CHAPTER EIGHT

I Could Make a Good Living at That

In the 1930s comedy was king, and British films often starred music hall stars. The censorship of films was very strict and themes of social and political realism were not allowed by the British Board of Censors, who listed forty-three banned items. So escapist comedy had a clear run. George’s second and last film for Blakeley was Off the Dole, described as ‘A Musical Merry Burlesque’ and released in July 1935. This time, as George later said, Blakeley ‘lashed out’ and spent £7,000 on making it. Arthur Mertz directed, George singing a song written by him, ‘I Promise To Be Home by Nine O’clock’, which his father had noted in his professional engagement diary in 1917!

The publicity blurb tried to widen the film’s appeal. ‘It is an established fact that periodically the whole English speaking world turns to the North of England for an exclusive brand of humour. At given intervals we become “Lancashire Conscious”, for there is in Lancashire humour that blend of simplicity, of wistfulness, of “mugdom” (to coin a word) scoring a triumph over sophistication, that is irresistible.’ Maybe. The film was wonderfully received in the north of England, with queues stretching all the way round the cinemas, but made little impact in the south. In the top hundred films in Bolton, Lancashire, in 1935 Off the Dole was number 27 – nationally it was number 566. It grossed £30,000 in seven weeks. The title, of course, would appeal to many in the audience who undoubtedly were on the dole at the time. Once again George played John Willie, struck off the dole for moonlighting and for his lack of interest in getting a proper job. Accused of hawking firewood on a handcart, John Willie replies, ‘That’s our furniture!’ Soon afterwards he becomes employed by his uncle’s detective agency to catch the ‘villains’ in a convoluted and flimsy plot interspersed with snatches of revue and touches of rather broad social comment. His character had more edge and cynicism than later roles would allow him though naivety was the overriding trait.

George and Beryl (Miss Seymour, in her last film role) sang two of the numbers together. The film included six songs – among them ‘If You Don’t Want the Goods Don’t Maul ’Em’ and ‘Isn’t Love a Very Funny Thing?’ as they were deemed to be such an important ingredient – but the most famous (or notorious) became ‘With My Little Ukulele in My Hand’. In 1933 Decca sent out test pressings of the song to reviewers. It was considered obscene, and Decca quickly withdrew it, re-recording it four months later under a new title ‘My Ukulele’. Twice little words caused problems: ‘playing with my uke’ was replaced by ‘playing on my uke’ and the baby boy, who originally had ‘a ukulele in his hand’, finally had ‘my ukulele’, softening the innuendo.

The offensive lines in the first version revolved around an encounter with a Welsh girl, Jane, sitting in the sand hills:

She said your love just turns me dizzy

Come along big boy get busy…

These were replaced in the second version with some awful cod Welsh:

I felt so shy and bashful sitting there

For the things she said I didn’t understand

She says ‘Your love just turns me cuckoo

Aye indeed to goodness look you’

But I kept my ukulele in my hand, oh baby…

Later, when the song was filmed in Off the Dole, all mention of Jane was omitted. Spencer Leigh notes that when in 1963 (the ‘Swinging Sixties’!) Joe Brown tried to broadcast the original song he was prevented from doing so not only on The Billy Cotton Band Show (because the BBC thought the lyric was too suggestive for a Sunday) but also on Thank Your Lucky Stars and Five O’Clock Club on ITV, presumably because of their early evening scheduling. It would not be the last time that George and the broadcasters were to clash.

A scene from No Limit. Jack Hobbs, the villain, driving a 1935 M.G. ‘P’-type and trying to stop George racing

Later in 1935 George made his first film for Basil Dean and Associated Talking Pictures, earning, at the outset, £30,000 per film. (£1,540,000) ‘Super slapstick was what counted in those days. So, before asking whether I could act Basil asked if I could swim, ride horses and motorcycles, and, if necessary, jump off a cliff. I said I could do all that with the possible exception of the cliff and he signed me up for my first movie, No Limit.’ George was presented as very much a Lancashire character and the script was co-written by Walter Greenwood, famous for his 1933 novel, Love on the Dole, which had been a great critical and commercial success. Himself born in Salford, of radical working-class parents, Greenwood was an ideal choice to write for northern audiences.

No Limit is highly rated by George’s critics. He himself considered it ‘the best bit of slapstick ever made’ and his personal favourite. Filmed in the Isle of Man, it was the perfect script for him, with his lifelong love of speed and motorbikes. One of the extras, Harold Rowell, described the ‘resourceful’ director, Monty Banks. Monty, an Italian with a pencil moustache and dark curly hair, was a distinctive figure at only five foot five inches tall. He ‘had obtained permission to take shots of the crowded grandstand. He ran up and down the road dressed in a canary coloured sweater, white plus fours, and black and white checked stockings… The crowd’s gaze followed him. They turned their heads like a Wimbledon crowd and in ten minutes he had obtained some wonderful scenes – all for a small donation to the hospital box’. Rowell was sitting with a couple of friends after a chaotic morning in which all the arrangements had gone wrong. Next to them was ‘a little bloke wearing an old-fashioned brown leather suit. We told him just what we thought about the lack of organisation and asked him who was the actor fool enough to take the star part in this lot. He quietly replied, “I am”’. Rowell thought George ‘a thorough gentleman. He was always considerate and like all really great entertainers he never spared himself. He gave of his best ALWAYS. If he had any failing I feel without the restraining hand of his wife Beryl he might have been far too generous and become the soft touch’.

George did most of his own riding on his bike, ‘an old AJS which I had built myself and called the Shuttleworth Special’. Rowell realised that George was a capable and enthusiastic motorcyclist and also that he was prevented from doing most of the stunts.

Although every precaution was taken to preserve George in one piece, I remember one particularly difficult piece of riding he did himself. Personally I consider it to have been the most dangerous of all the motorcycling scenes. It was planned to get pictures of him riding up the Cronk-y-Voddy straight, passing us, his rivals. In order to keep the camera focused on his face they fitted a solid tow bar to the back of the camera truck, and from this a short flexible section of about eighteen inches was attached to the steering head. You can imagine what would have happened if it had been pulled up taut… George rode under these conditions without turning a hair: in fact he seemed to enjoy himself.

George described another similar stunt. At a speed of over 70 mph (he claimed) he had to keep close behind the camera van, but to avoid bumping into it on corners. At the same time he had to keep his gaze on a white patch trailed from a rope from the van which marked the distance he had to maintain to stay in focus.

At the climax of the film, George, desperately trying to win the race, runs out of petrol and has to push the bike the last 500 yards. The scene was shot and reshot fifteen times. The last time, overcome by the heat and encased in heavy motorcycle leathers, George genuinely collapsed. Dean called it ‘perfect’ and it was the version used in the film, but a doctor had to be called for George. The filming was something of a nightmare for Beryl in two other respects as she ‘was scared stiff of bikes – she called them the tools of the devil – and never liked George riding them’. Nor did she like Florence Desmond, George’s co-star. The feeling was mutual. There had been a row because Desmond, mindful of her co-star billing, was angry that the Ealing Studios’ billboards on the side of their vans only mentioned George. She was apparently assured by Basil Dean that the matter would be rectified but nothing was done. She said later, ‘George Formby’s attitude did not help me to swallow my pride and let the matter rest, and so one day I got mad and told Monty Banks… that unless the boards were changed I would not go on with the picture… the offending objects were removed. George Formby was furious.’ Desmond was the last of George’s leading ladies to sing on film, in this case a solo number, ‘Riding Around on a Rainbow’. Beryl probably insisted after this that George should be the only singer in his films. In November George went to the Regal-Zonophone studios to record four songs, including, from the film, ‘Riding in the TT Races’. No Limit was an immediate box office hit on the national circuit. A permanent memorial to this most enduring of films – shown every year at the TT races – is the statue of George leaning on a lamp post at the corner of a street in Douglas, Isle of Man.

Harry Gifford and Fred E. Cliffe were the most prolific of George’s songwriters, responsible for about 90 of the 200 or so songs he recorded – ‘Fanlight Fanny’, ‘Our Sergeant Major’ and ‘Mr Wu’s a Window Cleaner Now’ among them. Fred Cliffe had, in the early years of the twentieth century, appeared on the music hall stage with Charlie Chaplin in Mumming Birds. Harry Gifford also had music hall roots, having collaborated with George’s father towards the end of his career on ‘Bertie the Bad Bolshevik’ in 1920. Their association began in 1932. George rarely met up with them in person and their relationship was dominated by his demands by letter for changes to the songs, but their partnership was a happy one, some letters including racing tips and one a request for their prayers before George played the dreaded Glasgow Empire! In July 1936 George found himself protesting to them that they would have to alter another lyric which would become a favourite.

Dear Lads,

Very many thanks for your song but I am very sorry to have to send it back to you as it is really too blue, you are getting too much on the sex stuff, try and clean it up a bit and send it along again, alas you will have to clean up ‘with me little stick of Blackpool rock’ for I cant [sic] work it in the state it is in, the Records have refused to do it as it is, so you had better get busy making them cleaner.

You couple of muckey buggers

All the best wishes

Yours Faithfully,

G F!

Earlier that year George began filming Keep Your Seats Please, which featured ‘When I’m Cleaning Windows’, though some lines of the original song, ‘The Window Cleaner’, were omitted.

Pyjamas lying side by side,

Ladies’ nighties I have spied,

I’ve often seen what goes inside

When I’m cleaning windows.

And the lines below from ‘Window Cleaner No. 2’, recorded only days after the film’s release, were also not included in the film version:

At eight o’clock a girl she wakes

At five past eight her bath she takes

At ten past eight my ladder breaks

When I’m cleaning windows.

Despite her determination never to work with the Formbys again, Florence Desmond was persuaded by Basil Dean to co-star. Her first reaction when he asked her, at lunch, was, ‘Cancel the cutlets, Basil. I won’t do it.’ The prospect of a generous salary, proper co-star billing and Dean’s vow to keep Beryl off the set must have sweetened the bitter pill, though nothing and no one could have carried out the last promise. Beryl was there, as large as life. Desmond was full of complaints. ‘I seemed to spend all my time running across the screen saying “But George”. When the cameras were not shooting over my shoulders I had to carry a child of three in my arms, and as the picture progressed she grew steadily heavier.’ Well, children do…

The summer and early autumn of 1936 were spent in Blackpool, George’s spiritual home, for a season in King Fun. Stan Evans for the South Bank Show remarked, ‘I think that George is like Blackpool… bright, breezy, free and easy, simple, full of life, full of enjoyment, and fish and chips – that sums George up – fish and chips, and his songs and his ukulele seem to go well with it.’ His energy is summed up in the bet he took to climb the 518-foot-high Blackpool Tower. Jack Taylor bet him £5 he couldn’t do it. George took him on and at the appointed time a crowd of 10,000 turned up to watch him. He was very enthusiastic to get started and only dissuaded when his film manager at Associated Talking Pictures, Ben Henry, threatened to sack him ‘if I dared set one foot on any part of Blackpool Tower except the lift’.

In October George gave a charity performance and a donation of £25 on behalf of Barnsley miners whose pit had been involved in a disaster two months before in which fifty-eight miners were killed. He was to attend a civic reception after going down into the pit itself and, later, distributed grocery vouchers to the bereaved families. George assured the reporter, ‘If ever there’s a man on this earth who deserves everything we can give him it’s the miner. I’ve lived among them and I know.’ It was this sort of comment that reinforced his working-class northern image. If he had lived ‘among them’ it was only in a general sense and not for long: the family had left terraced housing behind by the time George was six.

On the Blackpool sands

Ben Henry became involved in a lengthy correspondence with Fred Bailey. Fred, the son of a Wigan greengrocer who had once proposed to the widowed Eliza, was George’s close childhood friend from the Stockton Heath days and a keeper of the flame for him, recording everything he could of George’s career. He had gone with George to his first professional engagement at Earlestown, to encourage and support him. Fred’s father had made a considerable fortune and he and his wife Jessie had the resources to travel and to spend time away from the day-to-day running of the business. They went on holiday with the Formbys and helped them in innumerable ways – meeting them at the quayside after a cruise, for instance, and giving them a lift home. Fred attended the trade shows, arranged for members of the film industry and journalists before a film went on general release, and afterwards conducted informal research on the size of the audiences, the length of the queues and the sort of reception the films were getting. George liked to refer to his friends on stage and in songs. As part of his opening patter in the 1950s he asked ‘How are you doing, Fred?’ and in the song ‘The Old Cane-Bottom Chair’ one line speaks of ‘Jessie and the twins’.

On holiday in Jamaica. The central four figures are Fred and Jessie Bailey, George and Beryl

George and Beryl also sought the opinions of Fred and Jessie about songs. In a letter to them from the Queen’s Hotel, Birmingham, dated 9 March 1937 George wrote: ‘You are quite right it is entirely different to either of the other two I have done. I am glad to hear you like “Leaning by [sic] a Lamp post”. Yes I think it is a very nice song indeed. I have not recorded it and I don’t think I will as Regal Zonophone don’t care very much for it. They say it is not funny enough for me to record.’ Lacking his characteristic double entendres, it is one of the most charming and winning of all George’s songs, with a hint of melancholy that recalls his father’s style, and it’s extraordinary to think that it might not have been recorded. Beryl had as usual wanted to get George’s name associated with the composition, but the writer, Noel Gay, who had written the song originally for Me and My Girl, would have none of it. Apparently thwarted, Beryl was not done yet – she ensured that during his lifetime only George was legally entitled to perform it.

As the goose laying Associated Talking Pictures’ golden eggs, George had gained quite an influential position, which Beryl determined to use to her young brother-in-law’s advantage. Teddy, by now a teenager, was given a chance to work for Ben Henry. Beryl’s letter was full of bracing advice.

Dear Teddy

We sent off to you yesterday a dinner suit and some shoes, and now its all up to you to do your best, and very best, I had to do some talking to get you the job, so I don’t want you to let me down, I told Mr. Henry what a fine boy you were, and that you would do what you were told so now get busy – use your own brains – don’t listen to the twaddle of other people – keep a still tongue – don’t run other people down – always do the right thing and always say the people who you work for are the best thing that ever happened – for don’t forget they are the ones who are giving you your bread and butter.

Best of love from George and self and above all the very best of luck and health.

Yours Faithfully,

Beryl Formby

Keep Your Seats Please was released in March 1937, and by April Ben Henry was writing, ‘The picture is doing amazingly well wherever it is playing and it looks like establishing George in the front rank of screen comedians.’ Binkie Stuart (real name Alison Fraser), who was only three when she appeared with George in the film, recalled many years later that she had ‘great fun’ with the man she called Uncle George, when Beryl wasn’t around – but she usually was, standing right behind him. Binkie believed that Beryl was annoyed whenever the little girl stole a moment of the spotlight from George. She also remembered the volatile relationship between Florence Desmond and Monty Banks, George’s director again and (from 1940) the husband of Gracie Fields. Desmond wanted to have her breakfast on set, but when Banks refused she slapped his face. Binkie was hustled off quickly by her mother. She recalled, George ‘used to fluff his lines a lot and Monty would get quite exasperated with him. So did Florence Desmond. She could be quite catty and sometimes had no patience with him’.

Ted Formby as a young man

By this time George was making about three films a year so it was not long before the next one appeared. Feather Your Nest co-starred the beautiful Polly Ward, a niece of the music hall star Marie Lloyd who had admired George senior’s work so much. It was released in July 1937. In September Ben Henry was able to tell Fred Bailey that the film was selling very well and playing for two-week slots at theatres in Manchester. ‘Leaning on a Lamp Post’, recorded at last in September, became one of George’s best-known songs.

Shortly before the film was released George and Beryl had established the George Formby Club, annual subscription one shilling, whose object was declared to be ‘to aid deserving charities’. The first was the British Wireless for the Blind Fund. George’s poor eyesight, and his awareness that he had been born blind, gave him a special affinity with such charities. It was said that, ‘In his younger days there was a possibility of his losing his sight altogether,’ and the fear of this never left him. There was to be a monthly magazine with a letter from George and competitions with prizes. All this was arranged under the auspices of Associated Talking Pictures. Keep Fit, George’s next film, made in the spring and early summer of 1937, cashed in on the current rage, as signalled by its unimaginative title. This was the heyday of The Women’s League of Health and Beauty, whose members were distinctive in their short black satin pants and white shirts. George’s leading lady was Kay Walsh, who, it has been said, enjoyed a brief fling with George ‘during one of Beryl’s rare absences from the set’.

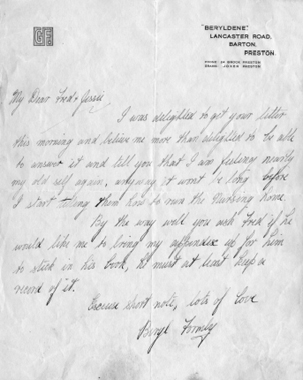

It’s true that during the making of the film, in June, Beryl was admitted to a private clinic where she had her appendix removed following a fall from a horse. She had been appearing with George at a gymkhana, on a horse sixteen hands high. In legging her up, the hand pushed her too hard and she fell clean over the horse. For a fortnight she was in pain, particularly when sitting, until it was decided she must have inpatient treatment. There was much speculation at the time in the hothouse of the film world, where gossip was always rife, that this was a cover for the real reason for her admittance – a hysterectomy. The story has often been repeated since by Beryl’s detractors. The argument ran that, fearing George would be tempted to dalliance with his beautiful co-star, to whom he was clearly attracted, Beryl had a hysterectomy to offer George ‘sex with no consequences’ so that he would not stray. This seems nonsensical. Why should Beryl, aware of his attraction to Kay Walsh, leave the film set where she had been keeping her customary guard on George’s virtue, if not for an emergency? If gossip is to be believed it led to the very fling she feared. In any case, after major surgery Beryl would presumably be unable to offer sex on any terms to anyone for some weeks, so such a stratagem would seem ‘not fit for purpose’. How extraordinary that anyone would think that she would have her own body mutilated and her sexual self compromised to stop her husband from ‘straying’, particularly if her absence catapulted her would-be adulterous husband straight into Walsh’s arms. Kay Walsh herself recalled that Beryl was taken off in an ambulance and that George ‘spent a busy night with ravishing film extras’. Not, one hopes, ravishing the film extras. But the most straightforward and obvious evidence about what was really going on comes from a letter to Fred and Jessie Bailey. Beryl wrote, with a nice touch of self-awareness, ‘I am feeling nearly my old self again, anyway it won’t be long before I start telling them how to run the Nursing Home… By the way will you ask Fred if he would like me to bring my appendix up for him to stick in his book, he must at least keep a record of it.’

Perhaps Beryl might be allowed the most sensible interpretation of her actions: that she was doing exactly as she said she was, though from her point of view the timing couldn’t have been worse. And the fling? It seems unlikely. Walsh had fallen in love with director David Lean the previous year and began living with him. One of Lean’s wives said of her that she was ‘terribly in love with him’. In her autobiography Kay wrote of the early days of their affair: ‘We worked all day and danced all night and slept through the weekend, waking late on Sunday to make love, to read the Sunday papers and to breakfast on eggs and bacon… We were asked everywhere – we were an attractive couple, we enjoyed life enormously.’

Beryl’s letter describing the removal of her appendix