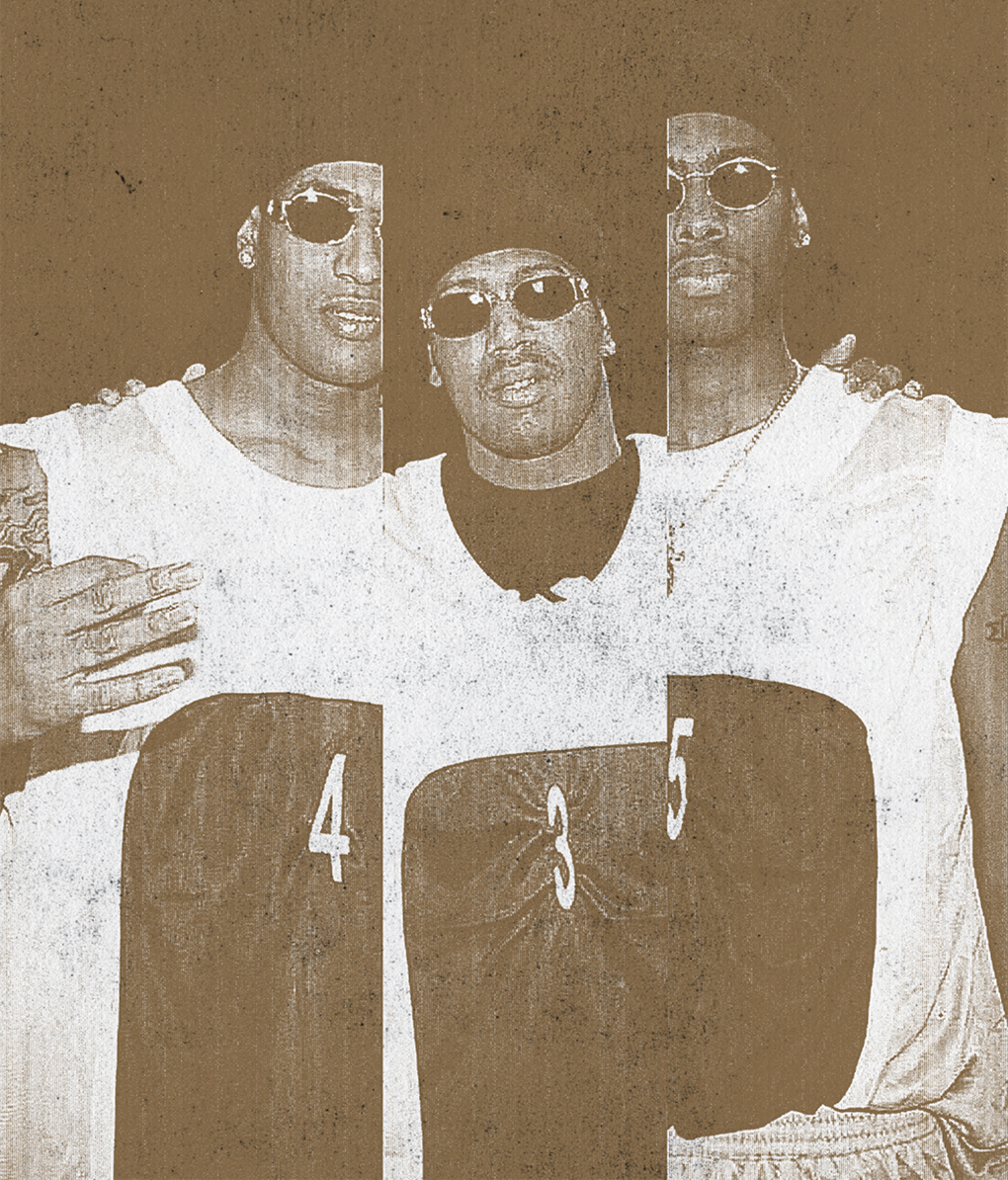

From left: Brothers C-Murder, Master P, and Silkk the Shocker were three of No Limit Records’ platinum artists. They are shown here at the Sickle Cell Celebrity Jam III at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena on February 28, 1998.

IN 1997, THE WORLD TOOK STEPS TO REIN ITSELF IN FROM GRIEVOUS SELF-INFLICTED WOUNDS.

Countries that had signed an agreement at the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993 started outlawing the production, stockpiling, and use of chemical weapons. Delegates from one hundred and fifty nations met in Kyoto, Japan, and reached an agreement to control heat-trapping greenhouse gases. In Hong Kong, chickens were slaughtered in an attempt to prevent and limit the outbreak of H5N1, avian influenza, also known as the bird flu.

As pockets of the world tried to clean up these issues, rap was undergoing a similar process. The genre was reeling from the deaths of 2Pac and the Notorious B.I.G., and there was an unspoken agreement that something needed to change in the culture. The much-needed adjustment came from an unlikely force that rose to prominence and was aided by a familiar partner.

1997

Key Rap Releases

1. The Notorious B.I.G.’s Life After Death album

2. Puff Daddy & The Family’s “I’ll Be Missing You” single

3. Master P’s Ghetto D album

US President

Bill Clinton

Something Else

Steve Jobs was named Apple’s interim CEO.

Back in February 1995, Dave Weiner, then a Priority Records sales rep, had taken a business trip to Oakland, California, to visit Music People’s 1-Stop. At the time, Music People’s was what was known as a one-stop, a business that bought albums and singles on vinyl, CD, and cassette from record companies. One-stops such as Music People’s would then sell the products to the independent record stores in the region.

Weiner, who started at Priority Records in the mailroom in 1991 and had worked his way up through the sales department, had taken the trip to sell Priority projects to Music People’s, namely mainstays such as N.W.A and Ice Cube. He wasn’t going to find talent or to add to Priority Records’ roster, but the course of rap history was dramatically transformed due to a chance encounter in the Music People’s parking lot.

On the way to his car, Weiner was approached by an emerging artist. It was Percy Robert Miller, aka Master P. Since he was in the business of independent rap music, Weiner was familiar with Master P and his fledgling No Limit Records, which had been making a dent in the San Francisco Bay Area’s flourishing indie rap scene.

Master P handed Weiner a copy of his 99 Ways to Die project and told him where it would be charting on the Billboard charts the following week. Impressed by P’s confidence and knowledge of the business, Weiner took the rapper-businessman’s information, along with the copy of 99 Ways to Die.

The following week, Master P’s 99 Ways to Die debuted one slot lower than P had predicted. “My mind was blown [by the fact] that he accomplished that without any real assistance,” Weiner said.

Master P and No Limit Records’ success with 99 Ways to Die gave Weiner an idea. Once implemented, the idea revolutionized the music industry and made Priority Records more money than it had ever made with rap industry titans N.W.A and Ice Cube.

Weiner’s idea was to have Priority Records distribute the releases of other record companies via its own distribution deal with CEMA (Capitol Records, EMI Records, Manhattan Records, and Angel Records), starting with No Limit Records. At the time, Priority Records was the only self-owned independent distributor of rap music in the United States. Prior to launching Priority Records, owners Bryan Turner and Mark Cerami both worked at compilation label K-Tel. While at K-Tel, Turner worked in A&R, putting the music portion of the albums together. Cerami, meanwhile, handled sales.

The industry standard was that the record company would send an album, single, or EP to its distributor, who would then manufacture it and ship it to retail. Upon receipt of the music, the retailer would then pay the distributor, who would then pay the label.

Through his work, though, Cerami had developed strong relationships with all the national music business accounts and wanted to sell Priority Records projects to the chain record stores, one-stops, and other businesses directly. Thus, Cerami set it up so Priority Records would manufacture and ship its material to retail, and the retailers, in turn, would pay Priority Records for the product. This was a major asset given that the labels controlled the majority of the shelf space in all the record stores, meaning that there was limited real estate on which to stock albums.

In addition to cutting out a step in the business process, Priority Records also had another distinct advantage: Its receivables were guaranteed by its manufacturer/distributor, CEMA. This meant that if Priority Records sold one hundred thousand copies of an album to retail that it would get paid full price for those one hundred thousand albums because of the massive clout that CEMA had with retailers. In return, CEMA received a small distribution fee. Without this relationship, Priority would have most likely suffered the fate of other small labels: chase retailers to get paid, get paid long after the money was due, and pay a premium on manufacturing their products.

Thus, Priority Records was, in effect, both its own national distributor and an independent record label. Unlike any other record company, Priority was set up so that it could sign an artist or label to a distribution deal itself since it could facilitate its own distribution needs.

Like Master P, Three 6 Mafia got their start in the mid-1990s releasing music independently before exploding nationally. The Memphis sextet (DJ Paul, Juicy J, Gangsta Boo, Lord Infamous, Crunchy Black, Koopsta Knicca) broke through in 1997 thanks to their hit “Tear Da Club Up ‘97” single and nationally released Chpt. 2 “World Domination” album, which went gold in nine months.

Although the group’s wicked sonics (courtesy of DJ Paul and Juicy J) and gruff lyrics were inspired by N.W.A, Three 6 Mafia added a different wrinkle to gangster rap. “Our gangster was blended with some dark, wicked shit, 666 Mafia type shit,” Gangsta Boo says. “Before our arrival, Memphis wasn’t really nothing like that. Memphis was just all gangster. But when we brought the gangster with a bit of wickedness, it was like, ‘Motherfucka, not only will we kill you, but we will kill you and burn your body. Then, when we burn your body, we’ll have a fuckin’ ritual with your bones. After we do that, we’re going to go home and smoke a blunt.’”

This arrangement was the reason Weiner could suggest the idea for Priority Records to partner with Master P’s No Limit and offer it distribution. Priority was already set up to implement that type of arrangement, one that was best-suited to its internal workings given that neither Turner nor Cerami was a devout rap fan with his finger on the pulse of the rap scene.

“Priority Records was never designed to be a hip-hop label,” Weiner said. “They were doing compilations, which led to the California Raisins, which led to the financing that brought on N.W.A.”

After those initial successes, Priority Records had other hits in signing and developing its own acts, most notably Ice Cube and Mack 10, but the company had yet to become a marquee destination for talent. Given Weiner’s knowledge of Priority Records’ structure and Master P’s independent success, Weiner took his concept to his boss, Priority Records cofounder Mark Cerami.

“Priority Records was never designed to be a hip-hop label. They were doing compilations, which led to the California Raisins, which led to the financing that brought on N.W.A.”

DAVE WEINER

Cerami understood Weiner’s vision and agreed to sign Master P and No Limit Records to a groundbreaking deal. Master P got $250,000 and retained 100 percent ownership of his master recordings, as well as his publishing. Priority Records got the exclusive manufacturing/distribution rights and took a distribution fee in order to guarantee getting No Limit product into stores.

“There was no record company that was offering national distribution deals without taking a[n ownership] percentage of that opportunity,” said Weiner, who was the freshly minted director of distributed labels at Priority Records when Priority signed Master P’s No Limit Records. “It was the first deal of its kind where he got an advance and we took no publishing, no masters, and only took a distribution fee. Simple as that.”

Priority Records reissued 99 Ways to Die in June 1995. The following month, it released True from No Limit group TRU, whose core members were Master P and two of his younger brothers, Silkk the Shocker and C-Murder.

Now with Priority Records’ national reach and more money to invest, No Limit Records began gaining new fans and getting exposure at retail, in magazines, on television, and on radio. It also had its first hit with “I’m Bout It, Bout It,” a song that referenced Master P’s New Orleans roots and his then–home base of Richmond, California, about twelve miles north of Oakland.

Like E-40, who was from Vallejo in the San Francisco Bay Area and went to school at Grambling State University in Louisiana, Master P had ready-made fan bases on the West Coast and in the South. Once No Limit Records’ music started taking off, this geographical benefit helped bolster his ascent to stardom.

Taking advantage of this rare cross-regional opportunity, in October 1995, Master P released Bouncin’ and Swingin’, a compilation from the Down South Hustlers. In reality, the Down South Hustlers was not a group but a name No Limit used to push the double-disc album, which featured gangster or gangster-leaning rap artists from several cities around the country, including Flint, Michigan (the Dayton Family); Memphis (8Ball & MJG); Port Arthur, Texas (UGK); Houston (E.S.G.); and, of course, its own No Limit Records acts from New Orleans (Silkk the Shocker, Mia X, C-Murder). The album proved to be a shrewd marketing move. No Limit was able to gain fans in cities throughout the country who supported any one of the more than twenty artists who were featured on the twenty-six-track project.

As would become standard practice with No Limit Records, Master P began flooding record stores with his company’s material. In April 1996, he scored a significant hit with his Ice Cream Man album and its “Mr. Ice Cream Man” single. By September, the album had sold more than five hundred thousand units, demonstrating that Master P’s acumen, Weiner’s vision, and Cerami’s faith were all being rewarded handsomely.

But with little—yet steadily increasing—national radio play and video support, getting No Limit albums in stores was still somewhat difficult, even with the label’s early sales victories and Priority Records’ decade of delivering consistently popular projects. Having longstanding relationships with the buyers at retail was one of the main reasons why Priority Records’ unique positioning as both a record company and a record distributor was so critical to its sustained success.

“Accounts didn’t really know how to deal with rap music, especially the chains,” Weiner said. “So it was very important to have your own sales staff go out there and explain what Westside Connection was, explain what No Limit was, and explain why Silkk the Shocker needed to ship two hundred thousand units. That wouldn’t have happened through a major label sales rep, who would not have understood what we were working on. That was a key part of the puzzle, sales guys that knew how to move hip-hop.”

Master P rose to national prominence through his No Limit Records. The New Orleans native also paved the way in several key business areas.

I’m bout it. Master P’s 1997 landmark direct-to-video film jumpstarted a new industry (independent rap flicks) and showed Hollywood that it could move major units even if films bypassed theaters.

Dimension Films. Master P became the first rapper to release his own movie through a major film production partner. His I Got the Hook-Up project was released May 27, 1998, by Dimension Films in conjunction with his own No Limit.

Converse. In 1999, Converse made Master P the first rapper to have his own shoe. Yes, other rappers had had endorsement deals with shoe companies prior to Master P’s pact—most notably Run-DMC with Adidas—but those rappers didn’t have their own shoes.

No Limit Sports. Master P was the first rapper to have his own sports agency. It pulled a major coup by signing running back Ricky Williams, who was drafted No. 5 by the New Orleans Saints in 1999. However, the athlete’s incentive-based contract caused a black eye from which the agency never recovered.

At this time, in the early stages of No Limit’s rise to national prominence, the combination of Master P and No Limit Records’ Southern slang and attitude; the imprint’s often garish album covers; and the keyboard, funk, and G-Funk production of such San Francisco Bay Area producers as Al Eaton and K-Lou, among others, provided a new twist on gangster rap. As artists, Master P and the No Limit roster were combining Southern sensibilities over decidedly West Coast–sounding production. The combination proved addictive, with Master P and the growing No Limit Records lineup becoming street favorites thanks to their gruff, violent, and profanity-filled rhymes about coming up in the ghetto, hustling, and trying to make it out by any means necessary. But where other artists were revered for their lyricism, toughness, or production, Master P and his No Limit Records acts garnered respect because of their ability to hustle, to grind, and to make catchy music with memorable choruses.

Through this early work, Master P was building his brand and setting up his next major move. Industry veterans began noticing his momentum.

“You snatch the streets first,” said MC Eiht, Compton’s Most Wanted’s front man and gold-selling solo artist. “Make the streets respect you. ‘Yeah, I sold my dope.’ That’s why he got so much respect from that angle, because he came with the ‘I started off from the bottom with y’all, too.’ But when he got that [money] and he was able to start selling them records, he turned into the music dude, like, ‘Everything ain’t finna just be about dope and motherfuckin’ hustling in the projects. Shit’s finna be about making the crowd move.’ That’s why the shit transitioned, which was smart.”

As he was laying his music empire’s foundation, Master P was also transitioning in other ways. In the second half of 1996, he began shooting his debut feature film, I’m bout it, which he financed himself. Master P approached Priority Records to distribute the film.

“When he brought the concept of films and I’m bout it, none of us knew what to make of it,” Weiner said.

Weiner told Master P that Priority was a record company. “Well, you’re about to be a film company,” Weiner recalled Master P saying to him. Master P urged Priority Records’ sales staff to work with the same people at Tower Records, Warehouse, and Music Plus who bought albums from them. When P was told the people who bought movies at record stores were not the same people who bought albums, he was undeterred.

“He wouldn’t take no for an answer,” Weiner said. “He said, ‘Well, then sell it to your music buyer.’ Well, it’s a video. It’s a movie. We can’t sell it to our music buyer. He said, ‘You have to. They know who I am. They know the value of Master P.’ We all looked at each other and said, ‘He’s got a point. Let’s see if we can actually do this.’”

Thanks to Master P’s insistence, Priority Records’ sales staff pushed Master P’s I’m bout it film through unorthodox channels (music people selling a movie to film people). The results were remarkable. I’m bout it sold more than five hundred thousand units according to Weiner. For perspective, the 2000 film How the Grinch Stole Christmas, starring Hollywood elite Jim Carrey and directed by the revered Ron Howard, was released on VHS in October 2001. It sold 1.4 million copies by the end of the year, meaning that Master P’s I’m bout it sold about a third of the number of copies as a film made by major Hollywood players sold—for a fraction of the cost.

The success of I’m bout it was about more than money and sales, though. “I think it was solely responsible for showing independent filmmakers that you could circumvent Hollywood, put your film out, recoup your film, make some money, and move on to the next film,” Weiner said. “That had never been done before through the channels that we went [through].”

Other rappers quickly understood the significance of Master P’s business savvy.

“You’ve got to open up different avenues to people that ain’t really checkin’ for us or don’t really know nothing about us,” said Mack 10, the Inglewood, California, rapper and Westside Connection member who appeared in I’m bout it. “I’m bout it opened up a lot of doors for Master P, man. Somebody might see that and give one of them niggas that’s in the movie a role in a major movie, or we might sell more records to people that didn’t used to buy our records.”

A bevy of rappers followed Master P’s lead and released their own direct-to-video movies. Below are some of the more noteworthy projects.

Streets Is Watching. JAY-Z’s 1998 film featured a number of music videos interwoven into the movie’s narrative.

Thicker Than Water. Mack 10’s 1999 film traces the lives of rival gang leaders who are trying to break into the music business.

Charlie Hustle: The Blueprint of a Self-Made Millionaire. E-40’s 1999 film featured appearances from a number of rappers and athletes, including Gary Payton and Kurupt.

Baller Blockin’. Cash Money Records’ 2000 film was a dramatized depiction of the lives of the rappers on the label, including Lil Wayne, Birdman, Juvenile, and B.G.

Choices: The Movie. Three 6 Mafia’s 2001 film focused on the life of an ex-con trying to balance right and wrong as he assimilates back into society.

By the time Master P’s Ghetto D album arrived in record stores in September 1997, Master P and No Limit Records had become a bona fide movement. Fans had bought into the No Limit mystique and were now buying the label’s releases as soon as they came out, often without even hearing a single from the album. Buoyed by this momentum, Ghetto D entered the Billboard Top 200 charts at No. 1, signaling Master P’s rise to the top of both the rap and music worlds.

Growing up in Hollywood, Florida, about twenty miles north of Miami, ¡Mayday! rapper Wrekonize was in seventh grade when Master P and No Limit’s popularity exploded. Even though he gravitated toward the music of such New York rap acts as De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, and Gang Starr, and typically wasn’t drawn to keyboard-driven production, he was drawn to No Limit’s music, Master P’s up-tempo “Make Em’ Say Uhh!” single, in particular. It was, in essence, feel-good gangster rap that was also danceable.

“The whole No Limit movement swept through Broward County like heavy, heavy,” Wrekonize said. “Even though Florida is such a different place than the rest of the South, we still get a lot of our influence from the South. When ‘Make Em’ Say Uhh!’ came out, that changed everything. Our whole high school started bumping the No Limit stuff. P brought such a creative spin on it that all the things that I thought I was stubborn about in terms of my musical taste were out the window. I was bumpin’ P’s shit, Mystikal’s shit, Silkk the Shocker’s shit. [Master P] brought such a creative spin that I didn’t expect in the music. It spoke to us in that time and that area, for sure.”

With a No. 1 album, a direct-to-video movie selling hundreds of thousands of units, and No Limit albums from Mia X (Unlady Like) and TRU (Tru 2 da Game) selling in excess of five hundred thousand units within months of their respective releases, Master P and No Limit Records blindsided the music industry.

Priority Records had been enjoying significant success at the time with Westside Connection’s platinum Bow Down album and Mack 10’s eponymous debut album, which had gone gold. Yet No Limit became Priority’s priority, with Master P as the label’s mastermind.

“Many of Priority Records’ employees and artists were actually slow to understand and hesitant to embrace the magnitude of Master P’s moves.”

DAVE WEINER

“He consumed us,” Weiner said. “His movement happened so fast that it went from a quiet operation to just trying to keep up.”

Many of Priority Records’ employees and artists were actually slow to understand and hesitant to embrace the magnitude of Master P’s moves.

“There was a period when I first signed Master P where he got no love from [Ice] Cube and some of the other artists on the label,” said Weiner, who ran a four-person department at the beginning of his distribution run with No Limit. “They didn’t understand him or his music, and he was the little guy in the company. He got the cold shoulder. When No Limit exploded, the tables turned and all of the sudden he was the big guy in the company and everybody else was trying to do something with No Limit. He flipped the whole company on its head over the course of a couple of years and turned a staff of two hundred that didn’t want to work on his records, that didn’t want to help, that didn’t want to be a part of it, to those two hundred people doing everything they could to get involved because they missed the boat.”

Master P stands as one of the best marketers in rap history. After college, the New Orleans native relocated to Richmond, California, and launched his own No Limit record store and record company. He quickly realized how an eye-popping album cover would help move his independently released music.

What started off as crudely designed homages to life on the streets evolved into imaginatively garish album art that was supplied by Photoshop wizards Pen & Pixel.

Let’s revisit several of the most memorable No Limit album covers in all their glory.

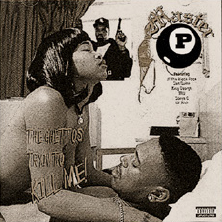

The Ghettos Tryin’ to Kill Me! by Master P (1994). Master P’s first significant foray into album art shock and awe comes from one of the last albums he released before signing with Priority Records. On this memorable cover, he has a woman on top of him seemingly participating in sex, which understandably has Master P’s full attention. Unfortunately for the rapping businessman, there is an angry-looking man brandishing a firearm seemingly about to come through the bedroom window. Was it a ruse? Did the woman set him up, luring him with sex to set up a robbery? Or was Master P saying that he needed security at all times, even when he was having sex because the ghetto was tryin’ to kill him? If truly great art is in the eye of the beholder, then the cover art of The Ghettos Tryin’ to Kill Me! is a masterpiece.

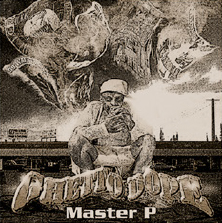

Ghetto Dope by Master P (1997). As Master P and his No Limit Records began enjoying increasing success throughout the midnineties, the execution of his entire operation improved, from his beats (now supplied from percussive production team Beats By the Pound) to his raps, as well as the caliber of his collaborators. This success also led to bigger budgets for his album art. With the album that announced his arrival as a national star, Master P wanted to hit hard. So, for his then-titled Ghetto Dope album art, he featured a man who appeared to be a drug addict smoking what appeared to be crack. But upon closer inspection of the smoke emanating from the purported crack vial, the “dope” the addict was smoking was actually music from the No Limit Records catalog. Perhaps not coincidentally, the cover of The Ghettos Tryin’ to Kill Me! is one of the images included in the haze.

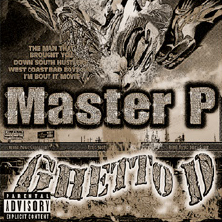

Ghetto D by Master P (1997). Master P was all about the dollar. So, with his stock rising exponentially in the late 1990s, he didn’t want to do anything to hurt his brand—or his chance to move product. Thus, he changed the name of his Ghetto Dope album to Ghetto D. But, when Wal-Mart (which only sold clean versions of albums) and other retailers balked at carrying the original album cover featuring what appeared to be a man smoking crack, Master P revamped the cover art. Gone were the man and the purported crack consumption. In their place was an image featuring a raging flame in front of the No Limit Music Super Store. The smoke still featured the cover art of several No Limit Records albums. With Wal-Mart and others appeased, Ghetto D was the No. 1 album in the country its first full week in stores.

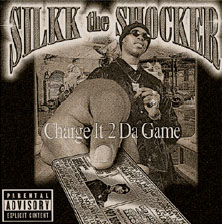

Charge It 2 Da Game by Silkk the Shocker (1998). Master P gave his family members a piece of the No Limit pie. Silkk the Shocker, one of his younger brothers, was the most commercially successful. Silkk’s biggest song was “It Ain’t My Fault,” a collaboration with the rapid-fire, tsunami-like rapper Mystikal. The cut was included on Silkk’s second studio album, Charge It 2 Da Game. As potent as “It Ain’t My Fault” was, the album’s cover became the stuff of street legends. On the image, Silkk sports stylish black shades, blinding jewelry, and a bosslike cigar. But it’s what in his right hand that sets him apart. He’s carrying a personalized Ghetto Express card, the epitome of ghetto fabulousness (had it been real, of course). Silkk’s smirk and the ingenious double entendre of both the album title and the album art showed that Silkk and the No Limit team had panache in spades.

There’s One in Every Family by Fiend (1998). Not to be outdone by Master P’s original Ghetto Dope album cover, gruff-voiced No Limit Records rapper Fiend played off his stage name when crafting his debut No Limit release. There’s One in Every Family was more than just a title. It was a motto people would use to describe the member of their family who was the black sheep. Naturally, Fiend was placed on his album cover at what appeared to be a drug market. With Fiend’s focus on his flip phone as a zombielike drug addict lunged toward him, the rapper’s nonchalance in the face of potential terror was either a chilling or hilarious commentary about this segment of life on the streets, depending on your perspective. Fiend rode the album cover, as well as guest appearances from Master P and Snoop Dogg, to gold album status for There’s One In Every Family.

Rear End by Mercedes (1999). Master P’s No Limit Records was a male-dominated operation. Mia X earned a gold album for 1997’s Unlady Like, but beyond Mia, No Limit didn’t produce a noteworthy female act. It wasn’t for lack of effort, though, especially on the album cover front. Mercedes’s debut album, Rear End, featured the rapper-singer in the background of the cover art holding a smoking cigar. But it was the foreground that stood out. This image of Mercedes featured her bent over what appeared to be a Mercedes-Benz wearing a revealing, form-fitting bikini as she looked back at the camera. Songs such as “Pu**y,” “Kiss Da Cat,” and “N’s Ain’t S**t” were balanced with her thanks yous in the liner notes, which started off with, “First and foremost I would like to thank God, for through him all things are possible.”

No Limit Records had actually become bigger and more lucrative than Priority Records. An avalanche of albums from No Limit Records acts hit record stores in 1997 and the first half of 1998, with Master P and his artists Mia X, Silkk the Shocker, Mystikal, Fiend, Kane & Abel, and C-Murder all going gold or platinum and branding themselves as “No Limit Soldiers.” Their signature look was to dress in military fatigues for press shots, album artwork, and in their videos.

But the military imagery was more than just motif. It extended to actual confrontation, as evidenced by the No Limit policy of boxing to solve interpersonal issues. They were literally mandated to fight through their problems. “Whoever wanna get the gloves—I don’t care if you the president of the company or you clean up the office—if you feel you wanna get it in, then that’s how we do,” Master P said. “It take all the fear away. When you don’t have no fear, you can be a better person in life.”

The fearless attitude, combined with the military image and mentality, became the No Limit lifestyle. “He’s always had this military-inspired approach, and that’s how he built the company, with lieutenants and colonels,” Weiner said. “People were appointed positions, and they followed it.

“You weren’t allowed to be tired,” Weiner added. “You weren’t allowed to say, ‘Yo, I need to catch a night’s rest.’ That’d be showing weakness. He led by example. He didn’t sit in his hotel room and call shots. He was at every meeting, every appointment, every editing session, every recording session. I don’t think he slept.”

The onslaught of music and uniformity in presentation made an impression with young fans. “I could see the cohesive image and branding they had,” Wrekonize said. “It was the way that they presented themselves, the way their colors matched. Just the imagery in itself was so unifying that it made you want to be a part of it. I was super drawn to it even before I knew what it was. In retrospect, I’m like, ‘Man, they had such a cohesive brand image for the whole crew.’ It’s hard to look at it and not want to be a part of that.”

The cohesive No Limit nature carried over to the imprint’s production, which came to be handled by Beats by the Pound, which was made up of KLC, Mo B. Dick, Craig B, and O’Dell. The collective was churning out a massive amount of music, as Master P wanted to give his listeners their money’s worth. His compilations and albums were each typically nearly eighty minutes long, the maximum amount of time that could be held on a CD. He was also a pioneer of the double-disc project, regularly releasing dual-disc compilations and albums.

“He was relentless,” Weiner said. “He had a twenty-one-hour-a-day work ethic. He just wouldn’t stop until he accomplished his goal. That’s where I learned my lesson in the industry that as much as it’s all about the talent, you need the right guide behind the talent to help steer the ship, and those are the ones that are hard to find.”

Master P is one of the preeminent rap moguls. Several other rappers who predated Master P also made impressive business moves. Here’s a breakdown of several rappers who are moguls but who often don’t get the credit for it.

Ice-T. Through his Rhyme Syndicate collective, which included both record company and management arms, Ice-T was one of rap’s early talent scouts and executives. The company managed and released material by such respected and accomplished artists as King Tee (one of the first prominent rappers from Compton), Everlast (later part of House of Pain, famous for the anthemic single “Jump Around”), and WC (also a member of Low Profile and Westside Connection, as well as the front man of the Maad Circle, of which Coolio was also a member).

Eazy-E. The Compton rapper’s Ruthless Records was home to such significant rap acts as J.J. Fad, N.W.A, the D.O.C., Above the Law, MC Ren, and Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, as well as R&B singer Michel’le. Eazy-E also struck deals with multiple labels for his acts, an unprecedented move that prevented him from being beholden to any one company as an outlet for his artists. In 1990, he started selling wares on the inside of his releases, jump-starting and planting the seeds for the rap clothing line explosion that took place in the nineties.

EPMD. The Long Island, New York, duo of Erick Sermon and Parrish Smith were among the first artists to make funk music their sonic backbone. They also were among the best talent scouts in rap history, launching the careers of K-Solo, whose signature was spelling words in his raps; Redman, a dazzlingly creative wordsmith and storyteller; Das EFX, a distinctive duo whose penchant for adding “iggity” and gibberish to some of their rhymes influenced dozens of artists, including Ice Cube; and Keith Murray, whose use of long, peculiar words made him distinctive. (Murray was released under Sermon’s sole tutelage after EPMD split temporarily after their 1992 album, Business Never Personal.)

Ice Cube. After leaving N.W.A, Ice Cube launched his own Lench Mob Records and Street Knowledge Productions, music companies that released acclaimed albums from female rapper Yo-Yo, political rapper Kam, indie rap darling (and Ice Cube’s cousin) Del tha Funkee Homosapien, rap trio Kausion, street rapper K-Dee, rap supergroup Westside Connection, and Westside Connection member WC. Ice Cube’s Cube Vision film and television production company has become one of Hollywood’s most bankable singles, releasing blockbuster franchises that include Next Friday (though not Friday, the first film in the series), Barbershop, Are We There Yet?, and Ride Along.

Master P’s next act showed that as hardworking as he was, he was also fearless. He set his sights on acquiring an established marquee talent, namely Snoop Dogg, the preeminent gangster rapper of the nineties. Since 1996, Snoop Dogg had suffered through the departure of mentor Dr. Dre from Death Row Records, the death of friend and labelmate 2Pac, and the lukewarm response to his second album, Tha Doggfather. Furthermore, Death Row Records owner Suge Knight was incarcerated for being involved in a beating in Las Vegas that took place the night 2Pac was fatally shot. Knight had also developed a reputation for handling his business in gangster ways and was likely the most feared music executive.

As Snoop Dogg toured the country in 1997 in support of Tha Doggfather, he was letting people know that he wanted to leave Death Row Records. But given the turnover at the label and Knight being incarcerated, Snoop Dogg’s future was uncertain. Master P, though, had his own pedigree on the streets and was willing to take any potential heat for bringing Snoop Dogg to No Limit. The move did not sit well with Knight and led to Death Row Records employees and artists targeting Snoop Dogg and No Limit members in public and on record, as well as confronting them at awards shows, concerts, and while traveling. Beyond the sheer audacity of taking Snoop Dogg from the most gangster record company in the country, Master P’s acquisition of Snoop Dogg showed how powerful he’d become in the music world.

“It was one of the most significant moments in West Coast hip-hop in my opinion, because no one out there would challenge Suge,” Weiner said. “When P decided he was going to roll out the red carpet for Snoop, Bryan Turner got on a plane and flew up and saw Suge and said something like, ‘Hey, man, I got nothing to do with this,’ because he was scared. In other words, Snoop was supposed to be untouchable when Suge was in jail. Bryan didn’t want it to even look like he had anything to do with it, because P was making the move on Snoop and doing it with his chest out and nuts swinging and not a care in the world. He wasn’t scared of [Suge]. He wasn’t worried about him.”

Even though it was one of No Limit’s bestselling releases and it showed Snoop Dogg was still one of rap’s preeminent stars, Snoop Dogg’s first album for No Limit Records, August 1998’s Da Game Is to Be Sold, Not to Be Told, was not well-received by many of his West Coast fans, who didn’t appreciate Snoop Dogg rapping almost exclusively over overtly Southern soundscapes from Beats by the Pound and collaborating mostly with No Limit acts.

“It was a turning point,” Weiner said. “I guess you could say that it was definitely a changing of the guards is what it felt like. It was the rise of No Limit and the fall of Death Row at that point. It was pretty clear to us that we had taken that position in the game. We were now larger than Priority. We had now eclipsed what was left of Death Row, and now we had the No. 1 living artist on Death Row at the time over on No Limit. It was surreal.”

Snoop Dogg’s star power coupled with juggernaut Master P helped Da Game Is to Be Sold, Not to Be Told move more than two million copies, rarified territory for virtually any musician. But Snoop Dogg could tell that he needed to rework his music on his next project.

“Snoop, being the man he is, explained that he needed to do something to make it right,” Weiner said. “P, also being a man, said, ‘All right. I understand that,’ and supported that process and put that second record out, which got everything back on track with the No Limit stamp.”

For his follow-up album, May 1999’s No Limit Top Dogg, Snoop Dogg secured beats from DJ Quik and reconnected with Dr. Dre, a monumental move for Snoop Dogg, one fans had been clamoring for since Dr. Dre left Death Row Records in 1996. Dr. Dre produced three No Limit Top Dogg songs, including hard-hitting lead single “B Please,” which also featured Xzibit and Nate Dogg. “B Please,” as well as “Down 4 My N’s”—a muscular, riotous single featuring No Limit labelmates C-Murder and Magic and produced by Beats by the Pound member KLC—signaled Snoop Dogg’s reemergence to the elite level of respect within the rap community. Fans and critics alike loved that Snoop Dogg was delivering gritty and gruff gangster rap full of attitude, urgency, and menace.

Having creative freedom was something Snoop Dogg appreciated. “It’s whoever I want to work with,” Snoop Dogg said. “If I choose not to work with No Limit, [Master P] ain’t got no problem with that. He just wants the best product, and that’s what I’m trying to give him. I felt that working with these producers and these artists was where my heart was at, where I wanted to be on this record. Everybody in the South understands that and knows what time it is, and they’re down with me regardless, because that’s the best Snoop Dogg—when he’s comfortable. They only want the best Snoop Dogg, regardless of who he’s with. It’s still No Limit.”

After the 1996 release of Westside Connection’s chest-thumping Bow Down album—on which Ice Cube, Mack 10, and WC proclaimed the West Coast’s dominance of the rap scene and their disdain for the New York–based rap critics, artists, and DJs who dismissed West Coast rap—Mack 10 wanted to help rap heal. The genre had just endured the murders of 2Pac and the Notorious B.I.G., and the rap community was feeling the effects of the so-called East Coast vs. West Coast beef. So Mack 10 reached out to artists from around the United States to appear on his 1998 album, The Recipe. New York rappers Fat Joe, Big Pun, Foxy Brown, and Ol’ Dirty Bastard appeared on the project, which Fat Joe said was noteworthy. “We want to be known as pioneers of actually taking the step—not just talking shit about it—of bringing the East and West Coasts together,” he said.

The willingness to let Snoop Dogg cater to his audience, and not the Southern and Midwestern fan base that drove No Limit’s success, showed Master P’s keen understanding of rap’s regionalism, even among its bestselling artists. It was also a nod to his ability to make the most of his position, something Priority Records executive Dave Weiner said other rappers didn’t do.

“They didn’t see the business opportunity,” Weiner said. “They were artists. He probably didn’t get the opportunities that Cube and Mack and some of the other artists received coming from the South and coming from the Bay. He probably was forced to put his own music out, which in turn showed him the business model, showed him where the value was, how he could retain his master, retain his publishing, and control and own.

“I’m not mad when people say I’m not really a rapper. They right. I’m a hustler, a businessman. Who wanna be a rapper but ain’t got no money?”

MASTER P

“I take great pride in the fact that Master P was more of a businessman than he was an incredible artist,” Weiner added. “It showed people that hard work, quality work ethic, and not taking no for an answer sometimes meant more than the music itself. So I think a lot of people looked at Master P and No Limit and said, ‘Yo, if that dude made it happen to the level he made it happen, I can do that.’ It felt attainable. It didn’t feel like something that separated him from the average guy out there.”

Master P seemed ambivalent about whether or not he was respected as an artist. “I’m not mad when people say I’m not really a rapper,” he said. “They right. I’m a hustler, a businessman. Who wanna be a rapper on all these TV shows and magazines but ain’t got no money? That’s somebody that need to work on their fundamentals. Me? I’m more a realist than a rapper.”

Master P’s and No Limit’s success helped open doors for several other independent Southern and gangster rap labels and crews who were enjoying their own levels of success around the same time, including Suave House Records (the Houston-based company anchored by 8Ball & MJG); Prophet Entertainment and Hypnotize Minds (the Memphis-based companies anchored by Three 6 Mafia); and Cash Money Records (the New Orleans–based company anchored by B.G., Juvenile, and later, Lil Wayne, Drake, and Nicki Minaj).

“He, in my eyes, inspired a whole movement of independents, because if Master P could do it, anybody could do it, and the ones who went out and worked hard succeeded,” Weiner said. “The ones who thought it was easy and a quick hustle learned the hard way.”

Gangster rap’s next wave built on the momentum Master P started with the Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre reunion. It also placed gangster rap on a platform it had yet to experience.