popular than radio,” LaSalle said. “That’s where you went to see hits—and breaking stuff, too. Yo! MTV Raps was definitely breaking the new rap.”

“Every record that I saw on Yo! MTV Raps, I went and bought it as a fan,” said DJ Quik, who later signed to Profile Records. “This was a product for sale, and it was good? Build it, they will come. I went and bought it.”

But with that power came pressure. Yo! MTV Raps banned N.W.A’s “Straight Outta Compton” video, succumbing to the pressure from police organizations, politicians, and others due to N.W.A’s “Fuck tha Police.” But the show also gave Ice-T, N.W.A, and other rappers something more valuable, something that went beyond video exposure. It gave them the opportunity to speak on camera. For the first time, rappers were being interviewed on television on a consistent basis and were becoming more than pictures on album covers or in urban zines. They were now people with thoughts, ideas, and personalities beyond the music. Through interviews with Ice-T, N.W.A, and others, the predominantly white audience was able to experience firsthand the intelligence and insight rappers used while explaining the sobering realities depicted in their music.

“The videos made those guys, made that movement,” the D.O.C. said. “When Eazy got on TV, you couldn’t deny it. The guy was so charismatic, and his look was so cool, and his swag was so dope. And the music was fuckin’ great.”

In Fab 5 Freddy, the rappers also got an interviewer with a rap pedigree who was at least sympathetic to—and always supportive of—the opinions and perspectives the artists presented. Hard-hitting journalism this was not, but the average viewer was still learning more about the artist than they ever had before.

Furthermore, even though he was part of hip-hop culture (he released the oft-sampled “Change the Beat” single with Beside in 1981), given Fab 5 Freddy’s art background, he was more worldly than many of the artists he was interviewing. In many ways, he was the Gertrude Stein of rap, with Yo! MTV Raps being equivalent, in a sense, to her Paris salon, where great creative minds would mix, mingle, and cross-pollinate ideas, perspectives, and art. Like Stein, he was a host and champion who used his influence to get the artists a seat at the table.

“Every generation has that one place where everything cool happens,” radio personality Miss Info said. “That’s where you find out what you’re supposed to like, whether it was American Bandstand or Solid Gold or Soul Train. And that’s what Yo! MTV Raps was for us.”

For gangster rap, in particular, casting Fab 5 Freddy was also significant. He was from Brooklyn, not Los Angeles. Interviewing artists from Southern California provided him with the opportunity, much like the overwhelming majority of the Yo! MTV Raps viewers, to see, experience, and learn about something he had little knowledge of: the urban Los Angeles experience and its gang culture, lowriders, and swap meets.

Thus, Fab 5 Freddy’s interviews with gangster rappers often were, in a sense, like first dates. There wasn’t a lot of deep conversation transpiring. It was more about getting to know the artists, even though, in the case of Ice-T and N.W.A, they had been releasing successful material for more than a year before their interviews.

“The whole L.A. vibe was kind of new,” the D.O.C. said. “The look, the way they walked and talked, and the things that they said, all that shit was brand-new. So, it kind of swept through the country just like crack did.”

During an April 1989 interview, N.W.A took Fab 5 Freddy to the Compton Fashion Center, a flea market, also known as a swap meet. Having N.W.A members as tour guides provided a look into the group’s world. Eazy-E said that that’s where the group picked up their sunglasses (Locs), shirts, and Levi’s. When Fab 5 Freddy asked Dr. Dre to name the most incredible thing he’d ever gotten at the Compton Fashion Center, he responded by saying, “Females.”

As the group rode on the flatbed of a truck from Compton to Venice Beach, Fab 5 Freddy asked Ice Cube to speak about the violence consuming the Los Angeles metropolitan area. “After a lot of people saw Colors, they thought L.A.’s just all violent,” Ice Cube said. “That’s not true. Yes, it is some hard parts, but then again there is some good parts. But I like to say, ‘When a brother kills a brotherman, the only people that’s happy is the other man [a white man].’”

Although N.W.A was quickly gaining a reputation as profane, anti–law enforcement, misogynistic, and violent, Ice Cube’s comment showed that there was more to the group’s music than just blind rage. Perspective, passion, and pain informed N.W.A’s music and Yo! MTV Raps viewers got to watch Ice Cube defend and present his city on his terms.

“It brought you into their world and it let you see rap from a real organic standpoint and how the artists actually embodied the hoods that they came from and the reason why the music is the way it is,” said EST, front man of Philadelphia rap group Three Times Dope. “It was the show to be on if you were in hip-hop at all.”

During a different 1989 interview with Fab 5 Freddy, Ice Cube provided context for his lyrical stylings. He mentioned that he listened to the Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron, spoken-word artists from the sixties and seventies whose black nationalist material and social commentary predated, directly influenced, and was sampled by scores of rap artists. The Last Poets, for instance, filled their 1970 self-titled album with spirited spoken-word poetry that championed the need for radical change in the black community (“Run, Nigger”) and a proactive stance to initiate said change (“Niggers Are Scared of Revolution”). For his part, Gil Scott-Heron’s 1970 album, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, featured songs that traced the evolution of the way blacks were perceived in America, from “darkie” to “slave” to “nigger” to the assassinations of Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (“Evolution [And Flashback]”). “They give us the flavor so we know what to talk about,” Ice Cube said. “We know what people like.”

“Every generation has that one place where everything cool happens. . . . That’s what Yo! MTV Raps was for us.”

MISS INFO

And what they liked was the gangster rap lifestyle they saw portrayed in the videos Yo! MTV Raps played. In addition to bringing awareness to gang culture, the program helped spread it, giving light to a secret society of sorts.

“It really felt like you were getting a bird’s-eye view on the back of somebody’s motorcycle or the back seat of somebody’s lowrider rolling down the street dodging bullets, catching how it’s really going down,” said Leslie “Big Lez” Segar, a host of BET’s Rap City video program from 1993 to 2000. “All the things you read in the paper and all the things you see on TV, even though they edit and gloss over it, what gangster rap did was it gave you a front-row seat to what was happening. So you almost felt like you lived on the block in Watts, that you can’t be sitting on your porch because you’re about to duck bullets if a car driving by too slow was about to roll up on you. You kind of felt like you were in the video with them.”

But seeing something and living it are two dramatically different things. Wearing a cowboy hat does not make someone a cowboy.

“It got those dudes in Kansas and North Dakota, where they had never known about gangbanging and colors, now you’re starting to see kids wearing Raiders jackets and hats and rags,” MC Eiht said. “Sets that are from Compton, you’re seeing them all the way out in South Dakota and Wisconsin. . . . Everything was secretive until we started rapping and Yo! MTV Raps started putting our videos up so everybody could relate to what we were talking about because a lot of people didn’t understand what was going on. They’d hear a record and, ‘Oh. They’re shooting each other.’ ‘Why he got on red?’ ‘Why he got on blue?’ I always tried to incorporate what was going on with the gangbanging in my videos. It gave people a way to symbolize [identify] with us.”

Fab 5 Freddy: The New York hip-hop pioneer was involved in the genre’s growth throughout New York City and, eventually, the world. His early work as a rapper (he released the song “Change the Beat” and embarked upon the first European hip-hop tour in 1982) and visual artist (he introduced the white downtown art scene to the black uptown graffiti world) led to film work, most notably as an actor and producer on the seminal 1983 hip-hop film Wild Style. The Yo! MTV Raps card used an alternate appellation.

Doctor Dré and Ed Lover (and T-Money): Doctor Dré and T-Money earned their stripes as college radio hosts and as members of the rap group Original Concept, which released Straight From The Basement Of Kooley High! with Def Jam Recordings in 1988. Ed Lover was a member of the rap group No Face before joining the Yo! MTV Raps fold.

Seeing gangbanging portrayed in rap videos gave millions of fans around the country a look at a lifestyle they were utterly unfamiliar with. Ironically, one of Gil Scott-Heron’s most famous works was “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” a 1970 selection in which the New York–based artist railed against the corporatized, romanticized, and whitewashed version of America often presented on television and in the media. Gil Scott-Heron ends the song by saying “The revolution will not be televised. . . . The revolution will be live.”

Yo! MTV Raps wasn’t live, but it was revolutionary in many ways. In March 1989, it graduated from its initial weekend slot and began airing Monday through Saturday, with weekday duties being handled by New York DJ Doctor Dré (not to be confused with N.W.A’s Dr. Dre) and comedic-minded hip-hop fan and security guard Ed Lover. Unlike Fab 5 Freddy, who showcased his swagger during his screen time, Doctor Dré and Ed Lover (and occasional special guest host T-Money) brought a balance of rap knowledge and levity to the program through their routines, skits, and slapstick interactions.

The additional programming time gave rap exponentially more viewers, offered a new voice to the voiceless, and provided a visual look into some of America’s most overlooked communities courtesy of some of its most articulate and informed spokesmen.

“It really was an ambassadorship for hip-hop to mainstream America,” author, screenwriter, and pioneering rap journalist Nelson George said of Yo! MTV Raps.

Chilli, of R&B trio TLC, added: “To have a show that showed some love for rap like that, I just thought that was the greatest thing they’ve ever done on that network.”

Almost overnight, Yo! MTV Raps had supplanted radio in the rap world. “Yo! MTV Raps enabled me to reach the masses of other project, neighborhood, wannabe gangbanger, and gangbanger type of dudes because we didn’t have no outlet,” MC Eiht said. “On the West Coast, we had KDAY, they played a little Eazy-E, a little Compton’s Most Wanted, but being able to go nationwide as far as a video was concerned, it enabled smalltime Compton’s Most Wanted to be internationally known because Yo! MTV Raps was everywhere. . . . It just catapulted us from being local heroes to national gangbang rappers, or gangster rappers is what people wanted to call it. It enabled us to connect with those dudes in Chicago, Brooklyn, Bronx, down South in Florida, the Atlantas and the Texases. Wherever dudes congregated and called themselves that, they were able to now see [people just like them on television].”

The dirty secret of black urban American life was now, for the first time, being seen and heard by millions of fans, black and white alike. Rap had always been competitive, and Yo! MTV Raps gave rappers an extra incentive to deliver their best material. On the one hand, it provided a platform to showcase the best artists, the rappers with the most revered rhymes, the artists with the best music, and the acts with the most remarkable videos. The exposure it provided also helped a handful of rappers become rich and famous. On the other hand, Yo! MTV Raps was a tremendous marketing tool to sell a lifestyle to hundreds of thousands of fans who—especially if they were black—remained poor, oppressed, and subject to wanton harassment and police brutality. The handful of rappers who became rich and famous had just moved up several tax brackets.

Furthermore, gangster rap was being seen and heard at a time when American culture was shifting from reading and listening in order to digest its information to getting it by watching television. Viewers were now aware of what was happening in poor diverse neighborhoods. In 1988, Chuck D famously said, “Rap is black America’s TV station.” If so, then Yo! MTV Raps was akin to its nightly news, a snapshot of the most pressing issues of the day.

The rappers took full advantage of the platform, too. In an interview during one of N.W.A’s Yo! MTV Raps appearances in 1989, Dr. Dre taunted the group’s detractors while likely energizing fans who rallied behind the group’s explicit material. “People been sweating us for our lyrics and stuff like that,” the rapper-producer told Fab 5 Freddy. “We figured since they sweated us, we’re gonna make the next album worse.”

The next N.W.A album, though, would not feature one of the group’s most significant members. He was the only member who wasn’t from Compton, and he was about to show the world that he knew how to survive in South Central.