The Geto Boys went from independent to infamous.

IN 1989, THE BLEAK REALITY OF AMERICAN INNER-CITY LIFE WAS BECOMING MORE WELL-KNOWN BY THE REST OF AMERICA.

In August, the Federal Bureau of Investigation said that the number of violent crimes reported nationwide in 1988 was 1.56 million, an increase of 5.5 percent from the previous year and an all-time high. This represented increases in aggravated assaults, robberies, murders, and rapes. Nearly half of the 18,269 murder victims in 1988 were black, meaning that blacks were being killed at a rate that was more than four times what it should have been relative to their percentage of the US population.

These sobering statistics helped fuel the steady growth of gangster rap. As Ice-T, N.W.A, and Ice Cube were changing the direction of rap in Los Angeles, another rap entrepreneur was making moves in Houston. James Prince (also known as J. Prince, Lil’ J, or J), a used-car salesman, had founded Rap-A-Lot Records in 1986 with the intention of becoming a major player in the emerging rap world.

TIMELINE OF RAP

1990

Key Rap Releases

1. A Tribe Called Quest’s People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm album

2. Vanilla Ice’s “Ice Ice Baby” single

3. Digital Underground’s “The Humpty Dance” single

US President

George H.W. Bush

Something Else

Nelson Mandela was released after twenty-seven years behind bars.

The Texas businessman’s debut group proved to be his most significant. Originally called the Ghetto Boys, Rap-A-Lot Records’ flagship crew initially consisted of rappers Raheem, K9 (Sir Rap-A-Lot), and Sire Juke Box. Scarface, who had yet to join the outfit, remembers their first release, “Car Freak,” as being one of Houston’s first rap releases.

Although gangster rap from Los Angeles, in particular, was steadily becoming more prominent, the majority of rap was still coming from New York, its birthplace. “Everything else was coming from New York, and the stuff that was coming out of Houston sounded so far behind, it was like Cracker Jack rap—just super-simple rhymes not saying shit that [could] have been printed on the back of a pack of some kiddie snacks,” Scarface said. “‘Car Freak’ wasn’t crazy, but it gave J something to build on.”

A savvy businessman with a talent for marketing, J. Prince was modeling his fledgling imprint on two of rap’s premier talents of the era: LL Cool J and Run-DMC. Raheem, who left the Ghetto Boys after “Car Freak” to embark upon a solo career, was the LL Cool J equivalent, even going so far as to appear on the cover of his The Vigilante album in 1988 wearing a red Kangol hat, LL Cool J’s signature choice of headgear at the time.

On their debut album, 1988’s Making Trouble, the Ghetto Boys (now composed of Sire Juke Box, Prince Johnny C, and DJ Ready Red, and featuring dancer Bushwick Bill) rapped in a bombastic tag-team style similar to the one Run-DMC employed. Musically, the production on the early Ghetto Boys material was often bare-bones and percussion-driven with a smattering of rock guitars thrown into the mix. Lyrically, the rhymes were neither distinctive nor memorable. AllMusic called the album “clunky and derivative.”

Thus, rather than making a name for itself by bringing a new perspective and energy to rap, it was as if Rap-A-Lot Records was merely making its own versions of material patterned after that of rappers who were already successful. Raheem, for his part, was talented and enjoyed regional success with his singles “Dance Floor” and “The Vigilante,” but he didn’t break through as a solo artist, at least in part because his sound wasn’t particularly distinctive and he was viewed by those outside of the region as an LL Cool J knockoff.

But J. Prince had a plan for the Ghetto Boys. In 1972, the funk and soul band War had released the album The World Is a Ghetto. J. Prince, embracing a belief similar to the one presented by the album’s title, determined that kids in the ghetto needed a group to represent them, to talk how they talked, to articulate what they felt. These kids were downtrodden, and J. Prince was looking for a crew of artists to execute his vision.

SETTING THE SCENE (AS OF 1990)

PHYSICAL LOCATION: Houston

POPULATION: 1.6 million

BLACK PEOPLE LIVING IN HOUSTON: 448,000

HISPANIC OR LATINO PEOPLE LIVING IN HOUSTON: 451,000

WHITE PEOPLE LIVING IN HOUSTON: 662,000

ASIAN PEOPLE LIVING IN HOUSTON: 67,000

OTHER: 3,000

MURDER RATE AMONG MAJOR CITIES: No. 6

LOCAL POLITICS: Houston hosted the sixteenth annual G7 Summit. The leaders of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States attended the forum. Topics discussed at the event included narcotics, the environment, and Third World debt.

POLICE: In 1990, Elizabeth Watson became Houston’s first female police chief.

Not believing the existing members of the Ghetto Boys could implement his concept, J. Prince revamped the group’s lineup. Bushwick Bill, who has dwarfism and who had been a Ghetto Boys dancer, was already in the fold, and J. Prince signed Golden Gloves boxer-rapper Willie D after he won a string of rap battles at Houston’s Rhinestone Wrangler nightclub. Scarface, who originally recorded as DJ Akshen and changed his name in honor of the title character of the 1983 film starring Al Pacino, earned a spot at the label after battling Ghetto Boys member K9, who happened to be J. Prince’s brother. After losing to Scarface, K9 was no longer in his brother’s flagship group. With holdover DJ Ready Red, the new lineup of the Ghetto Boys was set: rappers Scarface, Willie D, and Bush-wick Bill and producer DJ Ready Red.

After the success of Schoolly D, Ice-T, Boogie Down Productions, and N.W.A, all of whom had sold hundreds of thousands of records rife with talk of guns, illicit sex, and violence, the underground rap world was ravenous for more. Given that no Houston rap act had made either a critical or a commercial dent in the rap world (and because of the bland fare on their debut album), the Ghetto Boys was an unlikely group to push gangster rap forward. But where Making Trouble contained mostly typical rap bluster on such songs as “You Ain’t Nothin’” and “I Run This,” and featured relatively tame lyrics about robbery on the title track, the new cast of the Ghetto Boys infused extreme levels of violence, paranoia, sex, drugs, and profanity into their next project, 1989’s Grip It! On That Other Level.

SCARFACE’S INFLUENCE ON GANGSTER RAP

Scarface may have had more effect on rap than any other film. The 1983 movie starring Al Pacino traces Cuban immigrant Tony Montana’s rise from a petty drug dealer to kingpin status. Montana’s rise to power, his code of ethics, his street savvy, and his memorable lines appealed to members of the rap world, who felt they could identify with the character’s hopes, dreams, ambitions, and struggles. Albums from the Geto Boys, Scarface, and others liberally used Scarface’s theme music and score, and made several of Montana’s catchphrases (“Say hello to my little friend” and “All I have in this world is my balls and my word, and I don’t break them for no one”) famous by incorporating them into several songs and choruses.

Whereas much of the music and lyrics on Making Trouble is quaint, Grip It! On That Other Level was anything but. The album’s sonics were forceful and the rhymes ribald, rambunctious, and rancorous. Grip It! On That Other Level also featured sound bites from Al Pacino’s portrayal of crime lord Tony Montana in Scarface woven into the fabric of several songs throughout the album, mainly his yelling “Fuck you, man” and “I’ll bury those cockroaches” in his faux Cuban accent.

On “Do It Like a G.O.,” Grip It! On That Other Level’s opening track, J. Prince (going as Lil’ J) appears on a conference call with Willie D and Scarface and laments that he’s tired of being disrespected as a black businessman and that he won’t sell out. J. Prince then orders the group to take it to “the other level of the game.”

The Ghetto Boys did not disappoint. On “Do It Like a G.O.,” Willie D boldly took the unprecedented step of dissing the rap industry elite, all of whom were located in New York at the time:

The East Coast ain’t playin’ our songs / I wanna know what the hell’s goin’ on . . . Everybody know New York is where it began / So let the ego shit end

Willie D’s comments would be akin to a child talking back to their parents for the first time. All the emerging labels putting out rap music (Def Jam Recordings, Jive Records, Tommy Boy Music, Profile Records, Select Records, Next Plateau Records, and Cold Chillin’ Records, as well as Sleeping Bag Records and its sublabel Fresh Records) were located in New York, save for the rising Los Angeles–based Priority Records. The men running rap labels had been largely content with signing and working with local talent up to this point. The rap business had also been fighting the larger music industry to get exposure in the mainstream press and on the radio, with little success. Things were changing, though, thanks to the fledgling Yo! MTV Raps.

The motto of the prominent New York–based hip-hop awareness organization Universal Zulu Nation was “peace, unity, love, and having fun.” But with rappers starting to sell hundreds of thousands of singles and albums, and the exposure Yo! MTV Raps offered, Willie D was speaking for every American city that wanted in to the rap game. They felt they had been marginalized by being denied a legitimate opportunity due to rap’s xenophobic nature. Essentially, if you weren’t from New York, you didn’t matter to the New York rap crowd, which drove much of the national market.

Thus, it was a bold, risky move for Rap-A-Lot to stick its neck out in the ultra-insular rap world, which had been slow to develop artists of note hailing from beyond New York’s five boroughs during its first decade on record, by calling them on it.

In one of his verses on the song, Scarface announced one of the Ghetto Boys’ roadblocks:

Black radio is being disowned / Not by the other race, but its own / A lot of bullshit records make hits / Because the radio is all about politics

In general, rap had enjoyed little radio exposure up to 1989, other than Los Angeles rap radio station KDAY and specialty rap shows in major markets such as New York and Philadelphia. That didn’t appear to matter to the Ghetto Boys. To paraphrase President George W. Bush, a fellow Texan, more than a decade later, the Ghetto Boys and Rap-A-Lot Records had adopted the mindset that either you were with them, or you were against them—that is, with the enemy. And the Ghetto Boys’ enemy was anyone who didn’t support rap or, more particularly, didn’t support the Ghetto Boys.

“DO IT LIKE A G.O.”

Two main versions of the song “Do It Like a G.O.” were released by Rap-A-Lot Records in 1989. One appears on the Ghetto Boys’ Grip It! On That Other Level album with raps from Willie D, Scarface, Bushwick Bill, and DJ Ready Red. The other version of the song was included on Willie D’s Controversy album, which was also released in 1989 and features Sire Juke Box and Prince Johnny C rapping virtually the same lyrics as the ones Scarface and Bushwick Bill use on the other version of the cut.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a wave of Southern, black-owned record companies emerged, including Luther Campbell’s Luke Skyywalker in Miami and James “J. Prince’s” Rap-A-Lot Records in Houston. Their success paved the way for Tony Draper’s Suave House Records in Houston; Master P’s No Limit Records, first in California and then in Louisiana; and Three 6 Mafia’s Hypnotize Minds. Each imprint released gangster rap material, though they didn’t all focus exclusively on the genre. What each company did do, though, was bring a street-based way of operating to the music business.

“We all have a street element because we come from a street element,” said Tony Draper, whose company released gold and platinum projects from 8Ball & MJG. “We were all already of the mindset of spending our own, owning our own. So by the time we did a deal with any major label, we had already sold hundreds of thousands of records through our one-stop distributors. So, when we’d come to New York and see the people we used to admire on TV and they had nothing – no money, no ownership of anything – we were like, ‘Yo. That’s not what it is. That was never impressive to us.’ I think that we had a different mindset coming from a street element, but being educated enough to convert a street element into a real form of business.”

The power of “Do It Like a G.O.” continued as Willie D claimed that blacks were being taken advantage of in the drug game and Bushwick Bill warned that the street life resulted in either death or incarceration—the latter situation also typically resulted in your woman quickly and happily finding another man. For his part, Scarface detailed how racism impacted the school system:

Whites get more funds from the state / And this is why minorities learn so late

This institutional and financial racism has a trickle-down effect, one not lost on Bushwick Bill during his take on the evolution of black people in America:

Our ancestors were killed at will / Bought and sold like a used automobile / We fought so blacks could exist / Now we’re killin’ one another, ain’t that a bitch

On “Do It Like a G.O.,” the newly revamped Ghetto Boys demonstrated that their aggressiveness knew no limits and that the group was more than willing to take on any opponent, whether it be the rap gatekeepers, black radio stations, the school system, the black urban community, or the white power structure.

Rap-A-Lot Records owner James Prince also wanted to make sure his presence was felt on “Do It Like a G.O.” In the cut’s intro, Prince mentioned the frustration he faced as a black businessman trying to make his mark in the rap world. As the song concludes, he takes a phone call from the president of White Owned Records, who gives him two choices. One: Keep your boys quiet or else. The other: Keep a five percent stake in his own company and become rich in fifteen years, but White Owned Records would own ninety-five percent of Rap-A-Lot. J. Prince’s response: “Man, fuck you.”

For the disenfranchised black audience J. Prince was targeting, cursing out a white man offering him a substandard business deal established him as a sort of mythical figure, a businessman ready to go to war with the powers that be for what he believed in.

“It was easy to relate to because their stories mirrored our stories at that same time,” DJ Quik said. “They made it cool to be from Down South.”

Much of the rest of Grip It! On That Other Level set J. Prince and the Ghetto Boys up for both success and war. The album’s second song, “Gangster of Love,” was one of the most sexually explicit rap songs ever released at that point. Prior to “Gangster of Love,” Too $hort released songs such as “The Bitch Sucks Dick,” “Blow Job Betty,” and “Freaky Tales,” while the 2 Live Crew built their brand on such selections as “We Want Some Pussy,” “Do Wah Diddy,” and “One and One.”

Schoolly D (“Mr. Big Dick”) and Ice-T (“Girls L.G.B.N.A.F.”) also had overtly sexual songs that graphically discussed sex and/or sex acts, but the Ghetto Boys ratcheted up the stakes with “Gangster of Love.” In the first verse, Willie D rapped that he would kick a girl’s ass if she messed with him, while Bushwick Bill expressed his affinity for having sex with his girl’s friend and watching them have sex with each other. He also boasted that he would readily have sex with his girlfriend’s mother if she gave him the opportunity.

RAP-A-LOT RECORDS’ MOST GRUESOME ALBUMS AND SONGS

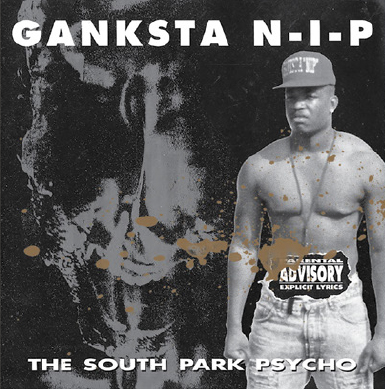

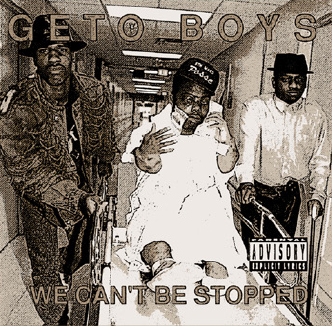

The Geto Boys and fellow Rap-A-Lot Records act Ganksta N-I-P have released some of rap’s most grisly material. In 1991, Ganksta N-I-P wrote the song “Chuckie” for Bushwick Bill. The song appears on the Geto Boys’ 1991 album, We Can’t Be Stopped, and features Bushwick Bill imagining himself as the horror movie character Chuckie and slicing up someone’s nieces into eighty-eight pieces and putting severed heads with knives in them into mailboxes. “It scared the bejesus out of me,” DJ Quik said. For his part, Ganksta N-I-P pioneered the horrorcore rap subgenre with his The South Park Psycho album in 1992. It features the Houston rapper detailing his violent, murderous, and sometimes cannibalistic ways.

But what made the Ghetto Boys different from their sex rap predecessors was their willingness to include violence as a consequence for sexual disobedience or for lying about being pregnant. Willie D rapped about Ms. P, a woman who lied and said he had gotten her pregnant. After saying that he drugged “her little ass like a motherfucking horse,” he upped the ante even more.

I’ll kick a bitch smack dead in the ass if she ever say we / Made a kid when I make it / I’ll grab her by her motherfucking neck and try to break it / ’Cause I know I wore a fucking glove

Willie D continued his verbal assault against “no-good women” on “Let a Ho Be a Ho.” With the sound of a cash register ringing throughout the guitar-accented track, Willie D rapped about how men fall in love with women who have sex with as many men as possible. In the fourth verse, he rapped about having sex with a woman, arranging a threesome with a second woman, and then realizing that they stole his wallet once he drops them off. Rather than get upset, though, he laughs it off because he is able to have sex with the women whenever he likes. He also made a point to say that he’d never buy a woman jewelry, makeup, or food, among other things.

The rap community had taken issue with LL Cool J’s 1987 song “I Need Love,” which was the first popular rap love song. A sizable segment of the rap world was turned off by what it perceived to be LL Cool J’s sellout attempt to appeal to women with a song it deemed soft, especially after he had gone to such lengths to prove his status as a hardcore rapper. By contrast, two years later, the Ghetto Boys were making antilove songs. They were promoting a combination of sex and violence in ways that separated them from other gangster rappers.

The menacing music wasn’t limited to just a few other selections from Grip It! On That Other Level. The album also featured Willie D and Bushwick Bill rapping about beating up anyone (including women) who didn’t support the Ghetto Boys (“Read These Nikes”), Bushwick Bill claiming that his dwarfism would not impede his ability to “fuck you up like a goddamn accident” (“Size Ain’t Shit”), and Scarface relaying a story about how he killed twenty men who tried to ambush him and a cop who tried to stop his escape (“Life in the Fast Lane”).

The album’s final cut, however, took the violence to a grisly place. The macabre “Mind of a Lunatic” featured Bushwick Bill, Scarface, and Willie D rapping about their homicidal tendencies and their respective bloodlusts. The song unfolded more like a horror movie than either the shoot-outs of N.W.A’s most brazen moments or even the rest of Grip It! On That Other Level had.

Scarface, Bushwick Bill, and Willie D are the core members of the Geto Boys, but none of them appear on all of the group’s albums. Here’s a look at the many incarnations of the Geto Boys.

Making Trouble (1988). Members: Sire Juke Box, Prince Johnny C, and DJ Ready Red

Grip It! On That Other Level (1989). Members: Scarface, Willie D, Bushwick Bill, and DJ Ready Red

The Geto Boys (1990). Members: Scarface, Willie D, Bushwick Bill, and DJ Ready Red

We Can’t Be Stopped (1991). Members: Scarface, Willie D, and Bushwick Bill

Till Death Do Us Part (1993). Members: Scarface, Bushwick Bill, and Big Mike

The Resurrection (1996). Members: Scarface, Willie D, Bushwick Bill

Da Good da Bad & da Ugly (1998). Members: Scarface and Willie D

The Foundation (2005). Members: Scarface, Willie D, and Bushwick Bill

RAP-A-LOT RECORDS’ OTHER NOTEWORTHY ACTS

Convicts. The duo’s self-titled 1991 album would be their only LP, but Big Mike later became a member of the Geto Boys and a gold-certified solo artist, while Mr. 3-2 released solo material and formed the group Blac Monks.

Big Mike. After one album with the Geto Boys, Big Mike became a solo rap star, releasing his Somethin’ Serious in 1994.

CJ Mac. Going as Mad CJ Mac at the time, the rugged gangster rapper gave the imprint a Los Angeles presence with his True Game album in 1995.

Do or Die. The smooth-flowing, tongue-twisting Chicago trio of Belo (aka Belo Zero), N.A.R.D., and AK released a string of platinum and gold albums starting with their 1996 single “Po Pimp” from their Picture This album. The group also gave the imprint a foothold in the Midwest.

Devin the Dude. A member of Rap-A-Lot group Odd Squad, Devin the Dude is a pioneering blues rapper whose whimsical, self-deprecating rhymes are among the genre’s funniest. Devin the Dude later collaborated with Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, 8Ball, Nas, OutKast’s André 3000, Lil Wayne, and others.

On the two opening verses of “Mind of a Lunatic,” Bushwick Bill added a new wrinkle to murder on a rap record. He started the song by rapping that he’s paranoid, sweating, and craving sex. Then his thoughts turn murderous.

The sight of blood excites me, shoot you in the head / Sit down, and watch you bleed to death / I hear the sound of your last breath

During the rest of the verse, Bushwick Bill returns to reality but has flashes of Jason, the killer from the Friday the 13th horror film franchise.

In the second verse, Bushwick Bill acts on his thoughts:

Looking through her window, now my body is warm / She’s naked, and I’m a peeping Tom / Her body’s beautiful, so I’m thinking rape / Shouldn’t have had her curtains open, see that’s her fate

He then raps about snatching her as she leaves her house, dragging her back in the house, raping her at knifepoint, and then killing her. As the police arrive, his verse ends, leaving the aftermath of his actions a mystery.

But with his verses on “Mind of a Lunatic,” Bushwick Bill took rap to a new place. His crime was not a response to oppression, racism, a slight, a drug deal gone bad, or a gang problem. He made killing impersonal, something he was compelled to do. It was because he was a self-proclaimed lunatic. The subsequent verses from Scarface and Willie D were brazen, but far less savage than those of Bushwick Bill.

Grip It! On That Other Level was produced by DJ Ready Red, Doug King, J. Smith, John Bido, and Prince Johnny C. Unlike the uninspired beats on much of Making Trouble, the sonics on Grip It! On That Other Level accented and enhanced the words of the Ghetto Boys. “Do It Like a G.O.” sizzled with aggressive percussion, while the rugged scratching on “Size Ain’t Shit” added a rough texture to Bushwick Bill’s threats. The ominous horns and guitar on “Mind of a Lunatic” accentuated the tortured rhymes of Bushwick Bill, Scarface, and Willie D.

As Grip It! On That Other Level gained traction in the South and Midwest through influential mom-and-pop retailers, it also earned an important fan. Producer Rick Rubin became enamored with the album. Rubin had partnered with Russell Simmons for Def Jam Recordings, which the pair launched from Rubin’s New York University dorm room in 1984. During the next several years, Rubin produced material from many of rap’s biggest artists, including Run-DMC, LL Cool J, and Beastie Boys.

After establishing himself as a premier producer and rock and rap talent scout, Rubin left Def Jam in 1988 over creative differences, moved to Los Angeles, and launched his Def American Recordings with major label Geffen Records. Rubin worked out a deal with J. Prince to make the newly rechristened group the Geto Boys the first rap faction at Rubin’s new company.

Given that Grip It! On That Other Level had only been distributed independently through J. Prince’s channels, Rubin and J. Prince decided to revamp the album rather than record an entirely new project. Rubin kept ten Grip It! On That Other Level songs for what would be The Geto Boys album. He had the Geto Boys rewrite and rerecord some of their verses and changed the music on some of the tracks. They also dropped the songs “Seek and Destroy” and “No Sell Out” from the album while adding “F#@* ’Em,” which opened the album in spectacularly controversial fashion, taking aim at people who doubted the group’s staying power or their willingness to push lyrical boundaries. In short, they targeted anyone they thought was against their kind of rap.

The real challenge, though, came with “Mind of a Lunatic,” which had gone from ending Grip It! On That Other Level to prime placement as track three on The Geto Boys. The song also became more gruesome thanks to reworked lyrics and to new, more menacing deliveries from Bushwick Bill, Scarface, and Willie D. Bushwick Bill was now virtually screaming his verses, making his new lyrics all the more frightening.

She begged me not to kill her, I gave her a rose / Then slit her throat and watched her shake till her eyes closed / Had sex with the corpse before I left her / And drew my name on the wall like Helter Skelter

The new lyrics evoked the image of the Manson Family’s crime and murder spree in the sixties, in which leader Charles Manson envisioned an impending apocalypse he called “Helter Skelter.” The name came from the title of a popular song by the Beatles and referred to a child’s slide on a playground. During their murder spree, members of the Manson Family also used their victims’ blood to write words and images, including Helter Skelter, on the walls.

Scarface’s lyrics had also taken on a more sinister dimension.

I sit alone in my four-cornered room staring at candles / Dreaming of the people I’ve dismantled / I close my eyes and in the circle appears / The images of sons of bitches that I murdered

“It was so fuckin’ out there,” DJ Quik said. “Scarface’s words, he sounded like a real funeral-home curator.”

In defending his lyrics, Bushwick Bill said that the Geto Boys’ material was based on actual events and other forms of entertainment. “This is the reality I’ve seen on the news and around me growing up: [The] Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Freddy Krueger,” Bushwick Bill said. “When I turn on the TV, there’s always someone getting raped, someone getting killed.”

This new form of reality rap had a major champion in Rubin, and with the type of trailblazing rap he coveted releasing, Rubin was planning on making a grand reintroduction to the rap world with The Geto Boys. But after hearing the album and facing pushback when the Terre Haute, Indiana–based Digital Audio Disc Corporation, which was contracted to make the CD version of The Geto Boys, refused to manufacture the album because of its content, Geffen Records executives declined to release The Geto Boys and terminated their manufacturing and distribution deal with Rubin’s Def American Recordings.

Geffen Records released a statement about its decision that was printed in the New York Times. “While it is not imperative that lyrical expressions of even our own Geffen artists reflect the personal values of Geffen Records, the extent to which The Geto Boys album glamorizes and possibly endorses violence, racism and misogyny compels us to encourage Def American to select a distributor with a greater affinity for this musical expression.”

Scarface found the move and the label’s position perplexing given the success Geffen was having with X-rated comic Andrew Dice Clay (a Def American artist, no less) and rock group Guns N’ Roses. The former cursed ad nauseam, while the latter was fronted by politically incorrect singer Axl Rose who lamented about “immigrants and faggots” on his group’s song “One In A Million.”

“Axl Rose was running around singing about all of the heroin and easy pussy he was getting, chasing death in the alleys of Los Angeles, and somehow that was okay,” Scarface said, “but those same stories told from our perspective were somehow a problem.”

Rubin, though, understood why Geffen executives declined to release the project. “I don’t think [some people at Geffen] like the record very much, and I can understand why,” he said. “I don’t think it’s unreasonable for anyone not to like it.”

Nonetheless, Rubin was able to find an outlet for The Geto Boys. Eventually released in 1990 by Rap-A-Lot Records in conjunction with Rick Rubin’s Def American Recordings and WEA Manufacturing (whose parent company, Warner Bros., also owned Geffen at the time, ironically), the album came with a sticker on the cover with the following warning: “Def American Recordings is opposed to censorship. Our manufacturer and distributor, however, do not condone or endorse the content of this recording, which they find violent, sexist, racist, and indecent.”

“It was so fuckin’ out there. Scarface’s words, he sounded like a real funeral-home curator.”

DJ QUIK

Scarface said Geffen’s trepidation was about more than the content of the work. “If you ask me, Geffen just didn’t want to see a bunch of niggas make some real money. When you think about all of the shit that we went through just trying to find a place to put our music, it’s hard not to see that shit as what I really think it was: active discrimination. We were entertainers just like the rest of them.”

But when two Dodge City, Kansas, teens were charged with killing a man in 1990, their defense placed blame on the Geto Boys. The teens’ lawyer claimed that the kids were temporarily hypnotized by the Geto Boys’ songs. Just as the Beatles had come under scrutiny because of the Manson Family’s appropriation of their “Helter Skelter” song and rock group Judas Priest had been sued in 1985 after two men entered a suicide pact and shot themselves after getting intoxicated and listening to the band’s Stained Class album, a rap group now found themselves on trial for what their music purportedly encouraged their listeners to do. The jury in the Geto Boys’ case didn’t accept the defense, but the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) blasted the rappers for music it deemed inappropriate.

Perhaps in part due to the media firestorm surrounding The Geto Boys, it failed to go gold, selling fewer than five hundred thousand copies. The Geto Boys’ next album, though, would be the group’s most successful. It also arrived the year that gangster rap exploded in popularity thanks to a series of high-profile albums and movies.