CHAPTER NINE

Trailing Around in a Trailer

After Keep Fit was completed George opened at the Opera House, Blackpool, in the revue King Cheer, without Beryl, who was still convalescing. The show, with a cast of a hundred, was described as ‘easily the largest spectacular’ in the town, and ran for sixteen weeks. That summer of 1937 he bought Garthallen, Little Singleton, five miles from Blackpool, a five-bedroomed house with a tennis court, set in four acres of carefully landscaped garden. It immediately became Beryldene. Beryl told the George Formby Club that it was bought to cheer her up (or to appease her?), and they moved in on her birthday, 9 September. She also mentioned that the Preston house, though quite large enough for them, ‘wasn’t quite suitable’. It was semi-detached and apparently the neighbours hadn’t been too enamoured of George’s habit of turning the radio on at all hours of the night to listen to jazz. Meanwhile, George’s mother had not given up show business or promoting her children. In May she made a personal appearance at the Hippodrome, Aldershot, with ‘The Famous Formby Family: Frank – Louie – Ronnie’. Ethel was also performing separately, with a pianist. Eliza recalled:

I worked for twelve months as an act with my children, with Frank, with my eldest girl and her husband, and me. We did a four-handed act and Sir Oswald Stoll put the show on for us. A very well-dressed act and very nice. But it upset George – he didn’t like it… He felt very hurt because I had not told him they were going to put the show on, but I did it to help my other children. When you’re left with seven, you don’t know who to help or what to help, do you?

An artist’s portrait of Beryldene, Little Singleton

By this time almost the entire family was benefiting from the Formby name. Eliza said:

We worked for two years on and off – we worked in revues,

Moss Tour, Stoll Tour, and then Georgie came round and said,

‘What did you do it for, Mother?’

‘Well,’ I said, ‘to get a bit more money.’

‘Well,’ he said, ‘don’t bother, I’ll allow you something.’ Then he put me on an allowance. It was stopped the hour he died!

The year was crowned by George’s first royal command invitation. In November 1937 he performed before the king and queen at the London Palladium, alongside, amongst others, Gracie Fields, his friends Max Miller and Norman Evans, his former leading lady Florence Desmond and The Crazy Gang. The show was broadcast on the National Programme and described by the Radio Pictorial as ‘the radio high spot of the year’. George told the reporter he was nervous – ‘I’m not a bit ashamed to admit it’ – and that his appearance in the show would be ‘the greatest thing that has ever happened in my life’. The account continued, ‘If only his father were alive to see his son’s triumph. I’m too young to remember George Senior, but they still talk with reverence about his genius, of his battle with ill health… George Junior has a proud tradition to uphold and upholds it grandly.’

Playing in Dick Whittington in pantomime that winter, on the stage at the Newcastle Empire where his father had given his last ever performance, George was told that the show had broken the theatre’s box office record. He and Beryl marked the success by presenting to each of the twenty-five little girls of the chorus who appeared with them an inscribed silver bracelet as a memento. Gestures like this, gifts of flowers and chocolates, always of course organized by Beryl, were part of her management strategy.

Inside the studios he was hard working and cheerful except when rowing with his wife. There was no getting past Beryl when she had made up her mind. She was quick to make a fuss whenever she thought George was being put upon, such as when he was asked to play a scene he didn’t like or didn’t understand. Everyone was a bit scared of her.

So wrote Basil Dean in his autobiography, Mind’s Eye. Dean was one of many who thought George was tight-fisted. ‘One day George was seen to produce a ten shilling note at the refreshment counter to pay for a drink for one of the staff, a procedure so unusual that all movement ceased and all eyes were focused on the phenomenon.’ He did not think him a would-be womaniser though: ‘To do him justice I don’t think girls bothered him very much. But as a precaution Beryl was on the set at every take, keeping ceaseless watch.’

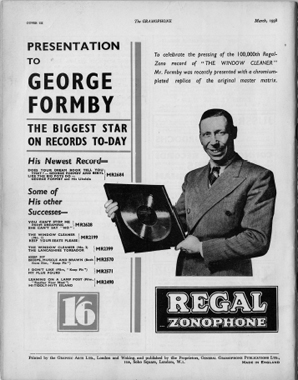

By this time there was a special Formby unit set up at Ealing Studios under the directorship of Anthony Kimmins, and films were to appear at frequent intervals. Work began on I See Ice in mid-October 1937, with Kay Walsh, to Beryl’s chagrin, once again providing the love interest. The theme reflected the craze for ice hockey at the time. The songs were ‘In My Little Snapshot Album’, ‘Noughts and Crosses’ and ‘Oh Mother What’ll I Do Now?’ In February 1938 George was thrilled to receive the matrix, or master disc, of ‘The Window Cleaner’, framed, as a gift from Regal-Zonophone to mark a hundred thousand pressings of the record. Beryl wrote a reply for him to Sir Louis Sterling. ‘It is something I shall value more than words can express… there is nobody more delighted than I am that the particular song has been such a success…’ At the end of the month, about a week after the trade show for I See Ice, Ben Henry commented to Fred Bailey, ‘I am inclined to agree with you that it is the best yet!’ Film Weekly summed it up well. ‘This is just the kind of hearty fooling that it is almost impossible to resist. It has plenty of rough edges, but it doesn’t give you time to think about them… George preserves his dogged optimism and gets across his essential human touch.’ The film went on general release in July. Back home again in Blackpool and replying to her friend, Hilda, who had, as ever, remembered her birthday, Beryl was more modest about it – ‘I think it is just as good as the others don’t you?’

George with the matrix of ‘The Window Cleaner’ With kind permission of EMI

In May George had topped the bill at the London Palladium for a week. This personal milestone passed, he bought his long-promised first Rolls, the symbol of his success. Thereafter he bought a new Rolls or Bentley every year until his death – twenty-six in total – always personalised GF 1 or GF 2. The Rolls-Royces were Beryl’s cars, and she was occasionally asked why the number plates were not her initials. George felt that those who asked hadn’t thought about it enough. BF?…

George even serviced his own Rolls-Royce

Two stylish and successful young people enjoying the fruits of success.

Note that the car had two spare wheels!

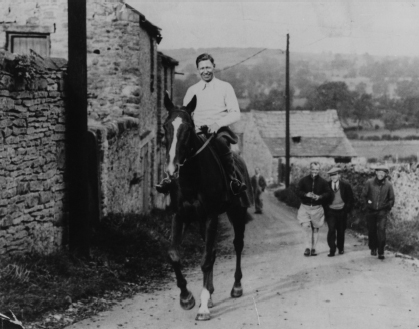

That year he had to miss his usual summer season at Blackpool as the film makers of It’s in the Air had to make the most of the fine weather for flying. Instead for one week he played Newcastle and was touched when a charabanc load of Blackpool fans came over the Pennines to see the show. While the Formbys were there they heard of 500 unemployed men from the North East who had saved up eight shillings each for a week’s camp in nearby Redcar. George and Beryl sent each man a large packet of cigarettes and in return received a model ashtray in the form of a horseshoe made by one of the men out of all the silver paper inserts from the cigarette packets, with a letter of thanks signed by all of them. George described it as ‘a gift which has always remained with us’. He revealed around this time that for him an ideal week’s holiday was to go up to Middleham or Beverley and live again the life of a stable lad. His love of horses and the open-air life, he said, gave him ‘complete relief of the mind’ from all the pressures of filming and the stage. He also recalled that it was the boxing matches at the stables which awakened his love of seeing fights, which he would go to Blackfriars to see if he found himself in London on a Sunday.

George found the outdoor life with horses relaxing and renewing

By 22 August It’s in the Air, described by Boy’s Cinema, a tuppenny weekly, as ‘a splendid British comedy thriller’, was finished. To coincide with its release early the following year the whole story was told in the magazine in excruciatingly small print, over ten pages, each of three columns. The film was hugely attractive for thousands of young men who would have loved to join the glamorous ‘boys in blue’. The Times reviewer, writing of it in January 1939 thought, ‘He may not be a smart guy… but he somehow gets along; he may not know his left from right, but he does know right from wrong… In its [the film’s] own unpretentious way it suits Mr. Formby’s unpretentious personality.’ His belief that George appealed to the maternal instinct of the female audience was spot on. From the first scene when George gave his gas mask to his engaging little dog Scruffy and was turned down for an Air Raid Warden’s uniform, his childlike disappointment set up the contrast between men of action and a character appealing to women. Many cinema-goers at the time considered this film his best, and the title song It’s in the Air became the number one RAF song of the Second World War. The sequence with George in a runaway aeroplane shouting ‘Mo-other!’ was one of the most popular moments in all his films. A sad footnote was that in June 1940 J. M. Wells, the airman who had actually done the wonderful crazy flying in It’s in the Air, was killed in action.

George’s popularity at this time can scarcely be overestimated. By 1938 there were nearly 5,000 cinemas in Britain and more were being built. In September he was booked to open the new £100,000 Avion Cinema in Aldridge, near Walsall. Huge queues formed hours before the 2.30 p.m. ceremony.

From the conversations in the auditorium it was quite clear what everyone had really come to see: what was far more important than the business of opening a cinema was the personal appearance of George Formby. His name was being spoken everywhere. People could be heard saying ‘Our George’ and ‘Good old George’, and the excitement was at the level which we now imagine was only achieved with the advent of the post-war pop star.

A short film programme was played before:

The much-awaited face peeped round the curtain and George Formby made his entrance. The crowd was ecstatic. His first task was to hand a cheque for twenty-five guineas from the Avion Directors… for the Walsall General Hospital Fund. He added a further cheque for £10 from himself and his wife. Loud cheering turned to a roar as someone produced a ukulele! George obliged with a song about his snapshot album and saucy pictures he had taken with a concealed camera. He managed to relieve himself of the ukulele and prepared to make his speech but a second instrument was produced as if from nowhere and he sang, ‘When I’m Cleaning Windows’… He then tried to leave the stage in order to depart via the auditorium. Everybody tried to press into the aisle to touch him, and to try and shake his hand. A crippled ex-serviceman who had hobbled nine miles to the cinema on his crutches managed to shake his hero’s hand. Afterwards he found that George had passed him a pound note! George Formby specialised in these tricks when meeting the public at events like this, and this added to the excitement felt by the crowd. After Mr and Mrs Formby had driven away the audience sat down to watch I See Ice…

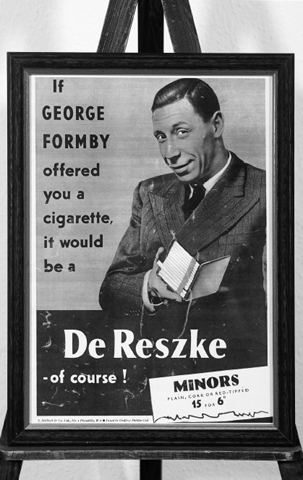

All sorts of ‘opportunities’ came George’s way in the late Thirties. He was pictured in An Album of Film Stars, produced by Player’s cigarettes, alongside Errol Flynn and Valerie Hobson and priced at a penny. Film Fun published a cartoon series, The Great George Formby, which ran into the early Fifties. Looking urbane and elegant, he advertised the stylish De Reszke cigarettes in the magazine Radio Pictorial. His radio career began in 1936 with an excerpt from King Fun, but was established in two series, A Lancashire Lad and A Formby Do. In October 1938 Beryl commented in writing to a fan that they ‘enjoyed making the Feen-a-mint programmes very much’. The makers of Feen-a-mint, a laxative, sponsored a series of radio shows which were broadcast on Radio Luxembourg. At about this time, George, weighing in at 10 st 3 lb, had been granted a licence to ride under Pony Turf Club Rules and took part in a hurdling race at Northolt Park. Unfortunately his horse, the odds-on favourite in a field of four, and ironically named Lucky Bert, refused at the last fence and he was disqualified. Perhaps a win was something of a long shot as George had only seen the horse for the first time that same day. Beryl said that it was ‘a great shame George didn’t win at Northolt as he had set his mind on winning with it being his first race after so long’. Not to mention the fact that it would have been his first win ever.

George’s career seemed to be going swimmingly when the risqué lyrics of one of his songs gave offence at the BBC and they effectively banned ‘When I’m Cleaning Windows’. At that time the Corporation saw itself as an active guardian of the nation’s morals and a range of songs and music were banned for a variety of reasons; they could be deemed too sentimental or unacceptable because they included references to drugs or prostitution. With George, whose songs offended the Dance Music Policy Committee more than once, it was a matter of ‘tastelessness’, ‘vulgarity’ or ‘smut’. On this occasion Dick Bentley, the compère of the feature You Asked for It …, a radio request show, wouldn’t play the record because ‘the windows aren’t yet clean enough’. George was furious.

An image of elegance and sophistication

It is a damaging thing to say about any artist and I am quite definitely taking legal advice on the matter. The song is always in great request and I have broadcast it dozens of times. Why, I sang it before the King and Queen at the Royal Variety Performance and I have sung it almost every Sunday at charity performances sponsored by hospitals, churches and other organisations. Recently I went to a hospital to sing to sick children from about five to fifteen years of age… Afterwards I was told that the nurses played it on the piano and all the kiddies sang it in chorus. Even the matron approved.

A formidable ally indeed, but it was the reference to the Royal Family that was the clincher. With them lined up alongside the rest of the nation, the BBC was completely out in the cold.

On the following Saturday George appeared in Sing Song. Before the programme began the announcer said: ‘As an extra attraction we present George Formby, to whom we owe an apology. An unfortunate reference was made to one of Mr Formby’s songs in a programme last Monday. We are sorry this occurred but we are still the best of friends, which is borne out by the fact that George is with us tonight.’ The apology was given at peak time, just before the nine o’clock news. But George and the BBC managers were simply not going to see eye to eye. The manager of the North Region wrote in 1942, ‘The man is essentially vulgar and he seems to be incapable of producing anything that is not objectionable.’ Not only was he apparently keen to censor the biggest star in northern England, but he somewhat overstated his case. No one (except him), then or now, has found ‘Leaning on a Lamp Post’ to be ‘objectionable’.

The pantomime season found George at the Palace Theatre, Manchester, in Dick Whittington, but he fell ill halfway through. A letter dated 23 January 1939 to Beryl at the Midland Hotel, Manchester, reads, ‘I am very sorry indeed to hear this afternoon that George is ill and has had to come out of the show. Mr Carne is away from the office so that I am writing to you to say how sorry we are to hear of George’s illness, and very much hope that it is nothing serious.’ It was serious enough to result in a five-week cruise to the West Indies, George’s first major break since 1934.

In early 1939 the Sunday Express began ‘George’s Laughter Page’ to ‘make your sides shake even if Hitler makes your head ache’. Full of corny gags and ‘Songs I Should Never Have Written’ not to mention tips such as ‘How to knit a Gas-mask for your canary’, the humour was of the mildest, but the feature was an explicit attempt to make people ‘forget their worries and troubles’ on the eve of war. George’s role was cut out for him.

George’s next film was Trouble Brewing. In the five weeks it took to make, his co-star, nineteen-year-old Googie Withers, recounted that he never said one word to her. One day something went wrong in the middle of a scene and they were told to keep their places until it was fixed. ‘There he was, alone with me for the first time and not being watched by Beryl, and he said out of the corner of his mouth, “I’m sorry, love, but you know, I’m not allowed to speak to you.” It was very sweet.’ She thought Beryl a ‘funny woman. I don’t know why she was like that. I don’t think any one of us young girls wanted to get off with George’. But famously he took his chance for a passionate kiss in the vat of ‘beer’ at the end of the film. ‘He quite inadvertently put his hand on my knee and suddenly felt a girl’s thigh… and then he kept it there and he started to visibly sort of shake… and then we had the kiss, and my goodness it was quite a kiss that he gave me! But then Beryl was in on it like a flash. She said “Cut!” after it had lasted about three seconds. I remember Kay Walsh said to me that she had to run along a street and then they both fell down on the ground, I think, and then they had their kiss, and she [Beryl] did the same thing: she ran along with them, fell on the ground with them – out of shot of course – and said, “Cut!”’

It has been said that one reason Beryl did not like George playing romantic scenes was that they were unpopular with children in the audience, who found them soppy. A young fan confirmed that: ‘Any suggestion of romance was greeted with inattentive chatter and the ultimate sin of a screen kiss earned itself a chorus of raspberries.’ Both George and Beryl were keenly aware of the importance of the youngsters who were fans. Cinegram even suggested that George had censored some of the charlady’s lines in the film as being unsuitable for children.

Ben Henry was honest enough to write, ‘A tremendous number of people think this picture is better than It’s in the Air, but this is not my opinion.’ It wasn’t the opinion of The Times reviewer either. ‘The early sequences are laboured and rather humourless but the film gradually warms to a most amusing climax.’ Nevertheless he gave an insight into George’s appeal: ‘It is a tradition among clowns that they must always seem more stupid than ourselves; just a little more muddle-headed, a little more clumsy and a little more destructive than we could ever be and thus we delight in their antics with a warming feeling of superiority. Yet the clown must be well-intentioned; he must have a good heart and he must triumph in the end. Mr George Formby is such a clown.’

George habitually looked at the rushes of his films from near the front because he was short-sighted. He and Beryl always sat with an empty seat between them. Everyone else sat at the back, which made it look not only as if he and Beryl had no friends, but that they were not on speaking terms. But they always sat that way since the early Ealing days – George, then his distinctive light grey trilby hat, familiar from so many of his films, next to him in its own seat – then Beryl. The hat was developing a life of its own. It even had its own chair in the corner of the studio restaurant. By this time it was much the worse for wear. Bought in Manchester for ten shillings, it had been worn first in No Limit and in seven films subsequently. Though carefully cleaned after each film and stored in a special steel hat box, its career of absorbing custard pies and studio snow had nevertheless taken its toll. The hat band had come away, the crown was wearing thin and there was a hole in the brim where it had been nailed to a wall. But George swore to wear it until it fell to pieces on his head.

Come On George posed the problem of moving a racing stable to Ealing Studios. Six horses were brought in from Mr Younghusband’s stables, and the star of the show was the obedient Diana, ridden by George in many of the scenes. Despite George’s background as a jockey the studio insisted on insuring him for £60,000. Pat Kirkwood, aged eighteen at the time, was his female lead, and her relationship with George was famously difficult. As a singer of some reputation she expected the opportunity for a solo. In fact she was not allowed to sing at all. Beryl insisted that her long hair be cut and her clothes be of the plainest. Kirkwood couldn’t understand why George ignored her. ‘There was no communication from [him] – not even a cup of tea or a “good morning”.’ The director Anthony Kimmins eventually told her that George had probably been warned off by Beryl ‘who was apparently very jealous of George and still madly in love with him. I felt rather sorry for her in spite of her making me look like a scarecrow, because she must have suffered a lot of pain’. To achieve the final close-up kiss Beryl was lured from the set by a ‘telephone call’. Kirkwood recalled, ‘All was ready to go, and I was instructed by Tony to: “Grab him and let him have it and don’t break till I say cut.” As I was so utterly fed up with all these capers, together with losing my locks, looks, and entire persona, I decided to do just that.’