I

If personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures, then there was something gorgeous about him, some heightened sensitivity to the promises of life, as if he were related to one of those intricate machines that registers earthquakes ten thousand miles away. The responsiveness had nothing to do with that flabby impressionability which is dignified under the name of the “creative temperament”—it was an extraordinary gift for hope, a romantic readiness such as I have never found in any other person and which it is not likely I shall ever find again.

—F. SCOTT FITZGERALD, The Great Gatsby

1

SEPTEMBER 2, 1965

How ironic that the funeral of the man who had purified architecture and erased history from building facades should take place at the Cour Carrée du Louvre. Le Corbusier had constructed brazen forms of rough concrete in lieu of the fluted columns and ornate medallions that now surrounded his casket, draped with the French flag. He prized boulders and beach pebbles, not pomp.

But the setting fit. Le Corbusier had always sought entry to the palace, even when its ruler was a despot. He had worked with many of the most powerful leaders of the twentieth century, regardless of their values or politics, so long as he might build their monuments. He mocked them, but craved their complicity—provided that they served his purpose. He would have scoffed at the spectacle with which a society that had often attacked him and thwarted his dreams now bade him a lavish public farewell, but it fulfilled his ambitions.

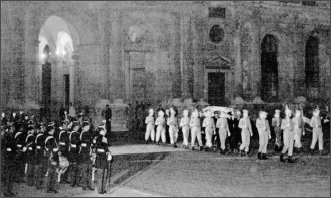

The ceremony was high theatre. The weather helped make it so. A strong wind was buffeting fluffy cumulus clouds that late-summer evening. Their rapid flight beyond the roof balustrades and pediments was illuminated by powerful beams from two light projectors below. More than three thousand people braved the unseasonable cold as they waited for the arrival of Le Corbusier’s remains. Then, at 7:40 p.m., all heads turned. Carried on the shoulders of a retinue of undertakers, the coffin slowly penetrated the crowd. A detachment of twenty young soldiers, “in bright-colored uniforms bearing torches, surrounded it.” To the lugubrious beat of Beethoven’s Funeral March, the convoy passed “in front of the four squadrons of the Republican Guard presenting arms.” As the clouds began to give way to a clear and starry sky, the coffin was placed on trestles “at the top of a huge inclined plane” covered with grass. “In the rear, six guards in full-dress uniform with drawn swords were silhouetted against a background of columns.”1 A couple of minutes later, the wind lifted the covering off the casket, but no act of nature could deflect the order and majesty of the precisely orchestrated proceedings. Often accused of wanting to destroy Paris, Le Corbusier was now being honored with the ultimate symbols of the tradition he had threatened.

THE BUILDING WITH which Le Corbusier had liberated the idea of home—much as Coco Chanel had freed women by letting them wear pants—contained, on a modest scale, a space similar to this vast paved garden within the Louvre. His 1929 Villa Savoye also encased raw nature within man-made walls. Its forms were clear and spartan in contrast to all this Baroque excess, but it, too, showed the wish to worship, and to tame, the elements of the universe. Like the architects who at the bidding of Henri II, Richelieu, Louis XIV, and Napoleon had made the Cour Carrée, Le Corbusier had framed the sky and exercised quiet control over the outdoors, rather than submit to them. The result was a staged ambience that steadies the breath.

Military honor guard at Le Corbusier’s funeral service in the Cour Carrée du Louvre, September 2, 1965

Le Corbusier knew that well-placed walls could alter our mental states, that through measure and proportion one might bring calm to the human soul. The style of the Villa Savoye was as restrained as the Louvre was lavish, but a consciousness of visual effects was everywhere. Human beings must cultivate their environment to the fullest extent possible.

IN THIS COURTYARD where the kings of France had once strolled with minions vying for their attention, the assembled coterie now consisted mainly of government officials, young architects, and Le Corbusier’s work associates. There were few relatives or friends among the hordes who had just returned to Paris from their summer vacations.

Le Corbusier, too, had been on holiday. Four days earlier, his body had been spotted floating about fifty meters from the shore at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin on the Côte d’Azur. Since the tenth of August, he had been staying alone in his small, square cabanon, nestled into a rocky slope overlooking the Mediterranean. Accessible only by a foot path, the cabanon was surrounded by a panoply of cacti, lilacs, honeysuckles, and lemon and orange trees. The only sounds were the constant lapping of the Mediterranean surf on the shore below and the rumbling of the occasional local train on the tracks just behind the uphill wall. The rugged simplicity of the one-room house was strident next to the neighbors’ Italianate villas and the high style of Monte Carlo, within walking distance along the coast.

Sheathed in rough pine logs, this modest dwelling was like the Alpine mountain huts of Le Corbusier’s childhood. The bare-bones furniture comprised a single table, a couple of simple wooden stools, and the bunk bed that had been his wife’s. Before her death seven years earlier, Le Corbusier had slept on the floor; since then, his mattress was where hers had been. There was a small, train-style industrial sink near the table. The conspicuous toilet—separated from the headboard of the bunk bed by only a flimsy curtain—testified to Le Corbusier’s belief that a water closet was the most beautiful thing in the world.

The sparse and minimal cabanon had its aesthetic distinction. Its measurements of 3.66 by 3.66 meters, and 2.26 meters for the height, were inspired by his “Modulor” device, the invention with which he made human scale the determining factor of his architecture. The multipurposed table, constructed from handsomely grained blocks of olive wood, was angled under the one picture window so that the plane of its top penetrated the tiny space with a strong beat. Le Corbusier had painted vibrant, sexy murals on the wooden window shutters and the entrance wall. These erotic celebrations counteracted the austerity of the rest. The hardworking man who rose at six every morning to do his gymnastics and start his day’s work loved physical pleasure unabashedly.

AMONG THE FEW PEOPLE who had seen the architect since he had arrived in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin were the Rebutato family, the proprietors of the small restaurant that abutted the cabanon. Their lives were entwined with his. The Rebutatos’ “police dog” was waiting for Le Corbusier on the corrugated iron roof of the cabanon during his final swim and was falsely assumed to be the architect’s own pet when its photo appeared in the Parisian newspapers in the following days.

For three weeks, the Rebutatos had delivered Le Corbusier the meals he ate in solitude. They were concerned about his condition. But when the local doctor visited two days before Le Corbusier died, he assured them that, while the architect was far from strong, there was no need for alarm.

Robert Rebutato, the son of the restaurateurs, was an architect in Le Corbusier’s Paris studio. For many summers, he had been Le Corbusier’s constant companion for the vacation routine of two swims a day, one at the end of the morning, the next in the late afternoon, each followed by an aperitif. Over ritual drinks, Le Corbusier would hold forth to his acolyte about architecture, nature, color, or whatever the passionate theme of the day was.

Robert had been troubled by a conversation with Le Corbusier the day after the doctor’s visit, when the junior architect was about to head off to Venice, to work on the hospital Le Corbusier was designing there. Le Corbusier asked his young friend to take a manuscript edited by Jean Petit—a publisher and loyal devotee of the master—for the book Corbusier Himself.2 Le Corbusier had marked his self-propagandizing text with corrections and changes and asked Robert to give it to the editor in Paris. Robert said that since Le Corbusier would be returning to Paris himself at the start of September, he would most likely get there before Robert arrived from Venice. For Le Corbusier to hand over such an important document was completely out of character; he always dealt with such things on his own.

But Le Corbusier insisted. Reluctantly, Robert took the envelope. It made him uneasy: “It shocked me. I found it bizarre,” he said later.3

Robert recognized that the world-renowned architect who liked to present himself as a straight shooter, resolute in his convictions, with a bawdy, friendly wife, had his mysterious sides. But like most everyone else, Robert had no idea of the extent to which Le Corbusier was morbid and plagued by demons. The celebrant of life who exalted nature in his sun-infused murals and tapestries often experienced moments of crushing darkness.

THE FOLLOWING DAY, Simon Ozieblo and Jean Deschamps, two fellow vacationers, found Le Corbusier floating dead near the shore. His head was turned “toward the bottom.” They brought his body onto the beach at about 10:00 on that sunny August morning.

Roughly an hour earlier, Ozieblo and Deschamps had seen him swimming with great difficulty. “Each time he returned to the edge, he experienced the greatest difficulty climbing the boulders separating him from the path along the creek,” they said.4 But when they had offered to help him, which they did a number of times, he had refused with a smile.

For much of Le Corbusier’s life, swimming had been his way of bringing himself to his preferred mental state. Almost forty years earlier, when he was anxiously awaiting the results of the competition for the Palais des Nations in Geneva and was feeling highly impatient toward his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, with whom he was collaborating, he had vigorously stroked his way toward equilibrium. From the small house he had built for his parents in Vevey on the shore of Lac Leman, Le Corbusier wrote to his “little Vonvon”—Yvonne Gallis, the Monegasque woman whom he was to marry three years later—“If I hadn’t had the chance to get into the water (and I swim amazingly well) I would have been completely disgusted.”5 Having grown up landlocked and taught himself to swim in his twenties, he had discovered that moving weightlessly through water under the open sky was his salvation.

Entering the sea at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, August 1965

Ozieblo tried mouth-to-mouth resuscitation for three quarters of an hour. “There was still a pulse, the heartbeats were irregular, but I already knew that death would do its work: a thread of blood was running down from the victim’s mouth,” he said.6 He and Deschamps learned the identity of the old swimmer only after the local firemen arrived. For another half hour, the firemen continued to attempt artificial respiration with oxygen and “shots of solucamphire,” but to no avail. In the previous months, Le Corbusier had been rereading his well-worn, marked-up copy of Don Quixote, a favorite book of his youth.7 He had bound it with a piece of coarse-haired hide from a beloved dog. Now, like Cervantes’s hero, he seemed to have picked the time, and way, to die.

LE CORBUSIER’S LIFELONG task had been to exercise control, corral his emotions, determine the appearance of buildings, and promulgate his gospel. Death was an inalienable part of nature; so as not to fail in relationship to it, one must work with it intelligently. In a private letter to his mother in January 1927, a year after his father’s death, he referred to “the injection he had been given which allowed him to leave this earth without being buried in it. Hour by hour, I kept seeing dear papa in his bed: sunset. His beloved voice, his last words.”8 It was euthanasia with poetry.

Le Corbusier once asked his Parisian doctor, Jacques Hindermeyer, his closest confidant late in life, what he would do if he was an architect. The doctor replied that he would build houses upside down. Le Corbusier was puzzled. “What do you mean?” he asked.

Hindermeyer explained, “Since you celebrate sun, space, and greenery, I would build them like pyramids to let the most in.”

“That’s not bad,” Le Corbusier said, approving with a smile. He then answered Hindermeyer’s inquiry as to what he would do as a doctor. “I wouldn’t do anything. I would just let people die peacefully.”9

Death, like architecture, is ideally in accord with the inescapable cycles of the universe and should have grace and proportion. Like the terraces and roof gardens of Le Corbusier’s houses, one’s way of dying should provide a direct connection to the cosmos. “How nice it would be to die swimming toward the sun,” Le Corbusier had been quoted as saying on two different occasions.10

DR. HINDERMEYER had last seen Le Corbusier at the end of July, at lunch in the doctor’s sprawling apartment on the boulevard Saint-Germain. For years, they had maintained the habit of dining together shortly before embarking on their summer holidays. With their strong and trim physiques, neat haircuts, and immaculate suits, the two dignified professionals could readily have been taken for a father and son in business together, perhaps industrialists or merchants.

Hindermeyer felt that Le Corbusier looked fatigued, which he attributed to the architect having worked especially hard of late. But he was surprised when, after having been summoned from the table for a phone call, he returned to the dining room to find his guest standing up, with his shirt off. He asked what was going on. “I don’t feel well, it’s as if there were rats in the plumbing,” said Le Corbusier.11

The rough terminology from the building trade amused the doctor, but its message concerned him. He quickly retrieved his stethoscope and was distressed to discover Le Corbusier’s “heart in complete arrhythmia.” But there was no getting him to abandon his plan to leave for Roquebrune-Cap-Martin the next day. When Hindermeyer warned Le Corbusier of the severity of his health situation, his patient and friend answered—in his usual way of looking at himself as if he were his own astute observer—“You know me well, and you know that I don’t want to suffer physical diminution. Imagine the scene: Le Corbusier in the wheelchair and you pushing. No, not that, never.”12

But then Le Corbusier quickly added, “I’m not ready to go, I still have so much to do.”13

Hindermeyer phoned Le Corbusier’s cardiologist and arranged for his patient to be seen that afternoon. In the evening, Hindermeyer went to Le Corbusier’s apartment. The setting was a different world from the doctor’s own flat, with its paneled walls and mélange of family antiques evoking previous centuries in a grand Haussmannian building in the elegant faubourg St. Germain. In Le Corbusier’s stark, if spacious, digs on the outskirts of the sixteenth arrondissement, there was no molding; the furniture was streamlined; and industrial windows looked over modern Paris and the new suburbs beyond the city limits. The two-story nest had changed little since Le Corbusier had designed it, at the top of a boxlike apartment building of his own making, more than thirty years earlier.

Le Corbusier was lying on his high-legged, platform-style bed, which was positioned near the open cylindrical shower. The doctor made some recommendations for the holiday. Unable to persuade Le Corbusier to give up swimming completely, Hindermeyer insisted that the septuagenarian not dive into the Mediterranean too early in the day. Le Corbusier consented to the doctor’s further advice that he not swim too hard and confine himself to one swim a day, at noon.

Toward the end of August, Hindermeyer was pleased to learn from the Rebutatos—such loyal, devoted guardians and protectors—that they were giving Le Corbusier all of the requisite pills and injections and that the architect was taking only short swims. But on August 25, the day before he was to return to Paris, Le Corbusier disobeyed all the advice. He had plunged in shortly after 8:00 a.m. By the time Ozieblo and Deschamps saw him, he had been swimming for nearly an hour.

AS WORD OF Le Corbusier’s death spread all over the world, it was said only that he had drowned—startling enough for a man of his age. But the doctor whose advice Le Corbusier had deliberately spurned, and the young colleague to whom the architect had implied he would not return to Paris, could not help wondering if it was an elegantly orchestrated suicide.

2

The setting of Le Corbusier’s funeral had its irony; so did the presence of all those people. He had devoted his life to trying to build spaces to accommodate the physical and emotional requirements he considered inherent in all human beings, especially the poorer masses, but he disdained “bourgeois” taste and would have distrusted many of the individuals who came to pay him their last respects, for he knew that they did not really grasp or advocate what mattered to him.

Few among the shivering crowd felt any intimacy with the man they had come to honor. Most deplored his wish to raze large parts of existing cities, to eradicate the old and replace it with startling new vertical communities, and they were relieved that so few of his concepts had become reality. But most everyone recognized his relentless devotion to his beliefs. He was convinced that the buildings we inhabit in our private lives, and those where we pray and learn and run our governments, are key determinants to the thoughts and emotions that occur within them. By re-forming our physical surroundings, he had tried to alter our existence irrevocably. Even if people debated the success of his buildings, no one doubted that he had permanently changed the visible world.

To the public, however, Le Corbusier’s personality and ways were elusive. He offered no images of café life with glamorous friends. The man himself seemed more remote than Sartre, Picasso, Freud, and other great pioneers of change in the twentieth century—although he, too, had initiated a radical alteration of thought and was recognized for his impact on civilization.

Even his name had violated custom and shown the triumph of imagination. At age thirty-three, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had transformed himself from an ordinary person into an institution. His sobriquet echoed the “Le C.” of “Le Christus”—“Jesus Christ” in French. Additionally, with its sequence of syllables like four right angles making a square, “Corbusier” had a built, structured ring to it. It resembled a bare-bones building free of ornament and clear in structure. The “Le,” further, objectified it. Especially in its shortened form, “Corbu,” the name was also kin to “corbeau”—the French word for raven, the powerful bird of death. Like another twentieth-century linguistic invention, “Bauhaus,” it had come to symbolize modernism, in all its effrontery as well as its brave elegance. It was no surprise that Le Corbusier was the first artist ever to be honored by these obsequies before a vast audience at the Cour Carrée of the Louvre, previously reserved, on the rarest occasions, for military or government leaders.

The Parisian newspapers called him, unequivocally, “the greatest architect in the world.” He had “achieved control of the sun.”14 Even though “in 1925 he wanted to raze half of Paris,”15 he “has liberated us from a tyrannical past.”16

For three days following his death, Le Corbusier’s body had been lying in state in the town hall of Menton, near where it had been swept ashore. Then, on a route prepared by the police forces, it went to the monastery the architect had built near Lyon, at La Tourette, where it was displayed ceremonially throughout the night of August 31. During the afternoon prior to the ceremony at the Louvre on September 1, the casket had been in Le Corbusier’s office on the rue de Sèvres, for more intimate viewing by his friends and colleagues. It was all part of “the carnival” the architect had predicted. Referring to the way, when he built his great Unité d’Habitation in the early fifties, he was labeled with the term that in Provençale dialect means “inhabited by a fairy,” implying that he was a madman, he told Jacques Hindermeyer, “My whole life, they made fun of me and criticized me. They called Marseille ‘La Maison de Fada.’ You wait: after my death, they’ll use me for themselves. I’ll become a great man. That’s why I am telling you not to go to my funeral. It will be a masquerade.”17 In an autobiographical essay, Put into Focus, completed shortly before his death, he said that the speakers would be more interested in themselves than in the one who died.18 Someone as privy as Hindermeyer to the truths of human behavior should not have to suffer such hypocrisy.

Two weeks before he died, Le Corbusier saw a man smashing against a rock an octopus he had just harpooned. The architect compared himself to the sea creature. “For most of my life, I have simply been smashed down. Many people were so jealous, they wanted to destroy me, to crush my head just like that octopus.”19 He never tired of finding analogies to vivify his tortured martyrdom. “They grilled me over a slow fire: grotesque!!” he cried after one failed collaboration.20 In 1953, at the ceremony in London where he was presented with the Royal Gold Medal recommended by the Royal Institute of British Architects and approved by the queen—an occasion when one glowing tribute followed another—he chose, rather than to bask in the pleasure, to declare, “If tonight I am wearing this magnificent medal, it is because I was a cab-horse for more than forty years…. I received, like a true cab-horse, many blows with a whip.”21 He was, chronically, the victim of merciless critics and bureaucratic corruption; as a result, he had not built a fraction of what he hoped to build. Nor had he been credited adequately for whatever little he had done. Unlike Don Quixote, he had never had illusions to the contrary, but, like Cervantes’s knight, he had awoken to the hard truth of a lifetime of being pummeled.

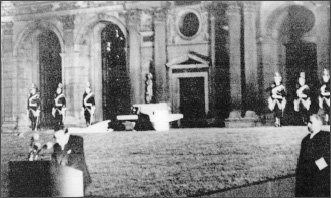

Now, in the Cour Carrée of the Louvre, he was only a hero. Following Beethoven’s solemn dirge and the impeccable staging of the entrances and the exits of the uniformed honor guard, the casket made its journey forward on that rolling sea of shoulders with magisterial choreography. In addition to the crowd packed into the vast courtyard, hundreds of thousands of Parisians, tuned in to the ceremony on their radios or televisions, heard the single, memorable eulogy that followed. The enthralling speaker with his deep, tremulous voice was Charles de Gaulle’s minister of culture, André Malraux.

Malraux had been a champion of Le Corbusier’s work and had recently commissioned the architect to design a major new museum of modern art on the outskirts of Paris, although Le Corbusier had rejected the site. Other people in power had disdained Le Corbusier’s modernism or faulted his politics. Some had declared him pro-Soviet; others thought him fascist. There were rumblings that he had collaborated with Vichy. But Malraux was one of the few people who considered Le Corbusier’s genius more important than anything else about him, and he had been consistently loyal.

Le Corbusier’s casket entering the Cour Carrée du Louvre, September 2, 1965

At precisely 10:00 p.m., Malraux faced the clustered microphones. Ambassadors stood at attention, and young architects fought back tears. The broad-shouldered culture minister stood with one foot slightly twisted as he leaned on the lectern, stared downward through his black-framed glasses, and began his homily. His straight, dark hair was swept back; a white pocket handkerchief provided the only relief against his somber double-breasted suit. With gravelly timbre and priestlike cadences that imparted portent to each word, Malraux announced that a Greek delegate would deposit a portion of earth from the Acropolis on Le Corbusier’s grave and that a representative from India would pour water from the Ganges over the architect’s remains in honor of his creation of the territorial capital of Chandigarh.

Then this most intellectual of public figures shifted tone. Malraux had no intention of letting people forget the ignominy suffered by creative geniuses. “Le Corbusier has had great rivals, several of whom still honor us with their presence; the others are dead. But no one else has so forcefully signified the architectural revolution, for no one else has been so long and so patiently insulted. It is through disparagement that his glory has attained its ultimate luster.” Malraux touched on Le Corbusier’s achievements in painting, sculpture, and poetry. Those were the calmer realms. Le Corbusier’s battles were confined to issues of building and to urban design. “Only for architecture has he done combat—with a vehemence he has shown for nothing else, since only architecture awakened his impassioned hope for what might be achieved for mankind.”22 Le Corbusier had to stay the course like a solitary crusader and had encountered infinitely more obstacles than accolades, yet his accomplishments were such that now the minister could proudly read tributes from the presidents of the United States and Brazil, from the esteemed architects Alvar Aalto and Richard Neutra, from colleagues in the Soviet Union.

André Malraux giving his homily at Le Corbusier’s funeral service

Le Corbusier and André Malraux laying the cornerstone for the Assembly Building in Chandigarh in 1952

There was one moment above all when Malraux homed in on the real work of the controversial pioneer whose body rested at his side. This was when, early in his eulogy, he quoted Le Corbusier’s own declaration of his lifelong goals: “I have worked for what mankind needs most today: silence and peace.”23

LE CORBUSIER’S warnings of false theatricality, however, were more warranted than anyone in the funeral audience could have imagined.

The day before the ceremony, Malraux had telephoned a demand to the Indian ambassador to France, Rajeshwar Dayal: “You have to come with some water from the Ganges.” Dayal had replied that he didn’t have any, to which the culture minister responded, “Somebody at your embassy must have some.”24 When the ambassador arrived at the Cour Carrée with a silver vial allegedly containing water from the sacred river in the country where Le Corbusier had made his greatest work, the only people who knew it was merely Parisian tap water were the great orator and the Indian ambassador. When Le Corbusier had counseled Jacques Hindermeyer to boycott what the architect knew would be “a masquerade,” he had used the perfect word.

3

When André Malraux was done with his homily, drumrolls began from the honor guard. Delegates from all over the world heaped floral tributes on Le Corbusier’s casket. The man who had always admired soldiers in full uniform would have been pleased with the military parade that followed. Then the crowd, like a flood tide, forced its way past the police barriers and surrounded the stand on which the casket was resting, as if it were their last chance to approach a deity.

The following day, Le Monde reported the details: “Toward midnight the coffin was placed in a hearse which, preceded by motorcycle escort, crossed sleeping Paris along the banks of the Seine.”25 Few in that honor guard would have known that they were passing the tiny attic apartment where Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, a young man just arrived from Switzerland fifty-eight years earlier, had regularly climbed eight flights of stairs. But all knew they were honoring someone who was credited with having changed the look of the world, if not always for the better.

It was a stark contrast to Yvonne’s funeral eight years earlier. The handful of people in the Cour Carrée who were personally close enough to have been there noted the difference. Yvonne, to whom Le Corbusier had by then been married for nearly thirty years and with whom he had lived for the previous decade, had died on the day before the architect’s seventieth birthday. She had scarcely been known to the public at large. Le Corbusier, himself so visible, had always managed to keep his intimate side private.

Some people said Le Corbusier had met Yvonne Gallis in a bordello, a rumor that the salty Mediterranean woman, her deep red lipstick painted in the form of a heart, did little to dispel. When Walter Gropius, the architect who had founded the Bauhaus, and his wife were dining in Le Corbusier’s apartment in the 1930s, Yvonne, after being silent through most of dinner, suddenly asked Gropius, “Have you seen it?” The ambiguous question puzzled Gropius, whose demeanor reflected his military training. She clarified: “Mon cul”—“my ass.”26 Twenty-five years later, when a young messenger boy went to the same apartment to deliver art supplies, she posed the identical question, again with a wink. It was her everyday line.

The architects in Le Corbusier’s office knew that, whatever work was on the master’s agenda, he had to be home by 5:30 p.m. each day for the first pastis of the evening—his first one, anyway.27 When Le Corbusier was traveling, as was often the case, there were strict instructions for his young associates to phone Yvonne regularly and call on her frequently. If one was privileged enough to be invited to dinner, one knew that there were certain rules to follow in Yvonne’s presence. Work, or architecture in any aspect, was forbidden as a topic of conversation. The talk would mainly be gossip—Yvonne would report on the other inhabitants of the building.

A former beauty, Yvonne had begun to look gaunt and dissipated in the 1940s. She used a cane and had a pronounced limp. But among Le Corbusier’s younger cohorts, who during the war generally got nothing more than the slim pickings of the cafeteria at architecture school, Yvonne’s cooking was legend, in particular her spicy aioli and other Mediterranean specialities.28

Insiders knew that her situation was a tragedy that on some level must have torn her husband apart. Besides osteoporosis and gastritis, the primary cause of Yvonne’s health problems in the last years of her life was her severe alcoholism. Le Corbusier had always done his best to keep this problem, as well as her many other maladies and the rages as intense as her joking, secret from his friends. It was the reason he rarely attended openings, even of exhibitions of his own work. For years, Le Corbusier had taken her to the best doctors, but no one could persuade Yvonne to give up the bottle.

Ever since the end of the war, Yvonne had been in the care of Jacques Hindermeyer. By that time, she was already noticeably debilitated. The reason was a complete loss of sensibility in the legs, a by-product of intense alcohol consumption.

When he wasn’t denying or avoiding it, Le Corbusier partially blamed himself. The architect would often discuss the problem with Hindermeyer, the one person in whom he was comfortable confiding. He told the doctor how sorry he was not to have known earlier in the marriage that Yvonne was addicted to pastis. At the beginning, she rarely drank in front of him. She was by nature so funny and gay that he had failed to recognize her symptoms of drunkenness—or so he claimed. Now that he accepted that she was suffering from something other than the sort of nervous disorder that might be remedied by the right vitamin regime or another of the many solutions he had proffered when he thought there was hope, all that he tried to do was take care of her as best he could.

On one occasion in the midfifties when Le Corbusier went to Baghdad for work and needed to go next to Chandigarh, he returned to Paris first. Hindermeyer asked him why he had not gone straight from Iraq to India. Le Corbusier replied that he could keep only one project in his head at a time and had to return to the office in between. Hindermeyer knew this was a cover-up; the truth was that Le Corbusier hated to leave Yvonne alone for long periods of time and always felt he had to look in on her. To the doctor, “his love for his wife, and his tenderness,” were unlike anything he had ever seen.

Yvonne, late 1920s

Sketch of a femur by Le Corbusier

Yvonne by that time was so unhappy about the way she looked that she kept the apartment dark. “It was horrible for a man who had searched for sunlight his whole life to live in the dark,” his doctor observed.29 Then Yvonne developed a cancer of the anus. Hindermeyer proposed that she see a specialist who could treat her with radium. When the specialist told her to remove her clothes, she delivered a revised version of her famous line, but with none of the old coquetry. “You want me to show the world my ass?” she asked in a rage.30

Yvonne often shouted obscenities and abused and humiliated her husband in front of anyone who happened to be present. Whatever toll he was paying inside, Le Corbusier responded to her wrath by smiling benevolently and caring for her patiently. At one point, Hindermeyer asked Le Corbusier why he never protested when Yvonne said insane things. He told the doctor, “I think only of my happy memories of our youth.”31

THE DAY YVONNE DIED, Le Corbusier had his wife’s emaciated corpse brought home from the clinic and placed in a small room on the upper floor of the apartment. When Charlotte Perriand, his collaborator of many years, came to call, he took her to see it. “Look how lovely she is,” he said to his horrified visitor.32 He was convinced that Yvonne had the purest heart of anyone he knew.

Yvonne’s modest rites took place in the crematorium of the prestigious Père Lachaise cemetery, on the other side of Paris from the apartment. Entering the august cemetery grounds, on their verdant hilltop overlooking the city, and following the road upward to the section for those whose bodies would be turned to ashes, Le Corbusier took in the eerie rows of temple-like stone mausoleums at the burying place of some of the most powerful families in France, as well as of Balzac and Proust and Oscar Wilde. His eye appraised the weighty pediments and ornate carving intended to house the dead for eternity. The crematorium chapel itself was everything Le Corbusier loathed in a building: a ponderous compendium of ill-matched historical references, with a scale that bore no relationship to actual human beings. Only the rows of pines and the deciduous trees, whose leaves were showing the first tinge and withering of autumn, offered some connection with what he knew to be the reality and poetry of life.

Just as Yvonne’s body slid from public view to be incinerated, Le Corbusier rose from the front row of the small chapel. Strong and fit, impeccably dressed in one of his well-tailored dark suits, he bolted forward and disappeared behind the curtain in front of the room. A moment later, the bereaved husband returned, holding a cone of newspaper. “This is all I have left of my dear Yvonne,” Le Corbusier exclaimed to Denise René, his long-time friend and gallerist, and Perriand. He had one of Yvonne’s bones in the rolled-up paper. Among his wife’s ashes, he had found “a tiny cervical vertebra” that was perfectly intact. Cremation in that period was not as thorough as it is now, and this bone, from the top of the neck, had remained.33 René and Perriand gripped one another’s hands in terror. “It was a hellish business, perfectly dreadful,” according to René, on whom the scene made such a gruesome impression that years later she maintained with absolute conviction that the bone had been one of Yvonne’s femurs.34

Le Corbusier walked among the assembled group displaying this remainder of his wife. He continued to clutch it as he followed the urn containing Yvonne’s ashes. The vertebra had a gruesome truth to it that was totally lacking in the monumental neo-Classical and Renaissance-revival style of every surface and object in these oppressive surroundings. The architect took the bone back to his apartment on the rue Nungesser-et-Coli.35 For the rest of his life, he kept it in his pants pocket, like a talisman, occasionally placing it on his drafting table when he was working.

“HE WAS A MAN who loved reality,” observed Jacques Hindermeyer, who often saw Le Corbusier touching the small vertebra. Clinging to his relic, he was rooting himself in a kernel of his wife’s existence, with which he could counteract the vagaries of his feelings.

Le Corbusier’s own bones became relics as well. The day after the public ceremony in La Cour Carrée, the architect’s body was also cremated at Père Lachaise. Deliberately echoing what Le Corbusier had done following Yvonne’s death, his older brother, Albert, the only surviving blood relative, gathered up some of the bone fragments and distributed them. Robert Rebutato’s father, Albert himself, and other intimates always prized their small Plexiglas boxes of Le Corbusier’s remains. They were honored to possess the physical reality of someone whose personality and emotional character were so much harder to grasp.

4

The man whose coffin stood before the mob in La Cour Carrée had been preoccupied by death throughout his adult life. Le Corbusier viewed mortality as an integral part of the grand scheme of human existence, like the skulls that sit amid ripe lemons and velvety flowers in Cézanne’s still lifes. When the mother of one of the most important architects in Le Corbusier’s office, André Wogenscky, died, Le Corbusier had written a condolence letter that treated death as the key element of a building plan: “Death is the exit for each of us. I can’t see why it should be regarded as cruel and hideous. It is the horizontal of the vertical: complementary and natural.”36

Le Corbusier was forty years old when his father died at age seventy-one. He remarked at the time, “I’m well aware now that one is born, grows up, creates, and dies. I am past the growing season. Beside Pierre [his cousin], who is dancing through his thirties, I’m already an old man, a producer certainly, though for some already a hoary traditionalist. One shinnies up one’s trajectory until—when?—it falls back to Earth?”37

On the Monday morning the week after his father’s death at La Chauxde-Fonds, the mountain town where Le Corbusier had grown up, he wrote to his mother, “I often think of dear papa’s serene death, that winter Sunday so full of sunlight and so magnificently solemn. How pure papa’s image remains—so correct, so attached to things of the spirit. He always fixed his eyes on the horizon of an ideal, chimerical country.”38 Georges Jeanneret, an enameler of watch faces, had been a practical man, skillful of hand, but at the end he was above all a poet and spiritual voyager who had found tranquility.

Another week after his father’s death, Le Corbusier wrote his mother again, this time about the death of one of his and Yvonne’s two pet parakeets: “Saturday. Yesterday we found Pilette lying quite peacefully in the middle of the nest. Pitou had been chirping for a whole day, terrified by this emptiness. Believe me, the death of a little bird has something quite mournful about it, awaking ideas related to other deaths, and the coldness of the little bird’s head was the same as the coldness of our dear Papa’s forehead.”39

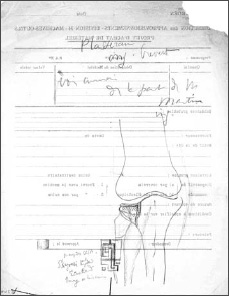

ON JANUARY 11, 1926, at 4:00 a.m., Le Corbusier made a drawing of his stone-cold father annotated in the manner of a death certificate. The open mouth and closed eyes on the gaunt head are almost unbearable to look at.

Drawing of Georges-Edouard Jeanneret made on the night he died. The caption reads: “La nuit de sa mort. 11 janvier 1926 à 4 heures. Sa main gauche était toute gonflée.” {“The night of his death. January 11, 1926, at 4 a.m. His left hand was completely swollen.”}

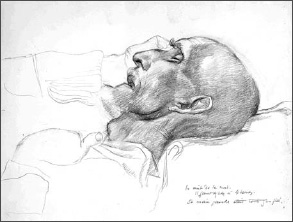

In 1957, he made four drawings of the dead Yvonne. They are like torrid images of the afterlife in a northern Renaissance depiction of the Last Judgment. The bonne vivante who had used lipstick to form her mouth like a movie star’s has no lips whatsoever; she has a lifeless slit sunk within a sharply concave face. Her nose is like the bony beak of a small bird. Her head is wrapped tightly in a bandage that seems to hold it together.

The portrait Le Corbusier drew of his mother on February 15, 1960, just after she died at the age of ninety-nine and to which he attached a lock of her hair, is, if possible, even more horrific. The old woman’s head is thrown back as if it had snapped at the neck. Her tiny pointed chin juts forward. Le Corbusier did not dissemble about the ultimate destiny of the woman whose youthfulness he had exalted only a few days earlier. The truth had to be met squarely.