II

1

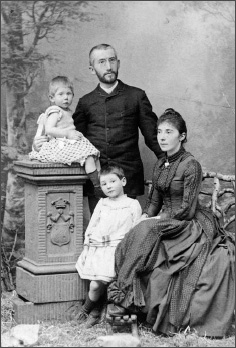

Georges Edouard Jeanneret-Gris and Marie Charlotte Amélie Perret—both Swiss Calvinists, both natives of La Chaux-de-Fonds, a center of the watchmaking industry high in the Alps—were married in 1883. Their first son, Jacques-Henri Albert, was born February 6, 1886. Charles-Edouard came along twenty months later, on October 6, 1887. Marie was then twenty-seven, Georges thirty-two.

Jeanneret-Gris’s meticulous journal reported that, once his wife’s “labor pains announced the imminent arrival of the expected child,” he “went back to work.” The doctor “anticipated the birth would be at 9 o’clock in the evening. As 9 sounded, the child was there…. All went well, he was put immediately on cows’ milk and he drinks his bottle like a man.”1

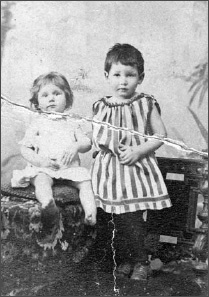

Some five years later, Marie miscarried; she bore no further children. The mother and father and two boys were a close-knit unit. Their disputes as well as the siblings’ rivalry were often intense, but the importance of the core family to each of its members never wavered.

The family lived at 38 rue de la Serre, a few blocks from the main thoroughfare of La Chaux-de-Fonds. It was an unprepossessing apartment in a nondescript five-story structure of reddish-brown stone, pressed against similarly monotonous buildings. The city, in spite of its location, had no Alpine charm. Relentlessly grim, it was composed on a regular grid, with street after street of blank-faced building facades climbing its tedious slopes. Having been destroyed by a fire in 1794, La Chaux-de-Fonds was rebuilt in the nineteenth century in a taciturn architectural style. Laid out as if with a watchmaker’s tools, its sad and weighty rows of shops and apartment houses had none of the magic or complexity of clockworks, only their precision and insistent order. In 1910, when he was twenty-three years old and imagining his return to his natal city while working in Berlin, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret wrote William Ritter, “La Chaux-de-Fonds is indeed a leprous place. You found the right term for this incoherent agglomeration of eyesores. Yet through it blows a wind of living idealism which is quite remarkable and fills you with hope…. Since the old farms of the 18th century, there has been no art tradition.”2 The next year, having returned home, he told Ritter, “But I feel I’m a stranger here, and I still can’t get it through my head that I would always feel that way.”3 On the back side of an envelope, he noted his birthplace as “La Chaux-de-Fonds of shit.”4 After another year had passed, he wrote Ritter: “I’ve already told you how agonizing I find the notion of ending my days here.”5

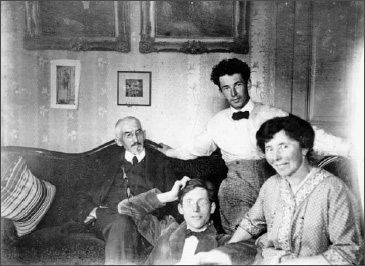

Charles-Edouard Jeanneret (on pedestal) with his family, taken two months after his second birthday (December 1889)

Later in his life as his own propaganda machine, Le Corbusier insistently presented his birthplace as a rich wellspring. Determined that his youth and education be seen as a progression of successes in a well-organized milieu, he summarized a childhood in which he took to the mountains to study the workings of nature, applied pencil and watercolor to paper with the genius of a prodigy, and acquired the education necessary to make buildings and plan cities of unprecedented harmoniousness. He let it be known that his father instructed him about plant life and birds and led him on rigorous hikes, and that his mother taught him music. But he carefully cast aside his Swissness.

When World War II was raging and Le Corbusier had spare time because of a lull in his practice, he collaborated with Maximilien Gauthier on a mid-career biography, Le Corbusier; or, Architecture in the Service of Mankind.6 Hitler had given unprecedented significance to national identity and genetic heritage, an emphasis supported by France’s leadership in Vichy. While the first sentence of Gauthier’s book gives Charles-Edouard Jeanneret’s place of birth as La Chaux-de-Fonds, it leaves out that this is in Switzerland, while stating that Le Corbusier was “naturalized French in 1930, or rather reintegrated within French nationality.”7 In 1964, in Corbusier Himself, the architect amplifies his French roots. He explains that in about 1350, the French of the north massacred the French of the south because the southerners held libertarian ideas about various points of religious doctrine; some of these southern rebels fled to the mountains of Neuchâtel, then primarily inhabited by wolves. Le Corbusier’s ancestors were among the French rebels. “Why these indications of origins?” asks the book. “In a spirit of honesty, to help others understand the rationale of the movement of ideas. Le Corbusier is not ‘Schweiz.’”8

2

As long as the name of the country could be skirted, Le Corbusier emphasized that he came from a mountain paradise inhabited by strong individuals. Three wooden farmhouses built by his ancestors and still called “Les Jeanneret” embodied that fine tradition. As a boy, Charles-Edouard often opted to stay in these rugged dwellings rather than his parents’ apartment. Dated 1626, they bore the family’s name and coat of arms. The future architect credited his distinguished ancestors with having brought to the high Jura region the “style languedocian” they had known in southern France. It showed up especially in the overpowering sloped roofs of these chalets. Their disproportionate scale and profound pitch—they resembled giant, wide-brimmed hats—served effectively to shed snow and assure warmth inside.

The three farmhouses were destroyed by fire in 1910, but Le Corbusier often voiced pride in the role of his relatives in developing such splendid domestic architecture. He also emphasized, in various statements and texts, that the Jeannerets in Languedoc descended from the Albigenses—those Cathars who came from the south of France, primarily the Languedoc and Provence. The Cathars were a heretic religious sect who demanded that the pope and the archbishops forsake all worldly riches, and who were therefore vilified by the Catholic Church for six centuries. They favored an austere and humble way of life; the simplicity of their rites eliminated the need for elaborate churches, liturgical vestments, and all manifestations of ceremonial pomp. Le Corbusier was proud to claim them as his spiritual ancestors.

IN A HISTORY of La Chaux-de-Fonds published in 1894, which Le Corbusier kept in his personal library years after he escaped Switzerland and had achieved international importance, he annotated various passages and drew arrows to others.9 He fastened on to every hint of passion and rebellion. In feverish pencil strokes, he called attention to a maternal great-grandfather who had died in prison for his role in the unsuccessful Swiss revolution of 1831. The architect’s paternal grandfather did even better seventeen years later by descending from La Chaux-de-Fonds on foot to help take the château of Neuchâtel. Le Corbusier bragged, “In 1848, the revolution succeeded. My grandfather was one of the leaders…there is nothing to blush for or to hide about bearing this past of freedom, ingenuity, free will, stubbornness, and guts in one’s own blood.”10

The toughness and willpower Le Corbusier acquired from the milieu of his youth were at his core. At an altitude of one thousand meters, La Chauxde-Fonds had a rough climate that taxed all who lived there. In the course of a year, there was an average of only five hours of sunshine a day; 173 days had some form of precipitation, 65 of them with snow. One learned to endure. For all the misery Le Corbusier would suffer as an architect, he had the strength to withstand the most challenging conditions. Nothing ever prevented him from taking the next step—even if it was toward his own death.

3

Charles-Edouard Jeanneret’s education at home and school emphasized solitude and observation. Drudgery was prized; so was the search for higher spiritual truths. The motto of the Jeanneret-Gris family was

Though silver I possess and gold,

Convinced that this life is a fever,

To my God and his Heaven I pray

The whole thing will last forever.11

Le Corbusier remained faithful to his ancestors’ skepticism about the value of money and focus on that universal timeless sky that precedes and outlives us all.

He also took pride in the qualities he felt he inherited from the competent craftsmen, skillful businessmen, and noblemen from whom he descended. Le Corbusier made much of the qualities that endowed him with intrinsic abilities and reflected favorably on his own endeavors. His father and grandfather had been “skillful enamellists of watch-dials and clock-faces,” while his mother’s family included successful merchants.12

Among his few truly prosperous ancestors was a Monsieur Lecorbesier, a Belgian wed to a Spaniard, whose daughter, Caroline Marie Josephine Lecorbesier, married Louis Perret, a Swiss seller of bed linens who lived in Brussels. M. Lecorbesier’s portrait had been painted by Victor Darjou, a court painter of the Empress Eugénie’s. That cachet inspired Charles-Edouard Jeanneret ultimately to give himself a variation of the man’s name.

Le Corbusier also let it be known that Marie de Nemours “has accorded patents of nobility to Jonas Jeanneret,” while another branch of the family was “confirmed in its nobility by Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia.”13 He did not value anyone more or less because of family background—he married the daughter of a gardener and a flower seller—but he gladly stressed his ancestors’ prestige in the belief that any sort of connection with the people who ran the world might help him achieve his goal of making invigorating architecture for all humankind.

Edouard, age three, and Albert, five (1890)

4

The meaninglessness of artistic phenomena obsessed the minds of our fathers.

—LE CORBUSIER, The Decorative Art of Today, 1925

The prosperous merchants, titled noblemen, religious heretics, and political radicals in the family’s past had little to do with the reality of life in the three small, cluttered, overstuffed apartments in which Charles-Edouard Jeanneret’s family lived during the future architect’s first fifteen years.

Georges Jeanneret-Gris was a competent craftsman, clear thinker, and true devotee of the great outdoors. Marie was sufficiently talented at the piano to teach it. They both esteemed artistry and diligence. But they were above all hardworking middle-class people who had no interest in budging from the society they knew or in transforming it. We can find hints of what seeded Le Corbusier’s mind, but he was one of those rare people whose fire and genius developed inexplicably. How did he emerge from a morose and stultifying milieu with the lust to reshape the world, a generous instinct to improve all human lives, and the creativity to take color and form in unprecedented directions?

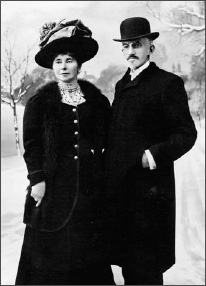

Marie Charlotte and Georges-Edouard Jeanneret, ca. 1900

Marie Jeanneret, who ran the household competently, often repeated the motto of the Gallet family (her mother’s side): “What you do—do.”14 Never procrastinate, even for a second. Although the message eluded Albert, Le Corbusier periodically reminded his mother that these words were his constant gospel. Georges embodied that same principle of concentrated labor. He worked long, hard days, enameling watchcases, writing in his diary with the same order and discipline he applied to his profession. He was so frugal that he recorded the slightest fluctuation in cheese prices in his daily journal. His only break from routine came on weekends when he headed off mountaineering with the Alpine Adventurers’ Club, or took day trips and summer vacations when he led his family on hikes.

Albert and Edouard spent their free time practicing music or drawing or reading. Birthdays and holidays were celebrated as orderly rites.

Jeanneret-Gris’s unmarried older sister, the very pious “Tante Pauline,” lived with the family of four, making the ambience all the more sober. She credited God for everything that happened in people’s lives. But the solitary spinster offered rare playfulness as well, teasing the boys with nicknames they relished. Edouard was delighted with the terms that likened him and Albert to characters from Rabelais. To be a “braggart,” “slattern,” “saber rattler,” “boaster,” “rogue,” “dandy,” “runt,” or “loser” certainly beat being anyone’s idea of an angel.15

FROM THE TIME Edouard was six until he was nineteen, the family lived in a fifth-floor attic apartment at 46 rue Léopold-Robert. The street’s only charm was its name, which was for an early-nineteenth-century painter, Louis-Léopold Robert, who had demonstrated the possibilities of leaving La Chaux-de-Fonds; Robert became a student of David’s in Paris and gained renown all over Europe for his highly colored mythological scenes. One of the main thoroughfares of the city, the avenue was a divided boulevard that, like a river, ran through the base of the valley in which brick buildings and cross streets had been built, sloping upward from it in both directions. Number 46 was pressed between two other identical structures and did not have much of a garden in the back. The Jeannerets’ windows overlooked their neighbors’ massive rooftops.

Inside, the apartment was comfortable enough, cluttered with the trappings of bourgeois life. A fringed valance hung over the dark and lugubrious draperies that were pulled back by ornate cords with large tassels to frame the living-room windows. Lacey casement material muted whatever sunlight might find its way in. The heavy, carved furniture was stained dark brown. Plants in ornate pots crowded the metronome on top of a flower-patterned cloth on the upright piano. Wall hangings flanked Darjou’s portrait of Marie’s grandfather alongside narrow shelves packed with curios. What was absent was any place to rest the eye.

The only weightless aspect of Charles-Edouard Jeanneret’s childhood was music. The piano was almost constantly being played. Marie gave lessons to her students at it, and, starting at a young age, Albert began practicing intensely. Edouard himself began to play the piano at age seven, although he was not nearly as serious about it as his older brother was. The sound of Mozart, universal, light of foot, may have been the first hint of an alternative to the dreariness of the family’s apartment.

Part of what made Le Corbusier extraordinary is that all that he later designed for himself and others provided what his childhood home lacked: visual lightness, playful rhythms, the proximity to nature. Greenery and the sky would be brought into settings full of whiteness, light, and visual calm that would be the antithesis of that hodgepodge of ornament and antimacassars. Once Le Corbusier took charge, the gloom and clutter of 46 rue Léopold-Robert would be eradicated.

5

Study your Physics well, and you’ll be shown

In not too many pages that your art’s good

Is to follow Nature insofar as it can,

As a pupil emulates his master.

—DANTE, The Inferno, CANTO XI

The young family escaped the dark domestic clutter on their Sunday expeditions to the open spaces and uninterrupted whiteness of the high Alps. On hikes that tested Marie and the boys to the maximum, Georges brought them to ravishing vistas. Shouldering backpacks, the family explored the gorges of the Doubs and ascended to marvelous views of the Tyrol and Mont Blanc.16 The devoted father taught his sons rudimentary facts about flowers, trees, ice, clouds, and other aspects of the natural world. Years afterward, Le Corbusier fondly recalled that these lessons in botany and geology were followed by “calm discourse, more abstract but no less respectfully heeded, for favoring one’s neighbor as well as for justice.”17

In adulthood, once he became an avid painter and designer, Le Corbusier considered knowledge and appreciation of nature to be indispensable. In his 1925 The Decorative Art of Today, he wrote, “I knew flowers inside and out, birds of every shape and color. I understood how a tree grows and why it remains standing, even in the midst of a storm…. My father, moreover, had a passionate love of the mountains and the river which formed our landscape.”18 He discoursed romantically on the process of plant growth: “In slow motion, you have observed the poignant, hasty, irresistible drama of buds which unfold, twist with passion, frenziedly gesture toward the light, a veritable rut of plant life, a mystery hitherto sealed which the impassive eye of the lens and inexorable machinery of time-exposure have revealed.”19 When, after World War II, Le Corbusier developed his concept of the Modulor—an organizing unit for all of architecture—he included in his explanatory text one of the drawings of a young pine tree he had made as a child. Like the Modulor, the well-structured tree offered an antidote to disorder. It embodied regularity, a system of governance, and an organizational scheme with the logic of its patterns; nature was a source of balance and control.

On those Alpine outings, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had felt pure elation: “We were constantly on the peaks; accustomed to the enormous horizon. When the sea of fog stretched to infinity, it was like the real sea (which I had never seen). It was the ultimate spectacle.”20 That attraction to the larger vista later inspired architecture that insists that you know where you are on the planet and guides you to feel the orientation to the sun. Le Corbusier configured the outdoor pulpit at Ronchamp to face the hillside and devised the vast terrace at the Villa Savoye as a command post of the surrounding fields.

Young Edouard watched with fascination when his father went off in climbing clothes to ascend treacherous rock faces on Mont Blanc and sleep in natural enclosures formed by boulders. These rudimentary mountaintop shelters, open to infinity, were lifelong models.

The mundane had its impact as well. Edouard’s grandfather made “dials covered with painted flowers or wisps of golden straw” while his father, “under the buyer’s imperious pressure, found himself obliged to make an entirely new effort: to achieve the impeccable enamels, their background of a perfect whiteness.”21 The need to conform to the latest trend in taste bothered Edouard, but he considered craftsmanship and diligence as vital as the freedom of the Alpine crags. Necessity, skill, and the sense of wonder could all function in tandem.

6

It was, for the most part, a predictable Calvinist childhood, except for one unusual element of Edouard’s early education. When he started school at the end of August 1891, more than a month before his fourth birthday, he attended, as did Albert, a private kindergarten that based its methods on the ideas of the early-nineteenth-century German educator Friedrich Wilhelm August Froebel. Froebel had invented special wooden bricks and balls, as well as prescribed activities, to encourage playfulness and practical knowledge of materials. His objective was for children at this vital moment of their psychological formation to acquire skills and a way of life in harmony with the larger world and with God. Froebel’s methods may be among the origins of the seemingly carefree arrangements of brightly colored forms with which Le Corbusier would invigorate and give spiritual life to his chapels at Ronchamp and La Tourette.

In 1893, after two years at the Froebel kindergarten, Edouard switched to more humdrum learning at the primary school, where he remained for the next six years. His life took on a clockwork order except that it was often interrupted by bouts of sickness. Edouard was of frailer constitution than Albert and notably thinner. Aside from the usual measles and chicken pox, he had long-lasting head colds and chronic coughs. His parents tried to keep these at bay with cod-liver oil, but the health problems persisted throughout Le Corbusier’s life, with his search for cold remedies obsessing him almost as much as his quest for clients.

At Le Corbusier’s beckoning, Maximilien Gauthier wrapped up his description of Edouard’s ten years at primary and high school by saying that the boy was “noted as a hard-working and talented student.”22 These are the exact adjectives that Le Corbusier repeats in the first person in Corbusier Himself. It was not so. When nine-year-old Albert delighted his parents by passing his spring exams with flying colors, Georges Jeanneret-Gris wrote in his journal, “The boy gives us much pleasure. His brother is less conscientious.”23 In spite of such a crippling stutter that made it difficult for even his parents to understand him, Albert was considered the easier brother. At age thirteen, now playing the violin, he publicly performed a Mozart trio with his mother and his music teacher. Jeanneret-Gris reported, “The dear child gives us great pleasure, whether in his musical or his scholarly studies…. His brother is usually a good child, but has a difficult character, susceptible, quick-tempered, and rebellious; at times he gives us reason for anxiety.”24

Initially, Edouard had regularly been one of the top three students in the class, and, like Albert, often ended his school year by taking first prize, but the problems began in secondary school, where he began to slack off in general studies, while doing well in languages and the arts. In this French-speaking school, he succeeded in both German and English; in math, however, he never progressed beyond algebra, where his grade was 41/2 out of a possible 6—or a flat C.

As reported by Gauthier, though, he was diligent with all his schoolwork; beyond that, “after class and on Sundays, his lessons learned and his homework done, he drew passionately for his own pleasure.”25 His family often found him drawing at the dining table in his spare time. Sometimes he copied illustrations from children’s books. Rodolphe Töpffer’s Travels in Zigzag, an 1846 account of a walking trip in Switzerland, was a favorite, imprinting notions that affected his subsequent ideas of urban design. He was also a voracious reader, enthusiastic about Old French and passionate about Rabelais, as well as Cervantes, whom he read in translation.

Regardless, it was Albert who won his parents’ approval for pushing himself hardest. While the fifteen-year-old practiced the violin for up to six hours a day, Edouard disappointed his father by making “much less effort than his brother.”26 Le Corbusier never succeeded in dispelling that impression; for the rest of his mother’s life, whenever she was congratulated on the achievements of her son, she purportedly thought that it was Albert to whom the speaker was referring.

IN THE SPRING OF 1900, when Albert and his mother were playing in the orchestra of a local production of Snow White, Edouard took the role of the gnome Sarcasm. His father, unsettled that his son would voluntarily assume a character trait he disdained, accused Edouard of sending everyone into a tailspin. But the part suited the contrary teenager who had dropped down to the lower half of the class and begun to be absent from school without explanation. His algebra teacher in 1901 reported, “Student careless and negligent” his French teacher complained that he talked in class and dropped things on the floor. In history class, the naughty lad “left his seat in an unwarranted and noisy manner.”27 Required to write a three-page essay on the proper behavior of a student, he made matters worse by failing to do so.

At age thirteen, however, Edouard had started taking courses at the local art school, an establishment founded in the nineteenth century to train engravers who specialized in watch decoration. Then, at age fourteen and a half, he left the traditional secondary school—he would have needed to stay for two more years to graduate—to go to the School of Applied and Industrial Arts, a tuition-free institution funded and run by the local commune. Claiming he wanted to follow his father’s footsteps as a designer and engraver of watchcases, for sixty hours a week he studied engraving, design, and artistic drawing in an Art Nouveau style.

Young Sarcasm, however, quickly deemed the family profession “a useless métier, a wretched and outdated métier…. This was how Charles-Edouard Jeanneret learned quite early that the practice of decoration for decoration’s sake is absurd, and the worker who persists in it may well die of it: a severe lesson not easily forgotten when as a young person one has learned it at one’s own expense…. Moreover, it had never occurred to the boy Jeanneret to be engraving flourishes on watch-cases all his days, all his entire life. Without saying a word, he waited for the first occasion to break his apprentice’s contract.”28 So Le Corbusier later explained, through his mouthpiece Gauthier, his pivotal decision not to emulate his father as expected.

While decoration disgusted him, he was becoming a proficient watercolorist, patiently and systematically recording the visual world before his eyes: chalets, trees, flowers, fields, as well as simple interiors. He regularly hung out his neatly executed watercolors to dry on his mother’s clothesline. In their remarkable legibility and graceful application of color, these gentle responses to the local scenery reflect exceptional discipline and control.

They also reveal the obsession Edouard shared with his father over weather conditions and seasonal change. In 1933, Le Corbusier wrote, “Over civilizations, as over trees and animals, passes the play of seasons…. There is winter when only dead wood is visible…. There is spring when the squat buds break out, where the direction of stems and branches appears, where the explosion is universal, life itself! What movement all of a sudden! How joyous it is.”29 The fluctuation between the darkness of winter and the flush of spring and between dark rainy days and bright sunny ones—evident in his early paintings—was increasingly echoed in his psyche.

7

Into his twenties, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret was so determined to escape his stultifying milieu that he fastened zealously onto individuals who offered hope. The first of these hero figures was Charles L’Eplattenier, who taught at l’Ecole d’Art.

Charles L’Eplattenier, ca. 1905

Born in 1874, the son of Swiss peasants from a village between La Chauxde-Fonds and Neuchâtel, L’Eplattenier demonstrated an alternative to life and death in the world of Swiss watchmakers. Attracted to the visual arts early on, he had taken off first for l’Ecole des Arts Appliqués in Budapest and from there had gone to Paris to study painting, sculpture, and architecture at l’Ecole des Arts Décoratifs and then at l’Ecole des Beaux-Arts. With fourteen-year-old Edouard Jeanneret, he continued the education Georges Jeanneret had begun by teaching that the technical perfection as well as the aesthetic charms of trees, plants, and the larger landscape could be the models of all creativity. In turn, art based on nature could exceed nature itself with certain attributes.

Le Corbusier later wrote, “My master, an excellent teacher, free of all routine, a true man of the forests, made us men of the forests as well…. Mymaster had said, Only nature inspires, nature alone is true and capable of supporting human endeavor.”30 That insight changed him forever. Even in his purest and most rational architecture, Le Corbusier invoked the givens of the universe as the ruling force. He invited the natural world inside and made growth and change central to his design. L’Eplattenier also gave his student the initial push to design buildings. “I had a horror of architecture and of architects,” Le Corbusier later recalled, but “I accepted the verdict and I obeyed; I committed myself to architecture.”31

8

Certain books that L’Eplattenier put in the art-school library took hold of Jeanneret. One was The Grammar of Ornament, a historical anthology of decorative design motifs, written by the Englishman Owen Jones in 1856.32 Jones’s premise was consistent with the beliefs already burgeoning in the young man: “Beauty arises naturally from the law of the growth of each plant. The life-blood—the sap, as it leaves the stem, takes the readiest way of reaching the confines of the surface, however varied that surface might be; the greater the distance it has to travel, or the weight it has to support, the thicker will be its substance.”33 This sense that a physical structure, be it a plant or a building, gains its proportions and skeletal organization in response to the life that occurs within it is at the essence of Le Corbusier’s greatest achievements.

During the long hours he spent exploring Jones’s compendium, Jeanneret’s mind exploded with a new faith in human capability. “The plates in the book paraded past us the pure ornaments which man has created entirely out of his head,” he wrote. “Ah, but it was here that we found, to even greater degree, the natural man, for if nature was omnipresent, man himself was there in his entirety with his faculties of crystallization, his geometric formation. From nature we passed to man. From imitation to creation. This book was beautiful and true, for everything in it was the summary of what had been created, profoundly created: the decoration of savages, Romans, Chinese, Indians, Greeks, Assyrians, Egyptians…. With this book we discovered the problem: man creates an oeuvre capable of affect.”34 Jeanneret was developing his breathtaking receptivity to visible beauty, natural or man-made, in any form and epoch.

At the same time, with L’Eplattenier’s tutelage, he was acquiring an ability to work with the tools of his trade, as well as a steadfastness that was to stay with him forever. Le Corbusier later reflected, “At fifteen, I held the burin in my hand. A tool more than fierce. The tool of the straight path. Impossible to turn right or left. A path of loyalty, of honesty. My watch from La Chaux-de-Fonds is its symbol.” In 1962, after spending two weeks near an oven heated at eight hundred degrees Centigrade to make 110 enamel panels for great entrance doors in Chandigarh, he connected his own standards to the rigors of that early training: “If I call yesterday’s work into question, it is because it had left the right path. That is what the watch signified to me. If difficult problems arise, one must press on in spite of everything, straight ahead on the narrow path. If I am a possible architect today, it is because my training was not that of an architect. I have learned to see, with difficulty sometimes. You know, perhaps, that without the somewhat absurd and antiquated watch I had when I was 15, Le Corbusier would not be what he is so modestly now.”35

JEANNERET ACQUIRED DISCIPLINE and skill, but he was not yet remarkable. A table clock and watchcases he designed and a wooden pencil box he carved at age fifteen, as well as an elaborate silver cane handle that he gave to his father and a wrought-iron gas chandelier for his parents’ dining room, were executed capably but without distinction. At the end of his third year at l’Ecole d’Art, he hammered and embossed a repoussé copper relief, a portrait of Dante, which won the highest prize in the school, but it, too, did not show genius.

Then, when Jeanneret’s fourth year at art school began in April 1904, his father requested that he be exempted from engraving. Georges Jeanneret produced a certificate from a local eye specialist showing that Edouard was suffering from significant difficulties with his vision. The school administration accordingly reduced Edouard’s weekly hours of engraving and had him concentrate instead on interior decoration and furniture design. His physical liability pushed him in the direction of his true vocation.

L’Eplattenier obtained authorization to start a new and independent branch of the school, open exclusively to students in their last year who wanted to specialize in a program of art and decoration geared for architects, painters, sculptors, and jewelry designers. Following a summer when he had six weeks of religious instruction at l’Eglise Protestante Indépendante and his confirmation at the end of August, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret joined “the New Section.” A revolution—within himself and in the local community—was in the making.

9

At the same time that Charles-Edouard was breaking out of the family mold, Georges developed a serious case of pneumonia. It was the beginning of a decline, and he was forced to retire from the Alpine Adventurers’ Club. Now selling his watchcases through Longines, he was often in a rage at the great watch company with its cumbersome and demanding administration. Georges fumed, “Little by little I retire from civic life in order to become more and more cloistered and ignored. Will I soon disappear completely!”36 Struck by his father’s glumness, intense worries about money, and struggle to validate himself, Edouard became all the more determined not to take the same path.

Within a year, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret was, without any official credentials, practicing architecture. In 1905, the seventeen-year-old designed his first building. Construction began in the spring of 1906 and took two years. Commissioned for l’Ecole d’Art and called the Villa Fallet, it was on the outskirts of La Chaux-de-Fonds.

In later life, Le Corbusier often boasted that he had designed his first building at that young age, while declaring, “The house itself is probably dreadful.”37 In fact, the Villa Fallet has an impressive energy. Naturalistic ornament animates its surface with an abandon and spirit absent in the other houses of La Chaux-de-Fonds. The house is distinguished by its young designer’s instinct to impart movement and by his drive toward organic form. A happier structure than its neighbors, it enjoys a rare liaison with its bucolic surroundings. Unlike most of the turgid, weighty domestic architecture of La Chaux-de-Fonds, the inventive form of the Villa Fallet resembles the chalets that dot the nearby countryside, and its surfaces echo the local trees and indigenous plant life. Vividly colored leaves and stems adorn the exterior walls. Inside, Jeanneret used three different blends of mortar to create lively murals in the salon and dining room, depicting the flora and fauna of the Jura.

The columns that support the pediment of the roof of the Villa Fallet are topped with edgy, geometric capitals that are variations of cubes. Sharply angled, with bold flat surfaces, these capitals betray an unexpected dash of modernism. In their stark whiteness and rhythmic charge, they are like a sudden explosion into free verse on the part of a young poet who until this moment has adhered diligently to the expected traditions of his trade. Breaking the rules, he had invented something new and exuberant.

Jeanneret gleaned essential lessons for his future from the work on the Villa Fallet. He came to recognize that two important elements in any building project are the materials and the workers who handle them. He also realized that, obvious though the point seems, the plan and its execution determine the success or failure of a project. Seeing the Villa Fallet come to life, he developed a terror of traditional teaching and formulas, while feeling a faith in his own on-the-spot judgment. He knew he must listen more to stone and mortar and his own instincts than to any rule book of architecture.

10

As he saw it, every moment that he tarried he was cheating the world and the needy ones in it of his favor and assistance.

—CERVANTES, Don Quixote

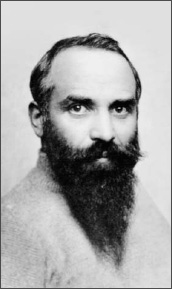

Jeanneret was suffocating amid the tasseled curtains and antimacassars. The hideousness of La Chaux-de-Fonds, he believed, stemmed from an economy centered on mordant mechanization. The systematically processed pettiness of the watchmaking industry penetrated the lives of the local citizenry.

In front, next to his mother, with his father and Albert behind, in the family apartment on the rue Léopold-Robert in La Chaux-de-Fonds, ca. 1905

John Ruskin’s The Seven Lamps of Architecture, another life-changing book for him, justified and soothed his rage at his surroundings and became his torch. Le Corbusier later recalled, “The times were intolerable: it could not last. We were surrounded by a crushing stupid bourgeoisism, drowned in materialism, garlanded with idiotic and machine-made decoration which, without our knowing how to stop it, produced all that pasteboard and cast-iron scroll-work for the delectation of Monsieur Homais. It was of spirituality that Ruskin spoke…. To this swollen mass of the elementary saturations of a dawning machine-age, he offered the testimony of honesty.”38

“The blasphemies of the earth are sounding louder, and its miseries heaped heavier every day,” Ruskin writes.39 But building—and the making of artifacts—might alleviate the pain and replace it with joy. Ruskin opens The Seven Lamps of Architecture with the declaration: “Architecture is the art which so disposes and adorns the edifices raised by man, for whatsoever uses, that the sight of them contributes to his mental health, power, and pleasure.”40

The future Le Corbusier adopted this approach as his gospel and took it in his own direction. There were to be no false skeletons or columns in his work; the pilotis are really the legs of the building, the concrete walls the true body. He was to paint surfaces in vibrant hues or with lively murals but never imitatively; notions like combed graining or imitation marble, however much they dominated the vocabulary of Le Corbusier’s contemporaries, were anathema to him. Ruskin’s candor and frankness, verbal and aesthetic, became his own.

For Ruskin, the most sacred and significant of all the arts was “architecture, [with] her continual influence over the emotions of daily life, and her realism, as opposed to the two sister arts which are by comparison the picturing of stories and of dreams.”41 Jeanneret, accepting the call, knew that his first step was to travel to places where he could be exposed, firsthand, to buildings in all their greatness.

Life at home intensified Edouard’s urge to get away. His parents were being increasingly protective of Albert, who was showing signs of psychosomatic illness. They both pampered and favored their older son by continuing to fund his education while requiring Edouard to pay his own way with his architecture fees. Then, in October 1906, his parents moved to a new apartment, smaller but more modern, at 8 rue Jacob Brandt. Pauline ceased to live with them; the boys no longer had their own spaces. And father and younger son were increasingly at odds. On January 5, 1907, Georges wrote in his journal, “Edouard, all occupied with dancing and with girls, has just bought a pair of skis. He doesn’t appear too healthy, this boy.”42

Inflation was so severe that Georges could not afford to create the white enamel he needed to fulfill many orders from Longines, and he was panicked that his sons might never assume responsibility for themselves. His fear and rage grew all the more intense when, that summer, Edouard declared he was going to Italy. The elder Jeanneret’s only response was: “Voilà—taken from us for one or several years. God be with him!”43