Warren G (left) and Sir Jinx in Hawaii for Los Angeles radio station Power 106’s Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg reunion concert in September 1999.

IN 1994, THE WORLD VACILLATED BETWEEN LONGSTANDING WRONGS FINALLY BEING RIGHTED AND NEW MORAL ATROCITIES.

Nelson Mandela was sworn in as South Africa’s first black president, a groundbreaking step after the fall of apartheid, the country’s governmental system that practiced institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination. The Rwandan genocide began after a plane with the Rwandan and Burundian presidents was shot down. The event led to the Rwandan Hutu ethnic group slaughtering approximately seven thousand members of the country’s Tutsi population in a stadium in the city of Kibuye.

In the shadow of those evils, justice was served in a number of high-profile ways in the United States. Byron De La Beckwith was sentenced to life in prison thirty years after killing civil rights leader Medgar Evers. Rodney King was awarded $3.8 million in compensation from the City of Los Angeles for his beating at the hands of the Los Angeles Police Department. A federal jury also convicted all four men on trial for the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York that killed six people and caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damages. The charges included using a destructive device resulting in death and the destruction of government property.

TIMELINE OF RAP

1994

Key Rap Releases

1. Warren G & Nate Dogg “Regulate” single

2. OutKast’s Southern-playalisticadillacmuzik album

3. Nas’s Illmatic album

US President

Bill Clinton

Something Else

Amazon.com was founded.

By 1994, rap was enjoying more than a decade of sustained exponential growth. The genre had grown from an almost exclusively New York–area marvel into an international phenomenon whose tentacles continued expanding into other forms of media. Gangster rappers, in particular, had also shown their keen ability to evolve and find success beyond simply making music.

Schoolly D, for instance, was working extensively on soundtracks and scores for such movies as King of New York and Bad Lieutenant, with acclaimed indie film director Abel Ferrara. After their respective breakthrough film roles in 1991, both Ice-T (New Jack City) and Ice Cube (Boyz N the Hood) were establishing themselves as bankable actors and had starred together in the heist film Trespass.

“N.W.A was on some damn-near Public Enemy shit with their beats. Above the Law came and slowed it down.”

YUKMOUTH

As rap music entered the New Year, there were two major long-simmering breakthroughs on the horizon—both able to show that gangster rap could connect with people in less menacing ways and with dramatically different sounds. The first was something that Above the Law created, Dr. Dre popularized, Snoop Dogg named, and Warren G branded.

The percolation began in 1990. During the height of Ruthless Records, Eazy-E signed the rap group Above the Law to his record label. Based in Pomona, California (about thirty miles east of Los Angeles), the group consisted of rapper-producer Cold 187um, rapper KMG the Illustrator, DJ Total K-Oss, and DJ Go Mack. Their first album, 1990’s Livin’ Like Hustlers, was produced by Dr. Dre, Laylaw (also the group’s manager), and Above the Law, and featured the rap hits “Murder Rap” and “Untouchable,” as well as the posse cut “The Last Song” with N.W.A.

Lyrically, Livin’ Like Hustlers dealt with the common gangster rap themes of violence, drugs, and sex, but Above the Law also added a political undercurrent to much of their work, and focused on being hustlers, players, and pimps more than straight-up gangsters. They also introduced the idea of a black mafia to the rap world. Furthermore, Cold 187um (also known as Big Hutch) and KMG the Illustrator rapped differently than many other rappers of the era, choosing a more deliberate, steady delivery than that of most of their contemporaries. Additionally, Cold 187um’s higher-pitched, nasal tone played well with KMG’s deeper, huskier voice.

“They slowed that shit completely down to where they’re talking to you,” Yukmouth said. “It felt like a conversation when you’re in the car. You’re bumping [the music and] are like, ‘Is the muthafucker talkin’ to me?’ It felt like that and it hit home like that. You could understand it, and it ain’t too tricky to where you’ve got to listen to it one thousand times to figure out what this nigga said, or go look in a thesaurus or dictionary to figure it out. It was straight to the point.”

It was sonically, though, that Above the Law made their most profound impact.

In the late eighties, EPMD, Eazy-E, and N.W.A had released music using funk samples in their respective works. So did conscious rap group X Clan, which rapped over Parliament’s beats on their 1990 album To the East, Blackwards, most notably on their single “Funkin’ Lesson” and album cut “Earth Bound.” Similarly, Ice Cube protégé (and younger cousin) Del tha Funkee Homosapien rapped over Funkadelic’s beats on his 1991 album, I Wish My Brother George Was Here.

But both X Clan and Del tha Funkee Homosapien rapped in esoteric rhymes, with X Clan’s black nationalistic lyrics and Del tha Funkee Homosapien’s equally dense songs about everyday struggles earning them cult followers among certain demographics of the expanding rap fan base. But neither of the acts (nor EPMD, Eazy-E, or N.W.A before them) made funk the foundation of their musical identity in the way that Above the Law did. They were not purely gangster rappers, either.

ICE-T AND N.W.A brought West Coast gangster rap to the forefront in the mid-1980s, setting the stage for dozens of other hardcore Southern California rap acts to rise to prominence. Although collaborations between artists in the 1980s and early 1990s were not as common as they would be a few years later, Ice-T worked with N.W.A and its members several times throughout the years, from tours to movies and songs. Here are three standout collaborations.

“We’re All in the Same Gang” (1990). As members of The West Coast Rap All-Stars, Ice-T appeared with Eazy-E, Dr. Dre, and MC Ren on the antigang and antiviolence song, which was also produced by Dr. Dre.

Trespass (1992). Ice-T and Ice Cube starred with Bill Paxton and William Sadler in this action thriller about two firemen (Paxton and Sadler) who find a map to stolen gold in an abandoned East St. Louis factory that is used by a local gang helmed by King James (Ice-T). James and his subordinate (Ice Cube) argue about how to eliminate the trespassers.

“Last Wordz” (1993). Ice-T and Ice Cube appeared together on this hard-hitting song from Strictly for My N.I.G.G.A.Z., 2Pac’s second album. The Ices boasted of their thuggish ways in their rhymes, while 2Pac positioned himself as a violent revolutionary in his verse.

When Above the Law emerged in 1990, producer Cold 187um incorporated samples from, at the time, unconventional musical sources for rap, such as Quincy Jones and Isaac Hayes. The following year, Cold 187um developed the sound that would shape that of gangster rap for the next several years. He produced Above the Law’s 1991 EP, Vocally Pimpin’. The nine-song project was anchored by the single “4 the Funk of It,” which borrowed its groove and some of the lyrics of its chorus from Funkadelic’s “One Nation Under a Groove,” a funk music staple.

Cold 187um delved deeper into the funk vaults on Above the Law’s second album, Black Mafia Life, which was released in 1992. He made the sound Above the Law’s signature, kicking off the project with “Never Missin’ a Beat,” which featured a sample of Funkadelic’s “(Not Just) Knee Deep.” Cold 187um’s cousin singer-rapper Kokane delivered vocals that mimicked the work of the Parliament and Funkadelic vocalists.

The second song on Black Mafia Life, “Why Must I Feel Like Dat,” sampled George Clinton’s “Atomic Dog” and Parliament’s “I Can Move You (If You Let Me).” Black Mafia Life also mined Funkadelic’s “Freak of the Week” for its “Call It What U Want” single featuring 2Pac and Digital Underground’s Money B. Elsewhere, Cold 187um incorporated Parliament’s “Mothership Connection (Star Child)” into Black Mafia Life cut “Pimp Clinic.”

Although it didn’t have a name yet, the sound Above the Law ushered in through Vocally Pimpin’ and Black Mafia Life was later used by one-time collaborator and Ruthless Records labelmate Dr. Dre throughout his massively popular and influential debut album, The Chronic. Like Above the Law before him, Dr. Dre relied on the work of Parliament, Funkadelic, and George Clinton for what would become his album’s signature material.

Dr. Dre’s The Chronic single “__ wit Dre Day (And Everybody’s Celebratin’),” for instance, built its sonics on samples from Funkadelic’s “(Not Just) Knee Deep” and George Clinton’s “Atomic Dog.” The song shares much of the sound of Above the Law’s “Never Missin’ a Beat,” the first cut on Black Mafia Life.

“Let Me Ride,” another The Chronic single, sampled Parliament’s “Mothership Connection (Star Child)” and “Swing Down, Sweet Chariot” in much the same way Above the Law had on Black Mafia Life selection “Pimp Clinic.”

But while Above the Law’s Black Mafia Life scored rap hits with singles “V.S.O.P.” and “Call It What U Want,” the album sold less than five hundred thousand copies. On the other hand, Dr. Dre’s The Chronic sold more than three million copies within a year of its release, becoming one of the bestselling and most influential albums in rap history.

Dr. Dre’s next production project was Snoop Dogg’s debut album, 1993’s Doggystyle. Like The Chronic, it incorporated funk samples and funk elements throughout. It also featured a song called “G Funk Intro,” which gave a name to the sound Above the Law had created with Vocally Pimpin’ and Black Mafia Life and that Dr. Dre popularized with The Chronic.

“This is just a small introduction to the G-Funk era,” Snoop Dogg raps on “G Funk Intro,” which, like The Chronic single “__ wit Dre Day (And Everybody’s Celebratin’),” sampled Funkadelic’s “(Not Just) Knee Deep.” The G-Funk (gangster funk) era was officially underway, indeed, but Dr. Dre’s and Snoop Dogg’s popularity may have overshadowed Above the Law’s innovation because, in rap, the artist who makes something commercially popular is often more revered than the person who created or inspired it.

“They were the originators of G-Funk, period,” Yukmouth said of Above the Law. “N.W.A was on some damn-near Public Enemy shit with their beats. Above the Law came and slowed it down. It was groovy. Us being from the Bay, there’s a lot of pimps, a lot of hustlers, so we like the slowed-down, mob, groovy shit, so we were into Above the Law. It was funky.”

After Above the Law created G-Funk, Dr. Dre popularized it, and Snoop Dogg named it. The next major player in the G-Funk wave was Dr. Dre’s stepbrother, Warren G, who branded the music and became synonymous with it.

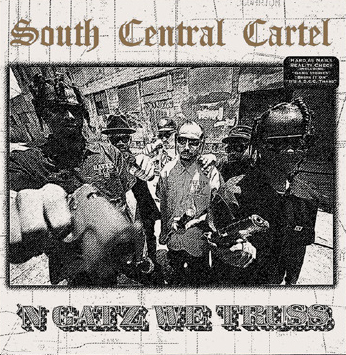

SOUTH CENTRAL’S FINEST

South Central Cartel became the first purely gangster rap act from the West Coast to release a project on one of Russell Simmons’s bevy of labels. The six-member crew released their ’N Gatz We Truss via Rush Associated Labels (RAL) in 1994 and collaborated with Ice-T, MC Eiht, 2Pac, and Spice 1 on the single “Gangsta Team.” Onyx—a rap quartet from Queens, New York, whose Bacdafucup was released by RAL in 1993—and Bo$$—a female gangster rapper from Detroit who released her Born Gangstaz album in 1993 on RAL—were the first gangster rappers to release material via the hip-hop mogul.

Warren G gained notoriety in his Long Beach hometown as one-third of the group 213, which got their name from the original area code of Long Beach and also featured friend Snoop Dogg and fellow Long Beach artist and singer Nate Dogg. As 213 gained popularity in the region, Dr. Dre became familiar with Snoop Dogg’s work through Warren G.

But as Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, and Death Row Records catapulted to super-stardom, Warren G became a supporting act rather than a focal point in the Death Row Records lineup, appearing on the intro of The Chronic selection “Deeez Nuuuts” and rapping on Doggystyle selection “Aint No Fun (If The Homies Cant Have None).”

Unlike his friend and 213 partner in rhyme Snoop Dogg, Warren G didn’t sign with Death Row Records, the imprint co-owned by his stepbrother, Dr. Dre. Instead, Warren G signed with Violator/Rush Associated Labels, sister labels of Def Jam Recordings, the iconic New York rap label that had released such groundbreaking acts as LL Cool J, Beastie Boys, Public Enemy, and Slick Rick.

Warren G had a reason not to sign with Death Row Records. “I didn’t want to be waitin’,” he said. “I wanted people to hear what I had, and I would have had to really wait for Snoop to do his thing. My brother had already did his thing when we did The Chronic, and I didn’t feel like waiting. Dre was like, ‘Warren, you need to go on and be your own man and get out there and do your thing.’ So I was like, ‘Shit.’ It hurt, but I went out and did it.”

After producing and rapping on rapper-singer Mista Grimm’s 1993 song “Indo Smoke,” which was featured on the soundtrack for the 2Pac and Janet Jackson film Poetic Justice, Warren G ironically got his first major exposure through a Death Row Records project. Warren G and Nate Dogg teamed up in 1994 for “Regulate,” the main single from the soundtrack for the 2Pac vehicle Above the Rim, which Death Row Records released in March 1994.

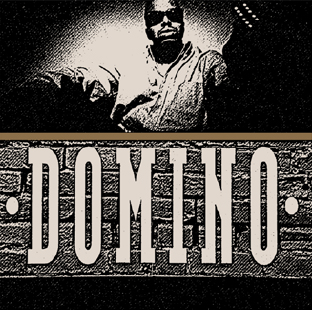

DOMINO

With a singsongy style that was often more R&B than rap, Long Beach rapper-singer Domino broke through in late 1993 with his smash “Getto Jam” single. Both “Getto Jam” and his 1993 self-titled album were certified gold in 1994. The Domino album was primarily produced by DJ Battlecat, a one-time KDAY mixmaster who would later produce material for Snoop Dogg, Kurupt, and Xzibit, among others. DJ Quik affiliate AMG also produced on the project.

Warren G produced “Regulate,” which lifted its velvety groove from Michael McDonald’s “I Keep Forgettin’.” The song’s smooth, laid-back sonics and airy aural atmosphere stood in stark contrast to Warren G’s rhymes about getting robbed at gunpoint for his jewelry. Fortunately for Warren G, Nate Dogg was there to “regulate” the situation by shooting the assailants. After their bodies dropped, Nate Dogg sang in his stoic style about how he and Warren G were able to resume pursuing women. A car full of them agreed to accompany the crooner to the fictitious Eastside Motel.

As the song concludes, Warren G puts his stamp on G-Funk, saying it is “where rhythm is life and life is rhythm.” Nate Dogg follows him by singing, “It’s the G-Funk era, funked out with a gangsta twist.”

Thanks in large part to the massive success of “Regulate,” the Above the Rim soundtrack sold more than one million copies in two months and more than two million copies in less than six months, making it a double-platinum project for Death Row Records. As a single, “Regulate” sold more than one million copies in less than four months, making Warren G’s first single a platinum-certified smash hit and a great launching pad for his solo career.

Released on June 7, 1994, Warren G’s Regulate… G Funk Era branded the wave of gangster rap that Above the Law had been developing for years and that Dr. Dre had popularized through the immense success of his The Chronic album and Snoop Dogg’s subsequent Doggystyle album.

But Regulate… G Funk Era had a much different lyrical tenor than the work of Above the Law, Dr. Dre, and Snoop Dogg. Where the lyrics by those artists were regularly rife with testosterone-filled episodes of a violent life on the streets in which they often played the victor, Warren G took a wistful approach on many of his songs. With “Do You See,” for instance, Warren G rapped about the numbing effect of violence in his neighborhood and how, when Snoop Dogg was incarcerated, he made a decision to stop selling drugs and pursue music in earnest.

On Warren G’s other big hit from Regulate… G Funk Era, “This D.J.,” he rapped over smooth, high-pitched keyboards about playing basketball and heading home once the streetlights came on. He augmented his income by selling weed, but he wasn’t portraying himself as a major baller or drug dealer. Instead, it was a way for him to make money and enjoy the smaller moments in his life. Warren G’s world was “gangster lite,” in a sense, a soft-spoken complement to the gruffer material being made by such musical partners as Nate Dogg and Snoop Dogg.

“Nate brought the gangster melodies to the game,” Warren G said. “Snoop brought the smooth gangster style to the game. They’ve had an incredible impact. I’m the cool type.”

Although Warren G’s musical sensibility wasn’t as harsh, aggressive, and confrontational as the rest of the gangster rap world, he is credited with showcasing a new layer of the experience with a different sound.

“That was just another side of what we brought to the table as far as gangster rap music,” MC Eiht said. “It was still a part of that. You had Above the Law, you had Warren [G], you had Kokane. That was a part of Dr. Dre, Eazy[-E], that straight gangster era that we went through.”

Warren G’s Regulate… G Funk Era was a top-seller, rivaling The Chronic, the more acclaimed and culturally significant release from his stepbrother, Dr. Dre. The album sold more than two million copies in two months and moved an additional one million copies by August 1995.

With a combination of well-known associates, quality music, impeccable timing, and a musical movement people could gravitate toward, Warren G became the flagship G-Funk artist.

“I think Warren G exploded for it because he made it a lane, made it a movement instead of people just doing the music,” Yukmouth said. “He said ‘G-Funk.’ They were screaming that shit in every rap. . . . They capitalized on it. They not only made the brand, made the word, made the movement, but the music. They made classic shit, ‘Regulate,’ one of the best G-Funk beats ever done.”

KMEL

The San Francisco–based radio station was a pivotal player in breaking rap records in the region. In the late eighties, it began playing mix shows, and by the early nineties, the station had some of the most progressive programs on urban radio, including Sway (later of MTV fame) & King Tech’s The Wake Up Show, which played a bevy of independent music and showcased freestyle raps from then-emerging acts such as JAY-Z, Eminem, and Wu-Tang Clan.

While the various practitioners of G-Funk were dominating radio, video, and the sales charts, another gangster rap movement was gaining traction in the San Francisco Bay Area: Mob Music. The divergent Northern California rap scene made its first major mark in the mideighties thanks to Oakland’s Too $hort and his partner in rhyme, Freddy B, who would hawk their homemade—and later customized for consumers—rap tapes on public transit. Soon thereafter, Too $hort became a pioneering rapper from the area who was known not only for his groundbreaking music about the world of pimps, prostitutes, and sex, but who also delivered several socially aware and political songs. His often slow, stripped-down, and sonically spare music contained funk elements thanks to the use of live bass guitar and keyboards, among other things.

Much like Southern California, Northern California was rocked by violence throughout the eighties and early nineties. Even though Southern California was rife with gangs and Northern California was not, it suffered many of the same crime-related travails. In Oakland, where the population was 378,617, there were 140 homicides in 1994.

While the harsh streets of Oakland were the topic of much of Too $hort’s music and helped push him to platinum success at the turn of the nineties, other rappers from the city had different stories to tell. Fellow Oakland act Digital Underground, for instance, delivered a string of popular party rap records, most notably “Doowutchyalike” and “The Humpty Dance,” before introducing their protégé, roadie and dancer 2Pac, as a solo artist. Ice Cube’s cousin Del tha Funkee Homosapien added another thoughtful perspective to the discussion with his stories about the struggles of the everyman trying to survive amid typical life challenges and the crime and chaos enveloping his city.

PAUL STEWART

Starting off as a DJ and record promoter, Los Angeles native Paul Stewart became instrumental in Russell Simmons’s embracement of West Coast artists. With New York rap manager Chris Lighty, Stewart executive-produced Warren G’s Regulate… G Funk Era, which was released on Simmons’s Rush Associated Labels (RAL) imprint. In conjunction with his own PMP company, Stewart signed singer Montell Jordan to RAL, launching a successful career accented by platinum party hit “This Is How We Do It” (1995) and the sensuous single “Let’s Ride” (1998).

About ten miles west of Oakland, San Francisco rapper Paris had cultivated a loyal following that gravitated toward his Black Panthers–inspired messaging and political commentary. Around the same time in Hayward, fifteen miles south of Oakland, Spice 1 was emerging as the San Francisco Bay Area’s preeminent straight-up gangster rapper. His overtly violent rhymes were driven by graphic murder talk on such songs as “187 Proof,” “Trigga Gots No Heart,” and “187 He Wrote.”

Yet Too $hort, Digital Underground, Del tha Funkee Homosapien, and Paris were each capturing different segments of the rap-buying public, with Too $hort having the streets locked down, Digital Underground appealing to the college crowd, Del tha Funkee Homosapien sewing up the skater set, and Paris attracting the revolutionary minded. Even though Too $hort rapped about the world in which gangster rappers existed, he didn’t present himself as a gangster. Instead, he was more focused on money and how crime was crippling his city. Spice 1 was a bona fide gangster rapper, but he was a lone wolf of sorts—albeit a hugely popular one with three gold albums. Unlike most of the gangster rappers in Southern California (Ice-T, Ice Cube) or Compton (Eazy-E, N.W.A, Compton’s Most Wanted, DJ Quik), who were part of a camp of similar artists, Spice 1 was not part of a larger movement of artists that helped sustain either his success or his visibility.

Another set of artists from the area, though, was about to seize the street audience in what would later be christened as the Yay Area. Based in Vallejo (about thirty miles north of San Francisco), E-40 and the Click (E-40’s brother, D-Shot; sister, Suga-T; and cousin B-Legit) began gaining traction in the early nineties thanks to such releases as the Click’s “Mr. Flamboyant” and E-40’s “Captain Save a Hoe” and “Practice Lookin’ Hard.”

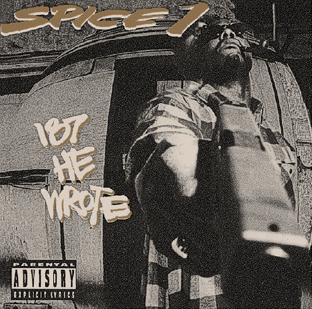

MURDER HE WROTE

Spice 1 made murder his topic of choice throughout his prolific career, as evidenced by such songs as “Money or Murder,” “I’m the Fuckin’ Murderer,” and “The Murda Show.” There was a sizable market for the one-time Jive Records artist’s particular brand of grisly gun talk. Each of the Hayward rapper’s first three albums (1992’s Spice 1, 1993’s 187 He Wrote, and 1994’s AmeriKKKa’s Nightmare) went gold, selling in excess of five hundred thousand units each.

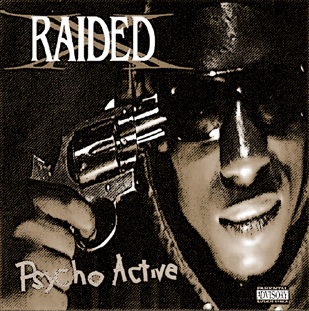

Southern California is often synonymous with gangster rap. Three rappers from the Golden State’s capital have also been among the genre’s most prolific and noteworthy because of their maniacal music and their affiliation with the Garden Blocc Crips. Two of them also have notable arrest records.

X-Raided. The release of the rapper’s debut album, 1992’s Psycho Active, was accompanied by controversy. X-Raided was arrested after authorities said some of the material on the collection described a local murder, and also claimed that the gun X-Raided was holding to his head on the album cover was the actual murder weapon. After his arrest, X-Raided recorded material over the phone while incarcerated. He was convicted of first-degree murder, which was also ruled a gang-related homicide. He was sentenced to thirty-one years to life in prison, and has released more than a dozen albums while incarcerated.

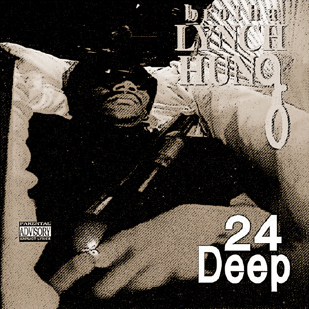

Brotha Lynch Hung. The producer of X-Raided’s Psycho Active album for Black Market Records, Brotha Lynch Hung also signed to the Sacramento imprint, which released his 24 Deep project in 1993. The nine-track collection’s hallmark is the dark, eerie vibe on such selections as the title track, “Back Fade,” and “Fundamentals of Ripgut Cannibalism (Outro).” Black Market signed a distribution deal with Priority Records, bringing Brotha Lynch Hung’s 1995 album, Season of da Siccness, to a national audience. In 2001, he collaborated with C-Bo for the Blocc Movement album. Nine years later, he released the first of his three LPs for Tech N9ne’s Strange Music.

C-Bo. After garnering regional attention in 1994 with his The Autopsy and Gas Chamber projects, C-Bo (who appeared on 2Pac’s All Eyez on Me album) earned national headlines four years later when he was arrested and incarcerated after the state of California determined that the content included on his 1998 ‘Til My Casket Drops album violated the terms of his parole. The terms of C-Bo’s parole included provisions that restricted him from associating with gang members, as well as a stipulation that he would “not engage in any behavior which promotes the gang lifestyle, criminal behavior and/or violence against law enforcement.” ‘Til My Casket Drops song “Deadly Game” includes lyrics about killing a police officer in order to avoid being arrested.

“When ‘Mr. Flamboyant’ came out, it just swept our whole area,” Kansas City rapper Tech N9ne said. “There was nothing like it musically, and E-40 was just giving game in a way that was exciting to the fan no matter how young they were, because some of that game was over the head of the young ones, but the delivery was so new and exciting, and still is today. It sounded like nothing we’d ever heard before.”

“Anything West Coast is just West Coast. . . . We are these type of people that don’t give a fuck. It’s California. It’s West Coast . . .”

MC EIHT

E-40’s and the Click’s blend of street tales—running the gamut from gangster stories and pimp tales to life lessons and business tips—made them more than just gangster rappers. Similar to the G-Funk artists, the way E-40 and the Click rapped wasn’t loud, confrontational, or overtly aggressive like many other gangster rappers of the era.

“E-40 was a gentler kind of gangster rap,” said Leslie “Big Lez” Segar, former host of BET’s Rap City. “I didn’t really feel threatened by anything he said or depicted in his rhymes.”

Furthermore, E-40’s slippery delivery style and his ability to make up words, to flip phrases, and to redefine terms made him instantly identifiable.

“His vernacular and the way he rapped, he rapped like no-fuckin’-body in the Bay Area has ever rapped,” said Yukmouth, who grew up in Oakland, California, about twenty-five miles south of Vallejo. “How quick he is and how sharp he is putting it together has always been the key to his success, and the words he invents from the gate. He was calling the police the ‘Po-po Penelope,’ the ‘Federalis.’ He had lingo and words that we didn’t know. He put that out there and we started rocking with it.”

E-40 pioneered virtually a dictionary’s worth of slang, including fasheezy, adding -izzle to the end of words, and referring to marijuana as “broccoli.”

“E-40 is a trendsetter,” Tech N9ne said. “But his trends never die. His flow is groundbreaking. He has an ear for music.”

Sonically, E-40’s and the Click’s music was also distinctive. It was spearheaded by producers Mike Mosley, who had met E-40 in the streets before they started making music together, and Sam Bostic, a funk and soul musician who had released Circuitry Starring Sam Bostic in 1985 on Atlantic Records. Mosley would play the initial take on the material and then have Bostic come in and replay it, adding another layer of musicianship to the track.

“It was a mixture of me knowing how to produce like a Quincy Jones or like a Dr. Dre, knowing to have somebody come in and give me a certain sound that I need that I couldn’t necessarily play it myself all the way,” Mike Mosley said. “I would play it up to a certain point, and then I would hire this guy to come in [and be like], ‘Hey, play this right here.’ Then he’d replay it and funk it out.”

The Mob Music sound, as it would later be known, was identified by its slow, bass-heavy, groovy, and melodic qualities. “M.O.B.: musically orchestrated basslines,” E-40 said. “It’s a certain sound. It’s gotta be sinister. It’s a sound. It ain’t about a shoot ’em up bang bang or whatever. As long as that bassline’s heavy, or it sounds real eerie and the drums [are] kickin’, [it’s Mob Music]. It’s a feel. That’s what Mob Music is.”

Although the music was coming from Northern California, Los Angeles–area rappers quickly connected with E-40’s and the Click’s sounds and subject matter.

“It was on a different aspect,” MC Eiht said, “but it still was the same G-Funk, synthesizers, heavy basslines, so it wasn’t hard for us to get into the up-north sound.

E-40 surveys the scene on the set of his “Hope I Don’t Go Back” video in Sylmar, California, on May 23, 1998.

“To us, anything West Coast is just West Coast. We know that the brothas from up north get down a little differently than the Southern California dudes as far as the gang situation. But we are these type of people that don’t give a fuck. It’s California. It’s West Coast, and it wasn’t like E-40 was so far from our shit.”

E-40 and the Click also had another advantage in building their fan base. E-40 and B-Legit had attended Grambling State University, a historically black college located about three hundred miles northwest of New Orleans. While there, they performed, promoted, and connected with thousands of fans outside of their hometown in ways that the average independent rappers couldn’t. Thus, when E-40 and the Click began pushing their music, they had two major markets supporting them, the San Francisco Bay Area and the South.

By 1994, E-40 and the Click had released a string of successful singles, albums, and EPs, including E-40’s Mr. Flamboyant EP, The Mail Man EP, and Federal album (which depicts a “Mob” side and a “gangsta” side in the album’s cover art). The Click also released their Let’s Side EP and Down & Dirty album.

Like other business-minded rappers before him, E-40 released his material on his own record label. Sick Wid’ It Records was the recording home for E-40’s music as well as that of the Click. E-40’s entrepreneurial spirit and independent work ethic were celebrated by Northern California rap fans.

“As far as niggas in the street, they was the epitome as far as rap groups,” Yukmouth said. “To have your own record label and to put on your family and to have your own Mob Music, your own production team, that was the ultimate.”

The executives at Jive Records (Whodini, Steady B, Kool Moe Dee, D.J. Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince, Schoolly D, Boogie Down Productions, Too $hort, Spice 1) took notice and signed E-40 and his Sick Wid’ It label to a contract that took both E-40’s and the Click’s success from independent and regional to major label and national.

Locally, E-40’s and Sick Wid’ It’s success helped influence and increase the profile of a legion of independent labels and artists in the San Francisco Bay Area who released their own brand of street-centered, mob- and gangster-inspired music, including In-A-Minute Records (M.C. Pooh, R.B.L. Posse), Strictly Business Records (Mac Dre, Ray Luv), Big League Records (415, Richie Rich), Young Black Brotha Records (Ray Luv, Mac Mall,), and Get Low Records (JT The Bigga Figga, San Quinn).

These acts and their imprints helped make the San Francisco Bay Area the leading locale for independent rap, specifically independent gangster rap. Many of these artists ended up signing national deals after enjoying regional success, including M.C. Pooh (then going as Pooh-Man) with Too $hort’s Dangerous Music and Jive Records, Ray Luv with Atlantic Records, and Richie Rich with Def Jam.

As gangster rap continued expanding in sound, style, and regions, it was about to endure a wave of real-life violence that would cost rap music the lives of two of its most popular and most significant artists.