2Pac and Leslie “Big Lez” Segar.

IN 1994, AMERICA HAD SHOWN IT WAS LARGELY INDIFFERENT TO CULTURAL TRENDS THAT FORESHADOWED SOME OF THE MAJOR EVENTS RESPONSIBLE FOR SHAPING THE COUNTRY IN THE NEXT DECADES.

For many people living outside of New York, the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center was just another news story whose gravity and foreboding went unrecognized. Furthermore, the conviction of the four men charged with the crime barely resonated with a public oblivious to the anti-American sentiment growing throughout the world.

Additionally, Rodney King’s settlement was seen as a far cry from a victory by a population that had witnessed and experienced decades of police brutality. The massive riots that resulted when the police were acquitted on criminal charges caught the public’s attention, but only momentarily.

1996

Key Rap Releases

1. 2Pac’s All Eyez on Me album

2. Fugees’ The Score album

3. Nas’s “If I Ruled the World (Imagine That)” single

US President

Bill Clinton

Something Else

Bill Clinton signed welfare reform into law.

While these events were taking place in courtrooms across the country, the rap world continued to evolve. Death Row Records sustained its commercial and critical dominance with hit albums from Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg, while P. Diddy’s Bad Boy Entertainment emerged as a major player thanks to the success of Craig Mack and the Notorious B.I.G. (aka Biggie or Biggie Smalls). Eazy-E also found success post-N.W.A with his own material, solo projects from MC Ren, and Cleveland rap quintet Bone Thugs-N-Harmony. Despite these successes, however, the rap world was on the brink of a civil war of sorts, one highlighted by real-world violence.

It was seldom discussed, but for years, there was real animosity simmering between rap communities from different cities. Artists who were not from New York, in particular, often felt as though they were being slighted by the New York rap elite, whether it was record labels passing them over, radio disc jockeys Kool DJ Red Alert and Mr. Magic not playing their music, or the rap media (almost all of which was located in New York) dismissing their work. Ironically, though, West Coast rap was dramatically outselling rap from New York artists. But a casual observer—and even studious rap fans who happened to be swayed more by hype than the charts—would never have known it if they lived in New York.

“I think people in general just looked down on the West Coast,” MC Ren said. “Ever since we started coming out back in the day, it was like we were the little stepbrother or something. On the West Coast, it was hard getting respect from people on the East Coast. We know hip-hop started in New York, and back then, it was that feeling like, if you wasn’t from New York, you’re not going to get that respect. It’s been hard since then and it’s hard now.”

As early as 1989, the Geto Boys rapper Willie D articulated this frustration on his group’s “Do It Like a G.O.” single. Willie D lamented the lack of support the Geto Boys’ music was getting on East Coast radio, and called out the egos of New Yorkers in particular.

The explosion in the popularity of and mainstream-media attention given to Los Angeles–area gangster rappers such as Ice-T, Eazy-E, N.W.A, Compton’s Most Wanted, DJ Quik, Cypress Hill, Dr. Dre, and Snoop Dogg had shifted much of the record-buying public’s and the media’s focus away from New York rappers. As the trend continued into 1994, several rappers—even those not from New York—began taking note of how rap had been changing and how it had moved away from its political, or so-called “conscious,” direction, which had been largely spearheaded by New York acts. This was another point of contention, as New York artists were seemingly upset that they had fallen behind, especially commercially, to gangster rappers.

One song that drew the ire of several West Coast acts was Common’s 1994 single “i used to love h.e.r.” (The “h.e.r.” is short for “hearing every rhyme.”) The song traces Common’s relationship with rap, which is the “girl” he’s rapping about. In the second verse, the Chicago rapper (who went by Common Sense at the time) said it was cool that she went to the West Coast and that he “wasn’t salty she was with the boys in the hood,” a reference to either Eazy-E’s 1987 landmark single or the 1991 film starring Ice Cube—or both.

In the third verse, though, Common laments how his girl is now

A gangsta rollin’ with gangsta bitches / Always smokin’ blunts and gettin’ drunk / Tellin’ me sad stories, now she only fucks with the funk

By the time “i used to love h.e.r.” was released in September 1994, the robust gangster rap industry had become synonymous with the West Coast. Through such West Coast acts as Cypress Hill, among others, rap had become associated with smoking weed, blunts in particular. Then, of course, there was the West Coast’s obvious affinity for funk music and funk samples, as well as its burgeoning G-Funk movement.

As much as Common’s “i used to love h.e.r.” rankled some West Coast acts, the animosity between artists from different regions exploded after 2Pac was shot five times on November 30, 1994, while going to meet the Notorious B.I.G. at Quad Recording Studios in New York. Prior to that, 2Pac and the Notorious B.I.G., a Brooklyn rapper signed to P. Diddy’s Bad Boy Entertainment, had become friends. Even though 2Pac was born in New York and went to high school in Baltimore, he rose to national prominence after relocating to the San Francisco Bay Area and becoming a member of Oakland-based rap group Digital Underground. He started off as a dancer and a roadie, touring with the outfit as their crossover songs “Doowutchyalike” and “The Humpty Dance” became major hits in 1989.

YOU AIN’T GANGSTA?!?

Growing up in the Mid-City section of Los Angeles in the 1980s, Murs was affected by the same violence and gangbanging that enveloped the more famous sections of the city’s metropolitan area, such as Compton, Watts, and South Central. Like many of his friends, he grew up listening to such local heroes as Eazy-E and DJ Quik, but Murs didn’t want to make gangster rap. He was met with resistance when he embarked upon a nongangster rap recording career in the mid–nineteen nineties. Even the success of early nongangster rap acts the Pharcyde, Freestyle Fellowship, and Tha Alkaholiks did little to alter people’s perception of what Los Angeles rap was supposed to sound like.

“LA was ready for it, but I don’t think the East Coast was ready for it,” Murs said. “Where I experienced the most problems was trying to get outside of LA because people would say, ‘No. LA’s not that.’ In LA, people knew what you were. It wasn’t accepted and it wasn’t cool, but you had a place thanks to Unity, Rap Pages, Rap Sheet. That was the place for the Ras Kasses and the Western Hemispheres. It wasn’t as big as the gangster rap scene and it wasn’t as valid or respected, but it was there. Outside of LA, no hope.”

In 1991, 2Pac appeared on Digital Underground’s energetic, playful “Same Song” single and released his first album, the incendiary 2Pacalypse Now. The collection’s most celebrated cut was “Brenda’s Got a Baby,” a somber tale about a twelve-year-old girl who gets pregnant by her cousin, throws the newborn in the trash, and gets killed after becoming a prostitute. But much of 2Pacalypse Now focused on his disdain for police and how they often abused their authority, especially when dealing with young black men.

Also a trained actor, 2Pac became an in-demand Hollywood player thanks to his dramatic turn as the troubled Bishop in the 1992 film Juice. Obsessed with power, his character turns on his friends, ultimately dying during an altercation with one of them. 2Pac’s star continued its ascent in 1993 with the release of his Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z. album (which contained the hits “Keep Ya Head Up” and “I Get Around”) and his appearance in director John Singleton’s Poetic Justice opposite Janet Jackson.

But 2Pac’s success was tempered by his increasingly serious legal issues. He was arrested six times between 1993 and when he was shot on November 30, 1994. While recuperating from his gunshot wounds, 2Pac was on trial for sexually abusing a woman. Wheelchair bound in court, on February 7, 1995, he was sentenced to one and a half to four and a half years in prison for the crime.

Later that month, the Notorious B.I.G. released a single titled “Who Shot Ya?” Although it did not directly reference 2Pac or the shooting, it was, at the least, bad timing and poor judgment to release a song called “Who Shot Ya?” while 2Pac—an alleged friend—was healing from wounds he suffered on a trip to visit Biggie. Biggie claimed the song had nothing to do with 2Pac getting shot. Regardless, the song made it appear as though something was awry between the two.

In the April 1995 issue of Vibe (which hit newsstands in March), 2Pac implicated former friend the Notorious B.I.G. and P. Diddy in his shooting, saying that they set him up to get robbed, beaten, and shot.

The article, according to former Vibe features editor Rob Kenner, “marked the first time Biggie had any idea Tupac—who was formerly a close friend—had problems with him. Our decision to change the names of two of the people in the story, both because they were not public figures but rather ‘street dudes’ and because we could not verify the things 2Pac was alleging about them, would come under fire in years to come.”

Several films and documentaries about the Notorious B.I.G. and 2Pac have been made. Here are some of the more noteworthy releases.

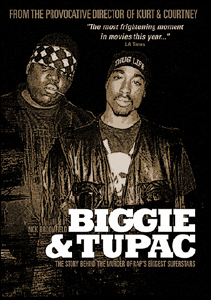

Biggie & Tupac (2002). This documentary film garnered media attention given director Nick Broom-field’s pedigree (Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer, Kurt & Courtney) but was derided for its lack of definitive findings regarding the murders of the rap stars despite a series of accusations that are implied but never confirmed.

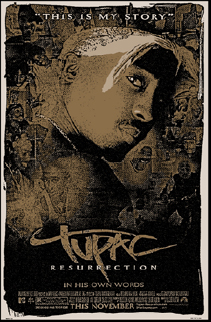

Tupac: Resurrection (2003). This Academy Award–nominated film uses home movies, photographs, and 2Pac’s own voice to tell the story of the late artist’s life.

Notorious (2009). This biopic details the Notorious B.I.G.’s Brooklyn, New York, upbringing and his rise to rap superstardom.

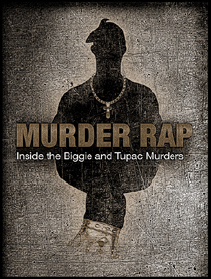

Murder Rap: Inside the Biggie and Tupac Murders (2015). This documentary is anchored by the work of retired LAPD detective Greg Kading. The film purports that the killers of both Biggie and 2Pac are not unknown. Rather, Kading says, they are simply unprosecuted because key witnesses are dead, among other factors.

All Eyez on Me (2017). Helmed by longtime video director Benny Boom, the 2Pac biopic features Demetrius Shipp Jr. starring as the late rapper and actor.

Unsolved: The Murders of Tupac & The Notorious B.I.G. (2018). This television series focuses on the travails of detectives Greg Kading and Russell Poole, among others, who worked to solve the high-profile murders of the superstar rappers.

As well intentioned as Kenner’s statement may have been, it failed to address other journalistic shortcomings on Vibe’s part.

The publication had given 2Pac a platform to make explosive and unsubstantiated claims that were never corroborated by any research or secondary follow-up. To be fair, plenty of responsibility rests on the artists, who both ratcheted up the controversy with their actions, but Vibe failed in its journalistic responsibility when it neglected to notify the Notorious B.I.G. and P. Diddy about the article and its content prior to its publication. This lapse in journalistic judgment added significant fuel to the fire that eventually consumed both 2Pac and the Notorious B.I.G.

Despite rap’s massive popularity in 1994, the mainstream media was still relatively reluctant to give rap much coverage. Moreover, the Internet as we know it did not yet exist, which made publications that covered rap, such as Vibe and the Source, the go-to places for information on the rap world, whether it was an album review, a story about a trend in the music, or an interview with an artist. Consequently, had the more established and respected news outlets regularly carried interviews with 2Pac and the rapidly growing rap industry, they would have likely done a more balanced job reporting on 2Pac, his allegations, and the situation regarding his shooting. If nothing else, the mainstream media typically had stricter journalistic standards.

But that didn’t happen. Animosity began ramping up elsewhere, too, as Ice Cube protégé Mack 10 included the song “Westside Slaughterhouse” on his self-titled album, which was released in June 1995. The song featured Mack 10, Ice Cube, and WC blasting Common and the stance he took on “i used to love h.e.r.” Ice Cube, in particular, took aim at Common and the mindset adopted by artists who felt gangster rap wasn’t a valid segment of the genre.

All you suckas wanna diss the Pacific / But you busta niggas never get specific / Used to love her, mad ’cause we fucked her / Pussy-whipped bitch with no common sense / Hip-hop started in the West / Ice Cube bailin’ through the East without a vest

If “Westside Slaughterhouse” served as a warning shot about the deepening animosity between acts from the East and West Coasts, entities from both sides crossed a line months later at the Source Awards, which were held at Madison Square Garden’s Paramount Theatre in New York. Broadcast on August 3, 1995, the event featured a number of moments that showed the disdain that people from different rap regions held for one another.

While on stage accepting Above the Rim’s award for Best Motion Picture Soundtrack, Death Row Records’ Suge Knight took the first shot at P. Diddy, who had become famous for appearing on the songs and in the videos of his artists and the artists he worked with. “Any artist out there [that] wanna be an artist, and wanna stay a star and won’t have to worry about the executive producer trying to be all in the videos, all on the records, dancing, come to Death Row,” Knight said.

“Once Suge said what he said, I knew right from there this was gonna keep going,” said rapper and the Source executive Raymond “Benzino” Scott. “I didn’t know it was going to go to the extent that it did, but at the end, you didn’t see Suge and Puff hugging. Suge had over one hundred people in the audience. All from L.A. Gangbangers. I don’t think New York really grasped the whole thing about gangbanging until that time. You had Bloods and Crips sitting in New York City, and I think that was the first time that was taking place.”

But Suge’s comment wasn’t the only sore spot revealed at the event. When Snoop Dogg—far and away the bestselling and most popular rapper at the time—took the stage, he was greeted by a chorus of boos from the largely New York audience. “The East Coast don’t love Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg?” he responded with obvious disappointment, disgust, and disdain. “The East Coast ain’t got no love for Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg and Death Row? Y’all don’t love us?”

While on stage, P. Diddy made a point to brush aside Knight’s comments. “I’m the executive producer that comment was made about a little bit earlier,” P. Diddy said. “Contrary to what other people may feel, I would like to say that I’m very proud of Dr. Dre, of Death Row and Suge Knight for their accomplishments. And all this East and West, that need to stop.”

OutKast was booed after winning Best New Artist, as the New York crowd seemed unimpressed with the emerging duo from Atlanta, showing that Willie D’s 1989 statements on “Do It Like a G.O.” were warranted. But OutKast’s André 3000 took the high road when accepting the award, saying, “The South got somethin’ to say.”

The fallout from the Source Awards was swift, deadly, and dramatic. On September 23, 1995, Jai Hassan-Jamal Robles, a Death Row Records employee, was shot and killed in an Atlanta nightclub. Robles had been arguing with P. Diddy’s employee and bodyguard Anthony “Wolf” Jones before he was shot. Neither P. Diddy nor any of his associates were questioned about the shooting by Atlanta police.

When Eazy-E died of complications due to AIDS in 1995, the rap world was in a state of shock. HIV/AIDS was an emerging epidemic at the time, one that had yet to take the life of a high profile heterosexual male.

The N.W.A mastermind’s death ran counter to the gangster rap image. Eazy-E didn’t die by the gun, but because of a medical condition.

“I think if he would have died in a gang fight or a beef somewhere, it probably would have been easier to take almost, as far as his legacy is concerned,” said Cold 187um, lead rapper and producer of Above The Law, which released three albums and an EP on Eazy-E’s Ruthless Records. “Being an ex-Compton gangbanger, an ex-drug dealer, if he got caught up in a fight in the streets, it’d be like, ‘Oh. He went out like a G,’ verses it being a health thing. At that point, we thought only gay people could get that. We weren’t thinking a hip-hop artist as manly as an Eazy-E [could].”

Given that the mainstream media largely overlooked rap until the late nineties, the rap press had a virtual monopoly on coverage. Below are several of the prominent rap magazines from the nineties and notable facts about each.

The Source. Founded by Harvard students, The Source grew from a newsletter to the most prominent rap publication. At one point, the New York–based publication outsold Rolling Stone on newsstands.

Vibe. Founded by producer Quincy Jones, the magazine positioned itself more as an urban culture magazine than a straight-up rap publication.

Rap Sheet. The Los Angeles–area publication was printed on newspaper yet packaged as a magazine.

Rap Pages. Owned by porn magnate Larry Flynt, the magazine focused on covering emerging, underground, and independent rappers, as well as rappers from the West Coast and South.

Murder Dog. The San Francisco Bay Area–based magazine featured Q&As with and album reviews of mostly independent gangster rappers from the West Coast, South, and Midwest.

XXL. Launched in 1997, the magazine made an early name for itself with its split covers, making two different covers of the same magazine for several of its first issues. It put New York’s JAY-Z on one cover and New Orleans’s Master P on a second cover of its first issue, for instance, in order to target two key, and distinctly different, demographics of the rap-buying public: the East Coast and the South.

Then, in October 1995, Death Row Records duo Tha Dogg Pound (Daz and Kurupt) released Dogg Food, including their song “New York, New York.” The song was innocuous enough, but its video was anything but. In the clip from the video, Tha Dogg Pound and Snoop Dogg (who rapped the chorus) are shown to be as tall as the city’s skyscrapers. In one scene, Snoop Dogg kicks over a building. In another, a shoe is shown stepping on a car, crushing it. On top of that, while the Death Row Records crew was in New York filming the video, the trailers housing them were shot at.

Also in October 1995, 2Pac was released from prison and joined Death Row Records after the label posted $1.4 million bail to free him. At the time, he appeared optimistic about the future.

“It’s been stress and drama for a long time now, man,” 2Pac said. “So much has happened. I got shot five times by some dudes who were trying to rub me out. But God is great. He let me come back. But, when I look at the last few years, it’s not like everybody just did me wrong. I made some mistakes. But I’m ready to move on.”

Dr. Dre, though, was also moving on. In March 1996, he left Death Row Records, just three months after collaborating and producing 2Pac’s “California Love,” the song that catapulted 2Pac to rap’s forefront. Dr. Dre gave his share of the company to Knight and founded his own company, Aftermath Entertainment, which, like Death Row, would be backed by longtime partner Jimmy Iovine’s Interscope Records.

March 1996 proved to be a pivotal month for other reasons, too. 2Pac let everyone know that he hadn’t totally left everything in the past when he confronted the Notorious B.I.G. and P. Diddy at the Soul Train Awards. While Biggie and his entourage were backstage waiting for their ride, 2Pac and Knight pulled up in a Hummer and started yelling at them. The situation was defused by security and others and ended when Biggie and his crew got in their vehicle and left.

Then, in June, 2Pac released the song “Hit ’Em Up,” in which he claimed to have had sex with Biggie’s estranged wife, R&B singer and fellow Bad Boy Entertainment recording artist Faith Evans. He also dissed East Coast rappers Junior M.A.F.I.A., Mobb Deep, and Chino XL on the song’s outro, showing that his animosity now went beyond just Biggie.

Even with all the friction with some of its rappers, 2Pac had long made it clear that he had no problem with the entire East Coast, a position he reaffirmed in “Hit ’Em Up.” “Now when I came out, I told you it was just about Biggie,” he said in the song’s outro. “Then everybody had to open their mouth with a motherfuckin’ opinion.”

In addition to singling out the people he had problems with on “Hit ’Em Up,” 2Pac was also trying to defuse the situation by working with other East Coast artists, including Big Daddy Kane and Nice & Smooth on the unreleased album One Nation.

2PAC’S ONE NATION ALBUM

During the height of the so-called East Coast–West Coast beef, 2pac was recording One Nation with artists from the East Coast. He flew New York rap groups Black Moon and Smif-N-Wessun out to his Calabasas home about thirty miles northwest of Los Angeles. Big Daddy Kane and Nice & Smooth were also among the New York acts with whom 2Pac worked on the album, which he wanted to use as evidence that he had nothing against rappers from New York in general.

The media, though, didn’t run with that story. In the midst of this controversy, hip-hop journals largely ignored the integration of the two coasts on rap projects. In 1995, Los Angeles’s King Tee protégés Tha Alkaholiks worked with New York producer Diamond D for the group’s second album, titled Coast II Coast. At the same time, some of the bestselling and most acclaimed albums in hip-hop history, from LL Cool J’s Bigger and Deffer to Ice Cube’s AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, featured New Yorkers teaming with Los Angeles artists.

In August 1996, the rivalry between the coasts was officially branded when Vibe used the headline “East vs. West: Biggie & Puffy Break Their Silence” on the cover of its September 1996 issue. The following month, on September 7, after a series of back-and-forth exchanges on songs and in interviews, 2Pac was gunned down in Las Vegas by a still-unidentified assailant brandishing a .40-caliber Glock. He was hit four times, twice in the chest, once in the arm, and once in the thigh. The news traveled fast.

2Pac friend and collaborator Snoop Dogg was at Warren G’s house when he started getting calls and pages urging him to turn on the news. After seeing that 2Pac had been shot, Snoop immediately sprang into action.

“I drove down there to the hospital ’cause I wanted to see my nigga, make sure he was straight,” Snoop Dogg said. “I’m thinking he was gonna make it.”

Snoop Dogg said he was able to speak with 2Pac in the hospital. “I had said a little prayer to him in his head and held his hand and whispered at him, said my peace with him,” Snoop Dogg said. “He didn’t have no consciousness, but I felt like my spirit and his spirit connected, and I felt like he got it.”

2Pac held on for six days in the hospital but ultimately succumbed to his injuries and died on September 13, 1996. He was twenty-five years old.

Eminem recalled hearing about 2Pac’s death while working as a cook at a sports bar. “A lot of people that worked at the job that I worked at didn’t understand 2Pac or didn’t understand the music, so [they] were looking at us like, ‘What’s wrong? What’s the big deal? Get over it,’” Eminem said. “It’s like, ‘Nah.’ This is a really fucked up day. For the longest, I think anybody who had something to do with hip-hop and loved the music, it was a sense of mourning for a long time.”

Members of the Vibe staff say they felt partially responsible for the situation escalating and resulting in 2Pac’s death, though several of them have differing takes on how “East vs. West” ended up on the cover of the publication. Features editor Rob Kenner, editor Carter Harris, and writer Larry “Blackspot” Hester say they were against it. Editor in chief Alan Light said several people were involved in the decision.

As rap developed on the East and West Coasts in the eighties and early nineties, the Midwest was developing its own gangster rap style. The Legendary Traxster, who produced defining mid- and late nineties Chicago gangster rap material from Do or Die, Twista, Snypaz, and Psychodrama, among others, was influenced by the sonics coming from the West Coast, while the rappers Traxster and other beatsmiths worked with drew more inspiration from the flair and undulating flows of East Coast rappers.

Chicago gangster rappers also separated themselves by blatantly shouting out the Windy City’s swath of prominent gangs, including the Gangster Disciples, Black Disciples, and Vice Lords, almost as soon as they started making music.

“A lot of those stories and a lot of that gangster rap was directly linked to the gang culture, whereas West Coast hip-hop, if you look at its origins, even though it was related to gangbanging, it wasn’t as blatant as ours,” Traxster said. “We were saying ‘GDs,’ ‘BDs.’ We were naming out the gangs and claiming the gangs. Early West Coast hip-hop, we didn’t know if Eazy was a Crip or a Blood. Affiliations weren’t really portrayed through the music. Tha Dogg Pound was Tha Dogg Pound, but it took a while before we figured out they were Crips. Eventually they said it. From the beginning with us, it was, ‘Vice Lords.’ If you listen to Crucial Conflict’s [1996 song] ‘To the Left,’ it was actual gangbanging on the record, naming the sets. I think that played a big part of what made Chicago gangster rap unique. It wasn’t just about being a gangster. It was about being a member of a gang.”

Although Twista enjoyed platinum success, and Do or Die and Crucial Conflict hit gold, Chicago gangster rap failed to become a bigger movement because, at least in part, there wasn’t the same drive surrounding the artists as there had been with, say, rappers from Compton or acts signed to Ruthless Records or Death Row Records.

“In the nineties, it was really dominated by Twista, Do or Die, and a few other local groups, but it wasn’t like now, where there was a new group coming out every week and being recognized,” Traxster said. “The output of Chicago wasn’t high enough. It’s almost like we didn’t understand that flooding the market and stimulating the market by encouraging other companies and other acts would benefit us by creating a bigger market.”

IT’S A COMPTON (RECORD-BUYING) THANG

When record stores were the primary way fans purchased music, rap consumers in Compton were particularly prone to support local talent. “It was the realness of what our artists spoke about and the flavor of the beat,” says Arnold “Bigg A” White, who, with his brother, owned and operated Underworld Records & Tapes at 2530 E. Alondra Boulevard in Compton from 1995 to 2001. “Any artist, from DJ Quik to Eazy-E to Ice-T to King Tee to CMW, everybody was talking about what’s happening on the West [Coast], the lifestyle, the lowriders, police brutality, the dress code. With the stories that they were telling, the majority of the consumer base knew somebody that knew somebody who knew somebody, so there was always that surge of energy to come in there and support. I remember when Compton was hot. Once Eazy and them broke, everybody was looking for anything from Compton. It kind of transferred to Long Beach when Death Row kicked in when Dre went over there and got Snoop and them. Everybody from Long Beach got deals, so that’s what we were on.”

“Other editors were involved in that,” Light said. “I’m not gonna say that I know who’s the one who made the decision. It was all being debated and discussed. These are collaborative enterprises. It’s not a question of one person dictating what it’s gonna be.”

Light says that Keith Clinkscales, Vibe’s founding president and CEO, and Gilbert Rogin, Vibe’s editorial director, wanted “East vs. West” on the cover. “Was it on the cover? Yes,” Clinkscales said. “Did I approve it? No. But the reality of the situation is that I didn’t approve the cover in most cases. The editor approves the covers. Because of the nature of that cover, it is quite natural that I would have been involved in it except for the fact that I was going to Los Angeles. Ultimately, the mistake I made was not making sure I saw the final proof. I’m proud of the story. Proud of the job Blackspot did. Proud of the editing that was done. I’m not proud of that cover line.”

As rap was reeling from the death of 2Pac, a new supergroup released their debut album. Westside Connection (Ice Cube, Mack 10, and WC) united for Bow Down, a scathing indictment of gangster rap’s detractors, especially those in New York. The thirteen-track project featured title song “Bow Down,” a warning to people who doubted gangster rap; “Gangstas Make the World Go Round,” a testament to the potency of gangsters; and “All the Critics in New York,” a message that each rapper was tired of being disrespected by New York rap critics.

“When Bow Down came out, it shut everything down in my eyes,” said Dave Weiner, who worked at Priority Records, which released the album, from 1991 to 1999. “To me, Cube was one of the best shit-talkers, obviously with ‘No Vaseline’ being one of the hardest diss tracks in hip-hop history. He brought that same level of anger to Bow Down, the same level of aggressiveness. They talked shit about everybody and everything having to do with the West Coast being the Best Coast. You couldn’t deny it when that record came out. If it wasn’t as hard as we all thought it was, it would have just gotten laughed at and would have been removed from any part of the story, but it lived up to what we all hoped for representing the West Coast. It made us proud.”

By January 1997, Westside Connection had sold one million copies of Bow Down, good for a platinum plaque. The LP’s success illustrated that fans identified with Westside Connection’s perspective that artists from the West Coast had been marginalized by rap’s New York–based gatekeepers.

With tensions running high in the rap world, the echo of 2Pac’s murder had not yet quieted when the Notorious B.I.G. traveled to Los Angeles to promote his forthcoming second album, Life After Death. After attending a Vibe magazine party at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles, the rapper was leaving in his SUV. The vehicle—hired to drive him around for the night—was stopped at a traffic light when a car pulled up beside it. A man opened fire, and Biggie was hit four times. He was pronounced dead an hour later. Like 2Pac’s murder, the murder of the Notorious B.I.G. remains unsolved.

After the deaths of two of rap’s marquee acts, there was a definite sense of unease throughout every level of the rap business.

“You had cats on the West Coast that didn’t want to go to the East Coast and you had people on the East Coast that didn’t want to come to the West Coast,” MC Ren said. “It was just a time where you had to be careful. You just couldn’t do like you used to do. You couldn’t just go anywhere. It was like a gang war, damn near, basically going on. Two coasts going at each other like how fools bang in the street. It was just a bad time.”

Priority Records, which had helped make gangster rap a national phenomenon in the eighties and early nineties with Eazy-E, N.W.A, and Ice Cube, was in the midst of ramping up security in its office due to internal issues with its own artists and others by the time 2Pac and the Notorious B.I.G. were killed.

The label didn’t shy away from signing gangster rappers, but it took drastic measures to attempt to ensure the safety of its employees. It installed a bulletproof entrance, which resembled the entrance to a bank vault, at its office in the CNN building on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles. The company also hired off-duty LAPD officers, who were housed in a secret office in the CNN building, to escort employees considered “high risk” due to either their status at the company or their relationships with artists. These employees weren’t allowed to leave the office without alerting one of the officers.

“There was so much chaos and so much drama on all fronts in hip-hop that that was obviously the pinnacle, but it wasn’t the only thing,” said the Priority Records employee Weiner. “There was constant drama, constant chaos with our artists within and artists trying to get at Priority Records. It shut us down when that shit happened. It wasn’t like, ‘Oh my God, this shit happened and now we have to take these measures.’ It was more like what was expected. The reality. No one was surprised.”

Similarly, the lack of journalistic integrity was not lost on those within the rap community, who realized after reading Vibe’s interviews with 2Pac and the Notorious B.I.G. that Vibe was not delivering a true journalistic service to its readers.

“They weren’t speaking to each other,” Brooklyn rapper Talib Kweli said. “They were reading the magazines. Then, ’Pac got shot. Big goes to an after-party at Vibe magazine and gets killed in front of all those people. That’s not to single out Vibe magazine. I’m just saying the media in general is just real responsible for inflaming a lot of that shit.

“When B.I.G. took that picture, he didn’t take that picture thinking ‘East vs. West.’ He took a picture thinking, ‘I’m going to be on the cover of Vibe.’”

METHOD MAN

“If the media would have had some responsibility,” Kweli continued, “and been like, ‘Listen, cut that shit out. We can’t condone that activity,’ instead of glorifying it, which would have made sense and been the logical, responsible thing to do especially if you say, ‘I’m a media institution that represents hip-hop.’ I expect that from a Newsweek or a Time or somebody that doesn’t claim to represent hip-hop. But magazines and media outlets that say, ‘We represent hip-hop and are all about hip-hop,’ and are doing nothing but exploiting the shit when the shit was obviously a dangerous situation.”

Regardless of who made the decision to print 2Pac’s unsubstantiated claims without fact-checking them or to put “East vs. West” on the cover, the fact that no one at Vibe realized putting those words in the magazine or on the cover would be inflammatory, at the least, is unfathomable and unjustifiable.

“With that East–West crap, Vibe has to take a lot of . . . they should’ve got a bullet,” said Method Man, the Wu-Tang Clan member who recorded with both 2Pac and the Notorious B.I.G., appearing on 2Pac’s All Eyez on Me album and Biggie’s Ready to Die. “They should’ve got a bullet instead of ’Pac or B.I.G. When they put that cover up with B.I.G. and Puff on there, when B.I.G. took that picture, he didn’t take that picture thinking ‘East vs. West.’ He took a picture thinking, ‘I’m going to be on the cover of Vibe.’ What came after is what solidified [the] East–West beef for all the dumb motherfuckers around that don’t know how to think for themselves. Maybe they just don’t like West Coast people. Maybe they just don’t like East Coast people, but that fueled the fire. . . . ’Pac even said himself, ‘You guys injected yourselves into a beef that was just between me and Bad Boy [Entertainment].’ Had nothing to do with nobody else. He said it himself.”

In the aftermath of the deaths of two of rap’s biggest figures, every segment of the rap community found itself in mourning.

“People on the West Coast weren’t happy when Biggie got killed, and people on the East Coast weren’t happy when ’Pac got killed,” Weiner said. “I never saw or heard anything like that. I never heard anyone celebrating those losses, which at the end of the day, to me, really let you know what was going on with the community. It [showed] hip-hop is based on a culture that challenges itself and everything around it, and when it came to the real shit happening, everyone stood up together and felt that loss.

“It made people realize that they went too far,” Weiner added. “It made the fans, the entire community of hip-hop, realize that this shit-talking, this beef that we’ve all documented, been a part of, and seen develop over the years, can get out of hand.”

Still, as the fallout from the deaths of 2Pac and the Notorious B.I.G. lingered, gangster rap was about to be transformed by a revolutionary artist who changed the business of rap and who brought the streets to the dance floor.