Left to right: Ice-T, Hen Gee, Chuck D, and Ice Cube.

IN 1989, URBAN AMERICA AND THE WORLD WERE FALLING DEEPER INTO CHAOS.

As former director of central intelligence and vice president George H. W. Bush was sworn into office as president, America’s inner cities continued to disintegrate, thanks in large part to Reaganomics. At the same time, US politicians and their wives continued to rail against the lyrics of gangster rappers. The Lockerbie bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 claimed two hundred and seventy lives and the Exxon Valdez oil spill polluted Alaska’s Prince William Sound with two hundred and seventy thousand barrels of crude oil. The savings and loan crisis erupted, costing taxpayers more than $160 billion—and their life savings in many cases. In Tiananmen Square, one million Chinese protesters stood up against their oppressive government’s violence and demanded a better democracy, while President Bush invaded Panama to capture and arrest de facto leader Manuel Noriega. Many people watched these events unfold live on CNN, a 24/7 news network that was the go-to channel for nonstop coverage of the world in chaos.

TIMELINE OF RAP

1990

Key Rap Releases

1. Ice Cube’s AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted album

2. Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet album

3. MC Hammer’s “U Can’t Touch This” single

US President

George H.W. Bush

Something Else

East and West Germany reunified.

The threat of violence had firmly ensnared black neighborhoods across America, and it seemed that crisis followed crisis. In the Bronx, a five-year-old kindergarten student was found at school in possession of a handgun. In Miami, riots rocked the city after a police officer shot and killed a twenty-four-year-old unarmed black man.

Meanwhile, in South Central Los Angeles, preteens and teenagers joined gangs at an alarming rate in order to survive the urban decay and violence on the streets. Gangs grew more powerful and more violent due to an unprecedented influx of drugs and money spurred in part by the fallout of Reaganomics, which left ghetto America in a frighteningly vulnerable state. Economic and educational resources were becoming increasingly scarce while alcohol, drugs, and guns were becoming more readily available.

For the young people growing up in this chaotic environment, it meant ditching collared shirts and slacks for the gang uniform of a Pendleton shirt, Levi’s 501 jeans, Chuck Taylors (with your gang name on the tongue), a hair net, braids, and a golfer hat. On the one hand, the change in attire put their lives at risk, but on the other hand, it provided them with a form of brotherhood and safety largely absent from their lives.

San Diego gangster rapper Mitchy Slick had been gang affiliated for more than half of his fifteen years in 1989. He remembers the chaos and desperation of those days. “People in impoverished situations, they’re going to look to each other for help. They’re going to come together. . . . When I was coming up, they didn’t have no gang intervention. It wasn’t no, ‘Don’t wear these colors to school.’”

At the same time, Ice-T, thirty-one, scored his third consecutive gold album with The Iceberg/Freedom of Speech . . . Just Watch What You Say!, and the Ghetto Boys changed their lineup, adding eighteen-year-old Scarface to the mix. The result was a surge in popularity for the group in addition to Texas being put on the gangster rap map. Meanwhile, Eazy-E, now twenty-five years old, was touring the country with N.W.A, and the group was on their way to being the first gangster rap group certified platinum with a million records sold. Inspired by their surroundings, this handful of artists provided a voice to the millions of blacks suffering through poverty, oppression, and a lack of equal access to America’s vast economic and social resources. For the artists and listeners alike, there was a sort of cathartic experience in creating and consuming the music. It was a way to connect on a visceral level like never before.

But as select rappers were escaping from the type of poverty they rapped about, a new problem emerged at one of rap’s most successful upstart labels. Despite its commercial success, all was not well at Eazy-E’s Ruthless Records. Ice Cube had grown disillusioned with what he thought was a massive underpayment for his services. After refusing to sign a contract and accept a check for his past work as a writer and performer on Eazy-E’s Eazy-Duz-It and N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton albums, Ice Cube left N.W.A during the height of the group’s popularity. In respect to where the group was in their career arc, it was akin to John Lennon or Paul McCartney leaving the Beatles after the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Ice Cube and Eazy-E may have been from the hood, but they were now part of the legit world of the music business. Not having contracts signed at the beginning of their relationship was a big misstep that manager Jerry Heller should have known could, and would, come back to haunt Eazy-E, as it gave Ice Cube a chance to escape what he saw as an unfair deal.

As he worked through the dissolution of his relationship with Eazy-E, Ruthless Records, and Jerry Heller, Ice Cube sought counsel from the group’s publicist. “Pat Charbonnet was very instrumental in me recognizing that the situation with Ruthless and Jerry Heller just wasn’t right,” Ice Cube said. “Just by her being so smart about the business, I ended up naming her my manager, and the first person she went to was [Priority Records co-owner] Bryan Turner. She said: ‘Cube’s solo. You want to give him a deal? Or, if not, we’re going to go get it somewhere else.’ So he stepped up, and I’m glad he did.”

Although Ice Cube often conceptualized N.W.A’s thematic direction and had the idea for the group’s landmark “Fuck tha Police,” many fans and industry insiders viewed him as just another member of N.W.A and little else.

RUTHLESS RECORDS STRIKES GOLD & PLATINUM

J.J. Fad, Supersonic, June 27, 1988, Gold album, September 30, 1988

Eazy-E, Eazy-Duz-It, November 23, 1988, Gold album, February 15, 1989 (Platinum, June 1, 1989, Double platinum, September 1, 1992)

N.W.A, Straight Outta Compton, August 8, 1988 (initial version), Gold album, April 13, 1989 (Platinum, July 18, 1989, Double platinum, March 27, 1992, Triple Platinum, November 11, 2015)

“I don’t think anyone knew what they were losing when [Ice Cube left Ruthless],” the D.O.C. said. “I didn’t even really give it a whole lot of thought because I was thinking about my shit. But when he left, the spirit of that group was gone.”

That’s because Ice Cube was N.W.A’s “lyricizer,” as Eazy-E repeatedly put it to the press. He was the artist whose words and song ideas helped define N.W.A’s early music. Eazy-E was the group’s “conceptualizer,” and Dr. Dre its “musicalizer.”

Eazy-E was also the highest-profile member of N.W.A, and Ruthless Records was his company. He was the one with the solo project, Eazy-Duz-It, an album that was selling as robustly as N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton. Eazy-Duz-It was certified gold in February 1989. Thus, Eazy-E was the star of N.W.A, a king among kings in the richest talent pool in rap history. Dr. Dre was positioned as the crew’s second star thanks to his musical genius, proficient production, and his visibility from rapping on the N.W.A single “Express Yourself,” which had gotten extensive play on Yo! MTV Raps.

As word spread that Ice Cube had left N.W.A, rap insiders and casual fans alike had a number of concerns about his career given N.W.A’s potency as a group. Ice Cube was now without Eazy-E, MC Ren, and Dr. Dre to share the verbal and lyrical load. Furthermore, the Dr. Dre–produced No One Can Do It Better from the D.O.C. and “No More Lies” from singer Michel’le were certified gold in 1989. It appeared that Ice Cube would suffer without the benefit of Dr. Dre’s (and DJ Yella’s) production prowess and the industry clout Ruthless Records had amassed by that point.

“[Ice Cube] had to set out to prove that he was one of the most important parts of this fuckin’ band,” DJ Quik said.

Although Ice Cube and Dr. Dre wanted to work together on Ice Cube’s solo album, it was blocked. “Jerry Heller vetoed that,” Ice Cube said. “So since he vetoed that shit—and I’m pretty sure Eazy didn’t want Dre to do it. But Dre did want to do it. We gotta put that on record. Dre wanted to do my record, but it was just too crazy with the breakup of [N.W.A]. The breakup snowballed into some shit.”

Other things were snowballing, too. As gangster rap started to tighten its grip on the creative and sonic direction of rap, an explosion of conscious rap occurred in New York. The pro-black work of Public Enemy and the now-politically minded work of Boogie Down Productions helped lead the charge. Several other voices were also making a dent in the rap marketplace, many of them from the New York metropolitan area. Long Island, New York, trio De La Soul delivered what was deemed a hippy take on rap, but their 3 Feet High and Rising showed remarkable range with a deft mix of social commentary, humor, and esoteric lyrics. Revered Long Island hardcore rap duo EPMD released its second collection with Unfinished Business. And esteemed Brooklyn lyricist Big Daddy Kane released his acclaimed second album, It’s a Big Daddy Thing, a well-rounded album full of boasts, social commentary, and sexually driven lyrics. EPMD’s, De La Soul’s, and Big Daddy Kane’s albums all went gold within six months.

AS N.W.A AND Eazy-E began dominating rap in general and gangster rap in particular, Eazy-E’s Eazy-Duz-It album was flying off record store racks. In this undated press release from Priority Records, the material contained on the debut collection from the Compton, California, rapper-businessman was positioned by Priority in the same creative category as the work of acclaimed superstars Tracy Chapman and Guns N’ Roses.

Foreshadowing the pro freedom of speech stance Priority Records would take with N.W.A, Ice-T, and Paris, among others, label president Bryan Turner also celebrated his willingness to allow Eazy-E to deliver music detailing what the release calls “the type of drug dealing and violence he was exposed to growing up in L.A.’s Compton ghetto.” Turner added: “What right would I have to censor what he wanted to say?”

It’s also noteworthy that the commercial success of N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton album is tacked on to this press release as a footnote.

Black women also began to get noticed in rap. The second album from Brooklyn’s MC Lyte, Eyes on This, was embraced for its no-nonsense lyrics about love and conflict, while Newark, New Jersey, rapper-singer Queen Latifah delivered largely upbeat and regularly Afrocentric tunes on her debut album, All Hail the Queen.

Similarly, white rappers had a minor breakthrough of sorts with Beastie Boys’ second album, Paul’s Boutique. Produced by former college radio DJs the Dust Brothers, it was Beastie Boys’ first album in three years, and was rife with obscure samples and witty wordplay, and it enjoyed massive critical acclaim. Also, The Cactus Album from 3rd Bass earned credibility and accolades in the black male–dominated rap universe thanks to the New York rap group’s lyricism and material with De La Soul producer Prince Paul and Public Enemy producers Eric “Vietnam” Sadler and brothers Hank and Keith Shocklee.

DELICIOUS VINYL

As gangster rap gained momentum, Los Angeles rap got a pop jolt thanks to Delicious Vinyl. Founded by Los Angeles DJs Michael Ross and Matt Dike, the imprint scored huge commercial and crossover success in 1988 with Tone Lōc’s “Wild Thing” and followed it up a year later with “Funky Cold Medina.” Both of Tone Lōc’s breakthrough singles were cowritten by fellow Delicious Vinyl artist Young MC. In 1989, Young MC scored his own pop hit with “Bust a Move.” These often playful and decidedly ungangster songs sold more than two million copies collectively and set Delicious Vinyl up as a musical foil to the type of music Ice-T, N.W.A, Eazy-E, and Ice Cube were making. The imprint enjoyed subsequent success with Def Jef, the Pharcyde, and Masta Ace Incorporated.

Meanwhile, Los Angeles rap got a decidedly commercial and lighthearted makeover thanks to the success of Tone Lōc’s blockbuster “Wild Thing” and “Funky Cold Medina” singles, as well as Young MC’s smash party track “Bust a Move.” Rap was proving that it was no longer a minor movement, but rather a robust musical genre with many influences by artists emerging from an increasing number of states and from an expanding range of racial and economic backgrounds.

As the rap world continued developing in scope, beginning to reach new and different audiences, Ice Cube began focusing on his solo album. Bolstered by its creative explosion in 1988 and 1989, rap had taken on a heightened sense of purpose coupled with a seething dynamic rage. These changes were thanks, in large part, to Ice Cube’s work on N.W.A’s material, as well as the work of Ice-T, Public Enemy, and Boogie Down Productions. Ice Cube’s insight into contemporary urban distress proved invaluable for the South Central rapper. His profound and incendiary work was rife with rhymes about social injustice and the harsh realities of gang-infested street culture, qualities that had impressed a number of rap industry insiders.

When Ice Cube decided to work on his solo album, he went with members of his new crew, the Lench Mob, to New York to seek out the services of New York producer Sam Sever, best known for his work with 3rd Bass, who recorded for rap industry stalwart Def Jam Recordings. While waiting in the label’s offices for Sever to show, Ice Cube saw Chuck D in the hallway. They had a conversation, which led to Ice Cube’s appearance on “Burn Hollywood Burn,” a cut from Public Enemy’s 1990 Fear of a Black Planet, which also featured Big Daddy Kane. The selection bashed the Hollywood shuffle that the film industry forced black actors, actresses, and creatives to endure by offering them little more than demeaning or stereotypical roles.

THE BOMB SQUAD

Best known for their work with Public Enemy and later Ice Cube, the Bomb Squad (original core members Hank Shocklee, Keith Shocklee, Carlton “Chuck D” Ridenhour, and Eric “Vietnam” Sadler) worked collectively and individually on a gaggle of other projects, including material with Doug E. Fresh and the Get Fresh Crew, Slick Rick, LL Cool J, 3rd Bass, and Bell Biv Devoe. As sampling became prohibitive because of cost and clearance issues, the Bomb Squad evolved with the addition of Gary “G-Wiz” Rinaldo and the departure of the Shocklees and Sadler. Sample-based music was replaced by computers and keyboard-generated sonics.

While in the studio working on “Burn Hollywood Burn,” Ice Cube told the Bomb Squad about his fallout with N.W.A and that he had come to New York to work on his album, a fact Ice Cube said had drawn snickers from N.W.A. “Something in [Hank Shocklee’s] eyes turned on, like, ‘They laughed?’” Ice Cube said. “I said, ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘We’ll do your whole album if you want us to.’”

This exchange produced one of the most noteworthy collaborations in rap history. Given rap’s short history at that time and the concentration of artists in New York, there hadn’t been much collaboration between artists and producers from different cities. LL Cool J’s Bigger and Deffer was an early exception. It was produced by LL Cool J and the L.A. Posse, a crew whose members included DJ Pooh (longtime King Tee collaborator and later Ice Cube collaborator) and Bobby “Bobcat” Erving (a member of Uncle Jamm’s Army).

Just two years earlier, in 1987, producers had been largely unknown entities in the rap world and in the larger music industry. By contrast, when Ice Cube started working on AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted in 1989, Public Enemy was becoming one of music’s most acclaimed groups, thanks in part to their raucous, distinctively assembled production, a kind of aural assault punctuated by hard-hitting percussion, sirens, and political speeches.

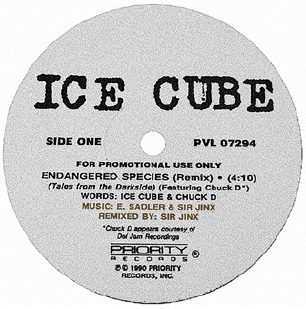

AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted brought the Bomb Squad’s riotous sounds to Ice Cube’s blistering lyrics, while the funk-based production from the Lench Mob member and Dr. Dre’s cousin Sir Jinx gave much of the album a West Coast sonic feeling. The Bomb Squad and Sir Jinx worked in tandem to create a distinctive muscular aural presence by merging two of the most dominant sounds in rap: Public Enemy’s cut-and-paste organized chaos and a funk-driven sensibility via Sir Jinx.

Given his split with N.W.A, there was tremendous pressure on Ice Cube to deliver. With the hype N.W.A had generated, Ice Cube knew that AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted had to feature rhymes and concepts more insightful, provocative, and memorable than the ones from Straight Outta Compton and Eazy-Duz-It. He started with the spelling of the album title. Ice Cube was inspired by popular television program America’s Most Wanted. Debuting in February 1988, the show profiled criminals on the run and encouraged viewers to call into the program toll-free in order to help bring criminals to justice. Ice Cube changed the spelling of America to reflect his opinion of the country during Reaganomics. “Spelling it like that made the record political,” he said, “and not just dismissed as a gangsta record.”

“I thought it was very bold,” said Yo-Yo, Ice Cube’s female protégé who made her debut on AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted. “America was in a crisis at that time. We were just getting out of the batterram, with the police coming into people’s homes using this military device in the urban community, from [N.W.A] having all that controversy with ‘Fuck tha Police,’ even [Ice Cube] leaving N.W.A.”

“America was in a crisis at that time. We were just getting out of the batterram, with the police coming into people’s homes . . .”

YO-YO

Lyrically, Ice Cube leaned on a lesson he’d learned from Dr. Dre while working with him at Ruthless Records: Either shock people or make them laugh. He stuck to that winning formula, building upon it and merging the imaginative storytelling abilities of Slick Rick and the XXX-rated raunch of Too $hort with the political insight of Public Enemy’s Chuck D in a way that removed any doubt about his artistic acumen.

It was hailed as a masterpiece, and with good reason. Ice Cube put his artistry on full display throughout AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted. The album starts off with “Better Off Dead,” essentially a skit in which Ice Cube gets executed via the electric chair while in prison. It then kicks into high gear with the first bona fide song, “The Nigga Ya Love to Hate.” After opening the first verse saying that he’s tired of being treated like a stepchild, he goes on to blast black people who give only a token allegiance to Africanism. Then he takes aim at critics trying to silence his brand of rap.

They say we promote gangs and drugs / You wanna sweep a nigga like me up under the rug / Kicking shit called street knowledge / Why more niggas in the pen than in college? / Because of that line I might be your cellmate / That’s from the nigga ya love to hate

For the “The Nigga Ya Love to Hate” hook, Ice Cube took the unorthodox step of having a chorus of people chant “Fuck you, Ice Cube!” followed by a male voice accusing him of not doing anything positive for the black community. After the second verse, the “Fuck you, Ice Cube!” chorus returns and is followed by an animated woman berating Ice Cube for calling women “bitches” and proclaiming that she does not fit the bill.

It was an unprecedented move. True, UTFO let women diss them during the “Roxanne, Roxanne” era in the mideighties and N.W.A and Too $hort featured women checking them on their songs in the late eighties, but male-female tension in the hypermasculine rap world was to be expected, especially when it was being framed by alpha males who typically got the best of the women with whom they were arguing.

What Ice Cube did, on the other hand, was shocking, strident, and extraordinary. To be the best rapper from the most acclaimed gangster rap group and to have a woman diss you and to diss yourself on your own song by having a chorus of people scream “Fuck you, Ice Cube!” was remarkable. By dissing himself on record before N.W.A or anyone else could, Ice Cube was letting the world know that he was aware of the doubters eager to take shots at his solo career and his departure from rap’s most significant group. It was a revolutionary move that rallied rap listeners behind Ice Cube’s music.

Not everyone thought Ice Cube should be disparaging himself on his own song, though. “That was a big argument between us, about should somebody say ‘fuck you’ to themselves on their own record,” Ice Cube said. “I remember [Sir] Jinx not really wanting to do that. He had his reasons, because he was in the inner thing with me and N.W.A. [Dr.] Dre is his cousin. He didn’t think it was cool, at the time, to do that, and I was like, ‘Man, it’s the perfect time.’”

This was the first song most people heard from Ice Cube’s solo album. The California rapper came out swinging, verbally dismissing his detractors, mocking America’s bicentennial, and calling out fake black nationalists and sham black cultural fixtures. Before the song concludes, Ice Cube also disses Soul Train and The Arsenio Hall Show, two vaunted staples of black television programming. Cultural icons took Ice Cube’s swing soundly on the chin.

SIR JINX

The cousin of Dr. Dre, Sir Jinx introduced Ice Cube to Dr. Dre and became integral to the early portion of Ice Cube’s career, helping produce and shape the sound of Ice Cube’s debut album, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted. Sir Jinx continued working with Ice Cube for several years and also collaborated extensively with Yo-Yo, WC and the Maad Circle, Kool G Rap & DJ Polo, and Xzibit, among others.

As he had done while in N.W.A, Ice Cube was eager to examine and highlight the strife between racial and social classes. “In my music, when we talk about race, I give it to everybody,” Ice Cube said. “Nobody really gets away clean—not black people, women, Mexicans, whites, Koreans. All races get it, because all races deserve it [because of] what’s going on.”

Although he was sometimes painted as anti–law enforcement, antiwhite, and anti-establishment, Ice Cube was also anti–police brutality, antiracism, and anti-oppression. This distinction may have been lost on some, but it endeared him to both black and white fans, who embraced Ice Cube as a premier rap talent who presented the positive and the negative, the celebratory and the abhorrent, all in one.

Case in point: “A Gangsta’s Fairytale,” an explicit reimagining of a number of classic fairy tales that Ice Cube had originally written for Eazy-E and repurposed for himself. In the song’s intro, a kid asks him to stop rapping about “the bitches and the niggas” and implores him to rap about the kids. Ice Cube obliges. But instead of the G-rated, good-natured stories of Jack and Jill, Cinderella, and Little Red Riding Hood, these same characters were involved in drug use, gangbanging, drive-by shootings, and prostitution, among other illegal activities. Consider the X-rated revision of the Jack and Jill adventure:

Down on Sesame Street, the dope spot / There he saw the lady who lived in a shoe / Sold dope out the front, in the back, marijuana grew

“A Gangsta’s Fairytale” producer Eric “Vietnam” Sadler recalls loving the song, even though his wife took objection as soon as the song’s intro was finished. “After the part where the kid starts talking about ‘the kids,’ my wife said, ‘Oh, you’re going to hell for that one,’” Sadler said with a laugh. “And I said, ‘Yeah, it kinda feels like that.’”

For his part, Ice Cube said that the blend of gangsterism and humor he injects into his music is similar to the balance every person struggles with. “We’ve all got a dark side and a light side. I don’t know too many people that don’t love to laugh, and I don’t know too many people that don’t have those places in themselves. It’s a crazy combination that works, like chicken and waffles. When you look at it from the outside, it isn’t supposed to work. But when you put it together, it works.”

Unfortunately, the social and economic conditions that inspired Ice Cube to write “Endangered Species (Tales from the Darkside),” a collaboration with Public Enemy rapper Chuck D, remained rampant. The cut opens with a faux news broadcast in which the female reporter notes that young black teens have been added to the endangered species list. No efforts, she notes, have been made to preserve the black people because, as one official said, “They make good game.”

As he had done on N.W.A’s “Fuck tha Police,” Ice Cube bemoaned police brutality against blacks on this track. One of his lines played off the Los Angeles Police Department’s motto, “To protect and to serve.”

They kill ten of me to get the job correct / To serve, protect, and break a nigga’s neck

Ice Cube looked at the black existence in America as a rigged game, complete with temptation at virtually every turn. “I feel it is a trap,” he said. “I feel it’s just all geared to get us drugged out, in the penitentiary, to get us shot—to kill you or to lock you up, to cause misery. The ghetto is a nigga trap. They make it look easier, but as soon as you take the cheese, here they come and your ass is locked up. It’s bait. There’s bait out there for you.”

The bait, all too often, resulted in a stay behind bars, as evidenced by the staggering incarceration rates for young black men in America. A 2013 report from the Sentencing Project stated that one in three black men will go to prison at some point in his life. Ice Cube references being incarcerated in several AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted songs, including “Once Upon a Time in the Projects.” Here, he goes to a girl’s house with the hopes of taking her out. But what should have been a routine stop goes horribly wrong as the girl’s mother ends up being a cocaine dealer and the house gets raided as Ice Cube’s character is about to leave. Although his character was innocent and beats the case, he still spends two weeks behind bars.

Ice Cube’s character in “Once Upon a Time in the Projects” realizes he has gotten himself into a bad situation and tries to vacate the premises. His character on AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted’s title track is a criminal but still meets the same fate. In that song, he puts himself in a bad situation by robbing a white man. After he sees himself on the news, his character ends up in the penitentiary, noting that police only pursued him once he robbed a white man. It was the type of imprecise justice—laws being enforced arbitrarily, but always if the victim is a white person—that Ice Cube railed against in his music and warned his listeners about.

“I’ve always tried to do songs where I want motherfuckers to think before they end up in the pen,” Ice Cube said. “I want them to put it all together before that happens to them because those motherfuckers will keep you for years. It ain’t no bullshit. They ain’t playing. Some stupid little shit will fuck around and have you gone for years. If I can get people to think about that . . . I want people to think. It’s easier to think about legal ways to make money than it is [to think about] illegal ways. There’s more legal ways to make money out here than there is illegal ways to make money.”

On AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, Ice Cube also wanted to show that he viewed women as more than just a temptation or trouble. He was cognizant that “I Ain’t tha 1” from N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton and his N.W.A single “A Bitch Iz A Bitch”—explicit songs where Ice Cube illustrated that he wasn’t going to cater to money-hungry females, regardless of how attractive they might be—had created an antiwoman identity around his raps. He saw this as an opportunity. With that in mind, he recorded “It’s a Man’s World,” on which he introduced his Los Angeles–based female protégé Yo-Yo and gave her the platform to respond to his assertion at the top of the song that women were only good for fulfilling his sexual needs. Yo-Yo took full advantage:

Yo-Yo’s not a ho or a whore / And if that’s what you’re here for / Exit through the door

GANGSTA BOO’S TOP FEMALE GANGSTER RAPPERS

Gangsta Boo rose to prominence in the mid-1990s as a member of Three 6 Mafia. The Queen of Memphis names her favorite female gangster rappers.

Bo$$. She had a bob. She used to a wear a vest and Locs. She had the record “Deeper,” but I was a little young back then.

The Lady Of Rage. First of all, I thought her afro puffs were sick as shit. She was the female of the West Coast at that time rockin’ out with all those dudes, the Death Row shit, like, “Who the fuck is this?” She was a taller, bigger chick snapping like that with two fuckin’ afro puffs in her hair. That’s bad-ass, and she was killing it on all the tracks that she got on, so I just respected that about her. That name, too, The Lady Of Rage, like, “I’m the lady of this fuckin’ rage, this fuckin’ fire. I’m the lady of this shit. The anger, the rage, the destruction, it’s all me. Come fuck with me if you want to, and get your ass fucked up.”

Gangsta Boo. I’m the first female rapper that made it out of Memphis and that was with a multiplatinum group. I stood out not even trying to stand out. I listen to my old stuff and be like, ‘Damn, dude, I was like fourteen years old snapping like that.’ The raps that I wrote when I was fourteen is how bitches sound now. That’s just amazing to me. So, that’s the good in me. I gave a lot of the youth their sound.

Mia X. Mia was an inspiration. She was the mother of Southern gangster rap. She was much older than me, so when I did come out doing my thang, I show love to the motherfuckas that’s older than me, that got a little more experience. She reminded me of me. She was the only female, before [Master] P started signing other women, in a clique full of dudes as gangster as No Limit. It was very inspiring to see a female rip it with a whole bunch of dudes with no problem, and killin’ half of ‘em on their own tracks. That’s gangster.

La Chat. To me, La Chat is like ratchet, the ratchet everybody is being now. She was before her time. She’s got gold teeth, and those are her permanent gold teeth. It’s something about permanent gold teeth on females I think is the most gangster, hoodish shit ever. And, she’s not doing it for a gimmick. That’s who she is, and I think that’s dope.

Gangsta Boo celebrates female rappers.

Yo-Yo parlayed her powerful performance on Ice Cube’s “It’s a Man’s World” into a successful career that jumpstarted with 1991’s Make Way for the Motherlode and its singles “Stompin’ to tha 90’s” and “You Can’t Play with My Yo-Yo,” the latter of which featured Ice Cube. Even though she was affiliated with Ice Cube and was from Los Angeles, she was not a gangster rapper, a reality that took on additional meaning with the emergence of female gangster rapper Bo$$ in 1993.

“At the beginning, I thought it was just like a fantasy until they started blaspheming Bo$$ for not being a real gangster chick,” Yo-Yo said. “Then I went into a shell. I started hiding, like ‘Oh my God. I’m not really a gangster chick, and here are these journalists calling me a gangster,’ so I went into hiding. I was like, ‘Oh, god. I have to perpetrate who I really was.’ It was hard for me to say that I really didn’t live a gangster life.”

In addition to impacting her personal life, the gangster rap stigma affected her musical trajectory.

“Creatively, it opened my eyes and it started letting me see what the real world was all about and how hip-hop was really affecting the community,” she said. “All those years that I told journalists I wasn’t a role model, I started thinking, ‘Well maybe I am.’ I never knew that lyrics had power, and I started realizing how powerful lyrics in hip-hop was. I was introduced to a new reality. I was realizing that there were ghettos in every community. I was realizing that dark skin[ned blacks] didn’t like light skin[ned blacks], and that society was pinning brown against the black. I started seeing that the political figures had a monetary gain and that people of power had influence [in that rift].”

It’s noteworthy that the hypermasculine, alpha-male Ice Cube let a female rapper diss him on his own album. “I felt like if we did a song where we were battling—she was talking shit about me, I was talking shit about her—that she would be looked at as a top-tier rapper, like Queen Latifah or Salt-N-Pepa,” Ice Cube said. “I didn’t want her to have to struggle from the bottom up.”

Pomona, California, rapper, singer, G-Funk practitioner, and former Ruthless Records recording artist Kokane also believes Ice Cube looked at Eazy-E’s business blueprint when selecting Yo-Yo.

“Ice Cube knew why there was a Ruthless Records in the first place,” Kokane said. “J.J. Fad was a woman group that actually broke in the door for Straight Outta Compton. From that aspect, he was already seasoned, like ‘I’m going to get me a tight-ass female, and she’s gonna be dope like me,’ and he found the right fit. Ice Cube knew that Yo-Yo could identify with women [that are] in the hood, the women [that have] got their own shit. It was empowerment for women, especially women of color.”

By dissing himself on “The Nigga Ya Love to Hate,” partnering with Chuck D on “Endangered Species (Tales from the Darkside),” reworking nursery rhymes into XXX-rated adventures on “A Gangsta’s Fairytale,” introducing his new crew on “Rollin’ Wit the Lench Mob,” and letting a female insult him on “It’s a Man’s World,” Ice Cube pulled off a remarkable feat. He left rap’s hottest group and became, arguably, the best and most important solo rapper of the time. Ice Cube wanted to make music his way, regardless of the consequences.

“I’m pretty sure it’s turned some people off,” he said. “What I’m saying is being recorded. I don’t take that lightly. I take that as an opportunity because that’s going to be here when I’m gone. So I feel like I’ve got to speak on that, or really, what am I rapping about? If I’m not rapping about shit that affects us all, what really am I rapping about? I say what I feel. It’s that simple. I say what I feel. I can gain a fan and lose a fan in the same verse. I say what I gotta say and let the chips fall where they may.”

Ice Cube bet on himself and was rewarded with a platinum plaque and the start of one of the most successful careers in music history, one that melded the gangster rap world of N.W.A with the political work of Public Enemy. AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted offered a brilliant balance of street-centered insight and big-picture commentary accented by a masterful blend of violence and humor, reverence and rage. It was also a manifesto of a black man standing on his own by escaping America’s oppressive cultural system through his art and his beliefs—as well as Ice Cube’s exit from Eazy-E’s Ruthless Records.

“You could tell that N.W.A had not made Ice Cube,” DJ Quik said.

Stylistically, Ice Cube was backed by riotous music. More than any other rap album before it, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted was a groundbreaking mélange of East and West Coast sonics that moved the genre into new aural territory and showed what rap could be when it combined sounds from different regions.

AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted also put N.W.A on notice: Ice Cube could stand on his own and excel while doing so.

“He was a strong-minded, powerful African American dude,” the D.O.C. said. “He walked out holding his nuts and he believed in what he was doing. It wasn’t just for blowing his horn, or riding any particular bandwagon, or doing something so he could label it this or label it that. That’s how he felt, and I was 1,000 percent with it.”

Even as Ice Cube’s solo career was gaining steam, gangster rap was about to get a grisly makeover, thanks to a group of self-proclaimed madmen.