CHAPTER TWO

The Man from Lancashire

During the 1890s James began to develop a stage act based on comic songs and a clownish appearance, working the free and easies on Fridays and Saturdays. These were described by Dan Leno, ‘the archetype of the modern stand-up comedian’, who had also performed in them. The audiences, he recalled, were drunk by six o’clock, and, if they didn’t like the act, ‘pitiless’. The performer could expect an assortment of missiles, from vegetables to dead rats, to be hurled at him. Not so ‘free and easy’. Presumably James, as Leno had done in London, slept at a lodging house or wherever he could.

In 1896 his Assignments Book, with all the agreement letters for songs he had bought pasted into it, scrapbook fashion, shows that he was already, at the age of twenty, buying and collecting songs. Between April and November he bought half-singing rights to five songs – two of them in deals conducted in the Painter’s Arms in Old-street, Ashton under Lyne, and another in the Dog and Partridge in nearby Stockport. The first in the book, dated 31 August 1896, is written on the back of a printed ‘Memorandum’, the letterhead proclaiming that it came from: ‘Orrell and Formby, Eccentric Comedians and Burlesque Dancers.’ Its subtitle was: ‘The Original Madmen. Success everywhere.’ He was investing in his stage career and running it as a business.

Already he had taken ‘George Formby’ as his stage name. ‘George’ seems to have been a tribute to George Robey, the great music hall comedian and star, who had shown interest in him when he was in the Brothers Glenray. For his surname, the usual story is that he chose the Lancashire place name he had seen on the side of a railway truck, because no one else in the business was called Formby and it would identify him immediately. If that was the case, it worked. Eliza said he chose the name because it ‘flowed’, and because he bore in mind ‘the shorter the name the bigger the letters’ on the posters. But Orrell is also a local place name, suggesting that the two men wanted from the beginning to publicise their Lancastrian roots. This distinctive ‘northernness’ became George’s ‘unique selling point’.

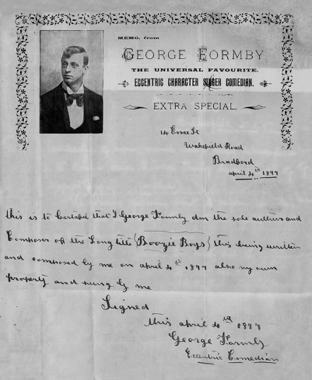

The following year, 1897, Denis J. (Denny) Clarke, proprietor of the Argyle Theatre, Birkenhead, found George performing in the singing room of the Hen and Chickens, Manchester. That year the young singer acquired rights to another nine songs – one by Ernest Dukinfield, his sometime pianist – and composed another, ‘Boogie Boys’, himself. His new ‘Memo’ letterhead, complete with a portrait photograph of him in wing-collared evening dress (and with no mention of Orrell), described him as: ‘The Universal Favourite. Eccentric Character Singer comedian. Extra Special.’ The image of urbane elegance and sophistication he projected was completely at odds with his beaten-up stage persona and a striking forerunner of his son’s equally immaculate theatre appearance three decades later. Clarke offered him £2 a week to sing at his hall, and the two became lifelong friends. Some say that Clarke chose his stage name because at this time the young singer was illiterate. However, several assignment letters are written in a distinctive, artistic, even flowery, hand remarkably similar to the one appearing in his professional engagement diary. His spelling was sometimes inaccurate but his writing hand was mature. Eliza proudly described it as, ‘Plain and distinct. Self-taught entirely.’

Who was Orrell?

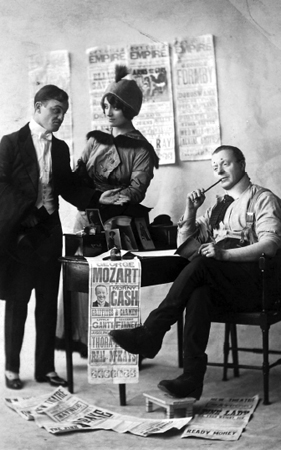

George Formby senior’s writing paper, 1897

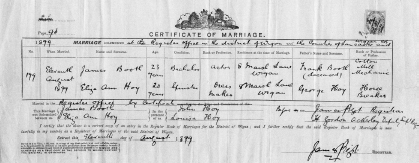

The name George Formby first appeared on a playbill in Birkenhead in 1897. Around this time Walford Bodie, ‘The Electrical Wizard of the North’ and highly successful music hall star, signed George as a comedian in his Royal Magnets show at the Lyceum Theatre, Blackburn, with a forty-week tour to follow. He was offered 30s. a week plus expenses, and this, he said later, ‘was my first rise in life’. It was when he was playing the Wigan Empire during that tour in 1898 that George met nineteen-year-old Eliza Ann Hoy. Her mother was employed there as a cashier. It was a tiny place, according to Eliza, with its entrance off the Market Square. She also worked at the Empire as a dressmaker and took the tickets for the dress circle – ‘pennies for the gallery’, as her son Ted later described it. Formby asked her if she knew where he could find digs. Attracted to him, she gave the address of her parents, who were at that time taking in music hall artists, though her father’s main occupation, having been a jockey in earlier life, was as an undertaker’s horse breaker. When Formby arrived at 8 Marsh Lane, only a five-minute walk from the Empire, he was met, to his surprise, by Eliza, sporting smudges and a moustache from black-leading the grate. She let him in, put him in the best room and made him a cup of tea. She told him, ‘You had better wait and see my father.’ George told her, ‘I like you. You look smashing. But I don’t like your black moustache!’ Wiping her face, she replied, ‘I like you too. But I don’t care much for your flat cap!’ George recalled, ‘That week I was on a “perhaps” two pounds which turned out to be ten shillings, with the result that Liza’s father took pity on me and gave me my Sunday’s dinner.’ He took the room and married Eliza a few months later in the local register office, on 11 August 1899. On the marriage certificate he gave his occupation as ‘actor’ and she was described as a dressmaker. George named Frank as his father, interestingly, and wrongly, referring to him as ‘Frank Booth’, cotton mill mechanic, deceased. Eliza must have known about this time that she was pregnant.

Marriage certificate of James Booth and Eliza Hoy, 1899

In their early married life the young couple lived with Eliza’s family at 8 Marsh Lane. Their first years together were marred by the deaths of their first three daughters as babies. Louisa, born in January 1900, died on 10 April, after suffering convulsions for three days. Edith Lily (or Lilian), born in March 1901, died on 4 August of the same year. According to the death certificate, she died of ‘zymotic enteritis’, inflammation of the small intestine caused by infection, after being ill for seven days. Eliza and baby Edith spent census night, 31 March 1901, far from home in the Infirmary at Chichester in Sussex. The explanation seems to be that Eliza had been staying with her uncle James and his family, as that was where her widowed mother Louisa was at the time. The third daughter, Beatrice Hoy, just one year old, died of diphtheria in early August 1903.

George had to supplement his irregular wages from the halls and ran a ‘small wares’ business. He was buying the rights to perform new songs at the same time. In 1898 he bought four from Fred Elton, who later wrote for Sir Harry Lauder. He also had a regular weekly engagement at the People’s Palace, St Helen’s. Such ‘turns’ paid only about 30s. a week, and George described to a journalist for The Sound Wave and Talking Machine Record in 1910 the atmosphere of singing rooms at the turn of the twentieth century. ‘The names of those engaged generally appear on the large mirror that usually adorns these places, written with the end of a wax candle.’ He said ‘he was never so proud in his life as when he saw his name appear in the premier position on the mirror of the public house where he got his first engagement’. It was at this time that he met Oswald Stoll, the vastly influential theatre manager, in Dublin. In 1898 Stoll had merged his business with that of Edward Moss and by 1905 there was an ‘Empire’ or ‘Coliseum’ theatre in most large towns.

I was singing at the Tivoli Music Hall (then known as the Lyceum) on my third engagement. I was giving the audience exactly the same repertoire that I did on the first, and you can imagine my surprise when I got a message that Mr Stoll wanted to see me. As all know, this gentleman is possibly the controlling force of the music hall world, and when he made me an offer of £5 a week I thought I was made. That was ten years ago…

This was the beginning of big money and fame for the ‘Wigan Nightingale’.

Many years later in an article in The Times about the painter L. S. Lowry, a northern industrial town of George’s time was described.

Mr Lowry’s skies may be unvaryingly grey and wintry, the streets and squares he represents may be lacking the least architectural distinction, and the open spaces muddy and squalid, but his colour schemes of black, brown and grey, lit with occasional touches of red, are pleasantly harmonious, and the small figures with which he crowds his scenes are skilfully grouped and full of life and of a gently melancholy humour. His is an art which seems equally descended from Breughel and from the elder George Formby.

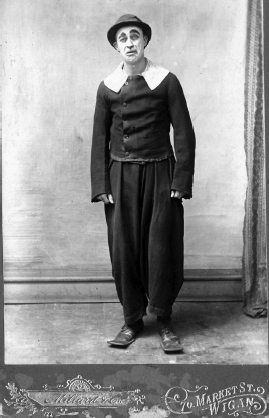

At this early stage in his career George’s stage persona was the living embodiment of Lowry’s matchstalk man, in shabby clothes, with pale face and gloomy expression and a hunched stance.

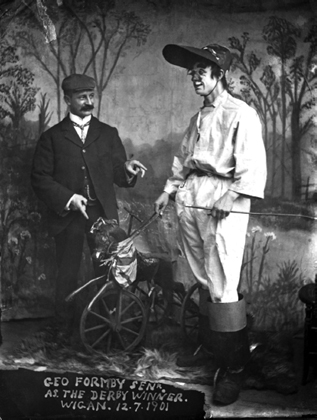

Formby senior in clown character

Early photographs show that his act also owed something to the traditions of the clown. In one taken in 1901 he is shown with heavily painted face and elaborate costume as ‘The Derby Winner’. Wearing heavy boots at the end of spindly legs, with pockets hanging out of his too-tight jacket and a hat jammed down on his head, he was gormlessness personified. He habitually powdered his eyebrows and painted two black spots on his forehead. This was helpful in playing to the gods (upper balcony) and apparently helped him rest his eyes by closing them for short periods, necessary because of the damaging glare of the limelight. Limelight was produced by the burning of hydrogen and oxygen in specially designed lamps. Some theatres had their own gas production plants, but in others the gas was taken in large gas bags carried on men’s backs. The hydrogen in particular was very unstable, especially in enclosed areas such as theatres, lit by candles or gas lamps and with cigarettes and pipes smoked freely in the auditorium. The lump of lime was in the focus of the gas and as the heat increased a very bright light was produced. The supply had constantly to be tweaked to keep the lamps bright. Heated limestone is an irritant to eyes and chest, damaging the eyes of George junior as well as those of his father.

The Derby Winner

Note the black spots on the forehead

Even before he appeared on stage George senior got a laugh from his audience. The orchestra would play him in, repeatedly, but he did not emerge. Eventually the music stopped and a voice called weakly from the wings ‘I’m ready!’ The laugh was gained, the music struck up again and he arrived. Standing alone on the stage, without a microphone of course, he would sing his songs, characteristically simple, some with tunes derived from Methodist hymns, and with catchy choruses. He would then move to the front and produce his ‘patter’, chatting in a gentle husky voice to the conductor and front-stalls audience as if conducting a private conversation. He would ask the conductor in confidential tones if ‘he had his men well under control, as there was a woman in the second verse’. Gracie Fields recollected that he ‘had her in stitches. In those days the theatres were deadly quiet – well, they had to be for him’. His ‘coughing better tonight’ was a regular part of the act. ‘I’ll cough you for five shillings and give you five coughs up,’ he challenged the audience. On other occasions he would praise his favourite patent medicine Zambuk, a herbal embrocation, and was the originator of the saying ‘It’s not the coughin’ that carries you off it’s the coffin they carry you off in’. All sorts of asides and comments amused the audience: ‘I might dance yet, but I might not’ or ‘they’re playing the chorus a second time, and I’ve not asked them to – very willing lads’.

Soon Eliza began to make George’s stage clothes and to stand in the wings while her husband performed. Once he lifted the drop cloth, revealing her legs and feet. ‘Aren’t I a lucky chap?’ he asked the audience. ‘These belong to me.’

She was, he said, his ‘Guardian Angel’, and at other times called her his ‘dear wife and pal’, adding, ‘She is worth her weight in gold and a million doctors. Only Eliza knows how to get me right.’ Over the years his act was refined and developed more and more, often with Eliza’s help and advice. She herself said, ‘Offstage, I did half the work for him.’ A central invention was the character John Willie, the archetypal Lancashire lad. It may be true that George was the first stage artist to exploit the use of dialect, and in the north this was massively popular. The song ‘John Willie, Come On!’ – words uttered by his wife when John Willie’s eyes strayed towards the ladies – produced a catchphrase, familiar to a wide audience, including those who had never seen a live performance by Formby. The slow delivery was deliberate, though his son Ted said many years later that as he drew his breath with difficulty he had to speak slowly. It was most likely George who coined the joke about ‘Wigan Pier’. The real Wigan Pier was a coal gantry on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. It was used to load coal from railway wagons into the canal barges below, about a mile from George’s home, but George spoke of it as if it were one of the fashionable pleasure piers at seaside resorts. ‘It’s aw right you lot laughin’. It’s very nice is Wigan Pier. Ah’ve been there many a time in my bathing costume and dived off t’ high board into t’ water.’ Not only George Orwell took ‘The Road to Wigan Pier’; many others flocked to enjoy the delights of the seaside and found instead a dirty industrial site.

George was ‘discovered’, as far as the London market was concerned, by E. H. (Ted) Granville in Leeds in 1902. Eliza remembered the circumstances of the introduction, through Belle Elmore, the wife, and in 1910 the murder victim, of Dr Crippen.

And Belle Elmore, who had come up from London, was impressed by George, she said, ‘You’re a good turn. You’re very good.’ (He wore slacks then, baggy slacks and big black shoes like Little Tich.) ‘I know two good agents in London and I will write to them to come up and see you. You are worthy of a Moss Empire Tour, you really are!’

‘Well, Miss Elmore,’ he said, ‘I’ll be delighted.’

So Ted Granville came down. He wore a beard.

Granville booked him to appear at the Royal Albert Music Hall, Canning Town, in October that year at a salary of £3 a week, and became his London agent. Formby was reluctant to try his luck in London, feeling that his act depended on the culture of northern humour and working-class life. However, with Eliza’s encouragement he gave it a try, his songs and routines portraying him as the naïve boy trying to fit in with the sophisticated south. The contrast between his northern accent and metropolitan bravado was humorous, and the more urbane and sophisticated his audience the more George exaggerated his provincial gormlessness. ‘Good evening, I’m Formby fra’ Wigan… I’ve not been in England long…’ Several of his most famous songs were written and performed for his London audiences – ‘Did You See the Crowd in Piccadilly’, for example, and ‘Looking for Mugs in the Strand’. In ‘Playing the Game in the West’ he boasted of what was supposed to be a great, but was obviously a dreadful, evening, ending with the lines:

And I’m not going home until quarter to ten,

Cos it’s My Night Out!

The title of one of his most famous songs curiously recalled his newspaper-selling past and foreshadowed a similar success for his son – ‘Standing at the Corner of the Street’. The sheet music reveals that Hunt and Formby wrote it, George sensibly, and increasingly, having a hand in his own material. Sometimes he combined the London songs with the Wigan material, opening at the Tivoli with ‘One of the Boys’ and ‘The Wigan Sprinter’. He also developed themes. A sequel to ‘Playing the Game in the West’ was ‘Playing the Game Out West’, exploiting a cowboy routine – another nonsensical notion considering his physical state. The great music hall star Marie Lloyd quickly became a fan and put in a good word for him, securing him a ten-week booking at the Tivoli, Oxford Circus.

On 26 May 1904 George Hoy Booth, George and Eliza’s first son and eldest surviving child, was born at home, 3 Westminster Street, Wigan, in a terraced house much like those in the familiar opening shots of the roofs of Coronation Street. At this point George senior still gave his occupation as ‘Small ware dealer (Master)’ on the boy’s birth certificate although he was playing the Argyle Theatre, Birkenhead, the evening the baby was born. Even this child’s arrival was blighted – he was blind. The often-repeated family story was that George was born with a caul, traditionally thought to be lucky. But this one apparently obstructed his eyes. As so often in the Formby stories, the facts are hard to establish and there are a number of versions of the extraordinary moment when the baby first gained his sight. It’s obvious that his mother was in the best possible position to know what happened, and Eliza’s account is intriguing.

He never opened his eyes when he was born, and although he didn’t open his eyes, he knew me. I used to feel his hand, and we had a dog called Nettle, she was a bitch and she loved Georgie and I made a little pram, like a cradle in the corner when I was doing my dressmaking. The little cot was next to the fireplace and I used to say: ‘Now, Nettle, when Georgie cries, you be very careful how you jump on that cot.’ And he knew it was a dog. He put his little hand out, and she would lick it. And she would take one jump into that cradle and she wouldn’t harm that child at all. It was quite high, but she would jump that high. Nettle – we had her from a puppy, and with her licking his hand he would be contented and would go to sleep with the dog lying at his feet at the bottom…

People said sea air would do his eyes good, so I thought I would go over to New Brighton one day and take him. Of course in those days you could [get a] two shillings return from Wigan to Liverpool on an excursion. So I went down, got off at Lime Street station and got the tram down to the pier head. When I got there, there was no boat in for New Brighton, but they said there’s one in for Hoylake – that’s a nice place. I said, ‘All right then, I’ll go to Hoylake’… I had made a cover that I put round my shoulders to take the weight off to hold him. I looked under the cover and stroked his face two or three times and all of a sudden as I was riding in the tram – he opened his eyes! That was the first time he had opened them from being born, he was three months old, and he smiled at me. I said, ‘Oh God bless you, Georgie – you can see!’ And I held his hand and I took him over on the boat… He had like a varicose vein on the top of his head when he was born, and he told me to be very careful, and just as he opened his eyes and I took him on the top of that boat, his little nose started to bleed. It was right on top of his head, where the opening is. Of course I was concerned, I was only young, but I wiped it off, it wasn’t long, and that disappeared and his eyes opened. And when we got to Hoylake, there was an old-fashioned iron bandstand, and the band was playing ‘Walker Walked Away’, one of my husband’s songs. Sent my husband a wire, ‘George opened his eyes – write home.’

In Australia in 1947 George described himself as being born blind ‘like a kitten’, not opening his eyes for three months, though in a Daily Mirror article in 1939 he had said that his wife had his caul and that it was likely to become a family heirloom. It seems impossible that it could cause blindness at all, and certainly not for any length of time. Importantly, Eliza, whose mother was a midwife, makes no mention of it.

Her account is very clear, but a diagnosis of the baby’s condition is difficult. She seems to think that the ‘varicose vein’ and the nosebleed were significant. Was George suffering from mild hydrocephalus, with pressure on the cranial nerve, which suddenly resolved itself? If so, why were his eyes closed?