DJ Quik became one of rap’s most popular acts in 1991. The Compton rapper-producer is shown here performing at 92.3 The Beat’s Summer Jam at Irvine Meadows Amphitheater in Irvine, California, on August 8, 1999.

IN AN ATTEMPT TO KEEP THEIR NAME CIRCULATING AFTER ICE CUBE’S SUCCESSFUL SOLO DEBUT, N.W.A RELEASED THEIR 100 MILES AND RUNNIN’ EP ON AUGUST 14, 1990.

But where Ice Cube did not address the departure on his first post-N.W.A project, Dr. Dre took two thinly veiled shots at Ice Cube and his exit from the group on 100 Miles And Runnin’. On the EP’s title track, Dre rapped:

Started with five and, yo, one couldn’t take it / So now there’s four cause the fifth couldn’t make it

Then, on “Real Niggaz,” Dr. Dre compares Ice Cube to the most infamous traitor in American history.

We started out with too much cargo / So I’m glad we got rid of Benedict Arnold

Although these are minor slights when weighed against rap’s typically overly macho posturing, N.W.A’s disses on 100 Miles And Runnin’ nonetheless fanned the flames for the next round of material. Ice Cube returned with his Kill at Will EP on December 18, 1990, but he remained silent about N.W.A. Instead, he focused on the rash of deaths in black urban America (“Dead Homiez”) and pushing the genre into new and interesting sonic directions by taking the music of contemporary rappers D-Nice, EPMD, Public Enemy, Digital Underground, LL Cool J, and X Clan and rapping over their signature instrumentals in what could be seen as a precursor to both the mixtape and “mash-up” waves of music that followed more than a decade later (“Jackin’ for Beats”).

TIMELINE OF RAP

1991

Key Rap Releases

1. N.W.A’s efiL4zaggiN album

2. Geto Boys’ “Mind Playing Tricks on Me” single

3. Ice Cube’s Death Certificate album

US President

George H.W. Bush

Something Else

LAPD officers beat unarmed black motorist Rodney King.

In 1991, as the United States’ international military actions were winding down and domestic strife was increasing as America’s police force aggressively militarized itself, rap was gaining steam. The Gulf War ended when Iraqi troops retreated and the United States reclaimed control of Kuwait. In the Southern Hemisphere, infamous Columbian drug lord Pablo Escobar gave himself up to police in his homeland. Meanwhile in America, racial tensions between blacks, whites, and the police reached a boiling point when footage of Los Angeles police relentlessly beating black motorist Rodney King was captured by an onlooker and released to the media. This video served as a major piece of evidence that backed the numerous claims of police brutality that hardcore rap acts such as Ice-T, Boogie Down Productions, Public Enemy, N.W.A, and others had been voicing for years.

It was at this moment that gangster rap moved from garnering attention from select segments of the population and the media, as it had done throughout the eighties, to dominating commercial media for the first time.

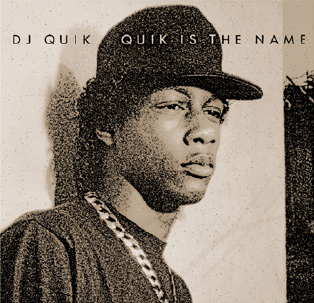

Even though record companies tended to shy away from releasing material in January and February, because the business typically shuts down during the holidays and doesn’t ramp up until the end of January, Profile Records (Run-DMC, Dana Dane, and Rob Base and DJ E-Z Rock) bucked that trend by releasing DJ Quik’s Quik Is the Name in January 1991. The Compton rapper-producer had been infatuated with music since his adolescence and was drawn to the work of funk and soul artists. He started playing instruments before he hit his teenage years, and he had time to focus on his DJing, rapping, and production prowess after being taken in by mentor, fellow rapper, and Penthouse Players Clique member Tweed Cadillac.

Quik Is the Name, the debut collection from DJ Quik, introduced a new sound and style of gangster rap: a largely relaxed and feel-good one in which the protagonist focused as much on women (“Sweet Black Pussy,” “I Got That Feelin’”), getting intoxicated (“Tha Bombudd,” “8 Ball”), and having fun (“Tonite”) as he did on telling tales about the perils of life growing up in the gang-infested Los Angeles metropolitan area (“Born and Raised in Compton,” “Loked Out Hood”).

“I just wanted to write these stories that mirrored what I had just seen, but take the sting out of it with a cool voice,” DJ Quik said. “It was our neighborhood, what’s going on right now just put to a beat.”

On “Loked Out Hood,” DJ Quik also took a dramatic step by naming specific streets in Compton (Aranbe, Spruce, Maple) that would have signaled to listeners familiar with Los Angeles gang culture that he was a member of the Bloods. Prior to that, DJ Quik’s Los Angeles–area forebears (Ice-T, King Tee, N.W.A, Eazy-E) identified and rapped about sections of Los Angeles, but they didn’t identify themselves with streets or neighborhoods synonymous with particular gangs. They also made a point to wear neutral colors (eschewing blue and red specifically) in their videos and on their album covers. This tactic kept gang affiliation from being a promotional or marketing tool. It also gave Los Angeles rappers the biggest consumer base from which to draw, as Bloods and Crips would be less likely to support work from a member of a rival gang.

By March 3, 1991, though, the main group of people the urban black community was rallying against was the police, who were caught on tape beating Rodney King. Black American men had been routinely and unjustly targeted and abused by police for well more than a century, a reality all too often met by indifference, at best, by the legal system and law-enforcement agencies. Now there was a video of an unarmed black man getting savagely attacked by police being aired on a seemingly nonstop loop on news outlets. Five days later, New Jack City arrived in theaters.

GOOD OL’ BOYZ-N-THE-HOOD

GOOD OL’ BOYZ-N-THE-HOOD

Then-Republican Senate Leader Bob Dole sent the following invitation to Eric Wright in February 1991: “Elizabeth and I are looking forward to seeing you in Washington on March 18,” the senator wrote, inviting Wright to join the Republican senatorial inner circle and to attend “Salute to the Commander in Chief,” a Republican luncheon President George H.W. Bush was set to attend.

Dole and his team likely had no idea that Eric Wright was Eazy-E.

A philanthropist who had donated to the City of Hope hospital and Athletes and Entertainers for Kids under his given name, Eazy-E imagined he was invited to the swanky dinner because of his charitable contributions. Intrigued by the opportunity, Eazy-E paid $1,000 for annual dues to the organization and $230 to attend the two-day conference. The N.W.A mastermind—whose group released “Fuck Tha Police”—remained true to form when he showed up for the posh event wearing a Los Angeles Kings hat, a white T-shirt, and a gold and diamond bracelet emblazoned with his rap moniker. The Game was so taken with Eazy-E’s infamous White House attire that he later referenced it on his 2005 single “Dreams.”

Eazy-E said he would have liked to network at the event, and that he endorsed President Bush. “I do support the president’s policy in the Persian Gulf,” said the rapper, who was not a Republican and was not registered to vote. “I’m not against anything, really, that he’s doing.”

Wendy Burnley, the director of communications for the National Republican Senatorial Committee, issued a statement regarding Eazy-E’s attendance at the event. “This is clear and convincing evidence of the success of our new Rap-Outreach program. Democrats, eat your hearts out.”

The film follows vicious crime lord Nino Brown (Wesley Snipes), who rises to power during the crack epidemic by implementing an expertly efficient, supremely organized, and remarkably ruthless team to manage, distribute, and sell his drugs. The off-kilter undercover police officer charged with ending Brown’s run is Scotty Appleton (Ice-T).

New Jack City provided a snapshot of what was happening in black urban communities across the United States and showed how difficult it was for well-intentioned police officers to take on better-funded, better-armed, and particularly savvy drug dealers and their crime syndicates. Yet, in the real-life wake of N.W.A’s “Fuck tha Police,” the federal government waged a censorship war against N.W.A, the Geto Boys, Ice-T, and others. Hence, by portraying a police officer in a major motion picture, Ice-T was taking a tremendous career risk. He was, in effect, humanizing the police officer, showing that there was more to the story than just black versus white, us against them, and the system against poor black people in America.

Ice-T’s New Jack City gamble paid off handsomely.

Released by film industry stalwart Warner Bros. Pictures, New Jack City appealed to the rap audience thanks to Ice-T’s leading role, well-placed cameos from rap industry heavyweights (Fab 5 Freddy, Public Enemy’s Flavor Flav), a predominantly black cast, and the quality story, which revered movie critic Roger Ebert trumpeted in his 3.5-out-of-4-star review: “By the end of the film, we have a painful but true portrait of the impact of drugs on this segment of the black community: We see how they’re sold, how they’re used, how they destroy, what they do to people.”

New Jack City peaked at No. 2 at the box office, grossing $47 million against a reported $8.5 million budget. The film also benefitted from a sterling soundtrack anchored by Ice-T’s “New Jack Hustler (Nino’s Theme)” and Color Me Badd’s sensual R&B smash hit “I Wanna Sex You Up.”

In signature Ice-T fashion, “New Jack Hustler (Nino’s Theme)” showed the criminal underworld from the perspective of those living a life similar to Nino Brown’s character in New Jack City, but with a dose of compassion and insight into the conflicted minds of some of the men caught up in the drug-dealing lifestyle.

I had nothing, and I wanted it / You had everything, and you flaunted it / Turned the needy into the greedy / With cocaine, my success came speedy / Got me twisted, jammed into a paradox / Every dollar I get, another brother drops / Maybe that’s the plan and I don’t understand / Goddamn, you got me sinkin’ in quicksand / But since I don’t know, and I ain’t never learned / I gotta get paid, I got money to earn

Released on March 5, 1991, the New Jack City soundtrack sold more than one million copies by May 1991, earning platinum status.

BOX-OFFICE PERFORMANCE OF RAP-RELATED FILMS RELEASED THROUGH THE END OF 1991

FILM: Wild Style (1983)

SHOOT LOCATION: New York

BUDGET: N/A

BOX OFFICE: N/A

ROTTEN TOMATOES RATING: 89%

FILM: Breakinx (1984)

SHOOT LOCATIONS:

Los Angeles and Venice

Beach, California

BUDGET: $1.2 million

BOX OFFICE: $38.7 million

ROTTEN TOMATOES RATING: 43%

FILM: Krush Groove (1985)

SHOOT LOCATION: Bronx, New York

BUDGET: $3 million (estimated)

BOX OFFICE: $11 million

ROTTEN TOMATOES RATING: 43%

FILM: House Party (1990)

SHOOT LOCATION: Los Angeles

BUDGET: $2.5 million (estimated)

BOX OFFICE: $26.3 million

ROTTEN TOMATOES RATING: 96%

FILM: New Jack City (1991)

SHOOT LOCATION: New York

BUDGET: $8.5 million

BOX OFFICE: $47.6 million

ROTTEN TOMATOES RATING: 77%

FILM: Boyz N the Hood (1991)

SHOOT LOCATIONS: Los Angeles and

Inglewood, California

BUDGET: $6.5 million (estimated)

BOX OFFICE: $57.5 million

ROTTEN TOMATOES RATING: 96%

May 1991 also saw the release of Ice-T’s fourth album, O.G. Original Gangster. The LP included “New Jack Hustler (Nino’s Theme),” and with the surging popularity of gangster rap, Ice-T released the album’s title track as a single with an accompanying video. He then went on to take the groundbreaking step of making a video for every track on the collection, a first in any genre.

With three gold albums, numerous national and international tours, and a burgeoning empire with his Rhyme Syndicate label and management company (which had handled King Tee, WC, and Everlast, among others) under his belt, Ice-T wanted to cement his status as a pioneer with “O.G. Original Gangster,” an autobiographical chest-thumping exercise that traces his evolution as a rapper, as well as the entire gangster rap subgenre.

When I wrote about parties, it didn’t fit / “6 ’N the Mornin’,” that was the real shit . . . When I wrote about parties, someone always died / When I tried to write happy, yo, I knew I lied / ’Cause I live a life of crime

America’s fascination with a life of crime had been well documented throughout the years, as evidenced by the country’s affinity for organized crime beginning in the thirties, and by the commercial and critical success of such high-profile seventies and eighties films as The French Connection, The Godfather, Scarface, and Once Upon a Time in America, among others. But the leading personalities and characters in those organizations and in those films weren’t black. New Jack City’s success, however, showed that there was a desire to see black characters on both sides of the law in major motion pictures.

GANGSTER RAP SALES

VS. OTHER RAP SALES

GANGSTER RAP ALBUMS

Quik Is the Name by DJ Quik

Release date: January 15, 1991

Certified gold: May 30, 1991

Certified platinum: July 26, 1995

New Jack City soundtrack

Release date: March 5, 1991

Certified gold: May 24, 1991

Certified platinum: May 24, 1991

O.G. Original Gangster by Ice-T

Release date: May 14, 1991

Certified gold: July 24, 1991

Efil4Zaggin by N.W.A

Release date: May 29, 1991

Certified gold: August 8, 1991

Certified platinum: August 8, 1991

We Can’t Be Stopped by the Geto Boys

Release date: June 29, 1991

Certified gold: September 11, 1991

Certified platinum: February 26, 1992

Boyz N the Hood soundtrack

Release date: July 9, 1991

Certified gold: September 12, 1991

Cypress Hill by Cypress Hill

Release date: August 9, 1991

Certified gold: March 26, 1992

Certified platinum: January 5, 1993

Certified double platinum: May 30, 2000

Mr. Scarface Is Back by Scarface

Release date: October 1, 1991

Certified gold: April 23, 1993

Death Certificate by Ice Cube

Release date: October 21, 1991

Certified gold: December 20, 1991

Certified platinum: December 20, 1991

2Pacalypse Now by 2Pac

Release date: October 28, 1991

Certified gold: April 19, 1995

Juice soundtrack

Release date: December 31, 1991

Certified gold: March 4, 1992

NON–GANGSTER RAP ALBUMS

De La Soul Is Dead by De La Soul

Release date: May 14, 1991

Certified gold: July 18, 1991

Homebase by D.J. Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince

Release date: July 9, 1991

Certified gold: September 19, 1991

Certified platinum: September 19, 1991

A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing by Black Sheep

Release date: August 6, 1991

Certified gold: April 3, 1992

Naughty by Nature by Naughty by Nature

Release date: September 3, 1991

Certified gold: November 13, 1991

Certified platinum: February 6, 1992

Sports Weekend (As Nasty as They Wanna Be Part II) by 2 Live Crew

Release date: September 23, 1991

Certified gold: April 16, 1992

The Low End Theory by A Tribe Called Quest

Release date: September 24, 1991

Certified gold: February 19, 1992

Certified platinum: February 1, 1995

Apocalypse 91…The Enemy Strikes Black by Public Enemy

Release date: September 27, 1991

Certified gold: November 26, 1991

Certified platinum: November 26, 1991

Bitch Betta Have My Money by AMG

Release date: September 30, 1991

Certified gold: September 28, 1994

Too Legit to Quit by Hammer

Release date: October 28, 1991

Certified gold: January 8, 1992

Certified triple platinum: January 8, 1992

Similarly, the success of N.W.A’s Efil4Zaggin album (“Niggaz 4 Life” spelled backward) demonstrated that the audience for gangster rap was even larger than almost anyone realized. Released on May 28, 1991, the second studio album from N.W.A was its first without Ice Cube (following their extended play project 100 Miles And Runnin’).

N.W.A, however, was not so courteous on Efil4Zaggin. On lead single “Alwayz Into Somethin’,” Dr. Dre rapped about going to pick up MC Ren. Dre then hears gunshots, sees someone hopping a fence, and then MC Ren jumps into his Mercedes-Benz. Dre recounts Ren’s statement to him.

“Dre, I was speakin’ to yo’ bitch O’Shea”

O’Shea Jackson is Ice Cube’s given name, so in addition to calling Ice Cube Dre’s bitch, it is implied that MC Ren had just finished shooting Ice Cube. That wasn’t the worst of Efil4Zaggin’s Ice Cube bashing, though. In the interlude of the next track of the collection, “Message to B.A.,” a series of phone messages are played in which Ice Cube is dissed for not being from Compton (Ice Cube is from South Central Los Angeles but rapped on “Straight Outta Compton”) and for jumping on the East Coast rap bandwagon (Ice Cube worked with New York–based producers the Bomb Squad on AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted), among other slights. Then MC Ren says: “Yeah, nigga. When we see yo’ ass, we gon’ cut your hair off and fuck you wit’ a broomstick.”

With Efil4Zaggin, N.W.A was making good on Dr. Dre’s 1989 edict to be more violent, more confrontational, and more outrageous than they had been on Straight Outta Compton. Just on song titles alone, N.W.A had ratcheted up its potential offensiveness. “Real Niggaz Don’t Die,” “Niggaz 4 Life,” “Real Niggaz,” “To Kill a Hooker,” “One Less Bitch,” “Findum, Fuckum & Flee,” and “I’d Rather Fuck You” took sex, violence, and the use of the word nigga, and its various incarnations, to new rap levels thanks to Dr. Dre and DJ Yella’s searing production and the profanity-saturated lyrics of MC Ren, Eazy-E, and Dr. Dre. There was also “She Swallowed It,” the group’s sequel to 100 Miles And Runnin’ track “Just Don’t Bite It.” Both selections were tributes to receiving oral sex that contained instructions for women on how to properly perform fellatio on a man.

Efil4Zaggin may have been lacking the political bite of Ice Cube’s AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, but N.W.A’s fan base flocked in droves to the record stores to purchase the group’s second (and what would be final) studio album. Efil4Zaggin entered the Billboard charts as the No. 2 album in the country. The next week, the project made history.

For the first forty-five years of the Billboard charts, album sales were reported on an honor system in which record stores and DJs would name the most popular artists at that time. Naturally, personal whims, biases, and payola likely influenced who a record store representative reported as being popular. But thanks to the advent of SoundScan, which tracked sales by a project’s UPC, or bar code, for the first time, tallies from retail outlets became the driving force in creating Billboard charts. Gangster rap wasted no time in showing its power.

On the June 22, 1991, chart, the new Billboard sales system using SoundScan was employed. The No. 1 album in the country during that sales week: N.W.A’s Efil4Zaggin, becoming the first No. 1 album in the SoundScan era and the first gangster rap album to earn the No. 1 slot on the Billboard 200 chart. By simply measuring the actual sales of albums, N.W.A rose on the charts and outsold every other album in the country, including rock group R.E.M.’s smash Out of Time album, which held the No. 1 spot under the old chart system. The popularity of gangster rap was now quantified and verified.

Released on Eazy-E’s Ruthless Records/Priority Records, N.W.A’s Efil4Zaggin showed that independent gangster rap was the bestselling and fastest-selling music in the country.

YO! MTV RAPS = PLATINUM

DJ Quik’s first album, 1991’s Quik Is the Name, sold more than one million copies. He credits the exposure his videos got on Yo! MTV Raps for making his collection a brisk seller. “I don’t believe for a moment that my debut record would have gone platinum as soon as it did without MTV,” DJ Quik said. “At that point, MTV was like Twitter is now to music and to culture. At that time, they were the be all[, end all] in media. That was it.”

Soon thereafter, Priority Records enjoyed another breakthrough success. After a messy divorce from Rick Rubin’s Def American Recordings and parent company Geffen Records, Rap-A-Lot Records signed a deal to partner with Priority Records for its releases. All was not well with the Geto Boys, however. During a drug- and alcohol-fueled argument with his girlfriend on June 19, 1991, Bushwick Bill begged her to shoot and kill him. She did her best, shooting the rapper in his right eye.

Ever the shrewd businessman, label owner James “J.” Prince turned tragedy into triumph. J. Prince had a picture taken of Bushwick Bill on a gurney with fellow Geto Boys members Willie D and Scarface flanking him in a hospital hallway. Bushwick Bill had just emerged from surgery and the graphic image showed his exposed, blood-stained, and severely damaged eye. J. Prince used the image as the cover art of the Geto Boys’ next album—their first with Priority Records—1991’s We Can’t Be Stopped.

Released on July 2, 1991, We Can’t Be Stopped was quickly certified platinum with sales in excess of one million copies. The album also spawned the hit single “Mind Playing Tricks on Me,” which became a mainstay on MTV. Scarface’s opening lines, which incorporated some of his lyrics from the group’s gruesome “Mind of a Lunatic,” set the stage for the group’s song about paranoia, doubt, and depression. “Mind Playing Tricks on Me” ended up being the Geto Boys’ most popular song. Its success, and that of We Can’t Be Stopped as a whole, again showed that the Geto Boys and gangster rappers could be commercial juggernauts on their own terms.

As gangster rap was finally getting the chart recognition it deserved, it was about to hit another major milestone in film with Boyz N the Hood. Released on July 12, 1991, the movie, which stars Ice Cube, Cuba Gooding Jr., and Laurence Fishburne, follows the lives of three young men (an athlete, a scholar, and a gang member) growing up in South Central Los Angeles. The gritty film showed how gangs, guns, and drugs were ravaging Los Angeles, ending the lives of innocents and criminals alike.

Like New Jack City before it, Boyz N the Hood was a commercial and critical success. It hit No. 3 at the box office, grossing $57 million against a $6.5 million budget, and was nominated for two Academy Awards. John Singleton became the youngest director and the first black person to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director. Singleton was also nominated for Best Writing (Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen) for his script.

The Boyz N the Hood soundtrack was buoyed by the Ice Cube single “How to Survive in South Central” and the breakthrough single “Growin’ Up in the Hood” by Compton’s Most Wanted. On the latter, group member MC Eiht rapped in the first person about his exploits growing up with an emotionally distant mother, getting incarcerated, getting released, witnessing the shootings of his brother and mother, and killing the guys who shot his family. Fellow Compton’s Most Wanted rapper Tha Chill focused his verses on how the police were trying to arrest him and the community wanted him to set up his drug-dealing business elsewhere. Unlike MC Eiht, though, Tha Chill ends up dead at the end of “Growin’ Up in the Hood.” The song’s visual storytelling style and poignant lyrics showing the pain and struggle of living in the black Los Angeles ghetto resonated with fans. The Boyz N the Hood soundtrack went on to sell more than five hundred thousand copies, qualifying it for a gold certification.

“Growin’ Up in the Hood” was also featured on Compton’s Most Wanted’s Straight Checkn ’Em, their second studio album. The album arrived in stores on July 16, four days after Boyz N the Hood became a box-office sensation.

With the success of King Tee, Eazy-E, N.W.A, DJ Quik, and Compton’s Most Wanted, Compton had become one of the most exciting cities in rap. The emergence of DJ Quik and Compton’s Most Wanted also showed that the second wave of Compton gangster rap had already arrived.

Gangster rap’s next breakthrough and subgenre came from Cypress Hill. The Los Angeles–based trio of rappers, including B-Real and Sen Dog and producer DJ Muggs, was significant for several reasons. For one, none of the members were black Americans. B-Real had a Mexican father and a Cuban mother, while Sen Dog was of Cuban heritage, and DJ Muggs was a New Yorker of Italian and Cuban descent. The group also added a distinctive wrinkle to this brand of hardcore rap, making their affinity for marijuana a hallmark of their music. Cypress Hill’s self-titled album was released on August 13, 1991, and featured the pro-weed songs “Light Another,” “Stoned Is the Way of the Walk,” and “Something for the Blunted,” while also championing the group’s heritage (“Latin Lingo,” “Tres Equis”), their disdain for crooked police (“Pigs”), and their gangster, gun-toting ways (“How I Could Just Kill a Man” [the video featured a cameo from Ice Cube], “Hand on the Pump,” “Hole in the Head”).

The Geto Boys’ Scarface also made gunplay a focal point of his debut solo album, Mr. Scarface Is Back. Released on October 1, 1991, the project featured a deep dive into the Houston rapper’s murderous mentality. “Mr. Scarface,” “Born Killer,” and “Murder by Reason of Insanity” detailed Scarface’s gruff and violent personality, while “Good Girl Gone Bad” and “A Minute to Pray and a Second to Die” showed his introspective side, framing passionate stories of deceit and revenge against the backdrop of drugs and homicide.

As Scarface was separating himself as the standout rapper of the Geto Boys, Ice Cube made one of the most powerful statements in rap to that point with his conceptually rich Death Certificate album, which examined the mental and physical status of blacks in America. The searing collection concludes with “No Vaseline,” widely regarded as one of the most potent diss songs in rap history. Ice Cube employed a tactic on “No Vaseline” similar to the one he used on the AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted cut “The Nigga Ya Love to Hate,” which featured a chorus of people chanting “Fuck you, Ice Cube!” In that instance, he was empowering himself by dissing himself. On “No Vaseline,” however, he was about to turn that idea on its head.

Ice Cube starts the song off by playing portions of his work with N.W.A and Eazy-E (including Eazy-E rapping, “Ice Cube writes the rhymes that I say” on “The Boyz-N-The Hood”), as well as the Efil4Zaggin cut “Message to B.A.” Ice Cube flipped the script, though, by mimicking “Message to B.A.” and including sound bites of people dissing Dr. Dre and DJ Yella in particular and N.W.A in general, saying they “ain’t shit without Ice Cube.”

It’s the first verse on “No Vaseline,” though, where Ice Cube took rap disses to a new level. He clowns the crew for working with R&B singer Michel’le, who was also Dr. Dre’s girlfriend at the time, and for moving out of Compton to a white neighborhood. Ice Cube dismisses DJ Yella’s production skills and says Dr. Dre should leave rapping alone and stick to producing. He then accuses Eazy-E of raping Dr. Dre—likely meant to represent the idea that Eazy-E wasn’t paying Dr. Dre what he was worth, as was the case with Eazy-E and Ice Cube before Ice Cube’s departure from the group.

The second verse is equally arresting. Ice Cube says Eazy-E is financially and literally screwing MC Ren. He then alludes to MC Ren’s threat on Efil4Zaggin’s “Message to B.A.,” that N.W.A was “gon’ cut your hair off and fuck you wit’ a broomstick.”

NEW YORK & CALIFORNIA SENSIBILITIES CLASH

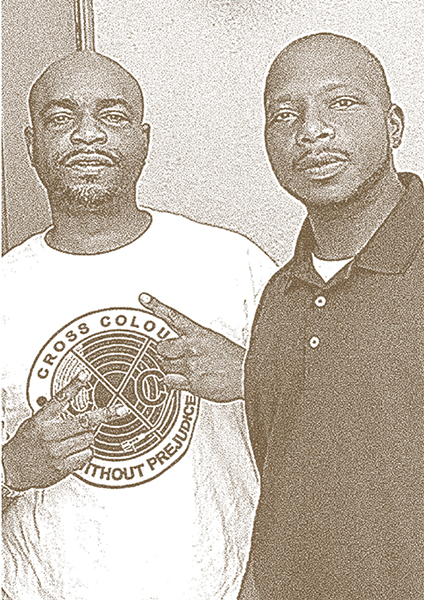

DJ Quik protégés 2nd II None (Gangsta D and KK) enraged rap purists when they said on Yo! MTV Raps that they didn’t freestyle. This is an early example of what would be a huge rift between segments of East Coast and West Coast rappers (both DJ Quik and 2nd II None are from Compton), as the New Yorkers felt that the West Coast rappers weren’t real MCs and didn’t take the craft seriously.

2nd II None members Gangsta D (left) and KK.

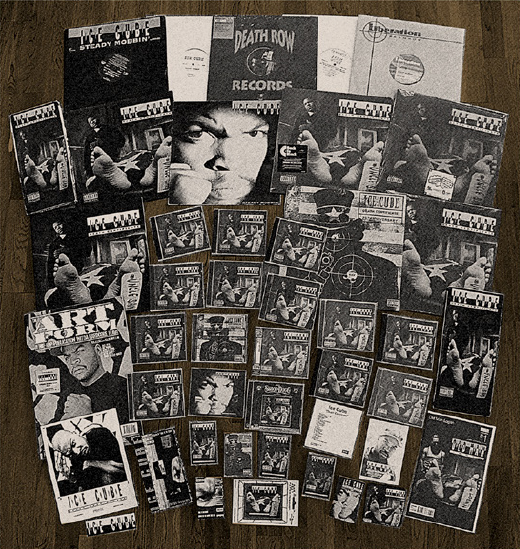

COLLECTING ICE CUBE’S DEATH CERTIFICATES

Amir Rahimi didn’t just want one copy of Ice Cube’s Death Certificate album. Instead, the music collector wanted every version of the album ever released. To date, Rahimi has twenty-eight different versions of the LP, and a total of forty-four items related to the LP, which was originally released in 1991.

Rahimi, who started collecting in 2004, when he was twelve, believes Death Certificate is the best rap album of all time, that it contains the greatest diss song of all time in “No Vaseline,” and that it shows Ice Cube’s brilliance as an artist because, among other things, “Color Blind” is the only song on the entire album that features other artists.

“Death Certificate features an Ice Cube in his prime talking about a wide range of topics, including, but not limited to, racism, gangs, drugs, STDs, self-improvement,” said Rahimi, founder of the Rappin’ and Snackin’ website.

The Southern California resident, who became obsessed with rap when his friend burned him copies of 2Pac’s Me Against the World and Loyal to the Game albums, looks for new versions of Death Certificate in a variety of ways. He asks friends online that have versions he hasn’t seen. He checks #DeathCertificate on Instagram, especially around the anniversary of the album’s release. He also regularly searches Discogs, an online music database and marketplace.

Among his most cherished editions of Death Certificate are a Japanese edition with an obi strip, and a Russian version that features Russian words above the parental advisory label. His favorite, though, is an original pressing of the vinyl version of the album, which is sealed and in mint condition. Rahimi said the album could fetch between $50 and $75.

“For over twenty-five years, it’s stayed perfect,” Rahimi said. “It’s like you picked it off the rack at the store today.”

The broomstick fit your ass so perfect / Cut my hair? Naw, cut them balls / ’Cause I heard you like giving up the draws / Gangbanged by your manager, fella

Ice Cube’s onslaught continued, saying that N.W.A let a “Jew,” ostensibly Jerry Heller, break up his crew in a classic case of divide and conquer.

Eazy-E was Ice Cube’s next “No Vaseline” target. In addition to calling him a “house nigga,” “half-pint bitch” (Eazy-E was reportedly 5’5”), and a “faggot,” he advocated hanging Eazy-E from a tree and lighting him and his Jheri curl on fire.

Ice Cube’s rhymes about Jerry Heller were equally sinister.

Get rid of that Devil real simple / Put a bullet in his temple / ’Cause you can’t be the Nigga 4 Life crew / With a white Jew telling you what to do

In his memoir fifteen years later, Heller wrote that he was fed up with Ice Cube’s disses, which included interviews as well as songs. “I’m tired of your slurs,” Heller wrote. “It makes me sick that you exploit the anti-Semitism rampant in the world today just to justify yourself.”

In 2015, Ice Cube said he regretted using anti-Jewish language on “No Vaseline.” “I didn’t know what ‘anti-Semitic’ meant, until motherfuckers explained why it was just not okay to lump Jerry with anybody cool,” Ice Cube said. “But I wasn’t like, ‘I wanna hurt the whole Jewish race.’ I just don’t like that motherfucker.”

N.W.A, though, did not respond to “No Vaseline.” As the last cut on Death Certificate, it was an explosive and incongruous end to an album simmering with social commentary and insightful looks at how the American system was failing its black population. “My Summer Vacation” provides a look at how gangs, drugs, and the respective cultures surrounding them spread from Los Angeles to the Midwest. On “A Bird in the Hand,” Ice Cube tells the story of a high school graduate and father who, despite earning great grades, doesn’t have money for college and doesn’t land a job he wanted at AT&T. He ends up working at McDonald’s and decides that, given the options he sees for himself, his best course of action is to sell drugs to support his family.

With “Alive on Arrival,” Ice Cube raps about going to the hospital with a gunshot wound, being forced to fill out paperwork, getting handcuffed and interrogated by police about the shooting, and waiting more than an hour to be seen by an overworked physician before eventually dying handcuffed to the bed. The death of the “Alive on Arrival” protagonist leads into “Death,” the end of the Death Side of Death Certificate. The second side, or the Life Side, opens with “The Birth,” a signal for the rebirth and the resurrection of the black community.

“I Wanna Kill Sam” features Ice Cube imagining killing Uncle Sam because of the racist and oppressive American system he has created and sustains, while “Black Korea” lamented black customers being followed and harassed in stores. At the end of the song, Ice Cube said that these types of store owners needed to respect their black patrons. Otherwise, they’d face either a boycott or their businesses burning to the ground. The song was likely inspired, at least in part, by the shooting of Latasha Harlins, a fifteen-year-old black girl who was shot and killed in Los Angeles by Soon Ja Du, a female convenience store owner from South Korea who thought Harlins was attempting to steal a bottle of orange juice from the store. After a physical altercation with Du, Harlins put the juice on the counter and attempted to leave the store. Du shot Harlins in the back of the head, killing her instantly. Du was convicted of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced to five years of probation, four hundred hours of community service, and a five-hundred-dollar fine.

“I’m tired of your slurs. It makes me sick that you exploit the anti-Semitism rampant in the world today just to justify yourself.”

JERRY HELLER

TO ICE CUBE

Ice Cube and guest rappers Threat, Kam, WC, Coolio, King Tee, and the Lench Mob’s J-Dee also take sobering looks at living the life of a gangbanger on “Color Blind,” while Ice Cube points the finger at black America for contributing to its problems on “Us.” He cites jealousy, envy, and backstabbing as systemic and crippling issues in the black community. Rather than glorify drug-dealing, Ice Cube condemns the trade, likening drug dealers to the police (they both kill black people in the neighborhood) and blasting them for buying Cadillacs without investing in improving the community.

Exploitin’ us like the Caucasians did / For four hundred years, I got four hundred tears / For four hundred peers / Died last year from gang-related crimes / That’s why I got gang-related rhymes

Released on October 29, 1992, Ice Cube’s Death Certificate album debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard charts, cementing his status as one of rap’s most significant and popular artists.

Less than a month later, on November 12, 1992, former Digital Underground dancer and roadie 2Pac released his debut album, 2Pacalypse Now. 2Pac’s album was filled with songs and lyrics about killing police officers, being there for his friends at all costs, feeling trapped in the corrupt American justice system, and the far-reaching fallout of preteen pregnancies. Although 2Pac would soon become one of rap’s most iconic figures, 2Pacalypse Now did not gain a large audience, taking three and a half years to go gold.

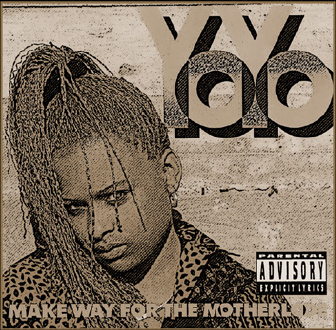

Make Way for the Motherlode by Yo-Yo (March 19).

The debut album from Ice Cube’s female protégé contained a number of no-nonsense female empowerment lyrics.

Addictive Hip Hop Muzick by Who Am I? (July 2).

The Eazy-E-backed debut album from rapper-singer Kokane introduced another talented member of the Ruthless Records roster. He went by Who Am I? because major label Epic Records didn’t want to release an album by an artist named Kokane.

Vocally Pimpin’ by Above the Law (July 16).

This EP and its 1992 follow-up, Black Mafia Life, laid the sonic foundation for Dr. Dre’s The Chronic.

MC Breed & DFC by MC Breed and DFC (August 13).

The Flint, Michigan, crew scored a funk-driven hit with “Ain’t No Future in Yo’ Frontin’.”

Ain’t a Damn Thang Changed by WC and the Maad Circle (September 17).

Formerly one-half of Low Profile, WC returned with his new crew, the Maad Circle. Members included Coolio and WC’s late brother and DJ, Crazy Toones, among others.

A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing by Black Sheep (October 22).

The debut album from the New York duo of Dres and Mista Lawnge contained “U Mean I’m Not,” a gangster rap parody in which a school-aged Dres imagines himself shooting his sister because she used his toothbrush, his mother because she messed up his egg breakfast, and his father after he protested the events. As he exits his house, Dres cuts the mailman’s throat and then waits for the school bus.

Bitch Betta Have My Money by AMG (December 3).

The DJ Quik affiliate delivered a series of clever, sexually slanted rhymes over funk-drenched beats.

Also released on November 12 was the first anti–West Coast gangster rap album, Tim Dog’s Penicillin on Wax. Rather than celebrating the culture, the Bronx, New York–based Ultramagnetic MCs affiliate spent much of the album disparaging gangster rap, particularly the West coast side of it. With “Fuck Compton,” Tim Dog dissed the city itself in addition to taking digs at Eazy-E, Ice Cube, and N.W.A. He also boasted of having sex with Michel’le, Dr. Dre’s then-fiancée. But Tim Dog took things even further by dissing the West Coast’s entire gang culture.

Having that gang war / We want to know what you’re fighting for / Fighting over colors? / All that gang shit’s for dumb motherfuckers / But you go on thinking you’re hard / Come to New York and we’ll see who gets robbed

The rest of Penicillin on Wax included disses of DJ Quik (“DJ Quick Beat Down”), a talk about dissing Dr. Dre with a Michel’le impersonator (“Michel’le Conversation”), and a song that hinted at the reason Tim Dog may have made “Fuck Compton” and taken his aggressive anti-Compton stance (“I Ain’t Havin’ It”).

Although Ice Cube had collaborated with Public Enemy on Fear of a Black Planet and worked with the Bomb Squad on his AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, there was a growing, unspoken tension between artists from the East Coast and artists from the West Coast. Rap started in New York, and for the first time in the genre’s history, rappers from the West Coast were the ones selling more records, garnering more media attention, and shaping the culture more than their East Coast contemporaries. It’s a phenomenon that got its start with Eazy-E and N.W.A in 1989 and avalanched in 1991 thanks to the commercial success of DJ Quik, N.W.A, Ice-T, Compton’s Most Wanted, Cypress Hill, and Ice Cube.

Furthermore, the success of New Jack City and Boyz N the Hood, as well as the 1990 comedy House Party starring lighthearted rap duo Kid ’n Play, ushered in a new era of black cinema, the likes of which had not seen been since blaxploitation.

The year in rap—which concluded with the December 31 release of the soundtrack for Juice, the film starring 2Pac in his breakthrough role—had been defined by the expansion and intensification of gangster rap. DJ Quik blended good times, menace, and musicianship in his work, while Ice-T’s insightful rhymes and a powerful screen performance showed how the genre’s pioneers could achieve longevity. N.W.A took the music to dark, savage places, while Compton’s Most Wanted provided a street-level reporting perspective. Cypress Hill rapped about Los Angeles’s drugs, gangs, police, and crime from a Latin perspective, while Ice Cube crystallized the experience of blacks living in the ghettos of America. 2Pac also railed against the American system from a position of outrage and vengeance, while Tim Dog showed that a rift was emerging between New York and Los Angeles artists.

While all these events were significant in their own rights, they were recognized primarily within the emerging rap community and not in the larger musical or cultural scene. Gangster rap’s next milestone, however, took the genre to a new place: true mainstream acceptance from the media, radio, and television.